|

There is nothing quite like popular culture to make you realise just how much the paradigms and tastes of any given period change as time passes. Comic books, of course, are no exception. But apart from illustrating how much the medium and its content have changed, looking back also provides substantial insight into how much the industry - and its market - have gone through a metamorphosis. |

WHAT A DIFFERENCE A DAY MAKES ... ... NOT TO MENTION 33 YEARS FAST FORWARD FROM FANTASTIC FOUR #186 TO FANTASTIC FOUR #580 |

| Standing in front of the almost endless shelves on the lower floor of Forbidden Planet's London megastore on Shaftesbury Avenue on a July day in 2010 and trying to take in all the various comic book titles lined up, all of a sudden the cover of the current issue of Fantastic Four caught my eye. "Hmm" I thought to myself as I was reaching out for a copy, "that cover somehow reminds me of FF #186". |

|

Now

contrary to what this might suggest, I will have to

confess that I am no particular fan of the comic book

title which started it all for Marvel in 1961 - a view no

doubt supported by the fact that my point of reference,

i.e. Fantastic Four #186 (cover date September

1977), was in fact the only issue of the original series

I owned up until that point in time - i.e. before I

bought Fantastic Four #580. Comparing the two comic books side by side provides quite a few points worth one or two minutes' thoughts, the first surely having to be that it is quite amazing to find a comic book title which had already clocked up 16 years and 186 issues in 1977 to still be around almost 33 years and 400 issues later. Now of course 2010 was the year Batman reached issue #700 in actual continuous numbering (which was not quite the case with Mighty Thor #600 in 2009), and both Marvel and DC turned out milestone issues by reverting back to the original issue counts (Captain America #600, Wonder Woman #600, Daredevil #500), whilst June 2011 saw Action Comics #900 and late December 2012 gave us Amazing Spider-Man #700. The accumulation of such impressive numbers seems to make people forget the fact that these issue counts contrast sharply with historical events which would have made such prospects seem very unlikely at the time (e.g. the 1978 "DC implosion" with the cancellation of 31 titles or the 1997 Marvel bankruptcy), and they also contrast sharply with a growing string of "mini series" (with a limited number of issues planned from the outset) and the many newly launched titles of the past few years which quickly fell by the wayside after a few issues only. No, make no mistake: it is indeed truly amazing to have Fantastic Four #580 and a comic book title which celebrated continuous publication for 50 years in 2011. |

| That said,

what's all this about the resemblance to the cover of Fantastic

Four #186? Admittedly, it may not be as striking as it appeared to me at first sight, but there are one or two points which match. The aspect which probably drew me in first was the similarity in which Alan Davis composed his cover for FF #580 with how George Perez and Joe Sinnott configured their artwork for the cover of FF #186: a circular arrangement of figures with a pronounced movement drawn to the center of the cover, as well as objects moving outwards from the focal point, i.e. the cover's center. |

From my limited knowledge it would seem to me that this is actually a very typical way of arranging FF covers, probably due to the team's somewhat default formation strategy of the Human Torch flying out to one side and "Stretcho", i.e. Mister Fantastic embracing opponents from the other side, with the Thing and the Invisible Girl often going into action in a full frontal move. Whatever, FF #580 struck a visual memory chord with me and FF #186. One aspect which is much more obvious, however, is the logo of the book which is absolutely the same, colours included. The famous tagline "The World's greatest Comic Magazine" is missing, replaced with a "Heroic Age" banner, and so are the four heads of the superhero family in circular vignettes, two on each side. However, had I picked up the previous issue, Fantastic Four #579, the familiar grouping of heads would have been there, just as it was in the Bronze Age of the 1970s.

|

| That is

quite striking, but it also says a lot about

"branding", although the logo on FF #186 is, of

course, not the original one, which featured the somewhat

curvy-curly but nonetheless familiar outline of the

comic's title. A more conventional comic book styling

using shaped block letters was introduced as of Fantastic

Four #119 in February 1972 before the font displayed

on both issues #186 and #580 was first seen on the cover

of Fantastic Four #160 (July 1975) up until

issue #217 - after which the title logo went back again

to its original curly letters in May 1980 and stayed with

the title even throughout some relaunches. Well, so much for similarities - let's now turn to the differences in those two covers. Apart from the fact that virtually all of Marvel's company cover regalia had vanished - reduced to a simple red box reading MARVEL.com and indicating nothing else other than the issue number - you will notice that Fantastic Four #186 carries a price indication in British pence whereas Fantastic Four #580 only has a US currency price, in spite of the fact that both issues were bought in the UK. The 12p price printing marks Fantastic Four #186 as a copy specifically printed in the US for export to the British market - also easily identified by the different wording in the band which ran across the top edge of the cover and which read "Marvel All-Colour Comics" (as opposed to "Marvel Comics Group" on US market copies) in order to set them apart from the black and white only reprints available through Marvel UK during the 1970s. |

