| |

| In the real

world, time travel is no problem to speak of - as long as

you're headed into the future, that is. On a theoretical

level, the concept is a fundamental aspect of Einstein's

theory of relativity, and on a practical level we all

know that time does not stand still and we will therefore

find ourselves in the future (for example tomorrow).

Essentially, it's just the speed of our trip to the

future which raises questions. Someone travelling aboard

a space rocket at near light speed, for example, would

find that one year's travel onboard equals 223 years for

folks back at the launchsite on Earth (Davies, 2003).

That's not part of our real world experience only because

we have neither the technology nor the energy at our

disposal to travel at near speed of light. No, the really tricky

aspect of time travelling only kicks in when you're

thinking of going back in time. Now there's

nothing in Einstein's theory that precludes this per se,

but a huge stumbling block lies with the fact that even

just going back to yesterday violates the law of

causality, i.e. the balance of cause and effect, which

runs through the entire universe - whenever something

happens, this leads to something else, and so on and so

on. It is an endless and - most importantly - one-way

string of events as the cause always occurs before the

effect. This defines our reality, and although other

realities are in theory conceivable (e.g. where the

thunder precedes the lightning), the basic laws of

physics in such a reality would utterly violate reality

as we know it. This is the prime reason why many

scientists quite simply dismiss time travel into the past

as an impossibility (Davies, 2003), whilst others feel it

could only happen within certain strict limitations

(Sanders, 2010).

Even on a

purely theoretical level, time travel is a tricky

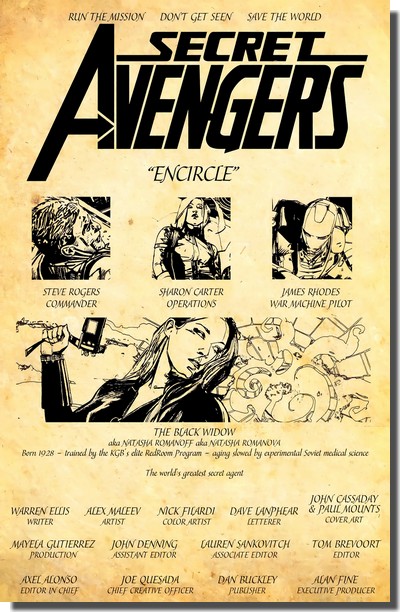

subject, but with Secret Avengers #20 readers

quickly realize that Warren Ellis has done all of his

homework in all of the relevant fields.

|

| |

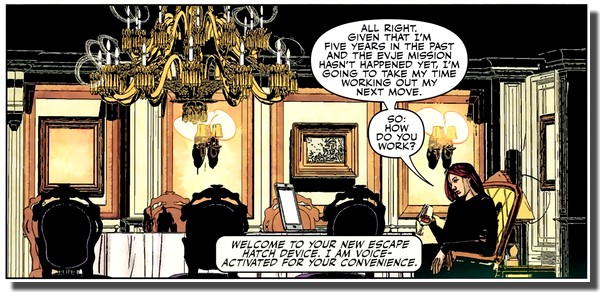

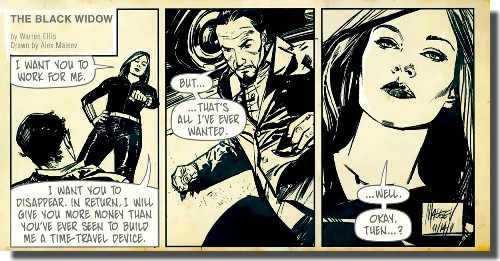

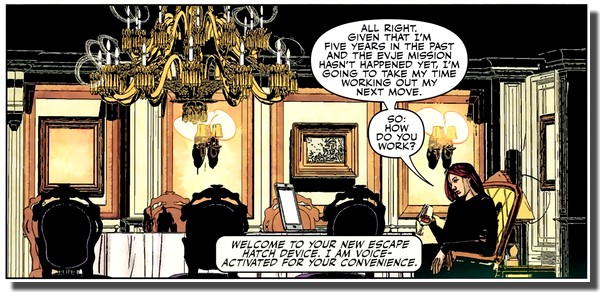

| After activating the Escape

Hatch device, the Black Widow finds herself

transported five years back in time and to the

stately Villa Vedova (which, in Italian, is

"widow") near Trieste (Italy). However, she

also realizes that she knows little to nothing

about time travel - not the least because she

never listened to fellow Secret Avenger and

bright scientist Henry McCoy (a.k.a. The Beast)

