|

ALL THE LAYOUT'S A STAGE

|

|

| |

| Even if you have

never read any of Shakespeare's works you will most

likely have encountered his famous line stating that

"all the world's a stage" (taken from As

You Like It). |

| |

|

|

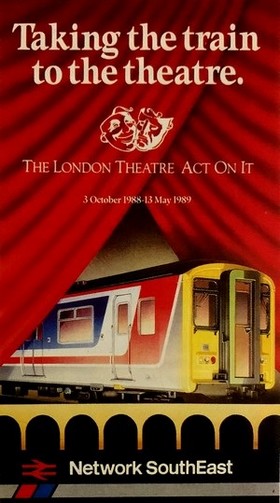

When Network SouthEast, the

British Rail passenger sector mainly

operating commuter trains within Greater

London from 1986 to 1994, launched an

advertising campaign in 1988 showing a

Class 455 electric multiple unit on a

theatrical stage, they probably weren't

thinking of Shakespeare's famous line.

The resulting image does, however,

provide a nice illustration for what

Frank Ellison had stated for model

railways in 1954:

"A

layout is a stage

on which

the buildings and scenery are the

setting,

the

trains are the actors,

and

the operating schedule is the plot."

Ellison

(1887-1964) was an early figurehead of US

model railroading and a prolific writer

of articles in the American modelling

press from the 1930s to the 1950s. He had

spent several years in the theatrical

business and

this experience greatly influenced his

ideas on model railway design, calling it

"theatrical layout design".

The comparisons

and references make sense, not only

because a theatrical production and a

model railway layout both attempt to

"carry out the illusion of

reality", as Ellison put it.

Some of the best

layout design tricks used today are

borrowed from the theatre (such as view

blocks and low relief props) and even

reflect theatrical terminology

("staging tracks"). Ellison

called them "stage tricks for small

layouts", and while they can all be

used as isolated design elements, viewing

and understanding them in the original

context of Frank Ellison's theatrical

layout design opens up a whole new

perspective on how to think of, design,

view and operate a small shunting layout

or shunting puzzle.

|

|

| |

|

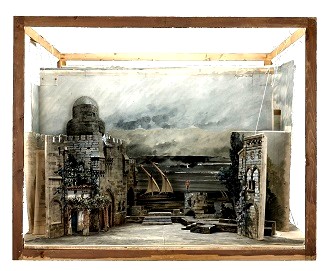

| A

theatrical stage provides a defined space in

which the scene is set and the actors move,

making it the focal point for the audience. The stage design model shown

here (created for an 1895 Paris production of

Verdi's Otello) defines and limits its

"viewing and acting space" inside of

what can basically be seen as a box. Small

layouts often work much the same way: their

"box" is usually more oblong than

square, providing more of a

"cinemascope" view (to borrow an image

from the movies), but provides a defined space

for trains to move in just as a stage does for

actors in a play.

This cube-shaped stage,

introduced during the Italian Renaissance in the

15th century, is still the most

common stage used in the West, with the

"viewing window" generally separated

from the audience by a more or less elaborate

architectural frame called the proscenium

(literally meaning what is "in

front of the scene").

|

|

|

|

| |

| This frame, together with

stage curtains, also conceals the sides of the stage

(called wings), resulting in the familiar setup

which commonly defines what a theatrical stage looks

like. |

| |

|

|

The

example of a modern stage production

shown here also illustrates other

aspects, such as a typically more or less

flat background at the rear of the stage

with additional stage elements placed in

the mid- and foreground. The resulting

forced perspective makes the stage look

much larger than it actually is, adds

depth and interest to the scene, and

allows the actors to enter and exit the

scene more convincingly. More

elaborate settings will feature

foreground viewblocks, half-relief props

and other means to influence the way the

scene is seen (or not seen) by the

audience.

