|

| |

| |

COMIC PACKS

THE STORY OF THE ORIGINAL

COMIC BOOK IN A BAG

THE 1960s & 1970s

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| 1962 - A DOUBLE-EDGED YEAR

FOR THE COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY |

| |

| As the year

1962 rolled around, the US comic book industry found

itself confronted with a true dilemma. On the one hand,

it had done nothing less than re-invent itself as the

superhero genre - clinically dead for most of the 1950s -

had made a staggering comeback with the introduction of

new and instantly successful team titles (spearheaded by

DC's Justice League of America in 1960 and

Marvel's Fantastic Four in 1961), modernized

relaunches of Golden Age heroes (such as DC's Green

Lantern, Flash and Hawkman) and

new superhero characters (such as Archie's Fly

or Charlton's Captain Atom). There was a streak

of new creativity and enthusiasm throughout the whole

industry as it was poised to launch even more characters

which would enter and change comic book history. On the other hand,

the entire industry was looking to 1962 with apprehension

- for the simple and yet highly complex reason that for

the first time in the perceived history of comic books

the publishers were forced to raise their prices. Ever

since the 1930s, comic books had cost 10¢. In order to

hold that price, publishers had significantly lowered the

page count of their titles over the years to finally

arrive at only half of the original 64 pages comic books

had in the 1930s. This time, however, there was no way

around it, as rising production costs and inflation cut

too deeply into profit margins. But raising that cover

price was a psychologically difficult task to perform -

if too many readers would end up buying fewer comics then

the industry would ultimately lose more than it stood to

gain from the price increase.

Market

leader Dell jumped in first and headlong with a

staggering 50% increase from 10¢ to 15¢ in 1961 - only

to face desastrous results. The competitors held out for

a brief while, even capitalizing on the move by running

"still only 10¢" blurbs on their covers, but

eventually they all had to follow suit by early 1962 -

even though they only went up to 12¢. But this was still

a 20% price increase, and the drop in sales was brutal

across the board - DC Comics alone being rumoured to have

lost more than $600,000 in comparison to the previous

year (Wells, 2012); the statements of ownership required

by the US postal services show that the sales figures for

DC flagship titles such as Superman, Action

Comics and World's Finest dropped by around

25% in 1962 as compared to 1961.

At least the

industry had seen it coming, and some had planned on

several countermeasures. Some didn't work at all (such as

a loyalty scheme introduced by Dell), but DC Comics had

an idea which would prove to work out rather well: the COMICPAC.

|

| |

| INTRODUCING THE

"COMICPAC" |

| |

| The

intention was straightforward and made good business

sense - open up new sales opportunities and markets and

thus tap into a new customer base - and the concept which

followed from this was a fairly simple one: sell comic

books in packaged bundles as opposed to the classic

newsstand individual copy. The original idea was to combine four

different individual comic books using a sealed plastic

bag carrying a folded cardboard top as container, and on

November 30th 1961 National Periodical (i.e.

National Comics, i.e. DC Comics) submitted the name COMICPAC for trademarking.

|

| |

| The trademark was duly registered as

such by the US Patent Office on August 14th 1962 for the

purpose of producing, marketing and selling

"packaged comic books". Included in the

trademark was a graphic branding sign reading COMICPAC in shadowed

lettering which featured as the initial label and

visual tag both on the plastic bags themselves as

well as in in-house advertisements in DC's own

line of comic books. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| Intially

the readers' attention was drawn to the

new concept with a 1/3 page full-colour

ad ("HAVE YOU SEEN THE

NEW COMICPAC")

which appeared, amongst other titles, in Blackhawk

#175 and Strange Adventures

#143, for the August 1962 cover date

production run. The ad is interesting

because it doesn't even clearly state

what a Comicpac is - this had to be

deduced by the reader from the

illustration of one, showing the cover of

the at the time current issue of Action

Comics.