Comparison of cover details from the Fantastic Four #186 US market printing (above) and its UK market counterpart (below) |

| Other than

those two points, these comic books were identical twins

of their US counterparts, produced during the same

printing runs but destined for bulk shipping to the UK,

which accounted for the fact that the pre-dating of the

US production run (where the actual publication date

would precede the cover date by three months) was

virtually lost in transit. Therefore, a US comic book

dated September 1977 would actually be on sale precisely

that month in the UK. Okay, so no UK currency price indication on the cover of Fantastic Four #580, and no sticker or anything on the back cover either. Matter of fact, I didn't know what those comic books I picked from the shelves in the Forbidden Planet Megastore - which were all marked with a cover price of $ 2.99 - would cost me before I was charged at the cash till and discovered that the price was actually £ 2.85 per comic. Apart from being a phenomenally steep rise in the price for a single issue - a point I'll came back to in a moment - this tells us more about the comic book market as a whole than meets the eye at first and even second sight. |

| Back

in 1977, I bought my copy of Fantastic Four #186

along with a number of other US Marvel comics at WH

Smith's High Street store in Sutton (Surrey), and "Smith's"

did indeed not only provide me with British comic

books throughout the 1970s but also offered me the much

appreciated opportunity to pick up copies of Marvel (and

DC) comics imported from the US. Today, WH Smith

(according to the company's website) "aims to be

Britain's most popular bookseller, stationer and

newsagent", and although that couldn't have

been any different in the 1970s, there are no more

individual US comic books to be found at a WS Smith store

even though they still stock the UK market reprints (plus

a fairly large selection of trade paperbacks). The answer to the question of why Fantastic Four #580 carries no UK currency price is the same as to the question why comic books have largely moved from newsagents and other outlets to specialist comic book shops: they have left the "general distribution market" for the "direct market". The emergence of the direct market in the US was a reaction to the fact that the business of producing comic books came under increasing pressure from the distribution and sales end of things. Low cover prices and therefore tiny profit margins made comics more of a nuisance than a moneymaker for resellers, and the number of outlets selling comics was falling fast during the early 1970s. By mid-1975 industry leader Marvel had lost $2 million, and the market for comic books shrunk to an all-time low in 1979 as Marvel's overall annual sales figures totalled approximately 5,8 million copies only (Daniels, 1991). This decline in sales and profits triggered various proposals for a radical reconceptualization of the market which finally led to the creation of the "Direct Market". |

|

| Generally

credited with having saved the comic book industry from

almost certain death (Groth, 2006), it streamlined the

distribution system and did away with the returns system

whereby newsagents could return any unsold copies and get

refunded; a business model which did nothing to encourage

actual sales and resulted in 65% of all copies

distributed by Marvel throughout the 1970s being returned

- and sometimes even reimbursed without any physical

proof (Groth, 2006). It is this switch to specialist shops which explains why WH Smith stopped carrying US comics for the UK market as of the early 1980s and resellers such as Forbidden Planet took over - incidentally, both companies started out in small premises in London (WH Smith in 1792, Forbidden Planet in 1978). And unlike the general newsagent, the specialist reseller can do without domestic currency price indications as regular customers will know the converted price anyway and others are free to ask. That then is the long answer to the short question why, unlike Fantastic Four #186, there is no UK £ price on Fantastic Four #580. And it also explains why you can no longer stop at a servicing area on the M4 motorway and be thrilled to find a copy of Chamber of Chills #25 and Crypt of Shadows #21 in the newspaper shop as I did as a kid in September 1977 - but I digress. Another difference worth noting is the aforementioned rise in the price for a single comic book issue. Given that 12p in 1977 had the purchasing power of roughly £1.00 in 2010 (according to measuringworth.com) and 30 cents (the US cover price for Fantastic Four #186) in 1977 equalled a purchasing power of $1.08 in 2010, comic books have become disproportionately expensive. However, there are several reasons for this, some of which hit you straight away when comparing issues #186 and #580 of Fantastic Four. |

|

Comparison between the low grade newsprint paper artwork and colour rendition in Fantastic Four #186 (above) and the high quality paper printing used for Fantastic Four #580 (below) |

