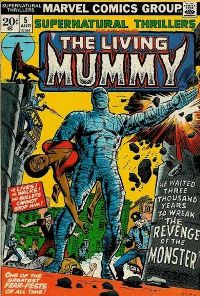

In-house

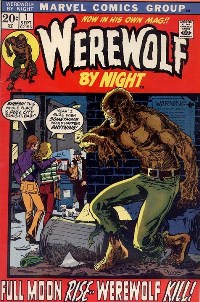

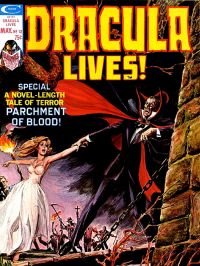

ad for Dracula Lives!

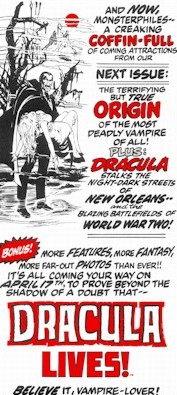

Dracula

Lives! #12 (May 1975)

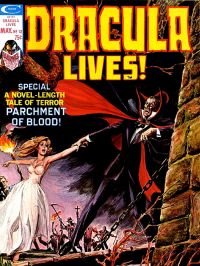

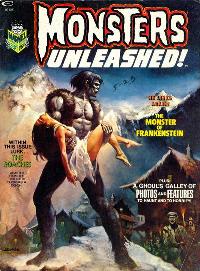

Monsters

Unleashed! #2 (September 1973)

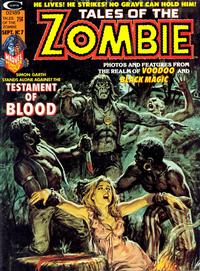

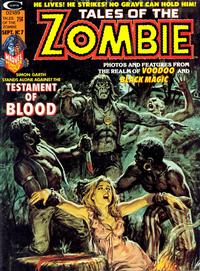

Tales

of the Zombie #7 (September 1974)

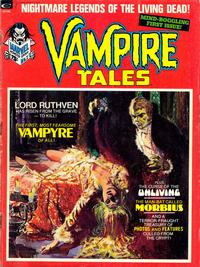

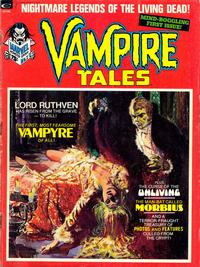

Vampire

Tales #1 (August 1973)

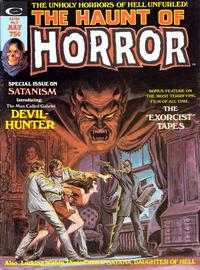

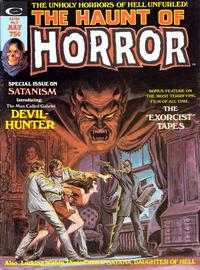

Haunt

of Horror #2 (July 1974)

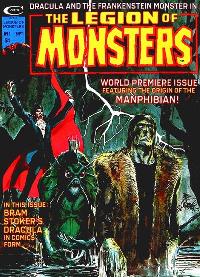

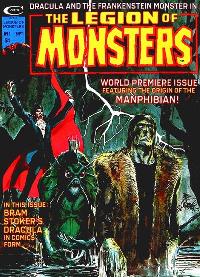

Legion

of Monsters #1 (September 1975)