talk about it.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Deciding to

proceed with caution, she takes time to fully familiarize

herself with the device, and it is here that Natasha Romanova (who

has her own personal experience with time as she was born

in 1928 but ages slowly due to having been treated with

secret Soviet medical technology) learns the most

important rule of time travel - the timeflow must be

preserved. |

| |

|

|

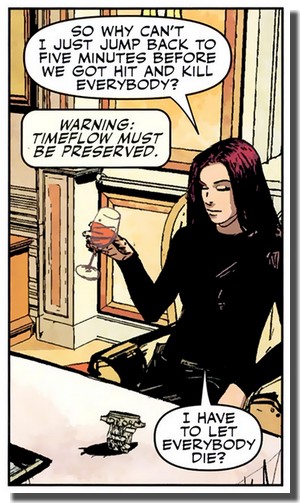

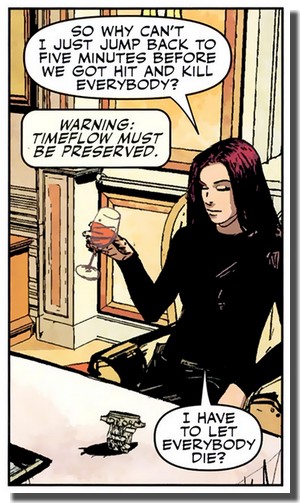

By having the device

programmed with a few instructional messages for

the Black Widow, writer Warren Ellis also sets

things straight for the reader in a nifty way -

six pages into the story we are now all made

aware of the fact that time travel is not easy

and requires some advance thinking - because you

must avoid creating a paradox in time. This is why

Natasha Romanova can't, as she herself suggests,

simply resolve the situation five minutes before

it happens - not the least because this would

create the paradox of eliminating the reason why

she travelled back in time in the first place.

In

fact, the possibility of creating such paradoxes

in time has led a number of physicists to

conclude that time travel is not possible.

Stephen Hawking, for example, stipulated the chronology

protection conjecture which holds that the

laws of physics are such that they not only

disallow but actually prevent time travel on all

but sub-microscopic scales (Hawking, 1992) - but

he also put forward other arguments:

"So

it might seem possible that, as we advance in

science and technology, we might be able to

(...) travel into our past. If this were the

case, it would raise a whole host of

questions and problems. One of these is, if

sometime in the future we learn to travel in

time, why hasn't someone come back from the

future to tell us how to do it."

(Hawking, A.N.)

|

|

| |

| The answer

to that somewhat tongue in cheek question might be:

because time travellers not only avoid creating paradoxes

- they are unable to. This, in essence, is the conclusion

of the Novikov self-consistency principle

developed by Russian physicist Igor Dmitriyevich Novikov

in the mid-1980s to solve the problem of paradoxes

arising out of time travel (Friedman et al., 1990). The

Novikov Principle does not allow a time traveller to

fundamentally change the past in any way (and thus

create a paradox), but it does allow the time traveller

to affect past events in ways that produce no

inconsistencies - meaning that an event affected by a

time traveller will always and throughout history be an

event affected by a time traveller, so that there will be

no alternate "before and after" version to an

"original history". Or, as Sanders (2010)

phrased it in the title of an article she wrote for Science

News: "Physicists tame time travel by

forbidding you to kill your grandfather". Quite obviously you

can follow the story of Secret Avengers #20

without needing to know any of this, as Warren Ellis

mounts the suspense and intrigue of his plot by sending

the Black Widow on a mission through time with the

premise "you can't change what happened - but can

you affect and tweak it in a way which will prevent the

Secret Avengers from dying in that attack in

Norway?" She may not know it, but as of now Natasha

Romanova's moves are guided and defined by the Novikov

self-consistency principle.