Instead of

actually explaining the product, DC

emphasized where it could be purchased:

at supermarkets.

|

|

In-house

ad from Blackhawk #175 (August 1962) for

DC's "new" COMICPAC,

featuring a bag containing Action Comics

#291 (August 1962)

|

|

|

| |

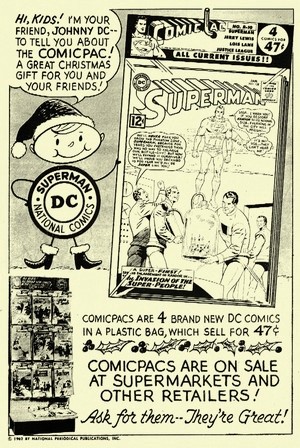

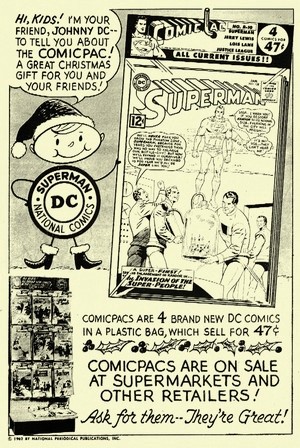

| A second in-house ad, which

ran in a number of DC titles of the January and February

1963 cover month production (and which thus was just in

time for Christmas as the cover month was usually about 3

months ahead of the actual publication date) took up a

full page, was placed on the inside cover, and explained

in much more detail what the Comicpac was all about. |

| |

In-house

ad from the inside cover of Detective

Comics #311 (Januuary 1963) for DC's

"new" COMICPAC,

featuring a bag with Superman #158

(January 1963)

|

|

The ad featured newly

introduced mascot "Johnny DC"

who pointed out the Comicpac as a great

Christmas gift to readers of e.g. Detective

Comics #311

(January 1963), Strange

Adventures #148 (January 1963), Rip

Hunter - Time Master #12

(January-February 1963) Action Comics

#297 (February 1963), Superman's Girl

Friend, Lois Lane #39 (February

1963), and Tales of the Unexpected

#75 (February-March 1963). This time it was

explained that a Comicpac was a plastic

bag holding four brand new DC comics and

that they sold for 47¢

(which the regular comic book reader knew

was one cent less than what you'd pay for

four individual issues), but the emphasis

once again was on their point of sale:

supermarkets (and other retailers).

Today, the attention

of many comic book fans seems to be drawn

to the price (on those rare occasions

when comic packs are discussed in online

fora), and many seem to mistakingly think

that what was essentially simply a price

tag was a discount advertising and even

the driving idea behind the Comicpac

concept.

In reality, the one

cent discount would obviously have been a

very weak selling point. Accordingly, DC

never even pointed that out (the

prominent blurb on the bag simply stated

the price of the Comicpac and the number

of comics you got), not the least because

that minimal saving would often be erased

anyway by the fact that comicpacks could

be subject to sales tax at the

supermarket check-out (Evanier, 2007a).

|

|

|

| |

| Besides - offsetting the

losses in sales caused by the 1962 price increase by

trying to sell 4 comics for a discount of one cent would

have been a hopeless idea. But compensating the downturn

in the established customer base by tapping into a new

one was most definitely something which could work and

help alleviate - or even turn around - the situation. The primary idea DC

was thus pursuing with its Comicpac was to break into new

sales opportunties and reach a customer base which, for

one reason or another, simply didn't buy comics off the

newsstand or spinner racks. And one place these

individuals could be found were the growing number of

supermarkets and chain stores.

|

| |

| THE MAGIC WORD: PACKAGING |

| |

The comic book industry was

faced with a growing problem: they were offering a

commodity which proved increasingly cumbersome to receive

and handle - and which yielded only marginal profits with

sales at a price of 12¢ per item. Furthermore, the comic book's traditional retail

outlets - small community stores and newsagents - were

increasingly giving way to larger stores which were not

interested in selling comics. The number of distribution

outlets was shrinking, and the distribution system per se

did nothing at all to counteract this development - on

the contrary.

