There is nothing quite like

popular culture to make you realise just how much the

paradigms and tastes of any given period change as time

flies by. Comic books, of course, are no exception.

But apart from illustrating how much the medium and its

content have changed, looking back over the years, above

all, also provides substantial insight into how much the

industry and its market have changed.

|

| |

|

| |

| Welcome

back to a little bit of digging and excavating amidst the

artefacts of the world of comic books. This time around

we turn to Gotham City in what might seem like a time

paradox as we take a closer look at Batman #1

from 2011 and Batman #315 from 1979. The simple

explanation for this peculiar number count of Batman lies

with DC's (re)launch of their "New 52" in

September 2011 and the subsequent re-numbering of all of

the monthly comic book titles.

In-house

ad for DC's "New 52" relaunch

|

| |

| Hence the

premier issue of Batman, which strictly speaking

is thus #1 of volume 2, and which provided readers under

the age of around 80 (i.e. all those who weren't around

in 1940 to pick up the first Batman #1) with an

opportunity to buy and read a first issue of Batman

- the first renumbering DC afforded the title after a run

which had lasted 715 issues. |

| |

DC Website announcement for Batman

#1

|

|

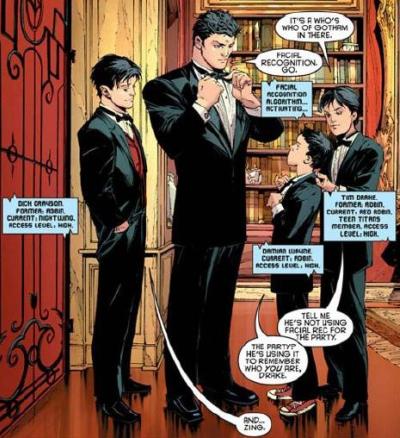

Apart from that - and in

spite of some high-profile hype from DC - changes

to the form and content of the immediately

preceding last issues of volume 1 were few and

far between (e.g. no origin story whatsoever),

other than the fact that Bruce Wayne was back as

Batman after a Grant Morrison odyssey (i.e.

"story arc") featuring Dick Grayson as ersatz

Batman whilst Bruce Wayne was somehow "cast

back in time" by Darkseid. Whatever -

readers trying to spot any differences would thus

be required to look further back in (real) time -

for example by taking a look at Batman

#315, the cover date of which (September 1979)

separated it exactly 33 years from Batman

#1 which was launched on 21 September 2011

(featuring the usual gap with regards to the

cover date, which in this case was for November

2011).

|

|

| |

| Naturally,

this discrepancy between the actual date of publication

and the date given on the cover (which in modern comic

book times is around 2 months) also held true for Batman

#315. However, for those comic books from DC and Marvel

which were sold in the United Kingdom during the 1970s,

that difference (which generally speaking used to be 3

months during that decade) virtually collapsed due to

shipping times. |

| |

| Seeking out the US comic

books imported for the British market at WH Smith

in Sutton in late

September 1979, I found that the overall

selection of titles from Marvel had shrunk

considerably in comparison to only two years

earlier. At the same time, however, I also

spotted a few DC titles imported for UK retail

for the first time at Smith's. The selection was

small and seemed somewhat odd, but I was more

than happy to come away with Batman #315

(cover date September 1979) alongside Unknown

Soldier #232 (October 1979) and House of

Mystery #272 (September 1979). Unlike

Marvel, which had been shipping its comics to the

UK with specially printed covers almost

continuously since the early 1960s, DC had not

taken up this dedicated distribution channel

prior to the early 1970s as US print run copies

simply received a UK currency price stamp on their

cover.

|

|

WH Smith, Sutton High Street

(September 2007)

|

|

| |

| The first

known examples of printed UK prices on the covers of DC

titles seem to come from 1971, but in any case supplies

were intermittent and unreliable throughout the decade.

