|

|

| |

SHUNTING PUZZLES

|

| |

|

| |

| SHUNTING, as

defined by the Oxford English Dictionary,

primarily describes the act of "pushing or pulling a train or part

of a train from the main line to a siding or from one

line of rails to another: their train had been shunted

into a siding". While this

conforms to British and Australian usage, its equivalent

in North American railway terminology as used by the US

Department of Transportation is SWITCHING.

|

| |

John

Vaughan photograph, (c) Adrian Wymann collection

|

|

Commonly, this is done by

purpose-built shunting locomotives, but in remote

or less frequently visited locations, shunting

duties are performed by the same locomotive used

to haul the train on the mainline. Such is the scene at the

Parkandillack china clay works in Cornwall in

February 1982, where Class 37 135 (a Co-Co

locomotive weighing no less than 102 tons) is

shunting its train, while illustrating at the

same time that shunting almost always involves a

lot of legwork by railway staff.

|

|

| |

| Evidently, the terms shunting

and switching denote the same procedure and are

completely interchangeable; the heading of this page,

SHUNTING

PUZZLES, can

therefore also be read as SWITCHING

PUZZLES. |

| |

| |

My favourite definition

of PUZZLE

actually has a few layers of dust to it, as it

comes from the 1911 edition of the Encyclopedia

Britannica. However, as puzzles aren't new,

it still captures the essence in a miraculously

short sentence:

"PUZZLE: a perplexing question,

particularly a mechanical toy or other device

involving some constructional problem, to be

solved by the exercise of patience or

ingenuity."

Clearly,

this is something real railways and railroads

would like to keep to a minimum in daily

operations. The two concepts are only brought

together voluntarily in the field of railway

modelling (model

railroading) where shunting puzzles

can generally be described as being reasonably

compact layouts which - by way of definition

through their name - have two basic

characteristics:

|

|

|

|

| |

| 1 |

|

First

of all, they are concerned with shunting, meaning

that they are conceived and built to allow

rolling stock to be moved around on an

appropriate track layout with sidings. On its

own, this is simply the definition of a shunting

layout. |

| |

|

|

|

| 2 |

|

Secondly,

this shunting is not done according to

spontaneous decisions of the operator but rather

follows a framework of set rules which create a

shunting order (usually by random selection of

both the cars to be shunted and where they are to

go), i.e. the operator is told what to do. This

deliberately introduces a range of more or less

complex and therefore difficult initial

constellations of the rolling stock which is to

be shunted, and thus creates the challenge of

successfully tackling the given shunting order.

It is this second aspect which is the key element

in turning a shunting layout into a shunting

puzzle. |

|

| |

A third characteristic, although

arguably a matter of taste, is that shunting puzzles

provide the most fun and sustained interest in operating

per square inch of model railway layout ...

|

| |

Shunting in

progress in the sidings at Little Bazeley, a 00 scale UK shunting puzzle

based on Inglenook Sidings

|

| |

It will

probably never be possible to determine where and when a

railway modeller first had the idea to turn a shunting

layout into a shunting puzzle. Most certainly, it was

someone who was looking for ways to make operating the

layout more fun, and probably also someone who liked

playing games. The first example I know of is Alan

Wright's way of operating his Wright Lines layout

in the 1950s, ultimately leading up to his classic Inglenook

Sidings, but there are bound to be earlier

instances. The other "classic" switching puzzle

is the Timesaver, devised by famed US modeller

John Allen in the early 1970s.

The

aim and purpose of this website is to illustrate and

explain how different shunting puzzles work and how best

to build and operate them. Over the years - not the least

thanks to the rise of the internet - many variations and

new types of model railway shunting puzzles have been

conceived and successfully built and operated by a

growing number of increasingly enthusiastic modellers.

However, no matter if you are a complete newcomer to the

subject or a seasoned shunting puzzler, it is always a

good idea to look to the two classic shunting puzzles for

information and inspiration.

