|

| |

SMALL

LAYOUTS &

SHUNTING

LAYOUTS

THEIR

HISTORY, CONCEPTS & OPERATION

|

| |

| The

status and the perception of small layouts as well as of

dedicated shunting layouts has changed significantly

within the railway modelling community over the past few

decades. Once a modelling niche they have become a layout

type bordering on mainstream. Here's a brief overview of

how and why this happened, the advantages of small

layouts, and how they relate to shunting layouts. |

| |

| |

SMALL

LAYOUTS

How small is "small" ?

|

| |

| Describing

any object as small is, of course, not a very accurate

label as it requires a point of reference: small in

comparison or relation to what? In addition, we all know

that certain objects can change their dimensional

qualities. |

| |

Source: Model

Railroader

|

|

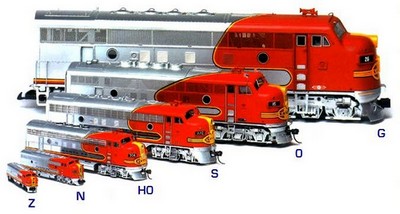

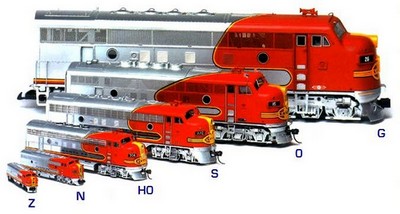

When

compared to its G scale counterpart, an HO scale

locomotive will appear to be quite small, but

that very same engine will appear big when we

view it alongside a Z scale model. The notion of size in model railways

changed as smaller scales were introduced over

time: HO (1:87) in the early 1920s, TT

(1:120/1:130) in 1945, N (1:148/1:160) in 1962,

and Z (1:220) in 1972.

A similar change - although only partly

linked to the introduction of smaller modelling

scales - has occured in the perception of just

how small a "small layout" can be for

it to be worthwhile to build and run trains on.

|

|

| |

| From a historical

point of view, the implicit message of the increasingly

popular (and therefore influential) model railways hobby

press was to "think big" and to be inspired by

modelling giants such as John Allen (whose Gorre &

Daphetid layout filled an entire basement from floor to

ceiling in his California home) or the Pendon Museum

layout (which fills the entire sprawling ground floor of

a building in Oxfordshire). In his 1978 Creative Model

Railroad Design, John Armstrong concluded that,

based on a Model Railroader survey, model

railroaders were indeed "denizens of the

basement" as that was precisely where 51% had their

layouts. 20% were located in a spare room, 7% in a

garage, 4% in the attic, and another 4% had a

purpose-built added room. In other words: at least 86% of

the participating modellers in the late 1970s indicated

having a spacious setting at their disposal - and thus

felt no constraint to not go for a "basement

empire".

|

| |

| This was

not, however, the case with British and European

modellers, who have seemingly always been plagued

more by a lack of space than their American

colleagues - and the more restricted options

available to them ultimately created the

archetypal British "branchline terminus to

fiddleyard" layout. In terms of track design, the

fiddle yard is a simple staging area

with a number of tracks which allows the

rearranging of trains off the layout proper. It's

true importance, however, lies in its conceptual

design:

"The basic

idea is simple. You just end the layout in a

few parallel sidings, and carry out any

necessary rearrangement by hand. These

sidings represent the rest of British

Railways." (Freezer, 1961)

The fiddle yard started to appear in the late

1930's when British modellers wanted to operate

small layouts in a realistic manner; in the

1950's, Cyril J. Freezer would regularly feature

fiddle yard to terminus type layouts as editor of

Railway Modeller and as such had an enormous

influence in spreading the concept and making it

popular - adding his own design,

"Minories", to the classic track plans

of that layout type.

|

|

|

|

| |

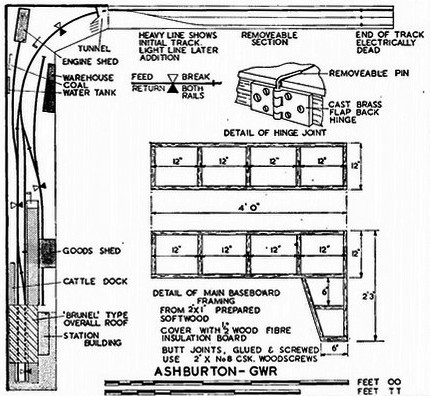

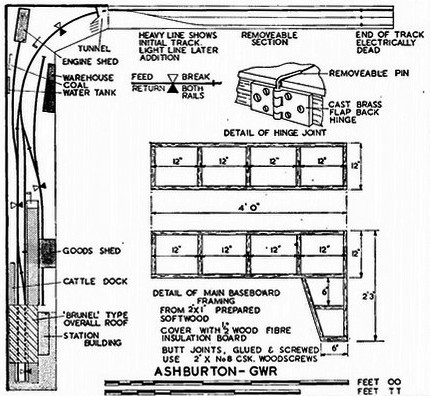

The example shown here is from the August 1961 issue,

in which Freezer pointed to another feature often

associated with terminus to fiddleyard layouts: the L

shape.

"The principle of the

L is to occupy two walls of a room, one leg being a

small terminus, the other a set of fiddle sidings.

These are perhaps the greatest post-war development

in our hobby, since they have enabled the

space-starved enthusiast to own a prototype

layout." (Freezer, 1961)

It became nothing less than a

blueprint for legions of British layouts and is still

widely featured today simply because it is a proven

concept. Also used in European modelling, though often

for the purpose of switching trains "behind the

scenes" on a continuous run layout, it is known to

German modellers as Schattenbahnhof, literally

meaning "a shadow station", i.e. not intended

to be visible to any onlookers.