"A few

retailers actually liked carrying comics, but most

were indifferent. Comics weren’t after all, an

absolute necessity to most retailers who sold

periodicals, in the way that Cosmopolitan, Playboy,

Time and Sports Illustrated were. So, let’s say

[the local distribuor] actually delivered 5,000

copies [of 10,000 received at the warehouse] to the

retailers. If they bothered to deal with

unwrapping and sorting, if they had room on the

trucks… Most likely, they’d only

actually deliver comics to retailers who would

complain if they didn’t get comics and places

that sold enough comics to make the driver’s

effort worthwhile." (Shooter, 2011)

|

| |

| In stark

contrast to the comic book's

historical sales venues,

supermarkets were booming. They

were popular because they sold

many different things under one

roof - and evidently, comics were

not amongst the merchandise they

carried. In order to

change this, the whole concept of

selling comic books had to be

revised. Handling individual

issues clearly was no option for

these outlets, but by looking at

their logistics and display

characteristics DC found that the

answer to breaking into this

promising new market could be - a

simple plastic bag.

Packaging

defined the Comicpac in the first

place, but it was also its magic

word which opened the doors of

the supermarkets to DC's comic

books.

Putting

four comic books into one

container resulted in a higher

price per unit on sale (47¢ rather

than just 12¢), which made

the whole business of stocking

them much more worthwhile for the

seller. The simple packaging was

also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new

and untouched, which in turn did

away with individual comic books

starting to look tatty after a

dozen individuals had taken them

off the rack, thumbed through

them, and placed them back again,

often with little to no care.

Packaged

in plastic bags, DC's comic books

literally blended in with a large

proportion of other goods sold at

supermarkets - also conveniently

packaged.

|

|

Various unused plastic bag

packaging for DC and Marvel

comicpacks from the 1960s

|

|

|

|

| |

| Presented this way, comic

books became sellable to supermarket shoppers - giving DC

access not only to new market opportunities, but to a

whole new customer base. |

| |

| HEY (GRAND)PARENTS - COMICS ! |

| |

The

intention of tapping into the growing number of

supermarkets and chain stores as a potential sales ground

was tied to a very specific type of target customer:

"DC's

focus [for the Comicpac] was on both the casual

reader and the parents and grandparents who were

looking for gifts." (Wells, 2012)

This becomes

even clearer if you take a closer look at DC's packaging

concept for the Comicpac. By putting four comics into one bag,

only two covers were visible. Initially, the bags would

identify which titles were enclosed (though not the issue

numbers) so that buyers knew more or less what they were

getting, but when the number of comic books contained in

a comic pack was reduced to three at the beginning of the

1970s, this information was dropped.

|

| |

This

effectively turned the comic book in the middle

into a "mystery" surprise issue - and

as surprises go, they can be good or bad, and it

is precisley this element which made regular

comic book readers shy away from that comic book

bundle in a plastic bag.

"[They]

passed on the bagged comics since there was

usually at least one issue that they didn't

want or need." (Wells,

2012)

"I had

so many comics, the odds were I'd wind up

with dupes (...) that was why Comicpacs did

not work for me. Insofar as I could tell,

they didn't work for anyone."

(Evanier, 2007a)

Evanier's concluding

assumption is - as he himself was quick to point

out (Evanier, 2007b) - wrong. The Comicpac

actually worked just fine - for casual readers or

people not buying comics for themselves (such as

parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts).

The display sign

mounted above the Comicpac display rack read

"kids" - but really meant their parents

The fact that it

didn't work that well for avid readers lies with

the very principle of the Comicpac: packaging.

For obvious reasons the regulars didn't want

their comic books in a bag where they couldn't be

100% sure what they were buying. But the idea of

the Comicpac wasn't to annoy that customer base,

but rather to tap into a new one.

|

|

A dedicated

display rack for DC Comicpacs

|

|

| |

| And to those individuals,

the packaging actually held the added appeal of being

rather neat, doing away with having to deal with a bundle

of loose comics, and the sealed plastic bag made it look

much more sophisticated as a gift. Specific content was

of no real concern to the casual buyer as long as you had

a general idea of what you were getting, and DC even

provided stores with a dedicated display rack system. In

addition, the Comicpacs made sure that the selection

covered a wide range of genres - superheroes, funnies,

romance, western. And

finally there were those comic book readers who simply

did not have access to outlets who sold comics and

regularly restocked. To them, the Comicpac could more or

less be the only way of getting hold of comics at all.

|

| |

|

| |

Strategically placed close

to checkouts and cash points, DC's comic packs were a

success.

