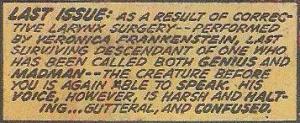

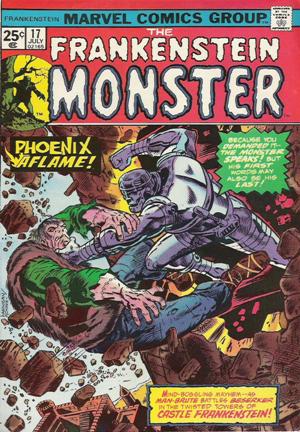

Frankenstein Monster #17

(July 1975)

|

|

Upon

arrival of the trio, the benevolent Veronica

Frankenstein, who hired Prawn to find the

Monster, then performed surgery on its damaged

larynx amidst an ongoing attack from I.C.O.N. -

"International Crime Organization

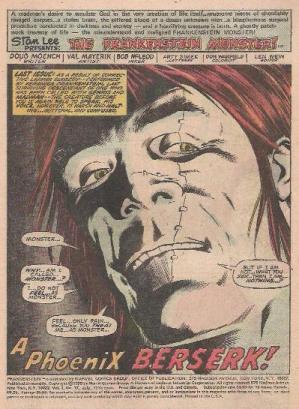

Nexus". Frankenstein Monster #17 opens with a

recap regardingt the Monster's restored ability

to speak and how this came about in the previous

issue.

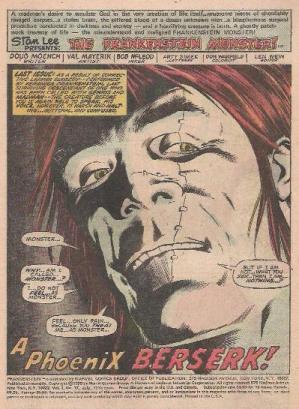

The first words uttered by

the Monster reveal the topic foremost on its mind

- the question of its identity:

"Monster...

why... am I called... Monster? I... do not

feel... as Monster... feel... only pain...

because you treat me... as Monster... but if

I am not... what you say... then I am...

nothing?"

Partly a reaction to having

been called a hero by Caccone for bringing down

I.C.O.N.'s prime weapon, an android called

"Berserker", at the end of the previous

issue, the Monster is evidently both highly

preoccupied and confused, as it concludes with a

logic as sharp as a cold knife:

"And... if I am

nothing... then I should not be here... or

alive."

|

|

| |

| Although

Prawn and Caccone are both surprised and somewhat

overwhelmed by the directness and the weight of the

Monster's first utterances, they both assure the Monster

that it has both a right to live and indeed a place in

life - not the least, as Caccone points out, thanks to

having saved their lives by short-circuiting the

Berserker when he attacked the group. This, however,

provokes more ponderings on behalf of the Monster as it

feels that it has actually killed the android and wonders

whether in fact killing is its purpose and the true

reason for its life. Currently unnoticed, the

I.C.O.N. helicopter carrying agents "Indigo"

and "Cardinal" - who coordinated the previous

attack - is still circling the Frankenstein residence

(which is referred to as a "chalet" but whose

structure resembles a castle more than anything else),

and the two codename operatives are heatedly debating the

options following the deactiviation of the Berserker.

Upon contacting "Rainbow", the head of

I.C.O.N., they receive instructions to contact the

organisation's undercover man inside the Frankenstein

residence, Werner Schmidt, and have him repair the

android.

Meanwhile,

Schmidt tries to secure his cover with Veronica

Frankenstein and the guests by explainig his absence

during the first wave of attacks on the residence (when

he was, in fact, aiding the incoming I.C.O.N. fighters)

with a story of having been trapped and unarmed. Veronica

is beginning to have some doubts but decides to postpone

any further discussions - including notification of the

local authorities - to later on.

|

| |

| Left behind alone in the

laboratory, Schmidt ponders the motionless

Berserker stretched out on the floor when he

becomes aware of flashes of light coming through

the window from the outside and realizes that

Indigo and Cardinal are contacting him by means

of Morse code from the hovering helicopter.

Schmidt replies using a scalpel to reflect the

sunlight and thus quickly receives and confirms

his orders and immediately sets to work. Elsewhere

in the isolated building, Veronica Frankenstein,

Caccone, Prawn and the Monster have obviously

continued the discussion on the topic of identity

and have now reached the question of where Victor

Frankenstein procured the brain for his creation.