In early 1979, however, DC seems to have made a conscious

effort for a while to supply the British market with

dedicated cover printings - although

"dedicated" might be too big a word. |

| |

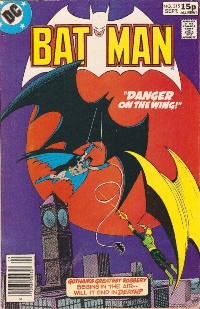

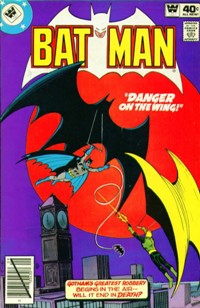

Batman #315

(September 1979)

UK 15p price variant

|

|

Unlike UK covers from Marvel

(where the masthead band MARVEL

COMICS GROUP was changed to MARVEL

ALL-COLOUR COMICS), UK covers

for DC titles only differed with regard to the

price. As a result, the difference in appearance

between the copy of Batman #315 I picked

up at WH Smith's and its US counterpart was

minimal and limited to the price indication.

UK cover price indication

15p and

US cover price indication 40c

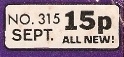

The difference between US and

UK priced DC covers was thus also markedly

smaller than between the regular issue and the

"Whitman variant" of Batman

#315, which features the prominent upper left

corner logo design used by Gold Key (Western

Publishing) for their newsstand distribution.

|

|

Batman #315

(September 1979)

US market 40c cover

|

|

| |

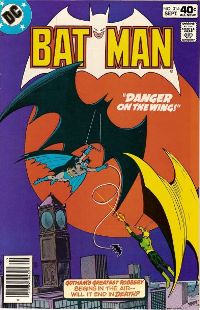

Batman #1

(November 2011)

US $2.99 price only

|

|

Batman #1,

in contrast, only carries a US market

price (which had risen from 40c to $ 2.99

in 32 years). Perhaps most strikingly,

the bat silhouette (which goes back

virtually to the first Batman #1

from 1940) underlying the branding BATMAN

remains virtually unchanged - a clear

indication of the iconicity of the

character. Turning back to 1979,

the facts of comic book distribution were

such that there was no guarantee for

consecutive issues of a given title to

actually show up and be on sale where you

had bought your previous copy.

The ensuing gaps in

continuity were, however, softened to

quite some extent by the fact that this

was the Bronze Age, and you thus stood a

fair chance of not missing anything in

the way of storyline because these were

still very much running on the "one

and done" formula, i.e. where a

story would begin and end in the same

comic book.

|

|

Batman

#315

(September 1979) Whitman variant

|

|

|

| |

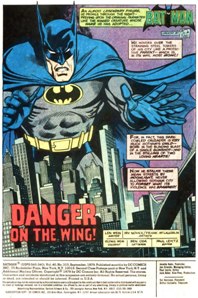

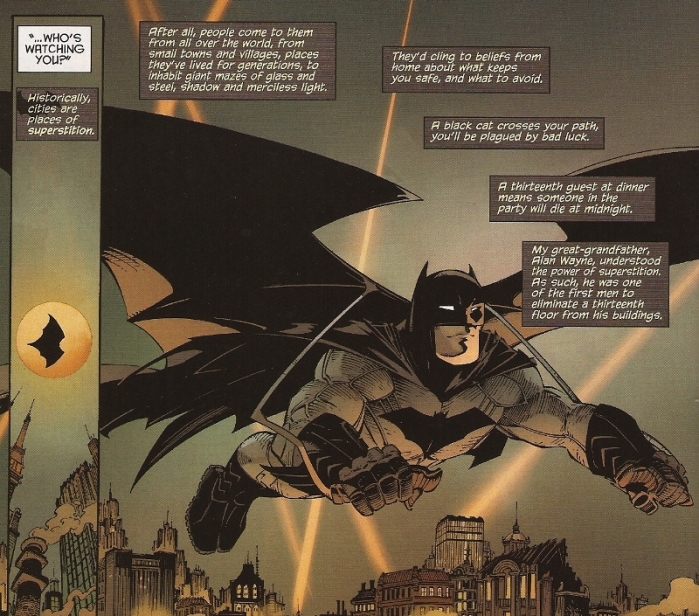

| This is

also the case for Batman #315 - "Danger on

the Wing" was written by Len Wein, pencilled by Irv

Novick, inked by Frank McLaughlin, coloured by Glynis

Wein, lettered by Ben Oda and edited by Paul Levitz, and

it kicked off and ended all in this one issue. Batman #315

also displays a perfect example of what used to be the

classic comic book splashpage. Used extensively up until

the end of the 1960s, DC (unlike Marvel) still kept this

"introductory page" (which often performed a

similar function as a movie poster and thus almsot served

as "second cover") in some of its titles

throughout the 1970s.

|

| |

Splashpage Batman

#315 (September 1979)

|

|

This type of

splashpage helps to set the mood and

links the story about to be told to the

origin of the Batman - the darkness of

Gotham triggered the existence of Batman,

and now he stalks the city by moonlight

so that Gotham may never forget what its

violence has spawned... Clearly,

this is still the "1970s dark

knight" period of Batman, although

the villain in this issue (Kite-Man) will

hardly send any shivers down the reader's

back - which is in stark contrast to the

gang of villains out to give Batman a

rough time in Batman #1.