And so the

Black Widow embarks on a criss-cross journey through time

and around the world in order to gain required

information and affect events in such a way that they

allow her to get ever closer to the purpose of all these

efforts - save her fellow Secret Avengers from dying in

battle against the Shadow Council in Norway. Naturally -

as we would all expect from a comic book - the heroes

ultimately do survive, but the way Warren Ellis pulls

this off is both entertaining and fascinating, just as

his overall storytelling remains consistent and coherent.

And yes,

throughout the Black Widow's quest the Novikov

self-consistency principle is observed at all times as

Warren Ellis fuses an all-out spy story with serious

physics in an impeccable and elegant way as the reader

notices that certain events in the past - which thus

happened before the fatal Norway incident anyway - are

actually tied to the Black Widow's time travels. Ellis is

completely spot on as he weaves his compelling story

without creating a single unresolved time paradox.

|

| |

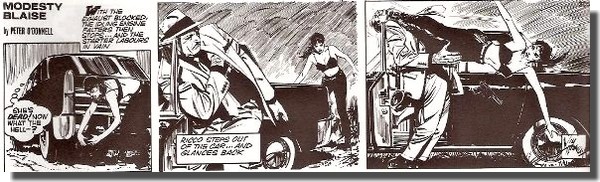

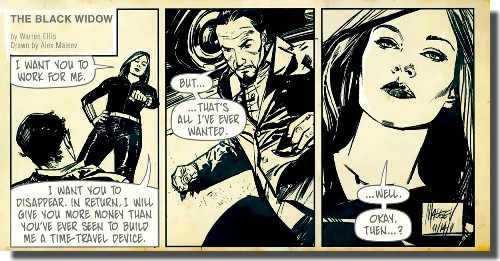

| This is certainly no mean

feat for a 20 pages story in a "done in

one" comic book, and what could easily have

become either a simplistic or overly complicated

affair works flawlessly. The non-linear

storytelling is paced just right and cleverly,

but always easy to follow thanks to clear markers

where and at what point in time an event actually

takes place. The result is a superhero-scifi-spy

tale which satisfies the intellect as much as the

expectations for suspense and action. To make

things near perfect, the visuals of Secret

Avengers #20 by Alex Maleev fit this

extraordinary story like a glove as he provides

an interesting mixture of realism and mysterious

intrigue, creating an atmosphere which draws the

reader right into the story. And there's even

more - in a cameolike yet perfect setup Maleev

also pays hommage to the archetypical comic strip

spy, Modesty Blaise, and her creators, Peter

O'Donnell and Jim Holdaway, as the style of his

artwork changes to vintage newspaper strip format

as the Black Widow travels back to approximately

the time in which Modesty Blaise held sway.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| This might be the one part of

Secret Avengers #20 which could leave

some readers slightly puzzled what this is all

about, but the six "newspaper strip"

format inserts will not come across as stumbling

blocks for the rest of the story. For those in

the know, however, this is a nice touch of extra

class and a tip from Maleev's hat in the

direction of what must certainly have been one of

the major influences in the creation of the Black

Widow back in April 1964 for Tales of

Suspense #52.