The Monster seems determined to find out, but

Caccone cautions its hopes by pointing out that

the Monster obviously cannot recall any details

from the brain's "previous life", not

even a name. The discussion is, however, rendered

academic by Veronica's statement that she has

searched all remaining files and documents of

Victor Frankenstein, including his personal

diary, without finding the slightest hint.

|

|

|

|

| |

| In

fact, it even seems that all information on her

ancestor's work on the Monster seems to have vanished

completely. Veronica Frankenstein deplores the fact that

she cannot offer any real help to the Monster's quest for

its identity but offers empathy and consolation instead. |

| |

|

|

The Monster, however, is

enraged; it seeks help, not pity, and as there

seems to be no hope nor chance for help from this

group of people, the Monster leaves and wanders

out into the snow covered Swiss Alps. Caccone

storms out in pursuit, intending to stop the

Monster and have it turn back, but is brushed

aside and realizes not only that he has no means

of standing in the way of the Monster but also

that there would be no purpose in doing so for,

as he tells Prawn, the Monster is simply mad at a

world that just won't listen.

|

|

| |

| As

the snow continues to fall, the Monster just keeps on

walking and stumbles out into the wide and glaring

whiteness of the Swiss Alps, all the while troubled by

the thought of its true nature. If, as Caccone and the

others have clearly stated, he is no Monster - then just

exactly who is he? Back in the fortified

Frankenstein residence, Schmidt is approaching the final

working steps in his attempt to reactivate the Berserker,

whilst Veronica Frankenstein, Caccone and Prawn are

deliberating whether or not to go after the Monster.

|

| |

| The increasing snowfall,

however, poses a problem, and finally Veronica

suggests to wait a little longer in the hope that

the Monster will return by itself and otherwise

to organise a search party later on, lead by

Schmidt. However, the I.C.O.N. agent

inside the solitary building is preoccupied with

entirely different things at that very moment, as

he signals to the helicopter that he has done all

that he could to restore the Berserker's

functionality again - and that he fears that his

cover will be blown if the android should indeed

become operational again. Cardinal and Indigo

agree to pick him up without delay, and as

Schmidt makes a run for it, the Berserker comes

back to life and starts to search the building in

order to meet his sole objective: capture the

Frankenstein Monster...

|

|

|

|

| |

| The android

quickly runs into Veromica Frankenstein, Caccone and

Prawn. As the latter puts up a short and utterly futile

resistance by firing at the Berserker, Caccone is quick

to inform the metal behemoth that the Monster is no

longer with them and has ventured out into the snow. As

the Berserker turns to follow, the I.C.O.N. helicopter is

by now running low on fuel and will need to return to

base - leaving the android to home in on his target as

programmed... |

| |

|

|

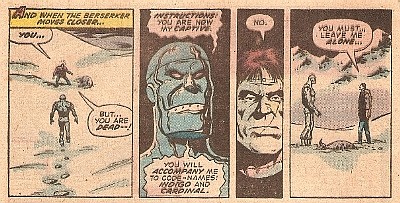

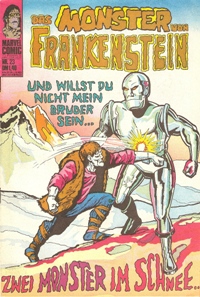

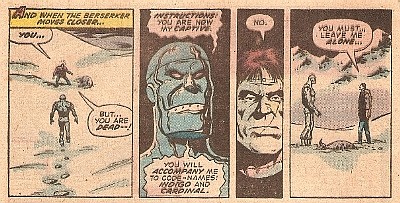

Meanwhile, the Monster has

detected the body of a dead mountain cow, already

frozen for a long time and partly covered by the

drifting snow, and the sight makes the Monster

ponder and reflect upon such things as death for

a lenghty period of time - enough for the

Berserker to catch up with his target. As the two

towering figures - one flesh and bone, the other

all metal and wires - see eye to eye, the android

orders the Monster to accompany him to the

I.C.O.N. base. The Monster, however, has no

intentions of following these instructions, and a

fierce fight breaks out, fuelled by growing rage

on one side and the cool precision of a machine

on the other. |

|

| |

| However,

the onslaught is brought to an abrupt halt when the

Monster rips off one of the android's arms and, feeling a

surge of sympathy for his "injured" opponent,

ceases to lash out at the Berserker and voices concern

about the damage he has inflicted. |

| |

| This outpouring of empathy by

the Monster and simple key words like "pain"

and "life" cause the

Berserker's programming to crash, and the android

too becomes peaceful and begins to gain self

control over his actions - or, as I.C.O.N.