Freezer was a good friend of Linn

H. Westcott, whose track plan designs were as influential

in the US as Freezer's were in the UK. However, this

didn't stop the concept of what would be called a

"small" layout going off in completely separate

directions in the UK and the States. While UK modellers were busily building what

would come to be called "shelf layouts" with

fiddle yards, a small layout to their American cousins

was more like a solid plank measuring 4'x8' (120 x 240

cm).

|

| |

|

|

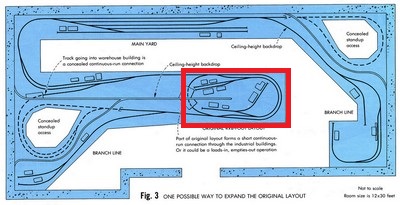

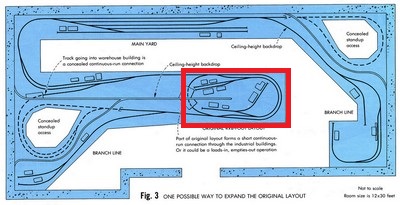

When Model Railroader

published a collection of track plans in 1981

from past issues of the 1960's and 1970's,

prolific track plan designer Ed Vondrak presented

"a small track plan designed for

growth": a solid 4'x8' (or preferably

even 5'x9') continuous run which could be

incorporated into a larger pike later on - and

the accompanying design once again pointed model

railroad planers to the basement or a spare room. One or two truly small

layouts are present in the publication, but they

were labelled "portable layouts". And

again, it ultimately all pointed to a much larger

setting.

|

|

| |

"Portable layouts

offer the chance to model railroad with a minimum

outlay of space, expense, and time. They allow us to

practice the fundamental concepts of layout design

which we will need to understand when the time comes

to build that larger, permanent layout."

(E.S. Seeley Jr., in Hayden 1981)

|

| |

| Driven by an entirely

different perspective and mindset, British

railway modellers continued to develop the

concept of the "terminus to fiddle

yard" further, effectively shrinking it from

running around two walls of a room to a short

linear layout - and the resulting "shelf

layout" formula gradually became an accepted

mainstream practice for those who wanted a layout

but lacked the space and/or the inclination to

build a fully blown mainline setup. The prototype

settings modelled continued to be mostly

backwater branchline terminus stations, but the

approaching line of track got shorter and

shorter. |

|

| |

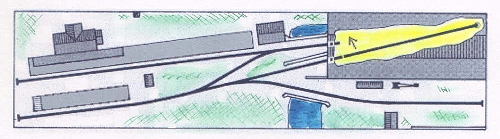

| A

very compact (4'-6" x 13" / 135 x 32,5

cm) example of this type of British shelf layout

is Dennis Beale's "Raikes Street" (an

article on this layout appeared in the January

1995 issue of Railway Modeller), which

differs from other shelf layout settings by

featuring a moveable piece of track concealed

within a factory building which drastically cuts

down on the speace needed for its runaround track

arrangement. |

|

|

|

| |

| In contrast to this, back in

December 1992, Model

Railroader featured a project layout built to the

"classic US" 4'x8' oval continuous-run formula

and labelled it as "a small layout anyone can

build". This is not to say that short

and narrow layouts were unheard of in US modelling - but

they were the exception to the rule and generally few and

far between. |

| |

| |

Small layouts: (almost)

mainstream modelling

|

| |

| But things were slowly changing -

the popularization of the internet since the

mid-1990s gave new railway modelling ideas a

massive boost as the world wide web profoundly

changed the way the hobby communicates and

conducts research. The popular hobby

magazines on both sides of the Atlantic were

still showcasing big and beautiful layouts, but

the railway modellers who first took to the

internet were less so inclined. Very often, the

layouts they were building, operating and

describing on the web were small shelf-layouts,

some of them even in "minimum space".

One important

such example which became a source of inspiration

for many was Scot Osterweil's NYC Highland Terminal

switching layout, which made its online debut in 1994

(Scot presented an update in Kalmbach's 2015 How to Build Small Model

Railroads).

But it was not all virtual

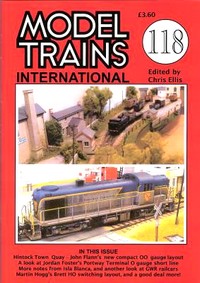

- in the UK, Chris Ellis, former editor of the Airfix

Magazine, produced and published Model

Trains International, highlighting a

modelling approach which was the pure anti-thesis

of the sprawling British "Railway of the

Month" and the US "Basement

Empire" and focused on shortlines pretty

much around the globe (MTI, which had a

small but loyal readership, ran for a total of

118 issues before being cancelled in 2015 as

Ellis retired).

Gradually, the concept of building and

running a small layout in its own right and not

as a stepping stone or a stop gap on the way to

the XXL size "dream layout" had

progressed into UK (and, to a lesser extent,

European) mainstream modelling.

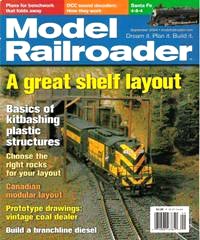

It also

started to appear more and more in North American

modelling, as the cover of the September 2004

issue of Model Railroader shows.