First off, there's the quality of the paper and the move away from cheap newsprint grade paper to ISO 9706 certified permanent durable paper or high quality glossy paper which has been chemically de-pulped and coated with an alkaline buffer (Teygeler 2004). Newsprint paper was popular due to its low cost and high absorbency (which was well suited to high-speed presses), but due to high levels of lignin it discoloured and oxidised rapidly while setting free acids which degraded the paper material even further. The widespread use of higher grade paper by comic book publishers since the mid-1990s has greatly improved the artwork and colour rendition. Whilst the printing on Fantastic Four #186 is already an improvement over comic books from the 1960s, there is still a fair amount of blurred inking rendition and colour bleeding. As the paper used on Silver and Bronze Age comics never really was white even to begin with, the omnipresent yellowish hue (which increases over time due to the ageing process) always affects the colouring tones. The new paper quality and enhanced printing techniques have set comic books on a par with glossy magazines in terms of appearance quality levels. Comic books in the 1970s had "cheap" written virtually all over them, especially for those individuals who did not speak too highly of the medium to start with. Today, one of the initial arguments against comic books which was used in the 1930s and 1940s - namely comics beeing a "strain to the eyes of the young readers" - can no longer be voiced even by the most fervent anti-comics crusader. And as an added bonus, the artwork of pencillers, inkers and colourists is brought to the readers in a form of printing which actually does the efforts of these creative teams justice and provides a faithful rendition. In essence, comic books have thus moved up the ladder of items in print - they have left newspapers behind and joined the glossy magazines. The reason why prices for comics have gone up so much is therefore not only a reflection of actual increases in the production process through the use of higher quality materials and techniques, but also reflects the higher overall quality projection. The increased price per copy, however, also goes hand in hand with fundamental changes of what a reader can expect to find between the covers of a comic book in terms of content type and ratio. Both Fantastic Four #186 and #580 offer the buyer a total of 32 pages. However, only slightly more than half of these pages (17) carry actual story content in the case of FF #186, whereas this number has gone up to 23 in the case of FF #580, which equals a plus of 35% in comparison to FF #186. |

Obviously, this does not account for the far more than 150% increase on cover prices of comics on its own, but there's another aspect to be taken into account: given the unchanged total number of pages, the increase of actual story content can only be accomplished by reducing other content type. In the case of comic books, this simply means: less advertising - as a comparison of the content type page count of Fantastic Four #186 and #580 clearly illustrates. |

|

| In short:

the number of pages generating expenditure for the

publisher has gone up, those generating income has gone

down. Whether or not the actual price increase from 1977

to 2010 is justified or not, well, we can all have our

personal thoughts and opinions on that. I myself would at

least point out the fact that today - quite unlike the

1970s - virtually every single issue comic book is sold a

second time in the form of trade paperbacks; in fact many

comics these days give the impression of having actually

been written for the TPB format (witness the six issue

story arc which just so happens to nicely fit a TPB

volume) to the extent where the money made with monthly

issues seems to be neither the primary source nor target

of revenue. But I digress, once again. It is interesting to see that along with the reduction of its presence in comic books, the advertising content itself has also changed completely. Again, comparing FF #186 with issue #580 reveals to just what extent this transformation has taken place. In a Marvel comic book of the 1970s, two pages of story content were most often followed by two pages of advertising, and this structuring eventually created the famous line "continued after next page" at the bottom of a right hand page of story content. |

| True period pieces of advertsing and publication history of the 1970s, these pages no doubt were a real killer in terms of maintenance and accounting. In contrast, today's advertising in comic books is mostly full page, reducing administration and maximizing impact, as illustrated by the page on the right taken from Fantastic Four #580. |

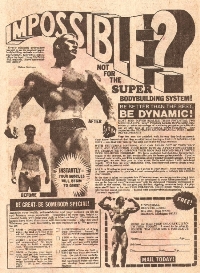

In actual truth, the "flea market" pages usually made up only one third of the total of advertisements in a 1970s Marvel comic book, and full page ads were not totally uncommon, as the example here - again taken from FF #186 and again an ad to reappear time and time again throughout the mid-1970s - shows. Some of these pages were only printed in black & white, further cutting down on costs. It is also quite noticeable that the actual content of ad pages has changed along with the format. The sometimes distinctly exotic products from the 1970s (such as bodybuilding equipment linked with the question "impossible?" and the immediate answer "not for the super bodybuilding system - be dynamic!") as well as food products (mostly snacks, of which the Hostess cup cakes are possibly the best known as they featured a variety of Marvel superheroes in a short story on one full page which had them praise the product at the end) have all but vanished from the pages of comic books and been replaced mostly by ads for electronic gaming software. |

|

| This is not

forgetting the fact that ads for cars also feature in

some titles, which clearly illustrates the increasing age

range of the readership. Another point of interest are pages featuring editorial content. This is the only content segment where there is no change in terms of page count between Fantastic Four #186 and #580, but the differences between 1977 and 2010 are nonetheless pronounced. First off, there is the traditional letters page. I label this type of editorial content "traditional" because these pages have been a regular feature of titles from all major comic book publishers throughout the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s. This changed when the growing popularity and presence of the internet saw the creation of various fora where comic book readers posted and exchanged opinions, and publishers closed down their letters pages. Contributions had gone down to a trickle, but when DC announced the end of this institution in their publications as of late 2002, the Washington Post even ran a front page article.