operative Indigo, who is monitoring the events,

concludes with growing concern: the shock of the

inflicted damage on the electronic circuits must

have restored the self-will of the human mind

entrapped in the metal casing of the Berserker... |

|

|

|

| |

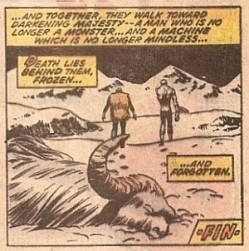

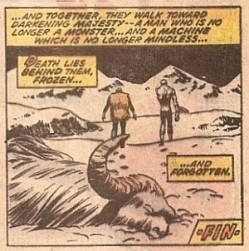

| The

end result is two bewildered behemoths, uncertain about

their future just as they are uncertain about their place

in this world, walking off together into the wilderness

of the foothills of the Swiss Alps. More information on the entire series

is available here:

Marvel's

Monster Mash: Marvel's Bronze Age struggle with the

Frankenstein Monster

|

| |

| FRANKENSTEIN MONSTER

#17 IN CONTEXT |

| |

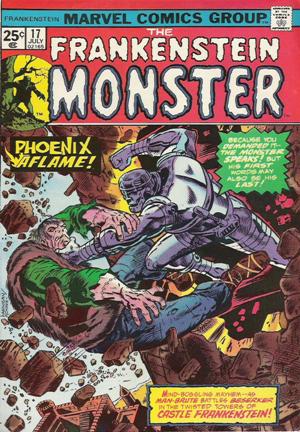

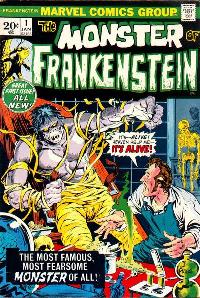

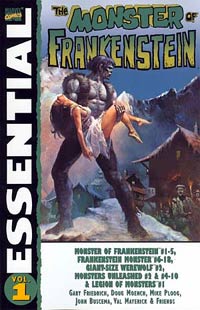

| When Frankenstein

Monster #17 went on sale in April 1975 with a cover

date of July 1975, it was a comic book which in some ways

echoed Kipling's The Last of the Light Brigade,

for here was one of Marvel's horror genre titles which

had started out with acclaim and applause but then found

itself virtually starving whilst still hoping for a "to

be continued" as it hovered on the brink of

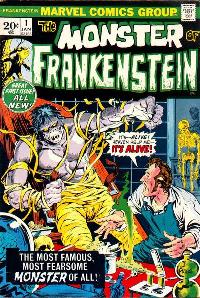

cancellation. Born of the large scale return of the

horror genre to comic books in the early 1970s, The

Frankenstein Monster was set up by Marvel to follow

in the footsteps of their two highly successful classic

horror adaptations Tomb of Dracula and Werewolf

by Night.

|

| |

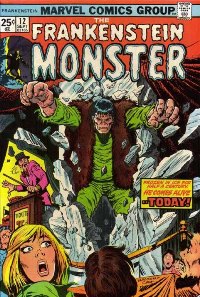

Monster of Frankenstein

#1 (January 1973)

|

|

Although conceived as another

"superhero

from the crypt",

i.e. taking established characters from the

horror genre and making them the protagonists of

their own ongoing titles, the Frankenstein

Monster was to start off on a distinctly

different route than Werewolf by Night

(which took the general mythology surrounding

werewolves only as a backbone for an otherwise

completely new plot and characters) and Tomb

of Dracula (where Bram Stoker's literary

heritage was acknowledged through the presence of

characters from the novel but the general plot

was rooted in the present timeframe and thus

clearly detached from the literary source). This

time, editor-in-chief Roy Thomas

insisted that the title should start

out with an adaptation of the literary source

(Cooke, 2001), and the first four issues of The

Monster of Frankenstein (as the series was

originally titled) thus presented what turned out

to be one of the most faithful renditions of Mary

Shelley's novel in 20th century popular culture. But what

looked like an excellent start for the title very

quickly turned out to be a huge burden. First

off, the successful adaptation put assigned

writer Gary Friedrich and artist Mike Ploog in a

position of having to literally continue Mary

Shelley's novel - a very tall order even for an

experienced comic book author such as Friedrich,

who was 30 at the time and had just co-created

Ghost Rider a few months earlier.