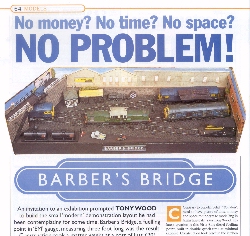

Even smaller layouts

started to appear in the UK, which were just one

little step up from a static diorama - such as

Tony Wood's Barber's Bridge (which was

featured in the January 2000 issue of Rail Express

Magazine).

An absolute minimum-space layout, the scenic section of this diesel

fuelling point measures only 22" x 8"

(55 x 20 cm), with an additional 14" (35 cm)

of hidden track allowing for movement of the

locos onto the three short sidings. The layout

was built within a few weeks and at a cost of

just £20 at the time.

|

|

|

|

| |

Over the years, various concepts evolved

around what came to be called "minimum space

layouts" in British modelling terminology.

Most of these center on how to run trains on a

small layout in order to sustain interest in it,

but some have taken up the question of how small

a layout can get and still be workable, leading

to a whole range of "micro layouts"

which really are as small as you can probably

get.

This modelling concept

found its master in the late Carl Arendt, whose

excellent website on micro layouts is still being run and

updated to this day: the micro and the

minimal space layouts really form a special

category of small layouts (which often also allow

the use of larger modelling scales in spite of

the small overall layout footprint, such as e.g. Jim Read's O Gauge 7mm

micro layouts).

Carl Arendt's

early internet presence (he launched his website

in 2001) along with his books no doubt helped to

make the concept more popular with North American

modellers.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Just to which extent the

popularity of small layouts has grown in the US can be

seen from the fact that Model Railroader issued

a special edition on how to build and run small layouts

in January 2015. |

| |

|

|

The

layouts portrayed include a wide variety of

structural concepts (including a modular

approach) but they also illustrate that the

understanding of what can rightfully be called small

is still open to interpretation as room sized

pikes find their place as well (where possibly

the characterization narrow would be

more appropriate as they tend to run along the

walls of a room). Also included is a portrayal of

John Allen, who way back in the 1950s already

felt that modellers should

"start

small and build well. Plan your small

railroad for operation rather than as a race

track, and build it with care. You will be

amazed at how much fun a small pike can

be."

How

much the "small layout" has shrunk over

time can be glanced from the fact that his

original Gorre & Daphetid RR - to which Allen

was refering in the quote above - had a footprint

of 3'-7" x 6'-8".

Newer layouts depicted

in How to Build Small Model Railroads,

however, show a clear tendency of leaning more

and more to the (smaller) British / European

shelf layout concept.

A follow-up publication

in 2018 titled Build a Small Railroad

offered a similar collection of smaller and

not-so-small layout concepts.

|

|

| |

| |

Small layouts:

real world inspiration

|

|

| |

| Small layouts may be the

modeller's solution to fitting a layout into a restricted

amount of space, but cramped locations served by trains

are an aspect of the real world. |

| |

| Some of the

plentiful examples to be found in urban and

suburban areas, where man-made obstacles such as

buildings and streets provide quite the challenge

of how to fit in tracks and trains, still survive

today. But the resulting complications (often

involving numerous shunting moves and awkward

loco movements) are the reason why many such

locations are no longer rail-served today. But back in July 1974,

passenger trains were still running through the

cramped streets of Weymouth on their way to and

from British Railways Southern Region's harbour

terminal, connecting with ferry services. Things

were so cramped that, for safety reasons, trains

had to be "walked" by railway staff -

who were also in charge of clearing the route of

people and badly parked cars. On occasions trains

were even escorted by British Transport Police.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Originally built in 1865 (most

certainly in less constricted quarters), regular boat

train services ended in 1987. Special train running

continued until May 1999, and after two decades of

mothballing the line was dismantled in 2021. |

| |

|

|

But cramped

locations were just as

plentiful in more bucolic rural locations. And

whilst these too have often lost their rail

services for the same reasons as their urban

counterparts, trains were still running to

Ventnor, the terminus station of British

Railways' Isle of Wight line from Ryde, back in

February 1966. In order to reach the station

trains had to run through a long tunnel and, when

emerging from the steep cliff of St Boniface

Down, immediately faced a three-way-point. This

had been installed to do away with the need to

use a turntable for runround moves of locomotives

- although these still had to enter the tunnel

during any such manoeuvres.

It is a scene that many

modellers would almost instantly discard as being

"unrealistic", and yet Ventnor (closed

in April 1966) was by no means a singular case.

|

|

| |

| Obviously, small layouts don't need to be based on

locations such as Ventnor, but it serves to provide

interesting cues for layout planning on how real-world

surveyors and rail companies dealt with the problem of

restricted space. |

| |

| |

Operation - the

key to sustaining interest in a small layout

|

|

| |

| On any layout - big

or small - you can either be running trains or operating

trains. "Running trains"

obviously is a broad concept. All it really indicates is

that model trains must be moving some way or another. At

one end of the spectrum, they might just be orbiting on

an oval of track at top speed, and the train might

consist of an American diesel locomotive, a couple of

Australian passenger coaches, one Swiss restaurant car

(complete with pantograph for overhead electrification),

and last but not least a British guard's van. However, in

railway modelling lingo "running trains"

usually indicates something at the other end of the

concept, namely aiming at creating a coherent picture of

both the trains and the environment they run through.