Finally, the lighting

enhances the focal point character of the

stage, with the audience and most of the

proscenium arch in the dark.

|

| |

|

|

| It

isn't difficult to see how Frank Ellison

came to transpose the defining

characteristics of the theatrical stage

and a theatrical production onto model

railway layouts - and even though

shelf-layouts were practically unheard of

in Ellison's days, their similarity to a

stage is so obvious it almost goes

without saying. Some

smaller layouts - especially those

appearing regularly at model railway

exhibitions - even feature an elaborate,

all-around proscenium arch (which often

also hides an integrated lighting

system), although these are more commonly

described as "shadow box"

layouts, with reference to a type of

display case rather than a theatrical

stage. However, theatrical

layout design doesn't require replicating

an actual stage to that extent - "open top"

layouts work just as well.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

SETTING

THE STAGE FOR A MODEL RAILWAY

LAYOUT

|

|

|

|

| |

- The

insight and inspiration to be

gained from comparing a model

railway layout to the theatre

becomes apparent once you think

about "setting the

stage" - which is not about replicating

(providing an exact rendition)

but rather about representing

scenes of the real world

("re-presenting"

certain features while leaving

out others).

|

| |

|

|

This is an especially

helpful approach for

small layouts, where

applying a degree of modeller's

license (taking

certain liberties in

modelling something) is

sometimes the only

feasible way to

"re-present"

real trains (or even just

one's own perception of

what a railway setting

looks like and where and

how trains do what they

do) on a model layout. The

similarities between a

theatrical stage and a

(small) model railway

layout become even more

apparent when looking at

the key functions a stage

is generally designed to

fulfill - almost all of

which immediately ring

several bells when

related to layout design:

|

|

|

| |

|

|

- establish the limits of and define the

"playing space"

- separate "onstage"

from "offstage"

- help define the "place and

time"

- create a "theme" and

"mood"

- direct the

observer's focus and attention by using

- selective compression &

forced

perspective

- low relief

& backscenes

- viewblocks

|

| |

| It's not just about models,

though - quite often real locations and railway settings

provide excellent examples of what can be replicated as

"theatrical stage settings". |

| |

|

LIMITING

AND DEFINING A LAYOUT'S SPACE

|

|

|

|

| |

| In theory,

the world around us is, from our perspective, endless

since we can turn and move around in it and never reach

"the end". However, there are instances where

our movements and therefore also our perception are

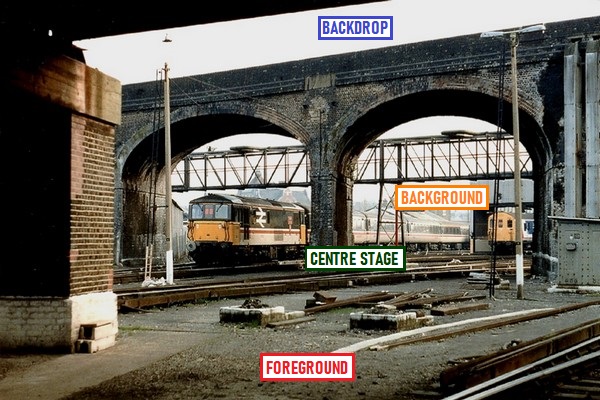

blocked and therefore limited. Take, for example, this

view of Clapham Junction, Britain's busiest railway

station, situated a few miles South of the River Thames |

| |

|

|

The

view of the scene - the "playing

space" - is limited both to

the right and to the left hand side by

architectural features. They block the

view of the photographer and prevent him

from having a clear and sweeping 180

degrees view of the scene. This

is exactly what stage designers do - they

make use of "flats",

drapes, "platforms" and other

means to delineate the areas that will be

used by the actors, and may also employ a

great deal of "masking" so that

actors or objects outside a clearly

marked area cannot be seen by the

audience.

There is also a distinct

segmentation of the depth of what the

onlooker is seeing: there is foreground,

a "centre stage", a background,

and a somewhat indistinct backdrop.

Differences in lighting enhance this

perception.

|

|

|

| |

| This is

exactly how most stage designs function in the theatrical

world, and most model railway layouts employ the same

techniques of structuring spatial depth, width and height

one way or another - simply because we all model in three

dimensions. |

| |

| However,

if applied systematically, the theatrical

stage concept can provide additional

effects for a layout, and one such stage effect which

can easily be replicated on a model

layout is to enhance the feeling of depth

by placing one or several items in the

foreground. As this example from the

prototype illustrates, it doesn't take

much: a pair of axles with wheels set out

in front of a track instantly sets the

Class 08 shunter back a little bit in

this scene at London's Old Oak Common

depot in the late 1980s.