|

|

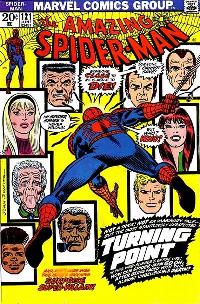

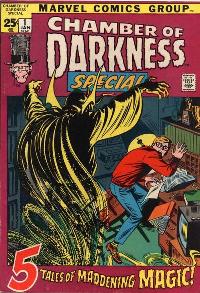

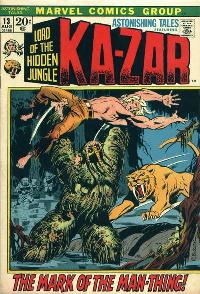

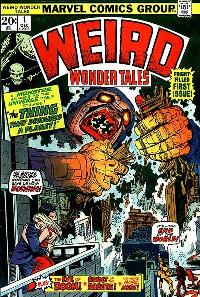

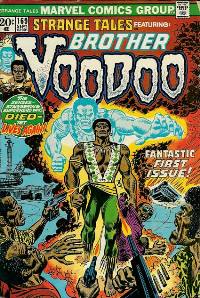

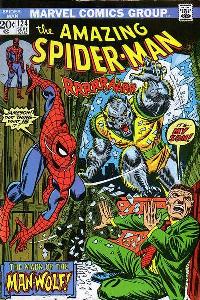

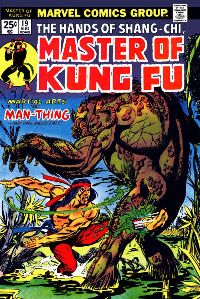

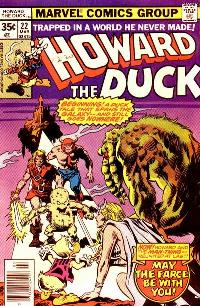

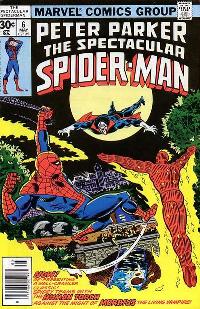

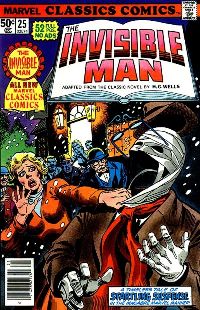

"Can

there be any doubt that the Second Age of Marvel is

upon us in full glorious bloom?" (Marvel

Comics June 1973 Bullpen Bulletin)

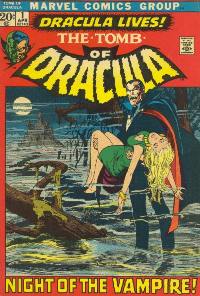

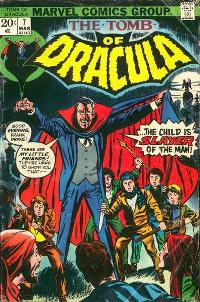

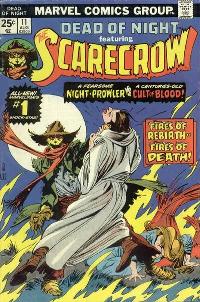

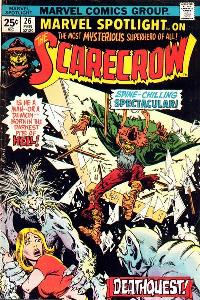

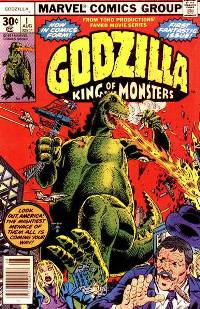

The first

black and white horror magazine to be launched was Dracula

Lives! in June 1973 (with the cover only carrying

the date "1973"). Advertised as a "giant

sized 75c comic" (June 1973 Bullpen Bulletin) Dracula

Lives! #1 in fact only contained 35 pages of new

original material in its total pagination of 72. The

remaining pages were filled with pre-code reprints from

the early 1950s and text-only articles plus photos from

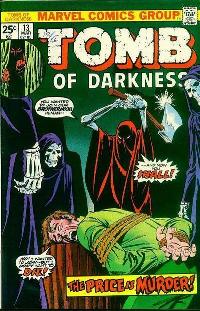

old movies. In order to stay clear of the established Tomb

of Dracula and avoid contradictions with the

storyline of Marvel's most successful horror title, the

material in Dracula Lives! generally stuck to a

different set of time and location.