This would mean that American locomotives of a certain

period pull American rolling stock of (more or less) the

same period while running through an American landscape

of (more or less) the period in question. The amount of

compromise allowed may vary, but in general "running

trains" means that a layout will reflect some amount

of coherence and accuracy.

|

| |

| "Operating

trains" goes one step further, although it

doesn't necessarily imply a higher degree of

prototypical accuracy in terms of rolling stock

and all that goes with it. The word

"operating" is used, above all, to

indicate that models are run to reflect - but not

necessarily faithfully replicate - one very

important and central aspect of any real railway

: there's a purpose to it.

On the real railways, trains hardly ever

move "just like that". Maybe it's to

earn revenue by transporting passengers - such as

the British Rail Southern Region Electric

Multiple Unit (EMU) calling at Clapham Junction

in 1971 - or maybe it's to maintain the

infrastructure, which is the basis of being able

to run such revenue earning trains - such as the

two trains involved in extensive trackwork at

East Croydon in 1983.

These two scenes may be views from

specific areas and eras, but the same procedures

take place time and time again on rail networks

the world over.

"Operating" trains on a layout

is therefore an attempt to mimick this by

attributing a purpose to most or even all moves

taking place. Some of the concepts applied in

order to achieve this were formed in the context

of basement empires, others were developed

explicitly with small layouts in mind. Some

attempt to be as close to actual prototype

operation as possible, while others are loose

interpretations.

|

|

|

|

| |

| For

small layouts, the equation is a simple one: the lack of

space needs to be compensated by more interest generated

by the moves which take place on the layout. |

| |

Operational

concept: what a small layout is all about

|

|

| |

| Copying

the real rail transportation system's way of functioning

requires a concept. This doesn't mean that things have to

be complex or complicated - in fact, a simple concept

usually works best. A good basic way of starting is to

establish where the model railway system is located, the

era, and how it is connected to the rest of the world,

because these few points determine the traffic patterns

of a layout and thus provide

a reason for its existence - because on the real thing,

traffic pattern means customers and revenues, and without

those, railways will grind to a halt and disappear very

quickly. |

| |

|

|

There are a

number of operational concepts which can be

applied to a small layout. You

could have mainly passenger services, or

passenger services with an equal share of

freight, or freight only, or even a specialised

setting with specialised traffic, such as a

motive power depot or a civil engineer's yard.

One possible example to illustrate this point

comes from the preserved Kent & East Sussex Railway, where an English Electric Class

08 0-6-0 diesel shunter is ready in April 2001 to

shunt stock at the railway's main station site at

Tenterden.

|

|

| |

| All of

these options are feasible, but in practice layouts which have a strong

emphasis on what can be seen as "localized

operation" (i.e. so-called "shunting" or

"switching" layouts) feature a predominance of

freight operations or are even freight-only. |

| |

| This kind of operational concept

is usually the best choice if the layout

needs to be small - simply because it

provides a "realistic feel" and

even prototypical operation within

baseboard measurements which are open to

(almost) everybody. The reasons for this are quite

simple: shunters are usually relatively

short engines, and freight stock is

usually a lot shorter than passenger

coaches.

The example

shown here is a Class 08 diesel

locomotive trundling through the English

countryside with a trip working,

consisting of a short rake of assorted

waggons.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Both Tenterden and the tracks in

a cutting, spanned by a bridge, convey the constrained

space often replicated by modellers, i.e. "cramped

quarters" with a lot of track in a small space. Certain

rail served industries however tend to have large

footprints and a sprawling concourse in which shunting

takes place - such as Conrad Yelvington Distributer's

aggregate terminal in Wildwood Florida, where the local

Alco S2m presents an image of a "switcher in a

landscape" in May 2014.

|

| |

|

| |

| |

SHUNTING LAYOUTS

|

| |

| Every

country has its own approach and philosophy regarding

railway modelling, which often reflects the basic

characteristics of its own prototype railway system. |

| |

|

|

It

is therefore hardly surprising that mainstream US

railroad modelling focuses primarily on freight,

and switching layouts have been a popular facet

of North American prototype modelling for a long

time and feature frequently in magazines - such

as the Boston Union Freight Railroad, taking

center stage on the cover of the September 2000

issue of Model Railroader. Contrary to this, a

British outline model railway layout completely

devoid of any form of facilities catering for

passengers has for the longest time been unusual

to say the least. Nonetheless, the earliest

published example of a freight-only concept for a

layout seemingly comes from the UK: In the June

1926 issue of Model Railway News, A.R.

Walkley, a member of the Wimbledon Model Railway

Club (the second oldest in Britain), published an

article on his "Railway in a suitcase",

which was pioneering in terms of being H0 scale

two-rail.

The layout

also featured a system of automatic coupling

(really an essential feature for a shunting

layout) which later on was marketed by Tri-ang,

became known as the "tension lock

coupler" and is still used as standard

coupler on many UK ready to run models today (thanks

to Morgan Lee, longtime librarian of Wimbledon

MRC, for much of this information).

|

|

| |

| In

terms of British railway modelling history, Wakeley's

layout can be regarded as the ancestor of all UK shunting

layouts, as it concentrated entirely on freight . |

| |

| On a historical note, Walkley -

together with two fellow modellers from the then

newly-formed Wimbledon MRC (A. Stewart-Reidpath

and Michael Longridge) - began experimenting with

models roughly half the size of the established 0

gauge sometime in 1923. In the end, the three

modellers found 3.5mm scale to be the ideal

modelling ratio - and H0 scale was born. |

|

|

|

| |

| Another

typical example of the "1' x 4' shunting

layout" type is Dave Howell's "63rd Street

Yard" - an urban yard

with a couple of freight facilities and a low-relief

backscene for added atmosphere. |

| |

Trackplan

(c) Dave Howell, used with kind permission

|

|

An American

layout as the name implies, switching moves are

taken care of by a GE 44 tonner and an S2, with

40' boxcars the staple freight stock. The 3-way

point is both a space saver and an added bonus in

creating the feel of a small and tight but

sprawling urban yard. However, shunting layouts need not

necessarily be small - they can be enormous too,

if for example they incorporate large

classificiation yards.