The same effect can be

achieved on a layout without using up a

lot of actual space by using anything

from shrubbery to a car to any sorts of

appliances.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

SEPARATING

ONSTAGE

FROM OFFSTAGE

|

|

|

|

| |

| Also no stranger to railway

modellers is the concept of "onstage"

(usually the scenicked visible part of a layout) and

"offstage" (an imagined connection of

the layout to "the rest of the rail system"). |

| |

| The

latter may or may not exist as an actual

part of the layout (such as a fiddle

yard), but the transition from

"onstage" to

"offstage" is commonly hidden

by a "viewblock". Favourite

choices are tunnels and bridges, and an

actual (and from a modeller's perspective

very convenient) such example found on

the prototype is shown here. Upper

Sydenham station was the

penultimate station on the London Chatham &

Dover Railway's route to Crystal

Palace. Due to the topography of the

area, it was situated - somewhat unusual

for a suburban station - between two

tunnels set very closely together:

Crescent Wood Tunnel (seen here) and

Paxton Tunnel, only a quarter of a mile

down the line (the latter taking the

branchline south into Crystal Palace High

Level station).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The line closed in 1954 due to

more convenient rail connections in the immediate

vicinity, but the fact that there was not only a tunnel

portal opening up right onto the station platforms but

also a footbridge crossing the tracks right in front of

it makes it a prime prototype example of a "hidden

transition": from the viewpoint of a passenger

waiting on the platform, trains would either appear

"onstage" from the tunnel or disappear

"offstage" through it. Again, this is

exactly how most stage designs function, although the

tunnel/bridge feature is a typical model railway layout

solution to hiding the transition from onstage to

offstage. In a theatre, many different means are used to

accomplish this, depending on the play and stage setting,

but they can all be described as "viewblocks":

the audience is supposed to see a logical and smooth

transition, not the actual exit off the stage, as this

would destroy some of the effect the stage layout is

trying to create.

From a theatrical layout design

perspective this means that you want to plan ahead to

incorporate appropriate view blockers into the design

before actually building the layout.

"Appropriate" is defined by the next major

function a theatrical stage has.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

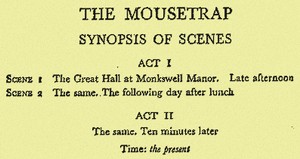

| Defining the where and when for

the audience is such an important element for theatrical

plays that they have included this information in their

scripts (and later programme booklets) for centuries. |

| |

|

|

Take,

for example, one of the longest running

plays on record, Agatha Christie's famous

Mousetrap. The "synopsis of

scenes" not only spells out where

and when the events take place, but also

details their chronological order. Other plays will be not

quite as specific, but still attempt to

clearly define the place and time

of events depicted on stage. Few

plays, books or movies fail to do so (and

if they do, it is often a deliberate

move) because it creates coherence and

therefore a "believable illusion of

reality" - something which would be

immediately upset if a group of cavemen

were to enter the stage during the Mousetrap.

|

| |

|

|

| It doesn't

mean that all details need to be perfectly spot on (not

everybody watching a movie set in the late 1960s will

notice a certain car being an early 1970s model) but

glaring anachronisms (such as a 1970s inspector whipping

out a smartphone) will be noticed. And when an audience

is struck by something as being "off", the

illusion of reality is at least momentarily destroyed.

Unless intentional, it is definitely something theatrical

productions put a lot of effort into avoiding (e.g. by

paying attention to correct props and clothing). |

| |

| This is why few railway

modellers will want to replicate the

scene depicted on the cover of the 2020

Hornby catalogue. The amount of

coherence deemed necessary or desirable

for a specific model railway layout will

always be a matter of choice and

ultimately commitment. From a theatrical

layout design perspective, the point to

take away here simply is that defining

place and time and ensuring that the

stage settings reflect these is essential

to creating something that feels

"right".

It is important to

note that coherence doesn't equal a

static and inflexible approach - even the

very detailed settings for the Mousetrap

contain a shift in time (one day only,

but some plays cover several years or

even decades) and a very general temporal

setting of "the present" (which

could also be "the 1980s" or

"steam to diesel transition

period"). A more cohesive approach

to designing, detailing and running a

layout in no way precludes the liberty of

doing things according to personal

preferences, and "modeller's

licence" can easily explain steam

and diesel locomotives running side by

side if assuming a "heritage

railway" setting. If this is done

coherently, it will also be convincing.