Not so much an

indication of a "dark" Batman

but rather of the fact that this is now

generally a "T" rated comic

book.

|

|

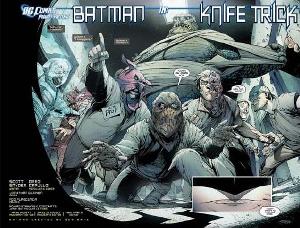

Splash page

double-spread Batman #1

(November 2011)

|

|

|

| |

| The

splashpage from Batman #1 performs an entirely

different function, made clear also by the simple fact

that this double spread covers pages 2 and 3 and not the

first page. And finally, this will be anything but over

by the end of this issue, as this monthly will simply be

the first 32 pages of a trade paperback collecting the

first story arc - and it is this form of publication

which ultimately dictates the length and pacing of the

storyline. In 1979, writing letters to the

editor of a comic book was pretty much the only way

available to readers who wished to make their opinions

heard, and Batman has a long tradition of aptly

named letters pages.

|

| |

|

| |

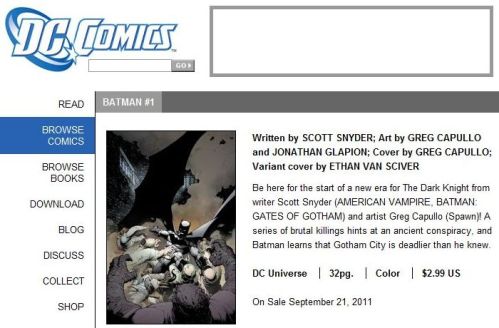

| In

September 1979, you wrote in to Bat Signals, but

whilst the letters page had been revived by DC throughout

most of the monthly titles in late 2010, Batman

along with all other titles of the "New 52"

lost this feature again for good upon relaunch. |

| |

Editorial page from Batman

#315

(September 1979)

|

|

No readers voices therefore

in Batman #1, unlike in Batman

#315, but at least editorial had a voice in both

1979 and 2011. In 1979, the "Daily

Planet" editorial page offered extended

teasers for Super Friends #24 and House

Of Mystery #272, the "Answer Man"

column (which this time around looked into

questions such as what kind of gimmicks were

stowed away in Batman's utility belt or if Wonder

Woman and Green Lantern had ever fought against

each other), a Hembeck cartoon (spoofing the

Spectre and the original Flash), and the

"Direct Currents" overview and

checklist of DC titles on sale the week of June

18th 1979.

This

density of information (and entertainment) is

only just met in Batman #1, even though

editorial content is spread out over three pages

- it would almost seem that the general tendency

towards decompression on the levels of plot and

storytelling have also affected editorial.

|

|

Editorial page "All

Access" from Batman #1 (2011)

|

|

| |

| All three editorial pages in Batman

#1 are concerned with DC's "New 52"

titles and could thus also be seen as being

little more than text-heavy in-house

advertisements. In "DC Comics All

Access" readers are basically offered five

sketches of Wonder Woman for the "New

52" plus a few lines by Art & Design

Director Mark Chiarello which basically plug a

few artists working for some of the "New

52" titles.

The

level of information rises slightly on two pages

of creator interviews, each concerned with the

author and artist of one specific title (in this

case Red Hood and the Outlaws and Blue

Beetle). The teams answer to the same set of

questions, but again - what could potentially be

an interesting comparison leans rather heavily

towards an all-out plug for the "New

52". Overall, readers got more information

on one page in 1979 than they did on three in

2011.