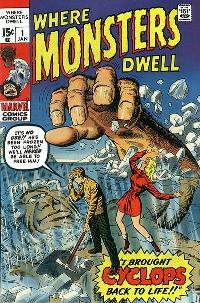

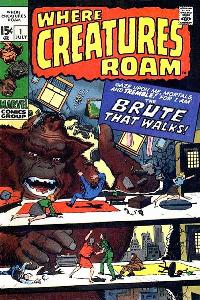

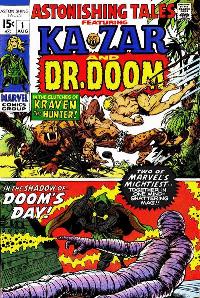

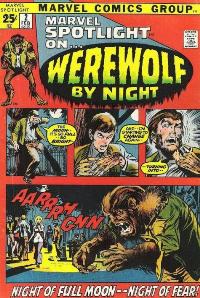

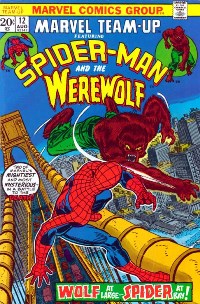

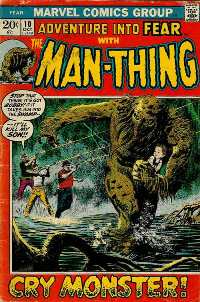

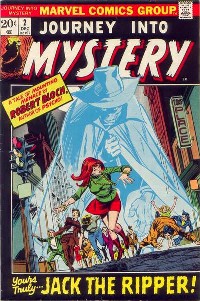

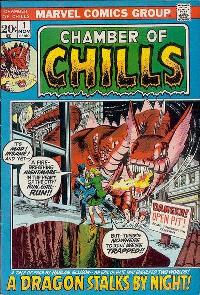

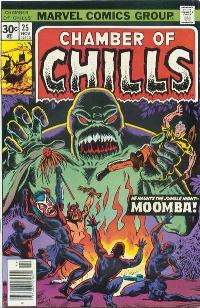

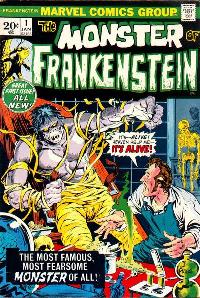

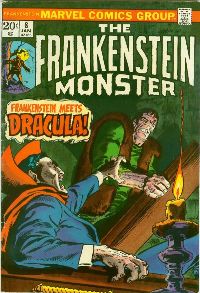

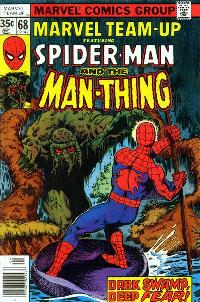

Next in line

was Monsters Unleashed, first published in July

1973, which followed the formula set out by Dracula

Lives! the month before. Whilst the first issue

seemed to indicate that this title would feature

adaptations of literary horror stories in the vein of the

colour titles Journey Into Mystery and Chamber

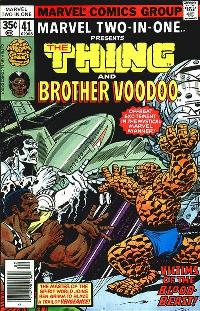

Of Chills, Monsters Unleashed quickly

became just as erratic as many of Marvel's previously

released colour anthology titles. Apart from sword and

sorcery material creeping in - which didn't seem to fit

the magazine's title at all - Marvel decided to feature

black & white versions of some of their horror genre

figures already featuring in colour titles as of issue #2

- most noteably the Frankenstein Monster.

