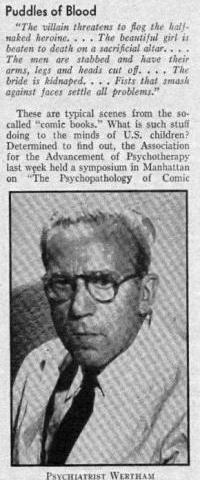

| Now known under the anglicised

name Fredric Wertham he received US citizenship in

1927 and moved to New York City in 1932 to work as

the senior psychiatrist for the city's Department of

Hospitals. As part of his primary job duties Wertham

was called upon to provide psychiatric examinations

in conjunction with criminal court cases, and in this

function he became involved in the 1935 trial of

serial killer Hamilton Howard "Albert"

Fish, also known as the Gray Man, Werewolf of

Wysteria, the Brooklyn Vampire, and The Boogeyman. Wertham's defense examination concluded that Fish was the most deranged human being he had ever met, but the court judged the accused to be legally sane and sent him to the the electric chair. Even years later, Wertham would heavily criticise the prosecution's psychiatric witnesses for - in his point of view - sensational statements and lack of interest in the underlying factors which triggered Fish's terrible crimes, and in 1949 he described the case and his involvement in other murder trials in his book The Show of Violence. |

|

| Working

at the Bellevue Hospital Center and its well known

psychiatric facilities since 1932 and appointed

director of the Bellevue Mental Hygiene Clinic in

1936, Wertham came into increasing contact with

troubled youth, alongside which he developed a

clinical interest in popular culture. His focus began to zoom in on what he perceived to be the negative influences of mass media, and after his appointment as director of the psychiatric services at the Queen's Hospital Center in 1940, Wertham wrote and published Dark Legend in 1941. Based on the true life story of a 17-year-old murderer, Wertham depicted the youth as having a dark fantasy life which triggered his crime and was based on movies, radio plays and - comic books. |

|

| GROWING PUBLIC CONCERN OVER COMIC BOOKS | |

With

the comic book industry expanding quickly, comics had

started to attract the attention of educators as of

the mid-1930s and a number of essays and articles

were published on the subject which displayed a

growing tendency to view comic books as a

detrimental influence on children:

The vocabulary of the comic book critics became increasingly pronounced, and in 1940 the National Education Association Journal published an article discussing "an antidote to the comic magazine poison" (Decker, 1987), whereas amicable portrayals of comic books and their creators such as Sheridan (1942) soon became scarce exceptions. Public comic book bashing - conducted in a tone of increasingly martial rage - was therefore far from being something new when Fredric Wertham joined the clamouring. He had since continued his psychiatric work and in 1946 drummed up private support and funding to establish the Lafargue Mental Hygiene Clinic in Harlem, offering counseling to poor people regardless of race (although most patients came from the African American community) or ability to pay. Driven by Wertham's belief in the application of psychiatry to the masses, the clinic also rejected abstract notions of psychoanalytic neurosis and worked on the concept basis that an individual's social environment was largely responsible for his or her actions, regardless of whether they were noble or anti-social (Eversley, 2001). |

|

|

|

| Through his work as a forensic psychiatrist, Wertham reached the conclusion that violence was not a deviation from mainstream society but an integral part of that mainstream, because in his eyes the various settings of society influenced and even triggered such violence. | |

For Wertham, juvenile delinquents

were thus not born to be felons - on the contrary,

they were acting out a social misery which was an

everyday part of their life, and he thus found it

inacceptable to place the entire blame on these

children or their parents for any anti-social acts

they committed.

This was a sharp and pronounced deviation from the majority views of the times, which is summed up by a newspaper report on the opening of the Lafargue Clinic in 1946 which read "They're crazy anyway" (Eversley, 2001) and pointed to the common belief that ethnic minorities and the socially underprivileged had "inherent problems". Indeed, Wertham's approach still incurs criticism today because it seemingly turns perpetrators into victims almost automatically and under all circumstances. Defending this point of view was thus all the more difficult for Wertham in the 1940s, not the least because it substituted a simple answer ("bad genes") with a highly complex alternative ("socio-economic influences"). It is very unlikely that Wertham was not aware of the fact that the reality of any society would provide for a plethora of possible triggers for juvenile violence, not to mention post-WW2 Harlem with its racial discrimination background and reduced access to climbing up the social ladder. At this point, however, the psychiatrist Wertham gradually turned into the social reformer Wertham, and findings founded on facts turned into belief and finally conviction. |

It was here that Wertham's focus on comic books as a primary trigger for anti-social behaviour began. |

Along

with this fundamental change in defining his own

role, Wertham dropped his professional objectivity

and took on a personal agenda.

Throwing virtually everything to the wind, Wertham gradually gave in to the temptation of putting forward a simple explanation in order to bolster his views on the underlying causes of juvenile delinquency, and during his sessions with youngsters from the neighbourhood of the Lafargue Clinic (named after the creole doctor Paul Lafargue who was also the son-in-law of Karl Marx) Wertham noticed that comic books were mentioned here and there, and steadily began to develop his idea that comic books were such a major "tool of seduction" that they had to be seen as a primary cause to blame for juvenile delinquency. |

|

|

|

After two years at Lafargue,

however, Fredric Wertham's approach to his

work relating to comic books had lost all

methodological soundness. He focussed exclusively on

a very specific group of individuals - troubled

youngsters who were taken to the Lafargue Clinic for

psychiatric counseling - without ever setting up or

studying a proper control group of contrasting

individuals. Wertham simply excused himself from such

basic scientific research procedures by implying that

the thoroughness of his work was beyond question, let

alone doubt.