"The DC [comic

packs] program lasted well over a decade, with pretty

high distribution numbers. The Western program was

enormous - even well into the '70s they were taking

very large numbers of DC titles for distribution (I

recall 50,000+ copies offhand). The unknowable factor

on the DC program was that a certain number of

distributors and retailers simply split the packs

open and returned the loose comics, making an

arbitrage profit, and distorting the flow of actual

sales data so it looked like the packs sold near

100%. There was no clear pattern of these

"arbitraged" copies depressing the sell

throughs of the regular releases for most of those

years, though, until towards the end of the

program." (Paul Levitz, in Evanier (2007b))

Levitz is refering to the

fact that comic packs, unlike comic books distributed to

newsstands and other traditional outlets, were

non-returnable. Bags which didn't sell were thus the

seller's problem, not the publisher's.

|

| |

|

|

As such the

Comicpac was one of the first

attempts by DC to work their way

out of the traditional but

increasingly unprofitable setup

of reimbursing resellers for

unsold items - a business

model which of course did nothing

whatsoever to encourage actual

sales.

As an

example, Detective

Comics #433 (March 1973,

included in DC's 1973 D-3

Super Pac) carries the

required annual statement of

ownership and circulation, which

shows that whilst DC printed an

average of 332,000

copies per issue of Detective

Comics per month in

1972, only 158,638 of these (i.e.

less than 50%) were, on average,

actually sold.

|

|

|

|

| |

| And it wasn't just DC:

Marvel saw 65% of all copies distributed

throughout the 1970s being returned - and sometimes even

reimbursed without any physical proof (Groth, 2006). But

even if the traditional upper half of the cover was

returned it didn't stop some resellers from making an

extra profit by selling coverless comics. Just as the

comic packs didn't stop

anyone from ripping open the bags and returning the

individual comic books which hadn't sold as Comicpacs -

ultimately leading to specially marked covers as of the

late 1970s to counteract this fraudulent practice. The

comicpacks were thus also a first example of trying to

create something akin to what would eventually become the

direct market, where specialized comic book resellers

would get better deals but on a base of

non-returnability. |

| |

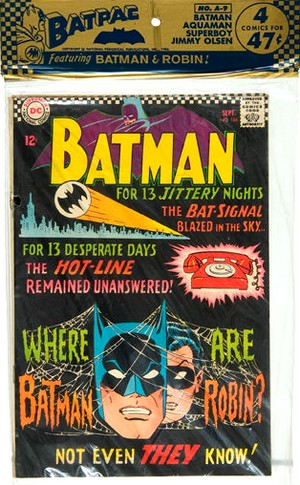

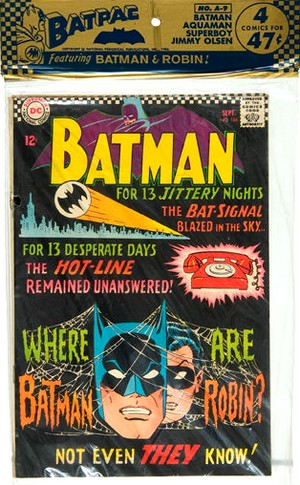

| Regardless of

these problems, Comicpacs sold

well. And when ABC launched its

Batman TV series in January 1966

and the show became an overnight

surprise sensation - "completely

burying the competition"

(Gerani & Schulman, 1977) - the comic

books in DC's plastic bags became

even more mainstream and sellable

- so much so that for a short

time DC even rebranded some of

its Comicpacs as BATPACs in an

attempt to hook onto the 1966/67

Batmania and all of its

merchandising craze. It really

was the show that turned Batman

into the popular culture icon he

still is today, and into a mighty

point-of-sale for DC at the time:

the "exposure the show

brought to the comics was

enormous" (Dixon,

2010), and sales of Batman

soared to 900,000 monthly copies

in 1966. By that time,

the Comicpac had already

successfully achieved what DC had

set out to do - to get comic

books sold in supermarkets. But

other than that - how successful

were these plastic bags overall? There are two

highly reliable indicators for

judging whether or not a business

or product idea is a success or

not: if it can generate and boost

demand, and if it leads to others

wanting to do the same thing.