Creating

cohesiveness the way a theatrical

production does can actually also be a

helpful tool if you tthink about what can

be done with the right props.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

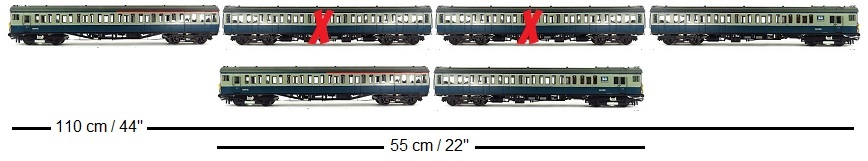

| Imagine a layout featuring a

passenger station set within the sprawling network of

railway lines criss-crossing England's South East. How

can one single layout be set up to coherently represent

the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and even early 1990s? |

| |

|

|

In setting the stage,

some elements can remain unchanged such

as the station building, as many of them

weren't modernized in real life during

those periods. As for props, changing

certain items out depending on which

period is to be represented will go a

long way in creating cohesiveness. In our

case, station signs (which changed

significantly between the 1960s and the

1990s) will have a major impact for

audiences in the know. The actors in this

example can remain the same (third rail

Electric Multiple Units) and will simply

require to sport the correct costumes

(i.e. livery) for the period displayed. Planning ahead for

this and making some prominent props

(such as vehicules and platform details)

exchangeable will actually provide the

layout in question with a simple way of

providing a very believable swap of

period markers.

|

| |

|

|

| This is just one example of how theatrical layout design can

provide additional interest in a layout by using props

and settings accordingly. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| A cohesive overall

"feel" for any stage production can further be

enhanced by creating a clear sense of theme and mood. |

| |

| Taking

the railway scene shown here it will be

evident to anyone that the setting is an

urban one (as opposed to e.g. a rural

backwater). The location is indeed a

London terminus (Cannon Street), and the

trains in view suggest a theme of

"commuter trains". Some details visible

(such as the electrified third rail)

enhance this perception even more, even

though they may be lost on a majority of

people looking at this snapshot - the

important thing is that, again, it is all

coherent and "right" to support

a theme of urban

passenger trains.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| As far as mood

is concerned, this view of the platforms at Cannon Street

indicates a somewhat slower moment (as opposed to the

rush hour) during the day (as opposed to nighttime), and

the overall impression is of a certain degree of order

and cleanliness (the year is 1979, and although there was

plenty of littering (not as prominently visible here)

graffiti was still rare). It's a fairly proper looking

station. |

| |

|

|

Themes

and moods don't necessarily need to be

very clear cut and can leave quite a bit

of room for interpretation without

becoming ineffective. In the scene shown

here, the only "messages"

conveyed are that the location is a rural

spot somewhere in the US (inspite of the

Union Pacific locomotive, the place is

Markham, Virginia), the season must be

autumn or winter, and we're looking at a

freight train. In

comparison to the Cannon Street scene

there a fewer clues as to theme and mood,

but they still project a coherent overall

impression. In exactly the same way, not

all model railway layouts will need

"high definition" themes and

moods, but it is a useful concept to bear

in mind, especially if the purpose of a

layout is to capture a certain era, area

and/or type of operation.

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

USING

STAGE TRICKS FOR A MODEL RAILWAY

LAYOUT

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| A major topic for

Frank Ellison was the use of "stage tricks" for

small layouts. They are all essential tools for

theatrical productions, and it is a credit to Ellison's

influential writing in the model railroad press in the

1950s that most if not all of these "tricks"

have become common modeller's knowledge, even though the

name Frank Ellison will most likely be unknown to most. |

| |

| |

SELECTIVE COMPRESSION

|

| |

| In essence, there is no reduced scale modelling

without selective compression. Even O scale models -

which are considered "big" in most railway

modelling quarters - simply can't replicate every element

of the real thing when shrunk by a 1:43 ratio, and that

physical necessity for compromise grows as the models

shrink even further. In having to thus compress a model,

manufacturers will do so selectively, trying to retain

the salient features and characteristics. The same

necessity applies to layouts. Even the smallest branch

line locations are far too spacious to be modelled

without any compression at all, a point well illustrated

by Angela Halliday and Tony Caine's

Hayling Island, a dimensionally accurate 4mm

finescale model of a small branch line terminus in

South-East England in the 1950. This layout required a length of 20 ft (6 m)

and a depth of 7 ft (2,10 m) in order to model what is

essentially a fairly small affair as railway locations

go.