"Beginning

this go-round, [Monsters Unleashed #2] spotlights a

senses-staggering new serial starring THE MONSTER OF

FRANKENSTEIN, picking up where our ever-fabulous

color comic leaves off!" (Marvel

Comics August 1973 Bullpen Bulletin)

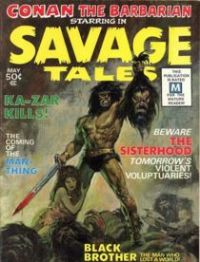

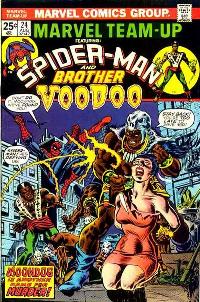

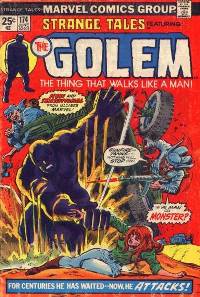

The third

black & white title of this barrage was Tales of

the Zombie. Written by Steve Gerber and very

atmospherically pencilled by John Buscema and inked by

Tom Palmer, the story centering around Simon Garth, a

successful coffee harvester in New Orleans who is turned

into a Zombie by means of voodoo rituals, lived up to

Marvel's definition of "mature" - it was

violent and graphic, and topped with a fair amount of

nudity.

Tales of

the Zombie was unique in that it featured a complete

story arc across the entire ten issues Marvel would

eventually publish. The magazine is, however, even more

noteworthy for the fact that it featured zombies both as

story characters as well as in its title - at a time when

the Comics Code (not applicable to magazines) still had

an outright ban on the walking dead (Nyberg, 1998).

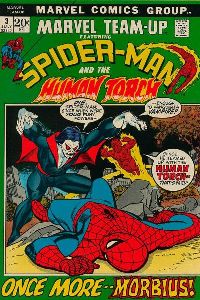

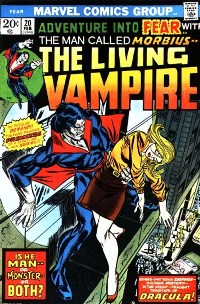

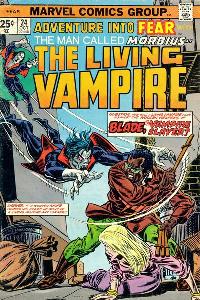

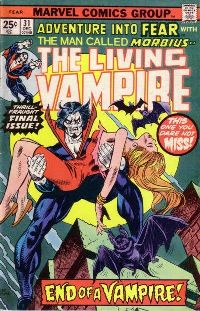

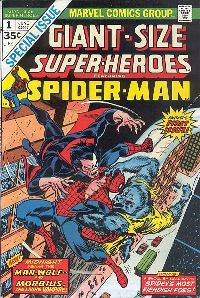

Finally, Vampire

Tales #1 was published in August 1973, featuring an

adaptation by Ron Goulart and Roy Thomas (pencilled by

Win Mortimer) of the short story The Vampyre, published

in 1819 by John Polidori (based on a fragment by

Lord Byron) and the progenitor of the literary vampire of

the romantic period. Issue #2, however, went a completely

different way and featured a reprint of the Morbius

origin sequence from The Amazing Spider-Man #102,

after which he would be featured in his own ongoing

series in Vampire Tales until June 1975.

Marvel's

entry into the black & white horror comic magazine

scene was impressive, but at the end of the day this

all-out assault launched in order to cut into competitor

Warren's niche market had very little effect, as James

Warren himself concluded:

"They

didn't understand what was involved. They weren't set

up at the time like we were; they didn't look at

their artists and writers like we did - they were

production houses with deadlines to meet (...) The

mindset at National and Marvel sometimes regarded

scheduling and deadlines as being more important than

the product (...) It was a half-hearted attempt to

float something to see if it'll sink. It was no way

to launch a new line (...) You saw the content; it

was mediocre. I talked to Stan years later and said,

"You have 'Stan Lee Presents' on these books!

How can you have your name on stuff like this?"