In reality, Wertham's clinical work was constantly concerned with the underprivileged youth of a very particular part of New York City. It should thus not have been surprising that individuals who read comic books (which were not only amongst the most widespread popular entertainment at the time but also amongst the cheapest) would be found in abundance in this specific socio-economic environment, including the higher percentage of individuals with a delinquency problem which one would expect to see in such a neighbourhood. Wertham not only ignored the fact that a large percentage of all kids at the time were reading comic books - the majority of whose behaviour was completely inconspicuous and who never showed up at Lafargue or indeed any other institution. He also blacked out contemporary research results which indicated - albeit reluctantly - that there was no negative influence discernable with regard to the intelligence of comic book readers versus those children who did not read comics (Witty, 1941). |

|

| 1948 - "THE PSYCHOPATHOLOGY OF COMIC BOOKS": LAUNCHING THE ANTI-COMICS MOVEMENT | |

| To all

intents and purposes, Wertham's work had gone beyond

the point of no return in terms of scientifically

sound research on which to base any valid statements.

His initial cause was still a noble one - defending

the underpriviledged child and sparing him a happless

life, possibly in correctional institutions - but his

modus operandi now became increasingly

radical as he proceeded under the smokescreen of his

professional standing - insisting that his views

originated from "clinical judgment"

- in what now started to turn into an all-out

campaign. Wertham was also becoming increasingly

critical of American commercial culture as a whole,

which in his view subverted the morailty of children

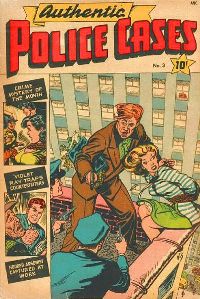

simply for the sake of profit (Wright, 2001). In 1948 Wertham began to take a more active stance and initiated a symposium on The Psychopathology of Comic Books which was held on 19 March in New York City by the Association for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. It was here that he took center stage for the first time, chairing the event and declaring it to be a milestone by gathering several speakers who were presented as specialists on the topic of comic books.

This appraisal of the event is highly questionable. Straight out of the starting box, Wertham alluded to previous tampering and hence foul play by the industry, for which he provided no further detail (let alone proof). In effect, his statement was nothing but a first strategic move to damage the reputability of the comic book publishing trade right from the start. As for the scientific character of the meeting, it can be noted that the symposium was above all characterized by sweeping statements of condemnation made by virtually all of the participants. Some were fairly subtle, but others hardly disguised their evidently unscientific attitude and approach, such as "Manhattan Folklorist" (as Time Magazine dubbed him) Gerson Legman who deplored the violence in all comic books, hitting out at "the disguises" used by Disney, and finally concluding that comic books virtually reeked of "anti-intellectuality" and even "naziism". All contributions, as well as a brief recapitulation of the discussions held, were collected in the American Journal of Psychotherapy, vol 2 #3, in July 1948. Fredric Wertham had left the confines of his Lafargue Clinic and launched the anti-comic book movement. Although de facto self-declared, he was the ideal leader for this movement. As a children's psychiatrist, he could present himself as an impartial professional whose standing was not to be doubted. |

|

| It really wasn't such a big deal for Wertham, in spite of the fact that Time Magazine brought nationwide circulation. In contrast, the weekly Collier's could offer far less readers (around 2,5 million copies) but an article the periodical ran two days prior to Time Magazine's report on the symposium would add speed and public attention to Wertham's cause virtually over night. |

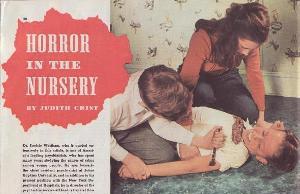

| "HORROR IN THE NURSERY" - THE SHAPING OF WERTHAM'S MANIFESTO |

| Penned by Judith Crist with the sensational title "Horror in the Nursery", the article in the March 27th 1948 issue of Collier's - illustrated with specially staged photographs - was in essence little more than an extended platform for Wertham's rallying call against comic books which he had launched at the symposium (which Crist had already reported on in the New York Herald Tribune of 21 March 1948 under the headline "Comic Books Dissected at Psychiatric Forum"). |

|

The article starts out with a

claim to the validity of its content by asserting

Wertham's professional validity.

As the article proves, Fredric Wertham was certainly on his way to become a publicly noted psychiatrist. Presenting him to the readers as a leading member of his profession, however, was based primarily - if not entirely - on a purely personal point of view. |

The

psychiatrist's fight against comic books must have

struck a chord with Crist - so much so that she would

be present at the 1954 Senate hearings.

By that time, however, Crist was a veteran follower of Wertham's cause, having already pledged her allegiance to the psychiatrist's drive against comic books in a letter in 1948.

It is therefore hardly surprising that "Horror in the Nursery" concentrates entirely on Wertham's take on the subject and embraces his views as factual information from an expert who is not to be doubted. As a result, the article can be seen as both a programmatic manifesto and a strategic outline of Wertham's upcoming crusade against the comic book industry. |

| WERTHAM'S FOUR POINT STRATEGY |

| "Horror

in the Nursery" almost serves as textbook to

illustrate the strategy which Wertham would pursue in

the following years in his move against comic books

and the comic book industry. He cleverly combined his

professional standing and reputation with simple but

coherent tactical elements which would allow him to

seize public platforms, claim moral superiority,

discredit the object of his criticism and anyone

defending it, and then deal out the punches before

the "other side", i.e. the comic book

industry, had even entered the ring. It was something

of a populist "Blitzkrieg"

strategy, and in most cases it worked out brilliantly

for Wertham. Step 1 - Point out the relevance of the issue "comic books" It was extremely important for Wertham to assure himself of an audience if he wanted to achieve anything, so the first thing to do was to ascertain the importance and timeliness of his topic. He did this by pointing out just how popular comic books were and by giving an estimate of around 60 million copies which he believed to be in circulation each and every month. Step 2 - Deplore the negative characteristics and effects of comic books Wertham's next step was to move on from such impressive figures - clearly this was a nationwide mass phenomenon - and deplore the negative influence and effect of comic books.