|

|

| |

| The CSX yard in Wildwood,

Florida, would not be described as overly big by

prototype standards, yet it has a spacious and sweeping

layout and overall atmosphere which would be impossible

to model in a small space without losing much (if not

all) of its characteristics. |

| |

|

| |

| But

even when you go for a small, shelf-type shunting layout,

it's not necessarily the lack of space which provides the

motivation for this. A number of people opt for this kind

of layout because it provides interesting operational

possibilities. |

| |

In his booklet 60 Plans for Small Locations

(first published in the late 1950s, revised in

1989), Cyril Freezer - aforementioned grand old man of

British railway modelling and layout design -

touches on the shunting layout under the title of

"special purpose layouts" and points

out that:

"It is not obligatory to

incorporate passenger facilities into a

layout, and indeed there can be very real

benefits when a small layout is designed

around a specialised service."

However, only

3 or 4 of the 60 layout plans in the booklet

reflect this statement, and to this day, the vast

majority of British modellers seem to suffer from

horror vacui in the absence of passenger

facilities on a model railway layout. More

recently, however, the internet - having gone

from a niche interest in the mid-1990s to now

being the single most important source of

information and communication platform for all

hobbies -has helped change this heavily lopsided

approach to British railway modelling.

Searching in Google for "switching

layout" yields approximately 41,800 hits

(December 2021); the string "shunting

layout" is less frequent, but around 20,900

webpages will still keep you busy perusing their

content. Plus, layouts depicting shunting yards

or switching areas are popular topics in many

online discussion groups and fora.

Operational concepts for small

shunting layouts

As their name clearly implies, small shunting

layouts already have an operational concept and a

purpose to sustain interest in running locomotives and

stock on it: shunting - which is defined

by the Oxford English Dictionary as "pushing or pulling a train

or part of a train from the main line to a siding

or from one line of rails to another"

(its equivalent in North American railway

terminology according to the US Department of

Transportation being switching).

|

|

Class 08 diesel shunter on the British prototype

layout

Little Bazeley (above)

EMD SW1500 switcher on the US prototype layout

Pecan Street (below)

|

|

| |

| As

with any layout regardless of its size, a good basic way

to start building up a concept is to establish the

geographical setting and the era of the shunting layout

as well as how it is connected to the rest of the world.

These few points determine the

reason for its existence - in the form of its traffic

patterns, customers and revenues. |

| |

| On a small

shunting layout, there's usually only a handful

of customers receiving and generating freight. If you

take the following trackplan as an example,

things might look something like this.

|

|

|

|

| |

| The four

customers here are represented by the first four letters

of the alphabet, but you could just as easily use the

four suits of a deck of cards, so that A = Hearts, B =

Spades, C = Diamonds, D = Clubs. A deck of cards is

shuffled and a card drawn for each freight car on the

incoming track (e.g. the lower right hand track in the

diagram above). Thus the first car in that row of

incoming traffic may draw a card of spades and be

required to be moved to industry B (= spades), car #2

hearts (industry A = hearts), etc. |

| |

|

|

The problem with the traffic flow

generated by this system is that it doesn't take

into account the differences between customers A,

B, C and D, because rolling stock is moved to

locations regardless of its type and thus the

goods it may transport. However, if customer A is

a printer (who would above all want to receive

paper and ship printed products), he will quickly

turn his back on the railway if it keeps sending

tank cars and coal hoppers to his loading dock. |

|

| |

| A sound concept

therefore indicates the specific types of freight

received and shipped by each industry on the layout so

that only appropriate rolling stock may be delivered to

any given industry. In fact, even one single customer may

have different transportation requirements at different

locations. In this following example, still

based on the same trackplan, the entire layout serves

just one customer, a paper manufacturing plant.

|

| |

| Building "B"

is the loading dock for the finished product,

i.e. it ships paper. Building "D" along

with the adjacent tanks is the storage area for

both liquid and solid chemicals used, while

"C" is the unloading dock for collected

paper to be recycled and "A" the

unloading dock for cellulose. |

|

|

|

| |

| While this is

obviously a simplified layman's idea of how a paper

manufacturing plant might work, it provides the shunting

layout with a clear concept of what is and what may be

moved where and why. On the basis of this traffic flow

concept, a detailed list can now be drawn up, indicating

which type of rolling stock may be used where. For

example, tank cars will only be dropped off at

"D", whereas covered freight cars may go

anywhere (possibly arriving full, dropped of at

"C" first and then, once unloaded, moved to

"B" for loading). Special consignments

(delivery of heavy machinery or spares) may allow for

special freight stock. Here are five views taken in

April 2002 depicting the internal rail service at the

cardboard factory in Deisswil (Switzerland), illustrating

typical aspects of this type of traffic (since shut down

along with the factory).