I now realize I was saying the wrong thing because he

was part of a huge company that operated on a

different mindset." (Cooke,

2001)

Different

mindset or not, the black & white market did not

prove a successful venture for Marvel. The titles

launched soldiered on for a couple of issues and were

then quietly dropped from production, despite the fact

that, unlike the many promising colour anthology titles,

Marvel provided the black & white magazine line with

stable editorship and that the man in charge, Marv

Wolfman, had even worked for Warren prior to signing on

at Marvel (Cooke, 2001).

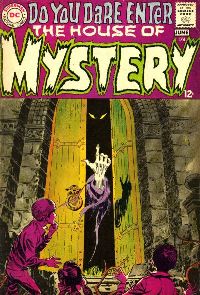

The problem

was elsewhere. Warren was the established black &

white comic magazine market leader, so Marvel had to

compete with established publications such as Vampirella.

Luring readers away from these would be extremely

difficult at the outset, so Marvel needed to build a

market position through new readership. The House of

Ideas, however, couldn't have picked a more adverse time

for this, as the US economy and the US dollar went into

the worst slump since the 1970 recession and consumers,

stunned by higher prices, were spending less and less

(NN, 1973).

Unable

to escape the general market situation, Marvel even had

to increase the cover prices of their established colour

comic books in early 1974, communicated through their

June 1974 cover date letters pages. This was

the worst possible setting for the black & white

comic magazines, as the established readership already

needed to pay more just to continue buying their regular

comic books before even thinking about something new, and

together with content which was hardly ever a "must

buy", it eventually broke the neck of Marvel's

venture into the black & white comic magazine market.

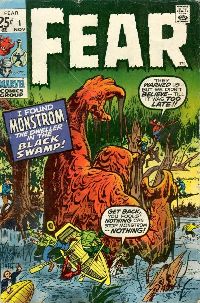

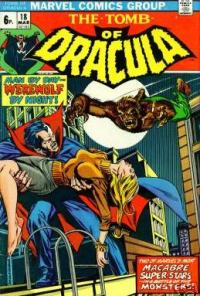

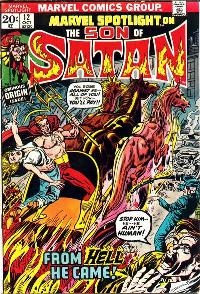

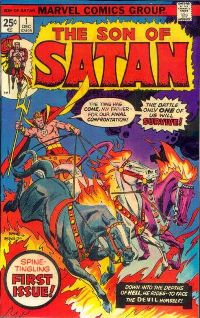

Marvel

did make one final attempt in April 1974 with the launch

of Haunt of Horror under the editorship of Roy

Thomas and Marv Wolfman. Starting with issue #2 the

magazine became the home of "Gabriel

Devil-Hunter", Marvel's answer to the splash created

by the movie The Exorcist in 1973. Written by

Doug Moench and pencilled by a number of constantly

changing artists,

Gabriel seemed to derive much of his appearance from Nick

Fury with his eyepatch and firm jaw. As for content, the

quality was very poor - or, in the words of Tony Isabella

(editor for issues #3 and #4):

"The

lead feature - Gabriel Devil-Hunter - was this

blatant attempt to cash in on the success of The

Exorcist. It was awful stuff and a real pain in the

butt to produce (...) Marv was milking The Exorcist

for all he could (...) Editing "Haunt Of

Horror" was not my finest hour, but sometimes

you have to take one for the team." (K, 2005)

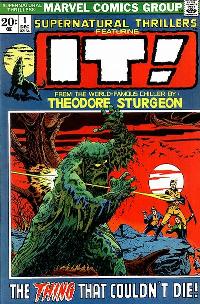

Haunt

of Horror lasted for five issues before cancellation

in January 1975, and the helter skelter publication dates

(ranging from monthly to tri-monthly) really speak for

themselves. Marvel finally quit trying for the black

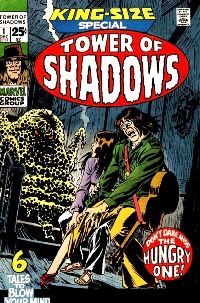

& white market with original material. Masters of

Terror, launched in May 1975, was an all-reprint

b&w magazine featuring stories previously published

in their colour anthology books such as Supernatural

Thrillers or Tower of Shadows, but this

only lasted for a mere two issues.

