A VAMPIRE STALKS THE NIGHT ! |

||||

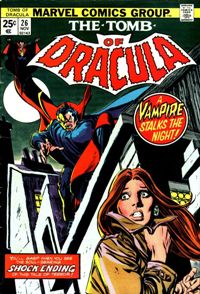

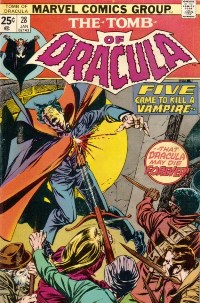

SPOTLIGHT ON THE TOMB OF DRACULA #26 |

||||

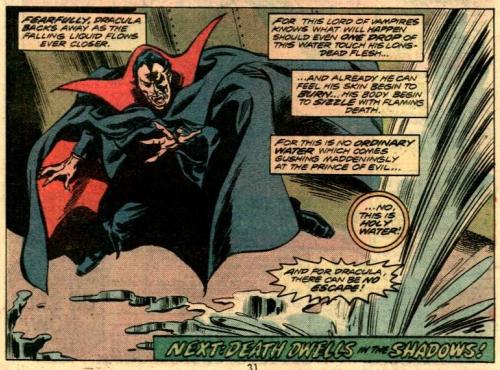

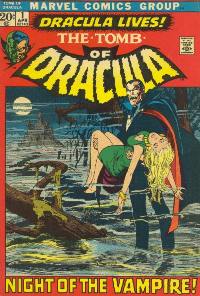

| As Marvel's most popular and successful ongoing horror title of the 1970s, Tomb of Dracula weaved an ongoing saga plotting the lord of vampires against a group of vampire hunters which was vividly brought to life by Marv Wolfman's gripping storytelling, Gene Colan's dramatic pencils, and Tom Palmer's intense inks. The overall result was a gothic atmosphere which harked back at the classic vampire stories while at the same time adding new momentum to the theme, making Tomb of Dracula Marvel's outstanding contribution to the genre and a classic in its own right. Amongst the 70 issues published from April 1972 through to August 1979, some stand out as exceptionally well produced examples of the comic book medium - such as Tomb of Dracula #26. | ||||

|

||||

SYNOPSIS - TOMB OF DRACULA #26 IN CONTEXT - REVIEW AND ANALYSIS - WHERE TO READ IT |

||||

|

||||

| SYNOPSIS | ||||

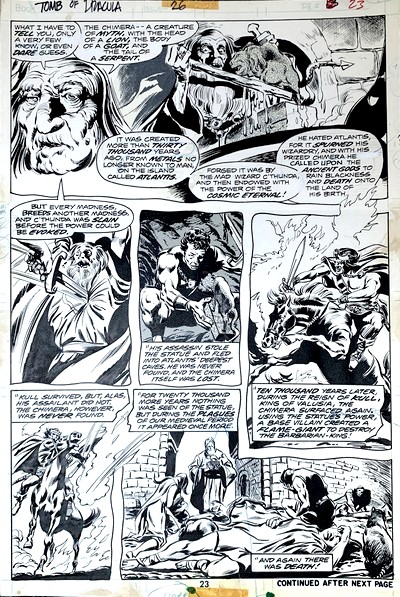

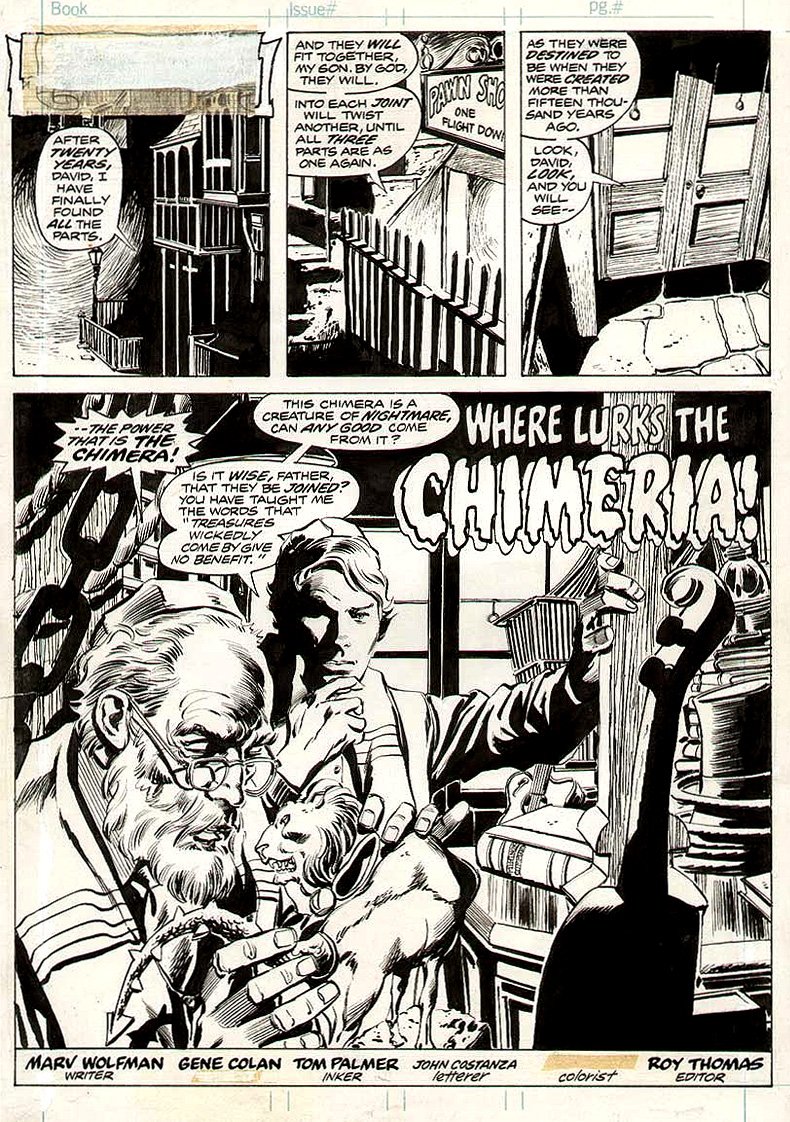

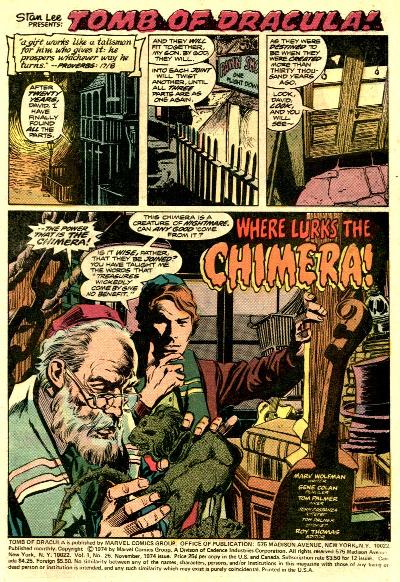

| Tomb of Dracula #26

features the first part of a

three issue story arc centering around a

mythical artefact called the Chimera. "A gift works like a talisman for him who gives it: he prospers whichever way he turns." (Proverbs 17:8) |

||||