The Comicpac

had successfully opened the doors

to supermarkets and chainstores

for DC comics, and in doing so

brought National Periodical into

direct contact with a company

which had accomplished a similiar

market entry 50 years earlier: in

1918, Western Publishing persuaded the

Woolworth Company to place

children's books on display in

its retail stores all year round,

something which previously had

only been done during the

Christmas season (biglittlebooks.com).

|

|

Batpac

A9 with Batman #184 (September

1966)

|

|

|

|

| |

| The public’s response

was so enthusiastic that Western developed a line

designed for a year-round market, and its success lead

Western to establish a separate book division for this

market: Whitman Publishing. |

| |

| 1967 - ENTER WHITMAN |

| |

| With established

connections to chain stores, Whitman gained a strong

presence in the form of large shelved display spaces. The

range began to extend beyond books to boxed games and

jigsaw puzzles, but the real ace product was the Big

Little Book® introduced in 1932. |

| |

|

|

Whitman also

pioneered the licensing of comic

characters for various

publications (including the Big

Little Books) and entered into a

successful and ultimately

long-standing relationship with

Walt Disney Productions. In 1933

Western/Whitman secured exclusive

book rights to all the Walt

Disney licensed characters, and

in 1937 took over production and

publication of the popular Mickey

Mouse Magazine. Opening

offices in Poughkeepsie NY in

1935 entailed a close association

between Western and Simon &

Schuster as well as the Dell

Publishing Company, the latter

introducing Whitman ("kid

tested") to the comic market

proper (biglittlebooks.com), and it was

this backing through the finely

tuned distribution and display

presence of Whitman which made

Dell the number one comic

publisher - until the 1961 cover

price rise.

|

|

|

|

| |

| It was

therefore only a question of time that National

Periodical's successful strategy of introducing and

selling packaged DC comic books to supermarkets would

bring them into contact with Whitman - just as it was

only a matter of time before other publishers would start

to copy DC. It is evident that both companies could

easily profit from each other, and if National Periodical

could profit from Whitman's distribution and sales

network then that would more than make up for the

impending loss of the monopoly of the Comicpac. So in

1967 Whitman took over the distribution not only of DC's

comics, but of those of a quickly growing number of

additional publishers (McClure, 2010) - who wanted to

have a share in DC's successful Comicpac business scheme.