All model railway

shunting puzzles generally belong to one of two different

types of puzzles: sequential movement

(where a pre-determined order needs to be formed) and distributional

ordering (where items must be placed where

they belong).

|

| |

DISTRIBUTIONAL

ORDERING

SHUNTING PUZZLE

Solving a distributional ordering

puzzle requires you to distribute individual

elements of a puzzle in such a way that they end

up being in what has been pre-determined as their

correct place.

BEST

KNOWN EXAMPLE:

JOHN

ALLEN'S

TIMESAVER

The

classic and by far the best known shunting

puzzle: John Allen's Timesaver, which was originally presented in the

November 1972 issue of Model Railroader.

|

|

SEQUENTIAL

MOVEMENT

SHUNTING PUZZLE

Solving a sequential movement

puzzle requires you to follow a series of

sequential movements within a set of strict rules

in order to arrive at a predetermined result.

BEST

KNOWN EXAMPLE:

ALAN

WRIGHT'S

INGLENOOK SIDINGS

The

classic British shunting puzzle is Alan Wright's Inglenook Sidings, which originated in 1978 but dates back

to a scheme already used by Alan Wright on his

1950s layout Wright Lines.

|

|

| |

|

| |

SHUNTING PUZZLES ON THE

REAL RAILWAYS?

|

| |

| Are shunting puzzles an aspect of

actual real-world railway operations, or are they

something only to be found in the imaginary world of

model railways? Railway companies

try to run their services as smoothly and as efficiently

as possible, and simple track layouts are one way of

achieving this.

|

| |

John

Vaughan photograph, (c) Adrian Wymann collection

|

|

Model railway shunting puzzles,

on the other hand, deliberately set up

complications, and it is in this approach that

the two worlds of real and model trains differ. However, there are many

locations served by real railways that can

provide quite a bit of head scratching for the

shunting crew. In those cases, the only

difference then lies with the terminology used;

in the real world, it is called a challenge and

not a puzzle, since it's not done for the purpose

of entertainment.

The scene at the

Parkandillack china clay works in Cornwall in

February 1982 illustrates this nicely - in order

to get the required shunting moves done, the

class 37 locomotive even has to sandwich itself

in between two rows of rolling stock.

|

|

| |

| Shunting puzzles thus do indeed

reflect at least some aspects of the reality of actual

railway operations. The chance distribution of rolling

stock (as opposed to logistical requirements dictating

where freight stock goes) could be viewed as artifical,

but then again, as the saying amongst railway modellers

goes, there's a prototype for everything. |

| |

|

| |

A LITTLE BIT OF

SHUNTING PUZZLE THEORY

|

|

| |

| Model

railway shunting puzzles are fun because they give a

sense to running trains by posing a challenge, and

finding the solution to this challenge is both satisfying

and entertaining. In this respect, shunting puzzles are

like any other puzzle. Therefore, in order to take a

"look behind the scene" and see how shunting

puzzles work, it is best to start with the general

question: |

| |

What exactly is a puzzle?

Puzzles come in many forms and styles,

such as riddles, mazes, jigsaws, blocks, rings,

wires, and lots more.

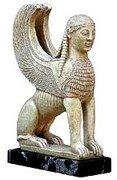

Some of the

oldest "mechanical" puzzles come from

China (perhaps the most familiar being the ch'i

ch'iao t'u or Tangram), while

possibly the best known historic European puzzle

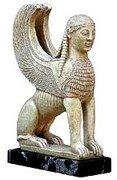

goes back to a tale from Ancient Greece, dating

from 600 BC, and related by Sophocles and

Apollodorus: The famous riddle of the Sphinx

which sat on Mount Phikion

and asked the Thebans "What has one voice,

and is four-footed, two-footed and

three-footed?" Unless travellers gavethe

correct answer (which was "man" - crawling in

his infancy, walking in his prime and using a

stick in old age) they would be killed by the

terrible Sphinx...

The origins of

the word “puzzle“ itself are disputed.

It has been suggested that the verb to puzzle,

which appears at the end of the 16th century, is

derived from the noun apposal (meaning

"opposition"), indicating "a

question for solution".