|

| Well, the Marvel mystique may still be around generally speaking, but the editorial pages hand out little to nothing of it these days (nowadays just as back in 2010) for the simple raeson that they are rarely seen. Fantastic Four #580 is actually an exception, but even though it does feature an editorial page which gives readers a peek behind the scenes, the style has changed completely. The slightly overdrive tone of the bullpen bulletin pages of the 1970s has been replaced by a distinctly matter of fact and toned down style of writing and presentation. This was all the more surprising as DC at the time published a regular last page editorial feature entitled "DC Nation" which was often fairly reminiscent of the old and slightly zany Marvel bulletin style. With the "New 52", that has pretty much disappeared again. |

Whereas the reader of FF #580 just gets to know about the Women of Marvel Celebration in general and Kathryn Immonen in specific, the editorial page from Fantastic Four #186 provided a whole treasure trove of reading material. First out of the starting blocks was, of course, Stan "the Man" himself who first off tried (no doubt successfully) to impress the readership by thanking the welcoming committee of the University of Alabama in conjunction with a lecture he was asked to give there. Secondly, he announced the return of comic books legend Carmine Infantino to the ranks of Marvel (with probably only few readers at the time knowing that, according to Ro (2004), Stan Lee had tried to lure him away from DC ever since around 1967) and that he would go to work for the first issue of a new ongoing title, namely Spider-Woman #1. And thirdly came the announcement of the syndication of Howard the Duck in newspaper strip form, all garnished with Lee's rhetorical question "Who says this isn't the Marvel Age of Magnificent Munificence?" and parting request that "if you can spare a minute or two, take a turtle to tea!". Well, Excelsior indeed, and the only question raised by that installment of Stan's Soapbox was, of course, just how many readers were fully aware that the not too commonly used noun munificience describes magnanimous generosity? Ah, but doesn't it just befit a lecturer at universities so well? Following up on this mix of infotainment, two thirds of the page actually still remained to be read, and spread out over this space were all kinds of announcements and bits of information, such as: the launch of various one-shot movie tie-in adaptations; Jack Kirby developing a new title (with more news next month); a parade of summer annuals; a new Conan Treasury Edition; and finally the first issue of a new title, namely Human Fly. Heck, it almost took you as long to read the Bullpen Bulletin as it did to read the actual comic book... It was obvious even to the thirteen year old that I was when I read Fantastic Four #186: this page was much much more than "editorial" - this was in many ways the essence of what Marvel comics were: content, yes of course, but infused with well balanced doses of zany humour, larger than life assessments of maybe not really that important happenings, and a tongue-in-cheek club atmosphere. Even if I didn't care at all about a Jaws comic book adaptation or had no idea at the time (shame on me) who Carmine Infantino was, I had fun reading about them. In that respect, the comparison between FF #186 and #580 possibly results in the sharpest contrast when looking at editorial input. In 2010, it virtually all and everything happens on the interweb site, with the exception of full-page in-house ads for specific titles for which, however, you are left to make up your own Bullpen Bulletin text. |

Finally, of course, all of this leads to the question: what will Fantastic Four look like in another 30+ years? That would be getting close to issue #1000, so just make sure you put down a note for that one. And don't forget: "If you can spare a minute or two, take a turtle to tea!". 'nuff said. PS. If by any chance you're wondering why this comparison of two issues of Fantastic Four doesn't deal with content at all - possibly delving into the different styles of storytelling and artwork prevalent in 1977 and 2010 - well, that's because that kind of comparison would be an entirely different story all together. |

| Suffice to say that if you want a synopsis of FF #186 you can find it here, as well as the wrap up for FF #580 which is available here. Maybe you will notice that the synopsis for the 1977 story is a lengthy one whereas the one for the 2010 issue is very short to say the least... but as I was saying: that's an entirely different story... hey, over there - isn't that a turtle ?! |

BIBLIOGRAPHY DANIELS Les (1991) Marvel: Five Fabulous Decades of the World's Greatest Comics, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. GROTH Gary (ed.,) (2006) The Comics Journal #277 (July 2006), Fantagraphics N.N. (2003) Stan Lee Interview, contained as extra feature on the double disk DVD release of the movie Daredevil (personal transcript) RO Ronin (2004) Tales to Astonish: Jack Kirby, Stan Lee and the American Comic Book Revolution, Bloomsbury STUEVER Hank (2002) "Comic books end printed mail columns as fans turn to web", in The Washington Post, Tuesday, December 10, 2002 TEYGELER R. (2004). "Preserving paper: Recent advances", in J. Feather (Ed) Managing preservation for libraries and archives: Current practice and future development, Ashgate Publishing |

first uploaded to the web 31 August

2010 The illustrations presented here

are copyright material

(c) MMII - MMXV |