|

| |

|

| |

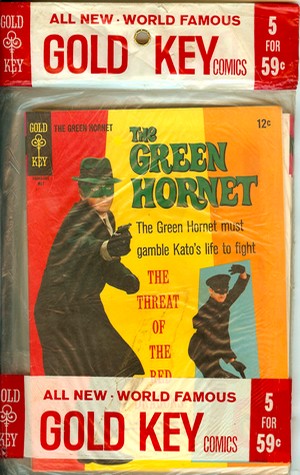

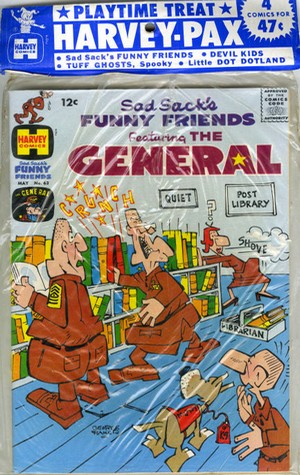

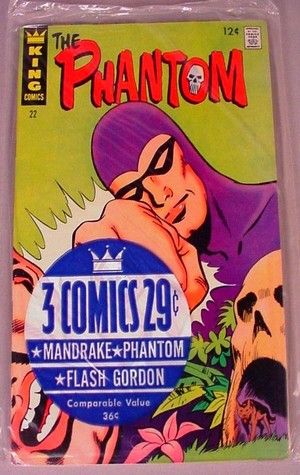

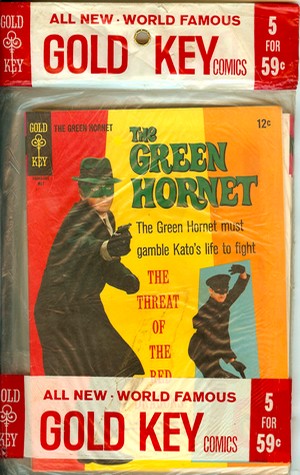

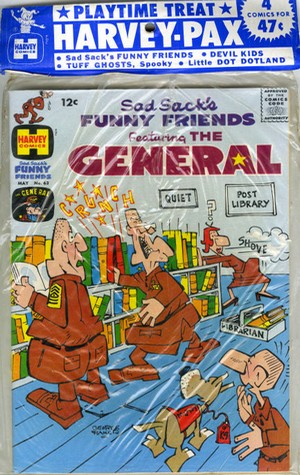

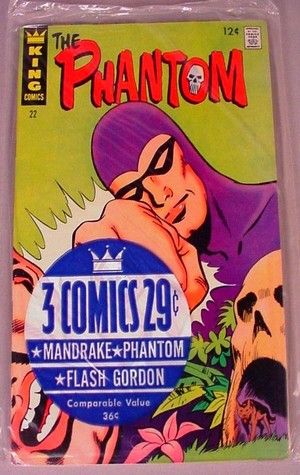

| Both

products could be displayed in absolutely the same way as

DC's Comicpac - not so the very austere three-pack from

King, which had no product name and just carried a

sticker on what was almost a shrink wrap which lacked the

hanger for a rack display. But unlike the competition,

King indicated the comparable value of the three

individual comics (36¢) and offered a far

"bigger" discount in comparison: 7¢ as opposed

to the one cent of the various other publishers (although

DC even put out a few comic packs in the late 1970s

without any saving at all). This points to the fact that

DC's Comicpac had paved the way for bagged comic books

into supermarkets and chain stores, so a new publisher

such as King (established in 1966) could at least try to

gain a slightly bigger piece of the cake (i.e. the

established new market) through pricing. It didn't work

for King, the very short-lived comic book imprint of King Features Syndicate,

which was set up to publish their syndicated characters

in their own range of comics (rather than as licensed

properties) - King Comics was shut down again by the end

of 1967. |

| |

Packaged

comics from Gold Key, Harvey, and King - all 1967

|

| |

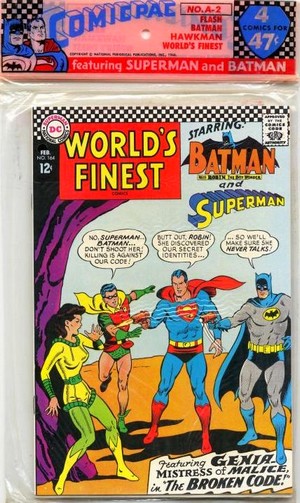

| At around the same

time in 1967, DC's Comicpac cardboard header

(which, as unopened bags from that era show,

could become quite tatty) was replaced by

printing directly onto the bag, soon to become a

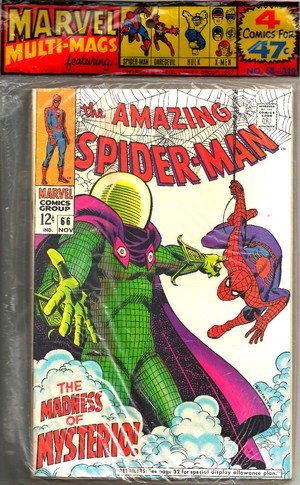

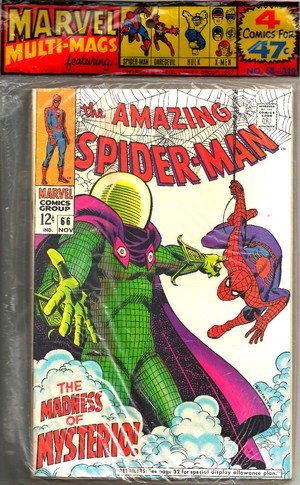

general feature of all comic packs. Successful

and innovative Marvel Comics had just grabbed the

market leader position from DC in early 1967, and

the House of Ideas tuned in on the Whitman

distribution deal to supermarkets and chain

stores too, labelling its four-packs MULTI-MAGS and using

the character vignette in a box (Steve Ditko's

brainchild) to help buyers who were in the know

identify quickly which titles they were getting.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| To all other

buyers - the aformentioned

parents, grandparents, uncles and

aunts - it probably didn't matter

anyway as long as they could see

and understand that they were

getting some Spider-Man. Whilst

basically picking up a business

idea from the "distinguished