|

|

| |

| Ironically,

the second fundamental problem of the series was the

result of Friedrich's attempt to fix the first dilemma

and come up with a sensible sequel to the literary source

material. Friedrich connected the original comic book

plot to the end of the novel (where the monster bids

farewell to the explorer Sir Robert Walton somewhere in

the vast emptiness of the Arctic Sea and then drifts out

of sight) by choosing the same locale and introducing

readers to the explorer's great-grandson, Robert Walton

IV who has just found the Monster frozen in a block of

ice. With this framework for the adaptation (as Walton IV

retells the classic tale from Shelley’s novel to a

young midshipman) Friedrich opted for a period timeframe

and chose the year 1898. Whilst this was fine for the

adaptation, it quickly proved to be a dead end for

Friedrich and Ploog (who also did some plotting) as they

struggled to find a truly working concept for the

monster's story beyond the novel. The range of late

19th century original storyline options simply turned out

to be extremely limited, and Frankenstein Monster almost

immediately became a highly unbalanced comic book stuck

in a completely alien time frame for Marvel and devoid of

any clear storytelling direction.

|

| |

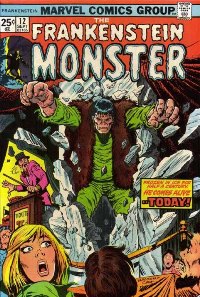

| Caught in a downward spiral,

Friedrich and editorial began to move away

sharply from Shelley's characterization of the

Monster and depicted Frankenstein's creation as a

violent and mindless brute which even lost its

ability to speak after a fight with a vampire

damaged its vocal chords. Friedrich had thus

turned the Monster into what Boris Karloff had

called an "oafish prop"

(Jones, 1995) when he had to play a mute

Monster in Universal's 1939 movie Son of

Frankenstein and thereafter quit the role

because he felt that such a degraded monster left

little room for development. In a last

attempt to salvage the series, Marvel had called

in Doug Moench (26 at the time and the main

author for Marvel's black and white magazines) to

replace Friedrich as of the September 1974

production of Frankenstein Monster #12.

The idea was to transfer the Monster from 1898 to

the present day timeframe, and Moench

accomplished the task in a no-fuss way which

worked well with the artwork from the also newly

assigned penciller, 24-year old Val Mayerik. By

the time issue #17 rolled around, Moench had

fixed the title's most troubling weaknesses by

introducing and establishing a regular supporting

cast, setting up sorely needed

story interest through a mysterious "bad guy

organisation" called I.C.O.N. (International

Crime Organization Nexus),

turning up the overall plot speed, and adding

more background credibility as he sent the

Monster back from NYC to the Swiss Alps.

|

|

Monster of Frankenstein

#12 (September 1974)

|

|

| |

| The

resulting story arc in Frankenstein Monster #16-17

was undoubtedly the strongest of the title's run, but

Moench and Mayerik were up against a problem rooted in

the title's past which virtually precluded securing a

successful continuation - the pronounced and deep

division among its readership with regard to the title's

timeframe setting. |

| |

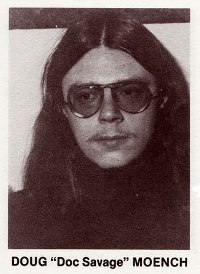

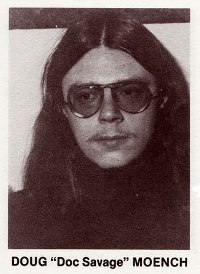

Doug Moench in an official

1975 Marvel picture

|

|

According to Marvel's own

analysis, the 1970s setting found pronounced

approval with two thirds of the readers but at

the same time alienated the remaing third. The

damage caused by initially starting out in 1898

was significant for a title which was already

dragging along in bi-monthly publication and thus

had a hard time attracting new readers to replace

those who dropped out. Things were

also hampered by Marvel's somewhat lukewarm

handling of the newly gained possibilities once

the Monster had gone from a Marvel character in

its "own world" to one which could

potentially interact with the Marvel Universe at

large. This option, however, was limited to

appearances in Giant-Size Werewolf by Night

#2 (October 1974) and The

Avengers #131-132 (January - February 1975),

and as both these storylines were quite detached

from the main title's ongoing plot they did

little to nothing to push Frankenstein

Monster in any way.