Others assume

that the noun is in fact derived from the verb,

which, in its earliest examples, means "to

put in embarrassing material circumstances, to

bewilder, to perplex". Some connection may

also be found with a much earlier adjective poselet,

meaning "confused, bewildered", which

ceased to be used by the end of the 14th century.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

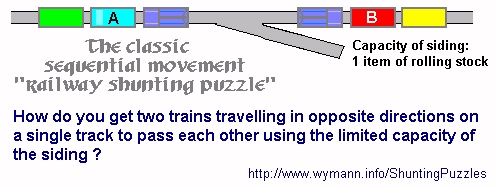

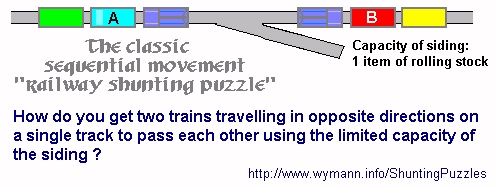

Sequential

movement puzzle + trains = "the shunting

puzzle"

|

|

| |

| Jerry Slocum & Jack

Botermans, who are the authors of a scientific study of

the history and principles of puzzle games (Puzzles Old

and New, University of Washington Press, 1992), provide

an in-depth look at sequential movement puzzles. Sequential movement puzzles are related

to the well-known solitaire or peg puzzles, as well as

the famous Rubick cube. The solution to this type of

puzzle requires a user to follow a series of sequential

movements within a set of strict rules in order to arrive

at a predetermined result. Many puzzles of this type

first appeared during the 18th and 19th century in

Europe, often devised by mathematicians because they

involve certain principles of topology, number theory,

and combinatorics. However, as most of these puzzles are

intended to be fun, they can actually be solved with a

very basic mathematical knowledge - very often, logic and

trial-and-error are quite sufficient.

One very famous such

"mathematical puzzle" is in fact called the railway

shunting puzzle.

|

| |

| There are a number of variations,

but basically the problem which needs to be

solved is that there are two trains facing each

other on a single line with just one short siding

(which won't hold one of the two equally long

trains completely) available. In order to enable

the two trains to pass each other and continue

their journey, a string of sequential movements

using the siding is required. It's quite a

brain-teaser, which probably explains why railway

companies all over the world took the more costly

but easier way out and built passing sidings... |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

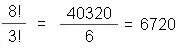

| A question which is

often asked once the concept behind a shunting

puzzle layout has been explained is as to the

degree of complexity or, in other words: just how

many possible configurations are there? The

mathematical approach to finding out how many

permutations a specific shunting puzzle allows

for is fairly easy. If "n" is the total

number of cars on the shunting puzzle layout, and

"k" is the amount of cars which are

selected from this, then the formula to be used

is

meaning that n

factorial is divided through the factorial

of n minus k (the “factorial” of

three, for example, is 1 x 2 x 3 = 6, and written

as "3!"). Applied to the original

Inglenook formula (where 5 cars are selected

froma total of 8), the calculation is as follows:

That

is to say: the 8 cars can be arranged in 40,320

different ways on the Inglenook layout, and the

number of possible trains with five cars which

can be made up from these is 6,720 (note that

this calculation only takes into account the

rolling stock present on the layout and

disregards the distribution of the three

"empty slots" in the sidings, as these

are not part of the object of the puzzle itself

and only serve as manoeuvering space; if you were

to factor them in then the number of combinations

rises significantly).

In

other words: if you were to systematically work

your way through these combinations, solving four

shunting tasks in one hour, and doing that for

three hours every evening, you would be at it for

560 operating sessions totalling 28 hours.

The true beauty of a

shunting puzzle is the simplicity within the

complexity: both Inglenook Sidings and

the Timesaver have simple rules, are

easy to understand, straightforward to build, and

great fun to operate and solve.

|

|

| |

| |

Further reading

|

| |

|

| |

| Simon Blackburn is Professor of

Pure Mathematics at the Department of Mathematics, Royal

Holloway University of London. This article looks at the

Inglenook Sidings from a mathematical perspective and

answers the question when you can be sure this can always

be done, while also addressing the problem of finding a

solution in a minimum number of moves. |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

Page

created: 23/SEP/2002

Last revised: 27/JUNE/2023

|