It is clear from these few sentences that Wertham was now targeting the industry in an increasingly aggressive way by not only attributing all but the most negative qualities to their publications in general but also by accusing the industry of deliberately corrupting moral and ethic standards. Step 3 - Claim a commonly accepted superior moral motivation Wertham's next step was to in effect preventively excuse himself with regard to any statements which some might deem to be inappropriate or exaggerated by claiming a moral as much as a professional motivation for his actions.

Step 4 - Discredit the critics Having established the noble cause of his mission, Wertham was now only left with the task of how to deal with opposing views and critics. In true populist fashion, he effectively avoided entering into any substantial discussions by simply discrediting the source of any criticism voiced towards his position. He had already done so with the comic book industry at the symposium, but in "Horror in the Nursery" he pointed his finger to anyone who already did or would dare to have an opinion not in line with his own - especially colleagues from his own profession.

|

The

stark modus operandi laid out in

"Horror in the Nursery" would prove highly

effective for Wertham, and although he would also

provide more temperate remarks, these would - in

Priest's article just as in upcoming publications -

almost instantly be covered up again by absolute

statements.

The solution for the problem according to Wertham was to stop circulation of the most offensive books through local enforcement of existing penal codes by district attorneys or license commissioners. |

|

|

|

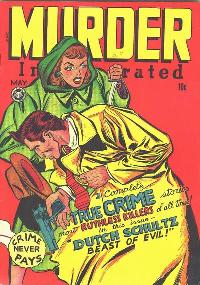

| WERTHAM KINDLES THE FIRE: THE COMICS - VERY FUNNY | |

| Comic

books were now a topic of discussion and interest to

a growing portion of the public, and Wertham's

arguments quickly gained momentum as more periodicals

turned to him as the expert on the matter. Next in line was the Saturday Review of Literature, which ran an article by Wertham titled "The Comics - very funny" in its issue of 29 May 1948. It became one of the most widely read and discussed articles ever to appear in the Saturday Review of Literature (Haverstick, 1957) and would be included almost ten years after its original publication in the compendium The Saturday Review of Literature Treasury. Now acting as author and not as interviewee, Wertham took an even more active stance and listed a number of counterarguments to his own views which he then refuted, mostly by ridiculing them. He thus continued to use a pronouncedly populistic style but now added outright aggressive vocabulary as he dismissed any colleagues from his profession who functioned as experts for certain publishers of comics as "apologists [who] function under the auspices of the comic-book business" (Wertham, 1948b). The industry itself was dismissed with the use of the comparison already heard at the symposium.

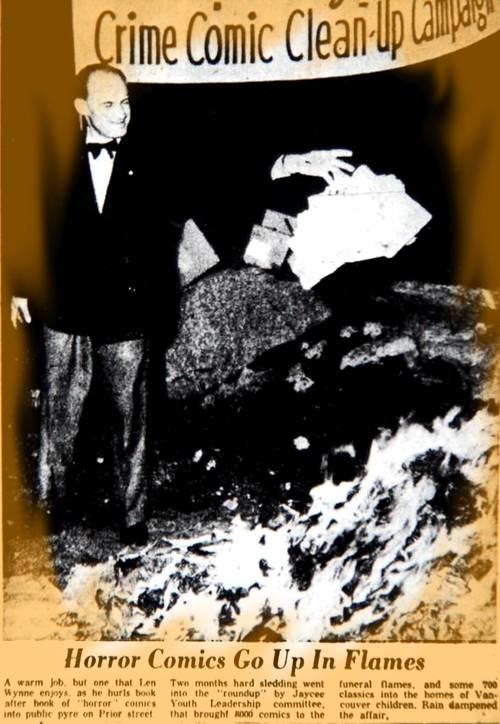

All of this, however, paled in comparison to another statement by Wertham in which he - literally - kindled the fire of the anti-comics movement.

The statement rests there, with no further comment, and there is nothing in Wertham's article to indicate that he did not, explicitly or implicitly, endorse the burning of comic books. For a German born psychiatrist to write so casually about this, and to do so only three years after the fall of the Nazi terror regime in his country of origin, is striking. Fredric Wertham was not, of course, a Nazi. But Fredric Wertham was an intelligent man who increasingly chose to ignore his own best knowledge, which surely included the famous quote from his fellow countryman Heinrich Heine.

|

|

The same article in the Schenectady Gazette also clearly illustrated which kind of pressure groups Wertham's drive was triggering.