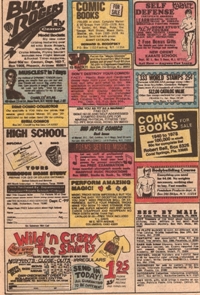

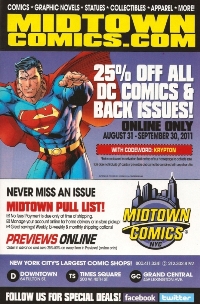

Readers

also got more advertisments in their comic books

back in 1979, although this would of course

hardly rate as a positive with many. In 2011, ads

are all full or even double page, which was

already becoming a predominannt format in 1979,

although half-page ads could also be found whilst

the classic "flea market" ads page from

the 1970s was down to one single page in Batman

#315.

|

|

Editorial page "The New

52" (one of two pictured here) from Batman

#1 (2011)

|

|

| |

Ad page from Batman

#315 (September 1979)

|

|

That specific page

still featured ads for means of building

up muscle and acquiring some sort of high

school diploma, but already ads from

comic book stores selling current and

back issues were appearing. In 2011, one

such company grabbed an entire page to

advertise their services. Possibly

one of the most striking differences

between these two comic books lies - not

surprisingly - in the artwork. However,

these differences illustrate the changes

in technique more than any changes in

artistic style. Whilst these have also

occured, the computer based production

methods really make themselves felt when

looking, for instance, at the colouring.

This is, of course,

further enhanced and accentuated by the

use of higher grade paper by comic book

publishers since the mid-1990s, which has

greatly improved the artwork and colour

rendition.

|

|

Ad page from

Batman #1 (November

2011)

|

|

|

| |

Pencils

by Irv Novick, Inks by Frank McLaughlin, Colours by

Glynis Wein - Batman #315 (September

1979)

|

| |

| Whilst the

printing in Batman #315 cannot be said to be

bad, there is still a certain amount of blurred inking

rendition and colour bleeding. |

| |

Pencils by Greg

Capullo, Inks by Jonathan Glapion, Colours by FCO

Plascencia- Batman #1 (November

2011)

|

|

The current use of high

quality glossy paper, on the other hand, which

has been chemically de-pulped and coated with an

alkaline buffer, produces superb quality

renditions of artwork and colours, and thus does

the efforts of the creative teams justice and

provides a faithful rendition of their work,

whilst the printing from 1979 does have its

limits in that respect. Obviously,

such improvements will be reflected in the price

of a product, and the rise from 40c (or 15p)

needed to purchase Batman #315 in 1979

to the $2.99 it cost anyone wishing to read Batman

#1 in 2011 is a sharp one. This is accentuated

further when taking into consideration that the

purchasing power of 40c for commodities in 1979

equals $1.20 in 2010 when using the consumer

price index; in terms of

"affordability", spending 40c on a

comic in 1979 equals spending an amount of $1.65

in 2010 (measureworth.com).

What

these figures indicate is that today's improved

paper and printing quality comic books are

roughly twice as expensive as they used to be in

1979. But regardless of the differences in their

respective production qualities and selling

price, Batman #315 and Batman

#1 share the similarity of both having been

published during a period of relative gloom for

the comic book industry.

|

|

| |

| In 1979,

the market for comic books shrunk to an all-time low

(Daniels, 1991), and DC still felt the shock of the

abrupt cancellation of around 30 titles (the so-called

"DC Implosion") in September 1978. 2011, on the

other hand, had started out as an especially lean year in

terms of sales, following a string of years which

themselves had seen a constant decrease sales figures. In

February 2011 (according to figures released by Diamond

Distribution) Green Lantern #62 was the best

selling monthly comic book in North America with a mere

71,517 copies, making it the lowest selling number one in

years. It took an exceptional corporate mega-event such

as DC's "New 52", in which Batman #1

plays an important part; only by including this

established title along with the likes of Detective

Comics, Action Comics and Superman

in the general number reset to 1 could DC claim an

all-across-the-board event which would attract the

widespread attention it finally did. Accordingly, sales

figures virtually exploded in comparison to the year's

previous statistics, and Batman #1 became the

best-selling comic book of September 2011 with an

impressive total of 188,420 copies - also giving DC its

first market share victory over Marvel in years. Even though the

"New 52" have helped boost the sales of comic

books in general, this is of course nowhere close to

where sale figures once were. According to the

circulation figures reported to the US Post Office, Batman

comic books sold an average 502,000 copies per month

in 1960, and sales figures even rose to 898,470 copies

per month in 1966 as a result of the popular tv show. The

big slump came in the 1970s, when sales dropped to

293,897 in 1970 and decreased further throughout the

decade. Whilst the sales figures of 1979 (166,640 copies

on average per month) are not too far away from the

188,420 copies sold of Batman #1, their

background could not differ more - the sales figures of

1979 were at the end of a constant decline, whilst the

sales figures of Batman #1 and other "New

52" titles were a rocket blast out of a market

misery.