competition" - as Stan Lee

would call DC after Marvel

overtook them in monthly sales

(prior to that DC had been

"Brand Ecch", i.e.

Brand X) - Marvel was at the same

time looking into other ways of

fighting the losses incurred by

the already mentioned system of

returnability.

Interestingly

enough, one such attempt has been

preserved in the time capsule of

a Multi-Mag, namely 68-A10, where

the cover of Amazing

Spider-Man #66 (November

1968) carries a blurb at

the bottom reading

"RETAILERS: See page 32 for

special display allowance

plan". Turning to page 32

revealed that retailers would

receive a 10% payment for all

Marvel comics sold (which would

have been 1,2 cents per regular

comic).

The

scheme does not appear to have

been a huge success, but it

graphically illustrates how

crooked and therefore both

unpredictable and unprofitable

the system of returnability had

become for comic book publishers,

who were increasingly looking for

alternatives as a way out.

Unlike

what many comic book fans

possibly thought at the time (and

even today), the comic packs were

a lone success story on that

playing field.

|

|

Marvel

Multi-Mags A10 with Amazing

Spider-Man #66 (November 1968)

|

|

|

|

| |

| Marvel, rather

surprisingly, dropped out of the comicpack market

in mid-1969 when the sale of the company to

Perfect Film resulted in a switch of both

printers and distributor, the latter being Curtis

Distribution (also owned by Perfect Film and

hence in-house) who replaced Independent - and

the Whitman distribution deal simply expired

alongside (cf. THOUGHT

BALLON #43). |

| |

| THE 1970s - THE

SUCCESS STORY CONTINUES |

|

| |

| With the benefit of

hindsight it is not difficult to see how DC's Comicpac

and its close cousins were a first step in going to where

the comic book industry would eventually find it's

survival lifeline: the direct market. |

| |

|

|

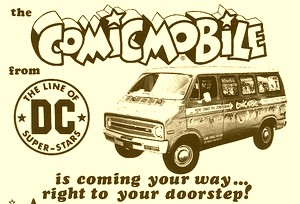

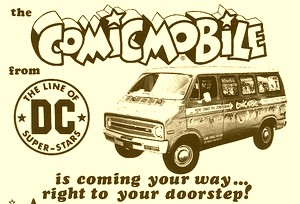

DC had other

"direct market ideas"

too, but most remained embryonic

and didn't really work out, just

like Marvel^s retailer allowance

plan. One of the most amazingly

fantastic attempts at tapping

into the market by selling comics

outside the newsstand

distribution system must have

been the Comicmobile. The

brainchild of DC's vice president

and production manager Sol

Harrison, it briefly toured the

NYC suburbs during the 1973

summer school break, sporting the

slogan "HERE

COMES THE COMICSMAN", and

stocked with surplus comic books

from the DC library.