Although Wertham himself leaned to the political left (Wright, 2001), he was now attracting wide support from right-wing conservative and moralist movements which openly embraced or even demanded censorship (such as the National Legion of Decency). Fittingly, the brief report in Time Magazine on the burning in Binghamton was featured in the "Morals & Manners: Americana" section and was immediately followed by a report from Macon, Georgia, where "the Ku Klux Klan initiated 300 new members in a public ceremony in the City Auditorium. Among the participants were 150 masked women. One Klansman, apparently believing that the education of prospective members can't be started too early, brought along his young daughter - in full regalia, except for mask". The writing on the wall could not have been more obvious. |

| Other

burnings also came to the public's attention. Whereas

children - overseen by priests, teachers and parents

- publicly burned several hundred comic books in

Spencer, West Virgina (Hajdu, 2008), boy scouts in

New Jersey gathered comics and burned them in the

hopes of earning their Eagle Scout rank (Gabriel,

2001). Wertham could not be pinned down as the direct driving force behind these and many similar events - he never propagated such measures. However, such events would not have taken place without the feverish mental framework established by Wertham in his writings and presentations on comic books as a general threat. Typically, he was not the man to set fire to the explosives - he only handed out the matches. Fredric Wertham thus increasingly became a man willing to sacrifice some of the fundamental ideals of a democratic state of law if it served his cause. As the anti-comics movement quickly came to the realization that preventing the sales of objectionable comics at a legislative level - as Wertham had suggested himself - would prove difficult if not entirely impossible in the face of the First Amendment, and that the only way to get at the comic book industry was through concerted and continued pressure from the public and increasing retail bans throughout the country, Wertham was willing and ready to provide the populist campaign needed to create and sustain precisely such pressure. |

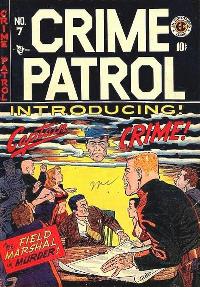

| THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY'S REACTION - THE 1948 FOUNDING OF THE ACMP |

| Criticism

towards their publications was nothing new to the

comic book industry, but so far it had always been

possible to either just more or less ignore it or

counteract any negative publicity with the engagement

of educators who would act as an in-house review

committee. However, it quickly became apparent that

Wertham and his campaign were working on a completely

different scale and with a force never seen before.

To make things worse, the industry also lacked

someone of a similar standing and stamina whom they

could have sent out into the arena to challenge

Wertham. And worst of all, a certain percentage of

their comic books actually were just as lurid and

brainless as Wertham described them to be. On top of

all this, civic and religious groups throughout

America now actively pressured distributors and

retailers to remove objectionable comics from their

newsstands. The industry urgently needed to appease

their challengers to a certain degree, and it found a

partial and quick solution in copying the Hollywood

movie industry's 1930s move to enact a

self-regulating body to oversee a code of standards

that all films would adhere to. As a result, the Association of Comics Magazines Publishers (ACMP) was formed on 1 July 1948 to regulate the content of comic books. The founding members included publishers Leverett Gleason of Lev Gleason Publications, Bill Gaines of EC Comics, Harolod Moore of Famous Funnies, and Rae Herman of Orbit Publications, with attorney Henry E. Schultz serving as executive director. The ACMP quickly released their "Publishers Code", drawing heavily on the Hollywood "Production Code" (better known as the "Hays Code") which had been drafted in similar circumstances, i.e. to stave off external regulation. |

| Likewise, the Production Code

forbid portrayals of crime that might "throw

sympathy against the law" or "weaken

respect for established authority". It also

outlawed "ridicule or attack on

any religious or racial group" and "sexy,

wanton comics" were banned from publication. "Regulated" comic books were intended to display a seal of approval in the form of a star. The code, however, was an emergency move hastily set up, and was quickly ignored by both large and small publishers, whilst some publishers (e.g. Dell Comics) even refused to join the organization, leading others - including the founding member EC Comics - to quit and end their participation in the scheme. The ACMP seal of approval was further weakened by the fact that it was used without any formal process of review, and by 1950 the ACMP was reduced to a skeleton. During the 1954 Senate Subcommittee hearings, Schultz gave his opersonal opinion on why the ACMP faltered. |

|

|

| READER'S DIGEST - A BLUEPRINT FOR ANTI COMIC BOOK ACTIVISTS |

In August 1948,

Wertham's article "The comics - very funny"

from the Saturday Review of Literature was

published in a condensed version but under the same

title in Reader's Digest. As the

psychiatrist from Harlem and his crusade became

darlings of the conservative mainstream media, the

widening public platform Wertham achieved through

this resulted not only in a growing level of support

but also in numerous local and regional initiatives.

Wertham was increasingly becoming the spiritus

rector who provided the ideology for others to

follow and enact, and many statements from the August

1948 issue of Reader's Digest served

precisely that purpose.

In a short editorial text accompanying Wertham's article, readers were also told that

In addition, Reader's Digest added an update on measures taken against comic books.

|

The panel even took

into account the newly founded ACMP and was eager not

to generalize.

Differentiation, however, was not inspired by Fredric Wertham's line of movement - on the contrary: it was a reaction by those who felt that Wertham had touched upon something which merited some inspection without instantly reducing - figuratively or literally - the object to ashes. |

| 1949 - WERTHAM'S CRITICS FIND THEIR VOICE |

| Events

such as the "symposium" in Milwaukee were

indicative of the subtle changes which were taking

place regarding the discussion of comic books.