|

| |

|

| |

| Motive power is

provided by a small company-owned shunter (which was

acquired new in this specific case, but which could well

be a second-hand shunter bought from a larger private or

state-owned rail company). The track is both covered (in

places where road traffic needs to have access) and

ballasted, with fencing present prominently - after all

this is private property. The factory buildings represent

a mix of older and more modern structures, and different

types of freight rolling stock to meet the requirements

of the rail customer - in this case tank cars (for liquid

chemicals), covered freight cars (for solid material

which needs some protection) and open freight cars,

covered with tarpaulins in some cases, for material which

will not suffer from exposure.

|

| |

| The

advantage of an operational concept governing traffic

flow is added realism and an extra challenge when

switching. The setback is just as evident: the example

above is definitely not suited for a layout which boasts

a collection of 20+ coal hoppers - unless the plant

actually runs on coal. |

| |

| |

Traffic

flow - what goes where and why

|

|

|

| |

| Once

an operational concept for a switching layout is drawn up

and established, the only thing needed to finally do some

interesting and challenging switching is to generate the

traffic flow. Over the years, a number of systems doing

precisely this (generally referred to as "car

forwarding systems") have originated with American

prototype modellers. Although rarely used for other

prototype modelling, all of these systems work equally

well for any kind of standard railway system. |

| |

| The specified

car switch list generates

instructions for freight cars on a layout, taking into

account their type and potential delivery locations. The

basic concept of most car card systems goes back to Doug

Smith's description in the December 1961 issue of Model

Railroader. The

most popular specified car switch list system is Don

McFall's Card and Waybill

system which works as follows:

|

| |

|

|

Step

1

The waybill is slipped into the transparent

pocket of the card, and the boxcar in question is

switched to the Consolidated Tooling Company for

unloadingStep

2

Reversing the waybill, the boxcar has now been

unloaded and loaded again; it is taken to its new

destination, the Atlantic Warehouses

Step 3

According to the directions on the waybill, it is

removed once the boxcar has reached its

destination, revealing that after unloading it is

to return empty to the Westside Yard

|

|

| |

| Obviously, these physical cards

can be - and to an increasing extent are - substituted by

virtual cards or screen output on a computer system or

handheld device which will also take care of the chance

car selection and load distribution. |

| |

| Whereas the card and

waybill system centers on identifying individual freight

stock and linking these with destination orders, the Scenario

List System

focusses on customers, i.e. locations and industries,

where freight may be picked up and/or delivered. |

| |

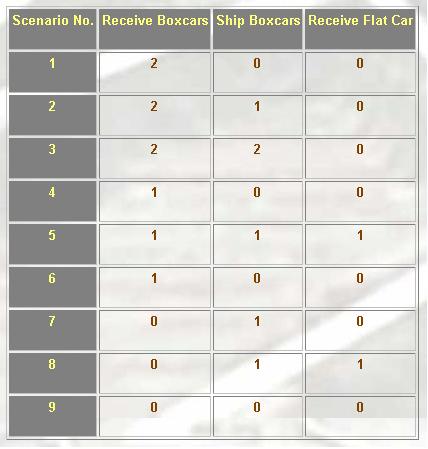

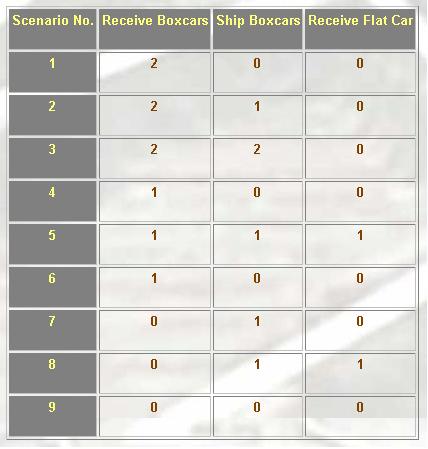

| Each

industry on a layout is analysed in terms of

possible scenarios. The Consolidated Tooling

Company, for example, is assumed to receive and

ship products mainly in boxcars, but occasionally

also to receive goods transported on a flat car.

The possible scenarios here are: Customer

receives 0-2 boxcars, ships 0-2 boxcars, receives

0-1 flat car. A selection is made from all

possible combinations in order to produce the

scenarios given as example here. For

every operating session, one of these scenarios

is selected for the "Consolidated Tooling

Co". In order to acknowledge that according

to the traffic flow concept worked out for this

customer some of these scenarios are supposed to

be more frequent than others, the scenario list

is broken down to scenario cards (one card giving

one scenario) in varying numbers. As a result,

scenarios 2 and 3 would appear on 5 scenario

cards each, whereas all scenarios involving the

delivery of a flat car would only have one.

Shuffling these cards, the chances of having a

flat car delivered would thus be smaller. Once

the "move" is made, the card goes to

the back of the deck of scenario cards, making

sure that flat cars won't appear too frequently

at the "Consolidated Tooling Co."

This

system works well for small layouts and is fairly

realistic in its approach: rail customers usually

don't care at all whether the boxcar used to ship

their goods is brown, green, yellow or pink as

long as they turn up on time and in sufficient

numbers.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Due to its

flexibility regarding choice of rolling stock to be used,

this system may not produce challenges in the sense of

asking you, by chance, to switch the most awkwardly

placed boxcar to the tightest spot on the layout - but

there's always the possibility of creating additional

rules if things seem to get too easy. |

| |

| |

Getting

real - car spots and the "modern

minimalist" approach

|

|

|

| |

| The majority of shunting and

switching layouts are rooted in what could loosely be

called the steam/diesel transition era - for two reasons.