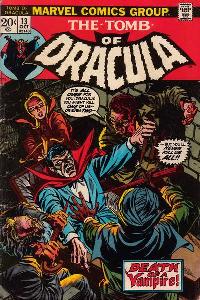

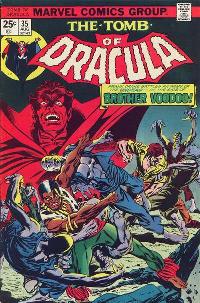

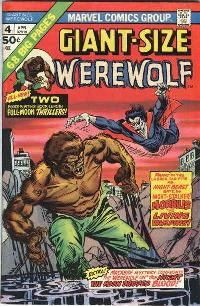

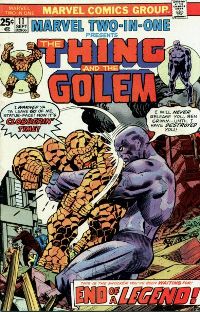

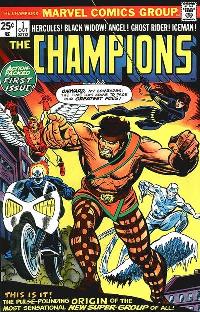

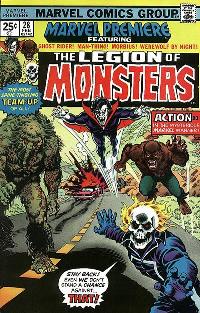

The

headliners of the various cancelled b&w magazines

were regrouped in September 1975 in Legion of

Monsters #1 - which would remain the only issue

published. For the rest of the Bronze Age period,

Marvel's less than successful venture into the b&w

magazine market finally came to a grinding halt until

October 1979, when Tomb of Dracula would be

transferred from the colour format to the b&w

magazine of the same title - again, with little success.

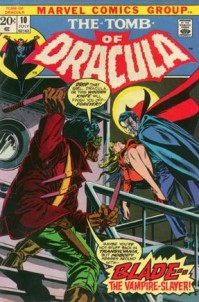

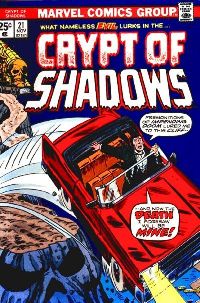

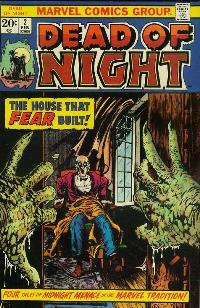

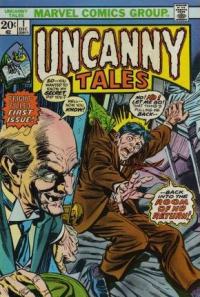

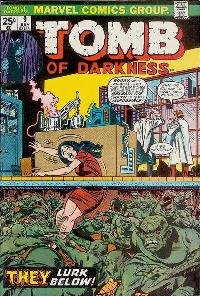

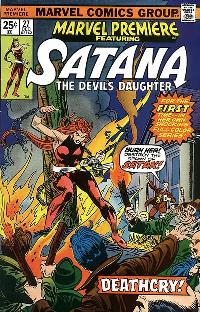

Marvel's

1973 barrage of black and white magazines was an attempt

to ride on a wave of "mature content" which

very quickly became based on nothing more than cliches

which were amplified through covers which too often were

repetitive, unimaginative and - to a certain degree -

even crude.

|