Throughout much of 1948, Wertham had succeeded in

occupying the playing field virtually by himself and

therefore scoring point after point. The comic book

industry was too stunned and probably also too sure

of itself to react immediately, and those who would

engage in a serious discussion of the issues raised

by Wertham took some time to properly review the

situation before stating their position. For that

period of time, Wertham's increasingly populistic

agenda and style had effectively monopolized the

issue of how comic books related to juvenile

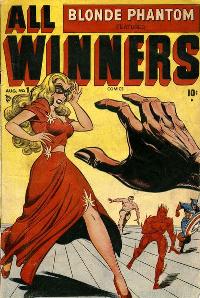

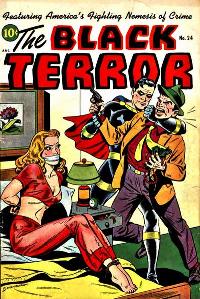

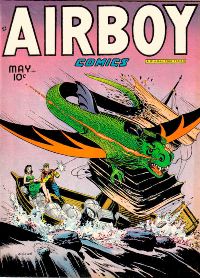

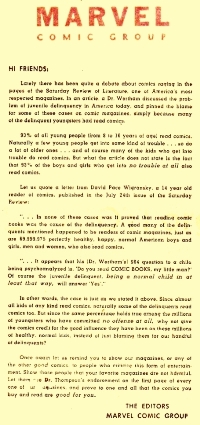

delinquency and anti-social behaviour. By the beginning of the following year, however, Wertham's critics began to speak up more frequently and more prominently, and comic book publishers started to directly address the accusations made. Timely - using the label and logo "Marvel Comics" for several months in 1949 and 1950 - grabbed the bull right by the horns in full-page editorials. |

| Clearly

this was not an impartial statement either, much as

Wertham himself had lost almost all qualities of a

balanced point of view. Nevertheless, Timely's

editorial did point to the weakest point of Wertham's

argument, and this was also increasingly noted by

those who had no personal share in this conflict. In January 1949, columnist Norbert Muhlen - German born like Wertham - reviewed the issues raised by Wertham in an article titled "Comic Books and Other Horrors - Prep School for Totalitarian Society?" in the periodical Commentary. Muhlen himself felt rather strongly about what he perceived to be a substantial increase of violence in mass culture, including comic books, and that "mass entertainment by violence tends to become the child's education to violence" (Muhlen, 1949b). But in spite of his proximity to Wertham regarding his very sceptical view of popular and mass culture, Muhlen voiced substantial objections to Wertham's approach as he felt that the discussion on comic books had turned into something of a "civil war among psychiatrists" (Muhlen, 1949a) and that Wertham had become a monocausationist in the process. Muhlen also argued that Wertham had made an important mistake: comic books did not cause juvenile delinquency, but many of the themes and stories featured in comic books came from the same common root. Muhlen himself critized comic books for favouring, in his view, an authoritarian rather than a democratic society but at the same questioned Wertham's approach in that respect, together with the lack of sound data and methodology.

Muhlen thus introduced a significant change of tone into the discussion. Whereas Wertham had increasingly strayed from what could be considered an opinion based on scientifically sound methodology and facts and had first leaned towards and finally embraced an outright populistic and at times demagogic approach over the course of the year 1948, Muhlen demonstrated that Wertham's position was so overgeneralized as to ultimately reduce it to nothing more than an absolute personal opinion - in spite of sharing Wertham's critical view towards the function and effects of comic books for society. In other words, Muhlen tried to advocate a more balanced discussion of the topic in question. Wertham's reaction was to reproach Muhlen for having misquoted him - and accusing Muhlen of having done so deliberately. Muhlen's challenge regarding the lack of access to Wertham's case material, however, remained unanswered (Wertham, 1949). Fredric Wertham, it seemed, was not interested in a real discussion. An important representative from the comic book industry, however, was: Whitney Ellsworth, Editorial Director of National Comics Publications, Inc. - better known as DC - engaged in an exchange of views and comments with Muhlen through the letters page of the March 1949 issue of Commentary. The first issue taken up by Ellsworth was Muhlen's view that there was a fundamental difference between the “older, much-censored, and more refined newspaper comic strips” (Muhlen, 1949a) and the “dehumanized, concentrated, and repetitious showing of death and destruction” (Muhlen, 1949a) in comic books. Ellsworth disagreed on this and pointed out that Dick Tracy and a number of other newspaper crime strips were every bit as brutal and gory as anything that might be found in even the most violent comic book (Ellsworth favoured the term "comics magazine"). Muhlen, however, insisted that there was a fundamental difference and that "scenes of cruelty characterize a minority of the newspaper strips, while they form the great mass of comic book content" (Muhlen, 1949c). The fact that comics were published in different forms (i.e. strips and magazines) had never been of concern to Wertham, and the fact that Muhlen and Ellsworth discussed this aspect is indicative of the fact that they were actually engaged in a real discussion, probing many aspects of the topic and not restricting themselves to premature judgements. The focus of the public discussion as influenced by Wertham, however, was clearly on comic books and not comic strips. Far more closer to the core of Wertham's discussion - and indeed the focal point - was the question of to what extent comic books gave readers ideas and prototypical step-by-step illustrations to follow. In his article, Muhlen had related what is possibly the classic story of "comic book reenactment" - and most certainly an urban legend. |

Ellsworth's

arguments were strong, and they revealed an aspect of

the anti-comics movement which had so far been

systematically left aside: in essence, Fredric

Wertham had been allowed to make just about any

statement without ever having to supply any factual

evidence. DC's editorial director also pointed out

just how restricted and incomplete the analysis based

on a comics-only focus could be.

Ellsworth also commented on the question of self-regulation by the comic book industry to some length and detail in order to set the record straight from his side.

The DC Editorial Advisory Board at the time consisted of psychiatrists and educators, namely Dr Lauretta Bender (Associate Professor of Psychiatry, School of Medicine, New York University), Josette Frank (Consultant on Children's Reading, Child Study Association of America), Dr C. Bowie Millican (Department of English Literature, New York University), Dr W. W. D. Sones (Professor of Education and Director of Curriculum Study, University of Pittsburgh) and Dr S. Harcourt Peppard (formerly Acting Director of the Bureau of Child Guidance, Board of Education, City of New York, and then Director of the Essex County (New Jersey) Juvenile Clinic). This grouping of professionals was most obviously on a par with Dr Fredric Wertham to say the least, and Whitney Ellsworth concluded his contribution by returning to the point in question which had triggered the whole discussion on comic books launched by Wertham: the possible causality between comic books and juvenile delinquency. In his closing remarks, Ellsworth turned to what Kenneth Warburton, Director of the Youth Counsel Bureau of the Bronx District Attorney's office, had to offer on the subject.