There's

simply no way around selective compression, but the

theatrical layout design perspective offers a few

additional takes on the subject. On a stage,

selective compression is very often achieved by spot

lighting, and while not

really practical for modellers, the point to take away

from this is that clever accentuation on a layout, e.g.

through foreground or background placement of certain

props (think buildings and scenery) can direct (and

potentially "fool") the viewer's perception of

what he is seeing. Selective compression also applies to

the actors, i.e. the trains. If platforms and sidings

need length shaved off, then shortening trains will

render the scene visibly more realistic. This can either

be achieved by selecting a period of time when shorter

rolling stock was the norm, or by shortening train

formations. It's always a compromise, but it can be made

to look coherent; in fact in some cases, manufacturers

already make that choice for the modeller. One of many

examples is Bachmann's OO model of an EPB electric

multiple unit, which is only offered as a two car model

(2EPB) but not as a four car unit (4EPB). Both are

prototypical, but the shorter unit obviously affords the

modeller with more flexibility and can be considered a

form of "ready to run" selective compression.

Selective compression is also

applied to time, often without giving this much thought,

since few modellers will want to sit around for two hours

in order to run the next train in an "uncompressed

time frame". The solution is to either run a

sequence of train moves (possibly even based on a

timetable) to a "fast clock" (where one actual

minute may represent e.g. 15 minutes) or simply start the

next move once the previous one has been completed.

|

| |

| |

FORCED PERSPECTIVE

|

| |

| Forced perspective is a technique

which essentially employs an optical illusion in order to

make an object appear farther away, closer, larger or

smaller than it actually is. It works by manipulating our

visual perception and tricking our brain into making

false assumptions on how objects correlate in terms of

size and distance. |

| |

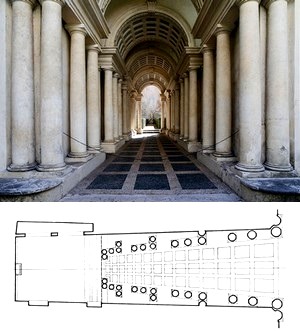

| The

technique has its origins in

architecture, with one of the most famous

examples being a gallery at the

Palazzo Spada in Rome. Designed in 1632

by Francesco Borromini, it gives the

illusion of being around four times its

actual length by cutting down the size of

the pillars at the back and moving them

inwards at the same time. The effect

works because this is how we know

perspective to usually work, but it also

requires the viewer to be fairly static

(in this case cleverly assured by the

foreground pillars) as movement often

destroys the effect - if someone were to

walk into the Palazzo Spada gallery the

trick would be revealed almost

immediately. This is also why the forced

perspectives used in the Lord of the

Rings movies required carefully

calculated and synchronized camera and

set movements. Forced

perspective can work on a layout, but

only if it can be "controlled"

by a restricted viewpoint - which is why

attempts at, for example, adding depth to

an actually shallow background by using

forced perspective, often don't really

work that well. Even the use of N scale

items (including a running train) in the

background of an HO scale layout often

doesn't hold up for more than a few

seconds as full control of the technique

would require it to be viewed at

eye-level only.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Frank Ellison was aware of the

fact that while forced perspective could be made to work

on a theatrical stage, it was not an easily transferable

technique to layout design, quite unlike low relief and

viewblocks. |

| |

| |

LOW RELIEF

|

| |

| The concept of low

"relief" (from Latin relevare,

"to raise up") originates with the sculptural

technique of leaving items attached to a solid background

rather than having them fully modelled and free-standing.