First, as seen above, the concept began to be popularized

in the 1950s and 1960s, and secondly both motive power

and rolling stock from that era are considerably shorter

than their more modern counterparts (e.g. 40' boxcars

rather than 50' or even 60' boxcars) and therefore allow

for smaller layouts. |

| |

|

|

Combining this era (when even

less-than-carload traffic by rail was still

common) with the necessary compression of railway

modelling very often results in single-car

industries on shunting layouts. For modellers who

want to replicate current railway operations,

however, this conceptual formula simply doesn't

match up with the real world. For several years now a

number of modellers - who almost exclusively

model North American railroads - have come up

with ideas and answers on how to adapt the

shunting layout formula in order to make it both

workable and realistic for modelling the modern

railway scene.

Amongst these, Lance Mindheim is probably the

best known, as he combines stunning modelling

with a fully fledged concept of how to design,

build and operate a realistic (modern) switching

layout which he has highlighted in four books

published between 2009 and 2011 (How to

Design a Small Switching Layout, 8

Realistic Track Plans for Small Switching Layouts,

How to Build a Switching Layout, and How

to Operate a Modern Era Switching Layout).

His various Florida industrial park and spur

layouts have almost become a model railroading sub-genre,

inspiring many subsequent Sunshine State

switching layouts; Mindheim also runs a blog on

model railroad design in conjunction with his

commercial layout planning service.

|

|

| |

| Mindheim takes his cue from the

essence of what characterizes contemporary railroad

companies: their striving for efficiency in the face of

strong competition from road transport, which - if we

take the example of Norfolk Southern's Creed - translates

as "we will provide quality service, always

trying to reduce costs to offer competitive prices".

He then transposes this to modern railroad operations and

stipulates two main principles: |

| |

| 1 |

|

Keep the trackwork simple

A switch is a costly device: it requires handling

in the process of switching (costing the railroad

time while it's doing its job) and needs

maintenance (which actually costs the railroad

money). Therefore, contemporary track layouts

have done away with all unnecessary switches,

resulting in some cases in single track

industrial spurs of substantial length - which in

model form could mean a switching layout with

just one or two sidings.

A runaround track requires at least two switches,

and having the locomotive run around its train

consumes time and fuel, so the trackage in a

modern industrial park will most likely only have

switches pointing in one direction so that the

switcher can push and pull cars without the need

to run around its train. Therefore, you should

aim to not put a runaround where the prototype

doesn't need or have one. |

|

| |

| 2 |

|

Designate

multiple car spots for one switching

destination

The "one car customer" is, in

all but a few exceptions, a thing of the

past, and has been replaced either by

large rail customer complexes or by

switching destinations (such as a

warehouse) which in effect serve multiple

customers.

Therefore, you should have structures on

your layout with at least two designated

places where freight cars can be set out,

most probably serving more than one

customer. |

|

|

| |

| Putting these two principles to

work on a modern switching layout does take it very close

to being prototypically correct. The result from a

"traditional perspective", however, is a very

simple track layout which looks rather bare and most

probably also lacks one of the railroad modeller's

favourite devices, the runaround track, as well as other

"complications" such as switchback sidings

(which is why I refer to it as the "modern

minimalist" approach). |

| |

| However, unlike the traditional

steam/diesel transition era layout, the

operational "spice" on such a modern

switching layout is not generated by the

trackplan, but by the way the spurs and

industries situated along them are switched - by

using so-called car spots. As railroads

merged and lost their local foothold, names or

random numbers given to tracks serving customers

became incomprehensible to a centralized dispatch

structure.

Parallel to

the introduction of computer systems in the late

1960s, US railroads drew up industry schematic

maps for their road crews. They list industry

information such as where to spot loaded or empty

cars for unloading/loading for a specific

customer, the track capacities, and other

pertinent information, all in a consistent

format.

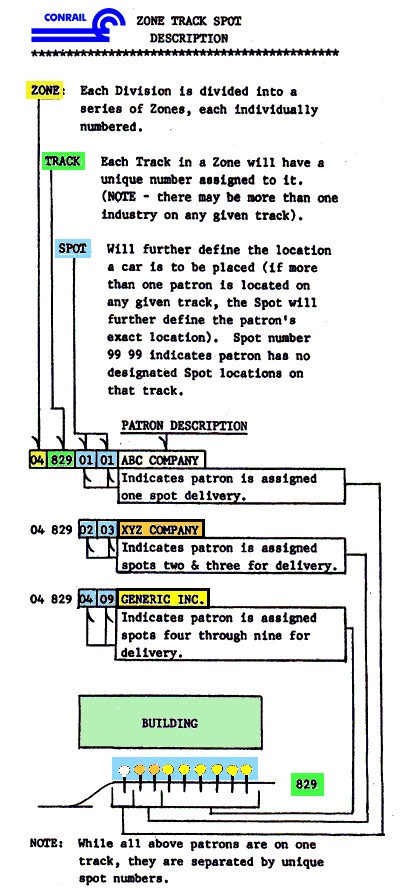

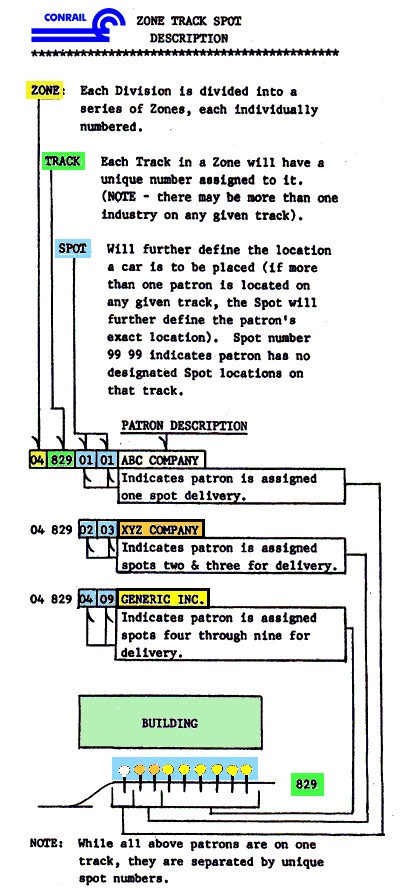

Different US railroads use(d)