This argument was, of course, directed at Wertham and not Muhlen, as Ellsworth and Muhlen found agreement on that point.

It is interesting to note that - with Wertham absent - Muhlen and Ellsworth were able to engage in a discussion which, although conducted with stiff arguments from both sides, included listening to what the other party had to say. In the end, this resulted in some common positions and views covered by both, as well as an agreement to disagree on other aspects. Ultimately, the letters pages of Commentary in early 1949 proved that a civilised exchange of views on the topic of comic books and their - possibly negative - effects on society and youngsters was indeed possible. However, Commentary was only into its forth year of publication and its circulation was negligible in comparison to Reader's Digest. Ellsworth and Muhlen were thus heard only by a few. Nevertheless, Wertham's critics began to gather momentum. |

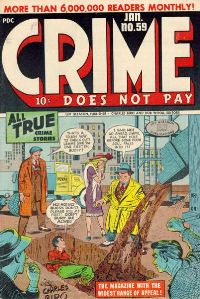

| THE TURNING OF THE TIDE |

| Fredric

Wertham had experienced an initial wave of media and

public support in early to mid-1948, but now the tide

was slowly beginning to turn. Media coverage for

Wertham himself was markedly down and his

continuously overgeneralized bashing of the comic

book industry was no longer met with stunned silence.

Following accusations regarding excessive violence

which Wertham made in an article in the March 1949

issue of National Parent Teacher Magazine entitled

"What Are Comic Books ? A Study Course for

Parents", Fawcett Publications threatened the

periodical with a libel suit. Wertham, however, stood

his ground, was backed by the editors of National

Parent Teacher Magazine, and in the end nothing

happened. On another legal front, however, the anti-comics movement was faced with defeat as various courtrooms throughout the US would declare anti-comics legislation (drawn up in several states as a reaction to the public outcry) to be in violation of the first amendment and thus unconstitutional. The basis for these court cases had been laid only ten days after Wertham's initial NYC symposium as the Supreme Court delivered its ruling in the case of Winters v. People of the State of New York (333 U.S. 507, 1948) on 29 March 1948. The Supreme Court overturned a New York state law prohibiting the publication or distribution of "true crime" books and magazines. One of the important reasons for the court's decision was based on the finding that the law was too vague and broad, thus failing to create a context in which a well-intentioned distributor could know when he might be held to have ignored such a prohibition. This resulted in a situation where the protection of free speech was at stake.

Wertham's crusade had thus been hampered by legal constraints straight out of the starting box, and although his followers would at times try to claim that "trash" such as comic books did not constitute protected speech, the reverberations of the Supreme Court ruling would be all too evident and damaging for Wertham's agenda. Municipal legislation such as the ban of 36 titles in Detroit - being one of fiftiy cities to impose anti-comics measures (Wright, 2001) - or Los Angeles County's outright ban of the sale of any crime comic to a minor (with a penalty including up to 6 months in jail) now started to fall one after the other on the common grounds of being unconstitutional, and subsequently politicians - some of which had embraced Wertham's topic with open arms - started to shy away (Wright, 2001). The anti-comics movement was denied the legal backing it sought in the US, but not elsewhere, as both Canada and France passed national anti-comics laws in 1949 (Introvigne, 2003). In the US, however, public discussion gradually acknowledged previous, more positive evaluations of comic books by renowned individuals, such as Dr Benjamin Spock, one of the most influential child-care experts, who had commented favourably on comic books in his The Common Sense Book of Baby and Child Care in 1946. Spock even felt that violence in comics could serve a healthy emotional purpose for youngsters because it served as a means of indulging in aggressiveness without the need of acting it out (Wright, 2001). Wertham was no longer omnipresent in the media and his major publication effort for 1949 was his book Show of Violence, in which he described his experience as a forensic psychiatrist. Nevertheless, he was now also feeling the turning of the tide on a very personal level, as more and more respected members from the scientific community identified him as the leader of the pack and started to dissect his meagre data and his doubtful methodology in various media and scholarly publications. In February 1949, Dr Paul Tappan, a professor of sociology at New York University, dismissed Wertham's ideas as over-simplification in the New York Times (Wright, 2001). |

|

The year turned out to be a lean

one for Fredric Wertham's anti-comics crusade in

comparison to 1948, and it ended with an outright

bashing when the Journal of Educational Sociology

devoted its entire December 1949 issue to the topic

of comic books - and directed nothing but criticism

towards Wertham. The editorial warned of impending censorship, and the contributors all agreed that the problem of juvenile dleinquency could not be solved by simply finding and brandishing a scapegoat, which in this case was the comic book industry and its publications. |

From

the industry's point of view, ACMP chairman Henry E.

Schultz - not surprisingly - found no kind words for

Wertham.

Being essentially a partisan opinion, Schultz's contribution could easily be shrugged off by Wertham and his followers, but the views expressed by other authors proved extremely damaging. An outright desaster for the anti-comics movement and Wertham's personal standing was the contribution by Frederic M. Thrasher, professor of educational sociology at New York University. Not only was Thrasher a renowned expert on juvenile delinquency who had conducted extensive research into the gangs of Chicago but he was also the initiator of media studies at NYU and conducted a series of studies on the effects of motion pictures on children. On top of all this, he also served widely as a consultant to groups concerned with movies, crime, prison reform and the prevention of juvenile delinquency.