It is tempting to imagine,

for a second or two, a character such as Dr Doom

appearing in the Swiss Alps... but unfortunately,

editorial could not.

|

|

| |

| Nowhere did

the rift in the title's readership become more apparent

than in the letters pages, which had originally been

called Monster's Mailbox before being renamed Let's

be Frank! |

| |

| This new heading sounded

rather appropriate for the critcism which more

often than not raged in this readers' forum - it

almost seemed as though there was nothing short

of either loving the title or hating it. |

|

Click to read entire letters

page

|

|

| |

| The letters

page from Frankenstein Monster #17 depicts this

is an especially pronounced way as it contains very

little positive feedback in contrast to a wave of sharp

criticism. All of this, however, was in stark contrast to

the comments which would be published on the letters page

of Monster of Frankenstein #18, which would

overall lament the previous decline of the title but

praise the upward turn Moench had produced with issue

#16. But by that time, it was already too late. By mid-1975, Marvel

had lost $2 million and found itself in bad financial

shape. In response to this financial crisis, Marvel's

owner Cadence installed a new company president who

immediatley proceeded to cut down the number of titles

produced. As a result, Marvel's range of horror titles

almost collapsed: by the time the autumn production run

preparations were due, the fate of many Marvel horror

title was sealed, and the number of Marvel's horror

comics went down from 19 to 9. The first high-profile

victim - by name and popular culture status - of this

1975 horror genre cancellation wave was The

Frankenstein Monster. After 32 months and 18 issues,

it was the end of the road for the title in September

1975, and only one month later the Monster would be

followed by Man-Thing and the Mummy.

Sudden as the cancellation of the title appeared to be in

the end - taking place without announcement of any kind

and right in the midst of the storyline (usually, Marvel

tried to wrap up things in such cases) - it could not

have come as a surprise, given the fact that Moench was

transferred to other titles after issue #17 and the

plotting for what turned out to be the final issue handed

to Bill Mantlo - Marvel's "fill-in king" of the

late 1970s and an obvious case of a free writer with

nothing to lose on a title bound for limbo. In this case,

Mantlo's assignment lasted for one single issue before

the final curtain fell on The Frankenstein Monster.

|

| |

|

| |

| Having

filled Monster of Frankenstein #16 right up to

the brim with action and plot interest, Doug Moench

successfully continued his multi-layer approach in Frankenstein

Monster #17, and what this issue lacked in terms of

storytelling pace as compared to the previous issue it

more than made up with in terms of characterization and

plot development. Moench continued his mission to bring

the title back into line with its literary roots as the

whole underlying dilemma of the Frankenstein story once

again started to unfold - only that now it included the

Monster again, which through its regained ability to

speak returned to being the focal point of the story. |

| |

| On the metastory level of

character development, Moench instantly took

advantage of the Monster's return to speech and

the end of silence after 7 issues and 14 months

(which was even heralded in a blur on the cover

of Frankenstein Monster #17 - "Because

you demanded it -- the Monster speaks!"),

and depicted the Monster's thoughts as centering

quintessentially on the question of its identity,

and its opening lines on the splash page

immediately redefined the Monster. It

was no longer the lumbering, mindless heap of

flesh whose sole driving force is to wreak

bloodshed and revenge upon the descendants of its

creator, but rather an essentially human being

faced with complete uncertainty - and before it

can come to terms with anything, the Monster,

like all human beings, needs to know and

understand its roots - its true identity.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Moench

was now firmly in command of a plot which clearly

reflected on the story from a perspective very close to

Mary Shelley's. At the same time, Moench added new

elements from the modern setting which actually worked

and provided increased plot value and story interest. It

was a long way from some of those awkward twists and

turns which had plagued some earlier issues of Frankenstein

Monster, and it was done in the same swift but

determined way which Moench had displayed in transferring

the Monster to the present timeframe. Frankenstein

Monster #17 thus continued the action-driven

liveliness set by the previous issue (and which had been

sorely lacking throughout many issues of the series

before) in spite of also featuring some rather heavy

philosophical issues.