differing terminology for this car spot

designation system; the acronym SPINS is an

abbreviation for Southern Pacific Industry

Numbering System - it originated on the SP

but was also used by e.g. BN. CLIC (Car

Location Identity Codes) was a Santa Fe term

for the same thing, as was ZTS (Zone, Track,

Spot) on Conrail.

The example

shown here comes from the 1987 Conrail ZTS for

its New England Division - and really explains it

all. If a freight car is to be set out at

04-829-07, then the ZTS map will tell any crew

that its destination is car spot 07 on track 829

in Zone 04, and that the customer in question is

the Generic Inc.

It is also easy to see how

requiring freight cars to be placed in specific

spots can add not only additional realism to a

modern era switching layout but also beef up the

challenge of operating it considerably. All of a

sudden, that single industrial spur doesn't seem

that bleak anymore.

The United Warehouse in Wichita

illustrates what this looks like in real life,

but even a drastically shortened building can

provide operating interest on a switching layout

using car spots if it either serves several

customers or a single customer requires specific

goods to be delivered to specific locations on

his spur.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Switching on a "minimalist

modern" layout will mostly consist of pushing and

pulling cars in and out of sidings until the required

order is arrived at - and as such is in fact very similar

to switching an Inglenook

Sidings puzzle. Just like the latter, cars could be

assigned spots by e.g. the random throw of a dice; in his

books, Lance Mindheim suggests setting up the switching

order yourself but making the most of the switcher's

moves by imitating certain prototype procedures and

remembering to take it slow as switching in 1:1 scale is

a time consuming job. |

| |

The conductor is

throwing a switch in Wildwood FL yard in May 2014 as CSX

"road slug" GP39-2 #2383 and GP40-2 #6983 are

busy pushing and pulling cars as described above -

although in this case they are not serving car spots but

rather "blocking" a consist, i.e. making up a

northbound train.

|

| |

| Again not necessarily small in

size, a modern era switching layout can offer a lot more

operating potential than its simple trackplan might

suggest if a car spotting system is used. Naturally, many

prototype locations still have more complex trackwork in

evidence today (a fact Mindheim and others are more than

willing to admit), but it is becoming the exception. And

ultimately the simple track layout has the same advantage

for the modeller that it has for the real railroad

company: fewer switches and less track means spending

less money on infrastructure and less time on

maintenance. |

| |

| Probably

the main attraction of a "modern

minimalist" switching layout is that it

allows the use of contemporary rolling stock with

single car payloads - which has become a rarity

in the age of the "block train"

(carrying a long string of freight cars loaded

with the same cargo, e.g. containers or coal) but

which used to be the railway's daily bread. Using

"car spotting" thus works just as well

for a 1950's or 1960's layout and is not

restricted to any geographical area at all. The new goods shed in Peterborough

embodied British Railway's perception of

modernised freight working by rail; goods vans

could be unloaded either into the goods shed

(where a conveyor belt helped in moving the goods

to their correct storage space) or outwards onto

road vehicules which distributed the goods

elsewhere.

|

|

A long row

of 12t goods vans standing at the newly

modernized Peterborough goods shed in 1960

|

|

| |

| It

was a 1960's version of a transload facility, which

certainly required the goods vans to be set out in the

correct order so that they ended up being

"spotted" where they were needed. |

| |

| |

From a

shunting layout to a shunting puzzle

|

|

|

| |

| All of the systems of

operating a shunting layout discussed above have one

purpose: to generate interest by means of a consistent

traffic flow. Although they may come up with some awkward

shunting moves, they are not designed to introduce such

complications deliberately. Most of the time, things will

flow easily. A shunting puzzle, however, is a

shunting layout which deliberately introduces

complications which need to be solved in order to get the

shunting done. Usually, these complications are generated

by a set of restrictions or rules. For example, sidings

can be short and thus require the operator to think ahead

of his moves unless he wants everything clogged up, or

rules may require a certain specific order into which

freight stock must be shunted.

The

example layout used above to illustrate a possible

operational concept based on a paper factory, by the way,

uses the "Timesaver"

trackplan - the classic US switching puzzle. The classic

British shunting puzzle, the "Inglenook Sidings", features a significantly less

complex trackwork, whilst a "tuning fork" switching puzzle reduces it all to

the max by only having one point and two sidings.

|

| |

More about Shunting

Puzzles

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY Freezer Cyril J.

(1961) "Another layout for the holidays", in Railway

Modeller (August 1961 issue)

Hayden Bob (ed.)

(1981) Track planning ideas from Model Railroader,

Kalmbach Publishing

|

| |

Text,

photos and illustrations not labelled otherwise are © Adrian Wymann

Page created: 26/JAN/2001

Last revised: 14/SEPT/2024

|

| |