|

| |

|

|

Stage designers for both

the theatre and then movie productions

took up the idea as it allowed them to

only have to show a part of e.g. a building,

which saved both space and money. The

lots of movie studios everywhere quickly

accumulated an abundance of such

"fake buildings", as they were

highly effective in early productions

which featured only very reduced camera

movements. The technique

can at times even allow for ultra shallow

"fronts", as long as the camera

doesn't allow the viewer to "peek

behind the scenes" - which is why

"flats" are also a very common

technique in stage productions.

|

| |

|

|

| The benefit of the space saving

nature of "low relief" buildings has made them

a ubiquitous feature on model railway layouts - and

possibly the most common theatrical layout design feature

not even recognised as such. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

The top left picture shows the

"silent movie effect"- viewed from the

front at a right angle, there is no way of

telling that the warehouse building (a

Scalescenes OO card kit) is actually only a very

flat front. However, moving

the viewpoint sideways just a bit immediately

reveals the flatness of the building (top centre

image), so in order for this to work the

warehouse needs a bit more substance (the kit is

designed as a very low relief, so the roof and

side walls were kit-bashed).

"Flats" can work

on their own, but they need to be right up to the

backscene (as the wall in the image to the left);

combining "low relief" and "ultra

low relief" buildings not only adds more

visual interest, it also reduces the possibility

of the effect not working.

|

|

| |

| For additional effect, scenic

items restricting sideways viewing even more can be

added, such as trees or industrial chimneys. |

| |

|

| |

| Low relief "stage

items" are so versatile because they work both in

the fore- and background, as well as in defining the

points "where the stage ends" - modelling just

the throat of a railway station or a tunnel portal as the

lateral end of a layout or module follows the same

approach of only showing a part of what onlookers expect

to be there "beyond what is visible". |

| |

| Sometimes, several

different components are required to achieve the

illusion of "more than is actually

there". A flat photographic backscene along

with some added semi-relief props can make a

scene look threedimensional and create the

impression that, for example, a road crossing the

tracks actually leads to somewhere in the

background. |

| |

|

|

|

Additional layers of

scenery allow the foreground to blend

with the flat backscene, further enhanced

by some strategic "shadows". As

on a theatrical stage, it is all aimed at

deceiving the onlooker into believing

that the scene has more depth and reaches

further back than it actually does. The scene (which is

only six inches deep) could be left this

way, but in order to fool even a

lingering observer a bit longer, a truck

is added to the scene, acting as a

viewblock while also deflecting attention

from the flat backdrop to an actual

three-dimensional prop in the foreground.

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

| In order to achieve this

illusion, some further theatrical trickery is

necessary - because what seems to be a truck is

actually only part of one. Cutting down the rear

of the vehicule at a 45º angle not only allows a

longer vehicule to be squeezed into what little

space there is, it can then also be placed in a

skewed position (another theatrical trick for

props that are supposed to fool our sense of

perspective). |

|

| |

| |

BACKSCENES

|

| |

| As theatrical stages developed

into the type of setting we know today, concepts of how

to convey a certain location started to form, and this

attention was also directed towards the rear of the

stage. A solution which proved to be both straightforward

and versatile was to simply hang one or several painted

curtains at the back of the stage to indicate scenery. |

| |

|

|

Often used in

combination with the side wings,

the function of a backdrop (as

it came to be called in US theatrical

jargon since the 1880s) is illustrated by

this elevated view of the stage of Marie

Antoinette's very own theatre

at Versailles Palace in Paris. Backdrops quickly

became an important element of stage

design, but were generally fashioned to

be rather generic representations of

"a forest", "a city

street", or "inside a

house" - which made it possible to

use the same backdrop in any number of

different plays. At the same time, no

attempt was made at providing a highly

realistic rendition of whatever was

depicted; after all, the name itself

implied that it was at the very back and

should therefore not deflect the

audience's attention from what was going

on elsewhere on the stage .

|

| |

|

|

| In the context of model

railroading, the backdrop became the background scene,

which was then contracted to backscene. A selection of such backscenes for

layouts became widely available as of the 1960s - and

most are still offered today. |

| |

| They

all work very much like the classic

theatrical backdrop (as can be seen from

this classic Walthers "Instant

Horizons" city backscene) in that

they are clearly paintings and not

(photo)realistic renditions. Commonly

printed on a roll of paper (the example

shown here measuring 24"x36" /

60cm x 90cm), both Walthers and Peco

still offer a wide variety of different

backscenes which are designed with some

transition space to the sides so they can

even be joined up in multiples.

|

|

|

|

| |

| These backscenes were (and still

are) advertised as an easy way to add depth and distance

between the actual scenery of a layout and its backboard,

but quaint as they may be they have also become dated and

maybe even a bit corny - besides, people get bored of

seeing the same thing over and over on different layouts.