|

| |

|

|

But it worked, and not the

least because I.C.O.N. kept adding speed and zap

in the same tongue-in-cheek fun tradition which

make Nick Fury's S.H.I.E.L.D. or James Bond's

SPECTRE so effective as plot tools. Most

of all, I.C.O.N.'s android Berserker

(what a great codename to contrast with Indigo,

Cardinal and, above all, Rainbow)

provided a credible antagonist for the Monster -

and a persistent problem for the group of

supporting cast regulars trapped in the

Frankenstein residence which kept them busy and

added the necessary momentum to the overall

storyline.

|

|

| |

| However,

central to this issue is Moench's step of bringing back the

drama of the Frankenstein theme by asking the same

quintessential questions raised by Shelley's novel: is

Frankenstein just a misguided scientist who actually

means good, or is he a madman, a megalomaniac who sees

himself as God? And where, most importantly, does his

creation take its place in life - if at all? If it is not

a monster - does that make it a human being, or just

something else? |

| |

|

| |

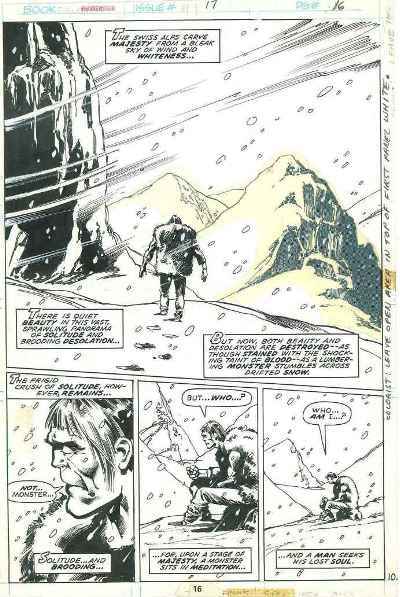

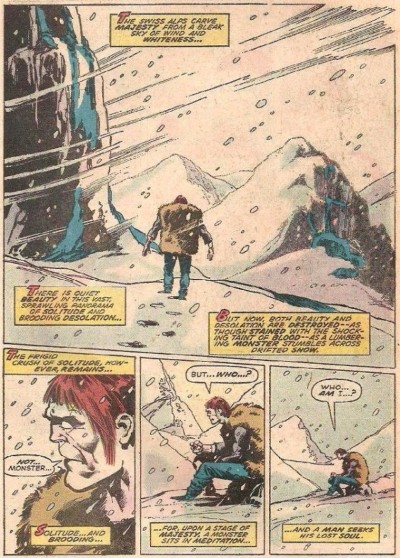

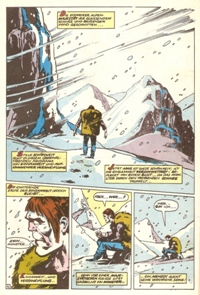

Left: Original art for The

Frankenstein Monster #17 (July 1975) pencilled

by Val Mayerik, inked by Bob McLeod and lettered by

Artie Simek (scanned from the original in my

personal collection).

Right: the same page as it appeared in print (colours

by Don Warfield). [click for larger

images]

|

| |

| It

is at this point that the series reached its best in

terms of the depth of original storytelling and plot

handling, and Mayerik's art throughout these pages is

amongst his best on the title as he depicts the white-out

of the Monster's thoughts and feelings in a similiar

surrounding. Doug Moench had been working with Val

Mayerik at

the time, and when he took over Frankenstein Monster

asked Mayerik if he would be interested in joining him on

that book. Mayerik's enthusiasm showed in his artwork,

and his style soon fused with Moench's writing to form a

distinctive rendition of the Frankenstein theme for

Marvel, including the Monster's appearance itself.

|

| |

(click to view larger image)

|

|

In Frankenstein

Monster #17, Mayerik's artwork renders both

Moench's dynamic and ponderous plot in fitting

visualisations. One example is the

page layout shown here, where staggered and

slanted panels form visual equations of the

perturbed context, and key elements of the

storytelling are drawn to protrude out of their

actual panel, such as the head of the Monster,

the flying feet of Caccone, or the word balloons

of the bottom panel - all adding speed and depth

to the artwork.