In essence, Thrasher meticulously dragged all of Wertham's methodological and analytical weaknesses out into the open for everybody to see, and it contrasted sharply with Thrasher's sound scholarly presentation and the ramifications of his views through the quoting of work by other experts in the field. At least in the pages of the Journal of Educational Sociology, Wertham was completely discredited. It was a beating, but Wertham could still console himself through the fact that this took place in front of a rather restricted audience and not, for example, in the pages of Reader's Digest. |

| SUMMARY - WERTHAM AND THE 1940s ANTI-COMICS MOVEMENT |

| The

drive to censor comic books or bully them off the

market in the US had a long standing by the time

Wertham joined the cause in 1948, but it had been an

uncoordinated series of individual statements and

events which failed to make more than a short and at

best regional impact. When Wertham stepped out of the

Harlem Lafargue Clinic and onto the scene of a

Manhattan symposium, he instantly gave the existing

anti-comics movement what it needed most: a strong

leading hand and a powerful aura of professional

respect and moral integrity. He was, quite simply,

the ideal individual to become the personified

anti-comics icon - because unlike other individuals

he combined all the required qualities for success in

his own personality. His political standing (which was far more leftist than the many portraits which describe him as a liberal make it appear to be) did not contradict an elitist notion (in this case regarding culture) which in turn gave rise to a personal view of holding a position of absolute insight and truth. These qualities effectively made him a highly talented populist, as Wertham also had an appetite for attention and understood how to use the media. But it would never have worked out they way it did if it hadn't been for Wertham's professional standing, which gave him a mainstream credibility and a broad acceptance by the media and audiences alike - or, in the words of Stan Lee, his antipode in terms of comic book history iconicity:

Another important element for the anti-comic book movement was that Wertham was in a position to claim not just professional but practical experience through his work at the Lafargue Clinic. |

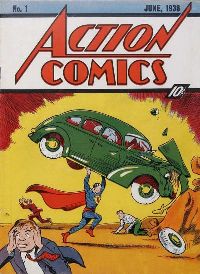

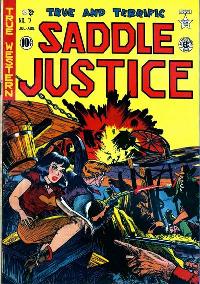

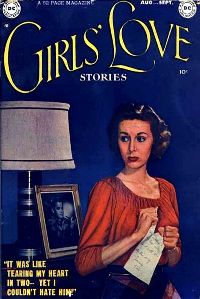

| Refering constantly to his

"clincial research" in said institution,

Wertham could instantly add the enormous weight of

"practical experience" to his line of

arguments. On a factual level, Wertham was probably aware of the blatant weaknesses of his studies at Lafargue as a basis for what he claimed to be able to draw from them - why else would he have chosen not to respond to his critics such as Muhlen and Thrasher? If his data and methodology from Lafargue was as sound and as elucidating as he claimed, he would certainly have published it, and with the utmost joy. His complete silence in that respect speaks volumes in comparison to his verbosity throughout 1948 and 1949, and substantiates the criticism in that respect with which he was confronted. In fact, this tell-tale shroud of silence continued even after Fredric Wertham's death, when his collected papers were presented to the Library of Congress by the estate of his wife, Florence Hesketh Wertham, in 1987. Acces to these papers and documents was to be restricted until 20 May 2002, with the exception of individuals receiving permission of the personal representatives of the Wertham estate. At the request of the Wertham family, this date was extended twice up until 20 May 2010 (governmentattic.org, 2009). As of that date, most of the papers are now accessible by appointment. As the decade of the 1940s came to an end, Wertham's activism in the anti-comics movement cooled off for a while before he would re-emerge in the early 1950s. The anti-comics movement itself would march on, but the temporary absence of its major leading figure was felt. Wertham possibly withdrew for the time being due to the growing criticism he personally encountered, but another major factor can certainly be found in the change taking place in the comic book industry's output itself. Crime comics remained popular, but the superhero comics increasingly lost favour amongst readers and in 1949 Timely's signature title Marvel Mystery Comics was cancelled, leaving the Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch without a home. Western comics became more and more popular, a genre which would seem a lot harder to criticize in a way which would appeal to the mostly conservative anti-comics movement, and the newly emerging romance comics were completely free of any violence or sexuality and thus automatically took some companies out of Wertham's line of fire. In the case of Timely, two thirds of its titles were directed at a female readership by the end of the decade (Robbins 1999). |

| No analysis of Wertham's role in the American anti-comic book movement can, of course, be complete without fully considering his main era of acitivity and impact, the 1950s. However, too many scholars and comic book enthusiasts seem to focus exclusively on The Seduction of the Innocent and the events following its publication in 1954, unaware of the fact that the seeds for those events and the massive consequences they entailed were sown in the 1940s, in Wertham's clinical experiences at Lafargue and his subsequent activity and way of thinking with regard to the late 1940s anti-comics drive. In order to fully understand Fredric Wertham's anti-comics agenda, this period needs to be taken into consideration. | |||