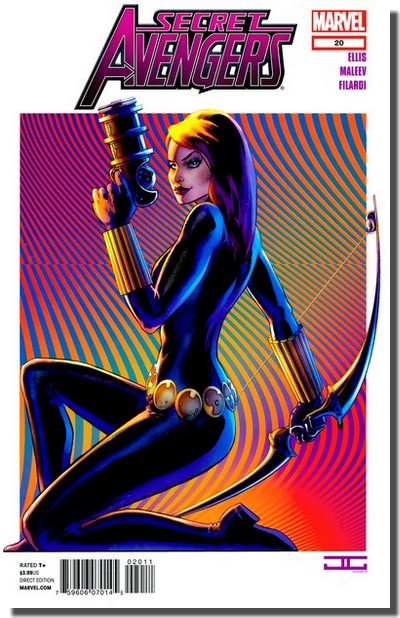

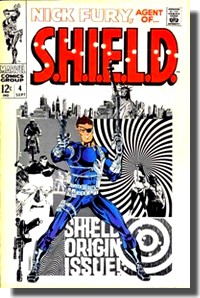

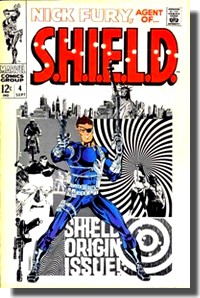

And

there are even more references to comic book

history as John Cassaday's cover for Secret

Avengers #20 clearly pays hommage to Jim

Steranko's ground-breaking cover for Nick

Fury Agent of S.H.I.E.L.D. #4 (September

1968).

|

|

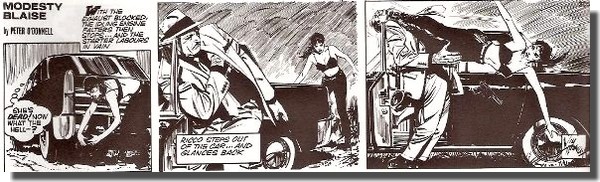

The Modesty Blaise newspaper

strip by Peter O'Donnell (above) as paid hommage

to by Alex Maleev (below) [click for larger

images]

|

| |

|

|

|

| The only quibbles which some

die-hard Marvelites might have is that time

travel as depicted in Secret Avengers

#20 is not truly in line with the canonical

definition of time travel in the Marvel Universe

- where travelling through time always involves

dimensional travel and thus means travelling to

an alternate reality or creating a new alternate

reality. This effectively does away

with any time paradoxes by definition (as these

are only possible in single timeline universes),

and is actually very close to Quantum Theory,

which stipulates that the universe doesn't have

just one unique single history but instead has

every single possible history, each with its own

probability - and whilst this does make Marvel's

approach to time travel appear to be pretty close

to sound scientific concepts, it would not have

worked with this story.

The

fact that Warren Ellis - who is also known for

his passionate arguments for space travel - got

away with it would suggest that editorial at

Marvel considers Secret Avengers to be

something of a fringe title, meaning that what

gets published there causes few if any

repercussions for the Marvel Universe at large.

In that respect, it's a case of history repeating

itself rather than something to do with time

travel:

|

|

Nick Fury Agent of SHIELD

#4

(September 1968)

|

|

| |

"It

was very possible for us to do those things (...)

because no one was paying attention. So Roy Thomas

could do that on Conan, Steve [Englehart] could do

that on Doc Strange and Master of Kung-Fu, [Steve]

Gerber could do it on Man-Thing or Howard the Duck,

and I [Marv Wolfman] could do it on Dracula - and

those were the books that I think made the Seventies

at Marvel something more than just more of the same

(...) [The idea was] to try and push comics into

other things, other areas, that they had not

explored." (Marv Wolfman in Siuntres, 2006)

|

| |

| Comic book history of

course tells us that whilst editorial at Marvel wasn't

paying attention, readers were, and all the books

mentioned by Wolfman did reasonably well for a while and

also received critical acclaim. Secret Avengers

#20 took 47th place on Diamond's Top 300 comic

book sales chart with 38,200 copies for North America in

December 2011 [3], which placed it well in the shadow

of that month's top-selling Justice League #4

with 142,200 sold copies but also enabled it to, as

Wolfman had put it, "push comics into other

things, other areas, that they had not explored." Now of

course time travel has been explored extensively in

comics, but very few have gotten it right the way Warren

Ellis has for Secret Avengers #20 - which is

also, to a certain extent, ironic because just as

impressively as Ellis has succeeded at giving readers a

really good time travel comic book, his fellow British

writer colleague Grant Morrison had failed not only

completely but actually quite miserably on the same topic

in 2011 with his five issue drag The Return of Bruce

Wayne.

Secret

Avengers #20 is, above all, a nifty little

done-in-one comic book. If you are looking for a really

good comic to give to someone who has no idea of the

medium as it works today - Secret Avengers #20

would be an excellent choice. For those already into

comics, it is quite simply highly recommended.

|

| |

#20

#20