20th century popular culture

has established a strong relationship between the

human mind and the human brain in the context of

the Frankenstein theme, mostly ignoring the fact

that this topic is a century-old matter of

philosophical and scientific debate (Smart,

2007).

As a consequence, much of

what is commonly referred to as identity is

therefore associated with the brain - which in

turn raises the intriguing question also brought

up by Doug Moench in Frankenstein Monster #17:

whose brain was brought back to life by Victor

Frankenstein inside the Monster's skull?

|

|

| |

| The

question had been raised before in the letters pages of Frankenstein

Monster, but somewhat surprisingly Moench closed the

lid on this almost immediately after he opened the

subject by immediately having Veronica Frankenstein

inform Caccone, Prawn and the Monster that all of Victor

Frankenstein's notes have been lost over time. |

| |

| This handling of the

"brain question" was in sharp contrast

to previous pop culture interpretations of this

aspect of the Frankenstein saga (the seeds of

which were sown in the 1931 Karloff movie where the Monster

is given a defective brain due to the bungling of

Frankenstein’s assistant), but actually in

sync with the original novel, where Shelley

alludes to how Frankenstein got hold of some of

the body parts, but never mentions the brain

specifically. |

|

|

|

| |

"Who

shall conceive the horrors of my secret toil as I

dabbled among the unhallowed damps of the grave (...)

I collected bones from charnel-houses and disturbed,

with profane fingers, the tremendous secrets of the

human frame (...) The dissecting room and the

slaughter-house furnished many of my materials."

(Mary Shelley (1831), Frankenstein,

Chapter Four)

The

underlying reason for Universal's 1931 portrayal of the

bungling lab assistant’s accidental acquisition of a

defective brain was, of course, to present this as the

cause of the monster’s malevolence and socially

disturbing behaviour. However, this completely reverses

the central theme of the book, where Frankenstein's

creature starts out in life with the full potential for

good but is essentially twisted into evil by an unjust

and unwelcoming society. Shelley made it clear that she

felt that the social milieu has an important

impact on character, and her novel strongly suggests that

criminality and violence are to be understood as the

result of unhealthy societies - not defective brains or,

to update the concept, "bad genes".

The source

of the monster’s perceived evil nature is indeed one

of the central themes of the Frankenstein novel, but the

adaptations of Shelley's work in popular culture

effectively did away with this. It is therefore all the

more astonishing that a comic adaptation working with

original plot material would actually turn its focus to

exactly these questions - but that's just what Doug

Moench did in Frankenstein Monster #17.

|

| |

Berserker

redux as a typo sneaks into a cover blurb

|

|

In adressing the brain

question with the answer that all records of

Victor Frankenstein have been lost, Moench

provides the readers of the comic book with

basically the same amount of information - namely

none - given by Shelly to the reader of the

novel. It is admittedly a subtle way of telling

the readers that this question really is of

secondary (if any) importance, but it is followed

up by a Monster whose words and thoughts display

a sensitivity and depth not associated with a

"man-brute" - as one of the blurbs on

the cover screams out virtually in contradiction

to the contents of the issue. |

|

| |

| However,

the amount of thought and consideration invested by

Moench into bringing the Monster closer to its literary

essentials was not to be rewarded. The creative team had

managed to counteract the downward spiral the title had

found itself in for so long, but it was not enough to

save the book in a time when Marvel itself was in a deep

crisis. |

| |

| And so, Moench

wrapped up his writing, and fittingly

enough the last panel on the last page of

Frankenstein Monster #17 carries

the caption "FIN",

even though this issue would only be the

penultimate and not the final one. But

the book did end there for Moench, who

brought his plot and storyline to a point

which culminated in a last scene which

equalled many Hollywood closing takes in

the tradition of Casablanca when

the Monster and the Berserker walk away

from the reader and off into the

distance, "a man who is no

longer a monster... and a machine who is

no longer mindless". With

this final take on the Monster, Frankenstein

Monster #17 almost also becomes the de

facto ending for the title itself as

Moench's replacement Bill Mantlo

immediately steered away from any

closeness to Shelley and virtually wrote

issue #18 as though it came from a

different series.

|

|

|

|

|