|

|||

| The

perception and evaluation of Fredric Wertham, his

motives and, above all, his modus operandi

have been the source of diverging opinions and

controversy since 1949. There were parts of the

public who applauded and supported him, and there

were others, including the scientific community at

large, who disagreed with Wertham both in terms of

what he seemingly wanted to achieve and his

methodology. Not surprisingly, neither the industry

nor comic book enthusiasts had any nice things to say

about Wertham - and for them the worst was yet to

come. When parts of the comic book industry took the

newly emerging genre of horror comics to extremes,

Wertham would return to the anti-comics movement in

1954 with a bang, and the fallout damage would prove

drastic and lasting. The discussion concerning comic books in the 1940s and 1950s took place in public and through the media. In assessing Fredric Wertham's role and ethics in this discussion, his public as well as his printed statements are therefore to be considered as the main source for answering that question. Comments and notes made in private may elucidate certain motives and procedural aspects, but apart from the fact that they were not available to researchers at large for an extraordinary long period of time, they were also not part of the public figure Fredric Wertham. Frederic Wertham continues to stir the interest of researchers, and in 2005 even found a sympathetic biographer in Bart Beaty and his Fredric Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture. |

|||

|

|||

| Interestingly, now that

the Wertham Papers are more easily accessible,

further research shows traits which would seem to fit

the image of the well-poisoner better: Carol L.

Tilley (2012) documents specific examples of how

Wertham not only overstated and compromised evidence

from his clinical research but actually manipulated

and fabricated data in order to serve as

"evidence" which he then attributed to his

personal clinical research with young people. Tilley

concludes that Wertham did this purely for rhetorical

gain. In the end, it all points to Doctor Fredric Wertham coming to see only what he believed to be right. Initially, he meant well. Ultimately, he himself betrayed all the principles he once stood for. |

|||

first posted to the web 7 May

2010 Text is (c) 2010-2014 Adrian Wymann The illustrations presented

here are copyright material. |

|||

BIBLIOGRAPHY BEATY Bart (2005) Frederic Wertham and the Critique of Mass Culture, University Press of Mississippi COVILLE Jamie (----) "The Comic Book Villain, Dr. Fredric Wertham M.D.", in Integrative Arts 10: Seduction of the Innocents and the Attack on Comic Books, available online and accessed 17 May 2010 at www.psu.edu/dept/inart10_110/inart10/cmbk4cca.html CRIST Judith (1948) "Horror in the Nursery", in Collier's Magazine, 27 March 1948 DECKER Dwight (1987) "Fredric Wertham - Anti-Comics Crusader who turned Advocate", originally published in Amazing Heroes (available online and accessed 12 July 2007 at www.art-bin.com/art/awertham.html) ELLSWORTH Whitney (1949) "Violence in the Comics - Reader's Letters", in Commentary 9 EVERSLEY Shelly (2001) "The Lunatic's Fancy and the Work of Art", in American Literary History (Vol 13, #3), 445-468 GABRIEL David Jay (2001) A brief history of first amendment issues in comic books, Ms.presented at the "Comics Code and Free Speech" discussion panel at the New York City Comic Book Museum, 2 October 2001 GILBERT James (1988) A Cycle of Outrage, America's Reaction to the Juvenile Delinquent in the 1950s, Oxford University Press HAJDU David (2008) The Ten-Cent Plague: The Great Comic-Book Scare and How It Changed America, Farrar, Straus and Giroux HAVERSTICK John (1957) The Saturday Review of Literature Treasury, Simon & Schuster INTROVIGNE Massimo (2003) "Fighting the three Cs: Cults, Comics, and Communists", Ms.presented at the CESNUR conference in Vilnius, 29 April 2003 LEE Stan & George Mair (2002) Excelsior! The Amazing Life of Stan Lee, Fireside MUHLEN Norbert (1949a) "Comic Books and Other Horrors - Prep School for Totalitarian Society?", in Commentary 7, 80-87 MUHLEN Norbert (1949b) "Violence in the Comics - Reader's Letters", in Commentary 8 MUHLEN Norbert (1949c) "Violence in the Comics - Reader's Letters", in Commentary 9 ROBBINS Trina (1999) A History of Women's Comics from Teens to Zines, Chronicle Books RYAN John (1936) "Are the Comics moral?", in Forum (95/5), 301-304 SCHULTZ H. E. (1949) "Censorship or Self Regulation?", in Journal of Educational Sociology (Vol. 23, #4), 215-224 SHERIDAN Martin (1942) Comics and their Creators, Ralph T. Hale & Comp. THRASHER Frederic M. (1949) "The Comics and Delinquency: Cause or Scapegoat", in Journal of Educational Sociology (Vol. 23, #4), 195-205 TILLEY Carol L. (2012) "Seducing the Innocent: Fredric Wertham and the Falsifications that helped condemn Comics", in Information & Culture: A Journal of History (47.4), 383-413 WERTHAM Fredric (1948a) "The Psychopathology of Comic Books - An Introduction", in American Journal of Psychotherapy (Vol 2, #3), 472-473 WERTHAM Fredric (1948b) "The Comics - Very funny!", in The Saturday Review of Literature (issue for 29 May), 6-10 WERTHAM Fredric (1948c) The Comics - Very funny!", in Reader's Digest (August issue), 15-18 WERTHAM Fredric (1949) "Violence in the Comics - Reader's Letters", in Commentary 8 WERTHAM Fredric (1954) Seduction of the Innocent, Reinhart & Company WITTY Paul (1941) “Reading the Comics - A Comparative Study”, in Journal of Experimental Education (#10), 105-109 WOMACK Michael T. (1992) Fredric Wertham - A Register of his Papers in the Library of Congress, Manuscript, Library of Congress, Washington (availabale online and accessed 26 March 2010 at www.governmentattic.org/2docs/LOC_Wertham-Papers_1992_2007.pdf) WRIGHT Bradford W. (2001) Comic book nation: the transformation of youth culture in America, Johns Hopkins University Press |

|||