The question of how to design their very own individual

backscene has thus become a central one for many

modellers and is directly linked to the rise in

popularity of small and shelf-style layouts. Accordingly,

there are hundreds (if not thousands) of videos, websites

and blogs dealing with the subject and offering advice. |

| |

|

|

One school of thought aims at

creating highly realistic backdrops, and many

layouts have started using actual photographs,

either as a collage or a large landscape image

(some of the newer commercial backscenes offered

make use of this technique as well, such as those

offered by Gaugemaster in the UK, which feature

generic landscapes with background hills). The ultimate step in logic

with this approach is to just have a backdrop

working as a "blue screen" and then use

an imaging software to add an actual picture - as

Walthers did for their catalogue in advertising

their HO low relief warehouse kit - to create a

virtual backscene (just as theatres now use

projections to enhance their stage design).

|

|

| |

| A very different approach is the "less is

more" school of thought. In essence, this works on

the assumption that a backscene should be as neutral as

possible - almost as though someone was telling the

onlooker that there's nothing to see in the back and to

focus on modelled features of a layout or module. This can easily be achieved by simply

painting the backscene in a neutral and toned-down

colour, and then very lightly adding some variation to

"the sky" but without attempting to actually

render any clouds - a technique applied to the scene

shown here on a Z Scale

(1:220) module. The mood can be changed by simply

going for a different colour; a light or dark grey would

create an atmosphere of a dreary and rainy day or even of

an impending thunderstorm.

|

| |

|

| |

| The important thing with all

types of backscenes is to ensure that there is a smooth

transition between them and the actual layout. In order

to achieve this a mixture of techniques can be used -

which may include another theatrical stage trick:

viewblocks. |

| |

| |

VIEWBLOCKS

|

| |

| This is a layout design trick

which Frank Ellison actually arrived at by turning the

staging technique of "blocking" on its head. In

a theatrical performance it is vitally important that the

audience can see what they need to see in order to follow

the events. The positions (and movements) of actors and

props therefore have to be arranged ("blocked")

with the audience's fixed viewpoint in mind - which, for

example, is why actors rarely turn their back to the

audience while reciting their lines (not even when

addressing someone situated behind them). Ellis realized

that the opposite effect of "blocking" actually

hides things from an audience, simply by putting a

"view block" in their line of sight. It is of

course a phenomenon which can be encountered in real life

time and time again: a road curving out of sight, trees

obstructing a view, even people walking into your

"shot" as you try to take a picture of

something or someone.

|

| |

| In terms of layout design

it offers the possibility to create the

illusion that there is "more"

than can actually be seen. It also

creates the illusion of more depth to a

scene if a viewblock is positioned in the

foreground. Or it can simply hide the

exit to "staging tracks". "JD" signal

cabin at the Chesapeake & Ohio

Railway Museum in Clifton Forge,

Virginia, evidently doesn't hide any non

existing scenery, but it illustrates the

effect a foreground prop can have on a

layout.

The possibilities

are endless, both in urban and

countryside settings (in the Z

Scale example below a few trees

placed in the foreground provide a

slightly restricted view of the tracks,

which immediately adds depth to the

scene).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| Theatrical Layout Design doesn't, of course, have to

be applied rigidly - it works just as well if only bits

and pieces, a stage trick here and a stage setting

concept there, are applied. But taking a step back and

looking at a small (shelf) layout or a shunting puzzle

layout as something akin to a stage in a theatre can

provide some really interesting thoughts and ideas. Frank

Ellison's 1954 book Frank Ellison on Model

Railroading has been out of print for decades now

and will prove difficult to come by, but others took up

his ideas on Theatrical Layout Design, such as John Armstrong in his classic Creative

Layout Design (1978) or Carl Arendt, the late but

undisputed master of the micro layout, on the pages of

his website.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

|