The constant

decline in sales and profits throughout the 1970s finally

led to the creation of the "direct

market", which is generally credited with having

saved the comic book industry from almost certain death

(Groth, 2006). It created the specialist comic book shop

as the main point of sale ("direct

distribution"), thus streamlining the distribution

system and doing away with the returns system whereby

newsagents could return any unsold copies and get

refunded, i.e. a business model which did nothing to

encourage actual sales (Groth, 2006). The direct market

changed the entire system of comic books, and whilst it

helped to prevent worse, it also meant by definition that

comic books would be mostly "hidden" from the

general buying public.

|

| |

| Therefore, whilst I was able

to buy Batman #315 at a WH Smith store

in 1979, they did not carry Batman #1 in

2011, in spite of the fairly wide public coverage

DC's "New 52" received. However,

this did not mean that anyone eager to pick up a

comic book featuring Batman would need to leave

WH Smith empty handed. Rather surprisingly, there

even was a wider and far more varied choice in

comparison to 1979 (when you could get issue #315

only), with the UK reprint Batman Legends

#49 on sale as well as a wide choice of trade

paperbacks (TPB) featuring the Darknight

Detective, such as Batman: The Black Casebook

(2008) or Batman: The Strange Deaths of Batman

(2008), along with the omnipresent Killing

Joke (various editions since 1988).

Oddly

enough, in terms of Batman, the direct market has

had no influence on the availability of material

at WH Smith's other than the actual US monthly

comic book. No doubt this says a lot about the

iconic status and household name of Batman. And

whilst there could have been no certainty for the

teenage reader who picked up Batman #315

in September 1979 that there would also be a new

issue of Batman on offer in September

2011, somehow it always seemed clear beyond a

doubt that Batman would be around for, well, for

ever.

|

|

UK Batman Legends #49

(September 2011)

|

|

| |

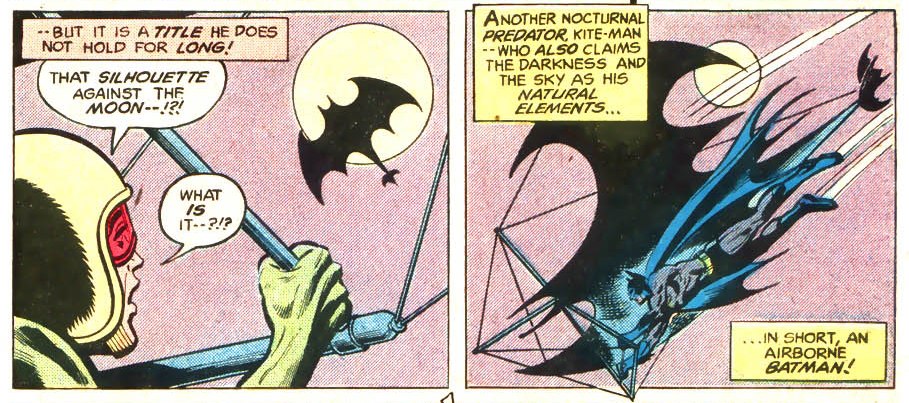

| The last

question to be raised here therefore is - what will Batman

look like after another 32 years? Assuming that DC

will pick up the original numbering again (which stopped

at #715 in August 2011) somewhere down the road, that

would be around issue #1100. And oh, one last

thing - if you thought the "bat glider" used by

Batman in issue #315 to bring down Kite-Man was typical

1970s comic book old-tech... well, think again. And take

a look at this scene from Batman #3 (cover date

January 2012, out in November 2011). There you go - now

that you've read this write-up, you can really put that

scene into perspective.

|

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

DANIELS Les (1991) Marvel:

Five Fabulous Decades of the

World's Greatest Comics, Harry N.

Abrams, Inc.

GROTH Gary (ed.,) (2006) The

Comics Journal #277 (July 2006),

Fantagraphics

|

| |

|

| |

|