The

end, however, came quickly.

|

|

|

|

| |

"When school

started, the Comicmobile’s hours of operation

were severely reduced (...) I’m sure part of it

also had to do with the fact that we were barely

making enough to cover the cost of gasoline the van

was guzzling… and gas was only 20c a gallon at

the time! The Comicmobile was shipped off to comics

dealer Bruce Hamilton out in the southwestern U.S.

for continued "testing." The entire

project, however, met an untimely end when the

Comicmobile came out on the losing end of a collision

with a semi." (Rozakis, 2010)

|

| |

| Again, this

only goes to show just how

successful the comic packs were

in comparison, and as the decade

which had seen the creation of

the Comicpac gradually came to an

end, more and more comic books

found their way into plastic bags

and then on to some supermarket

or chain store. As the 1970s

rolled around, an important

change took place - Whitman not

only took care of the

distribution and sales end of

things, but also started to get

involved in the packaging and

publication process itself. By

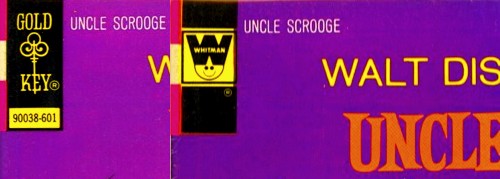

1972 Whitman was selling comic

book packs containing Gold Key

titles which had their logo

replaced by the familiar Whitman

face logo.

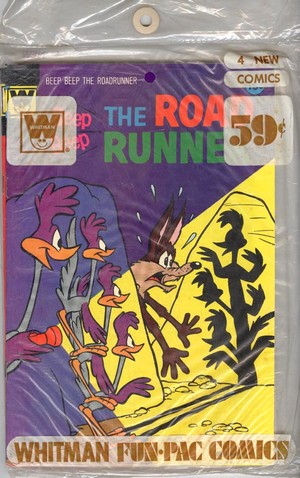

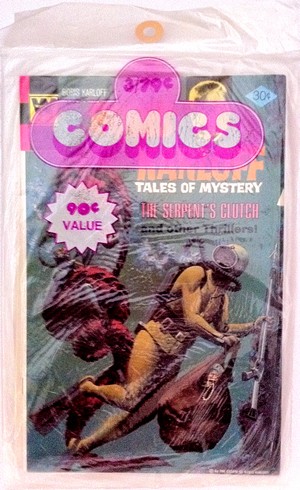

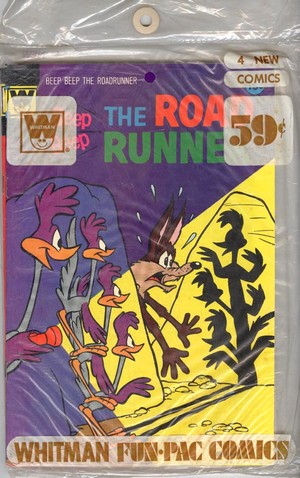

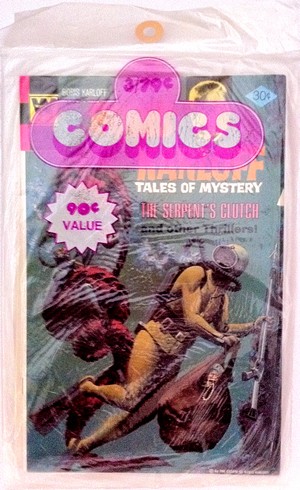

Initially

comprising of cartoon characters,

the Whitman comic packs were

branded as WHITMAN

FUN-PAC COMICS as of 1973.

Soon however the bags would also

hold other Gold Key licensed

property comics with a Whitman

logo, although these bags would

not carry a specific Whitman

marking (as seen with a three

pack featuring Boris Karloff

Tales of Mystery #70,

published in September 1976).

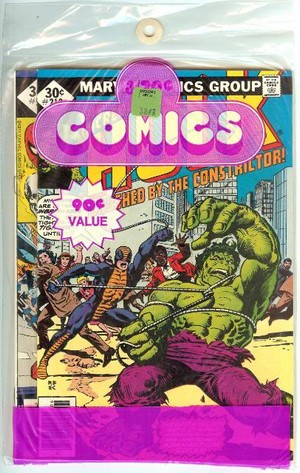

Sometimes these same bags would

also be used to hold Marvel comic

books - the example here comes

from 1977 - even though Marvel

still had its own Multi-Mags

programme at the time.

|

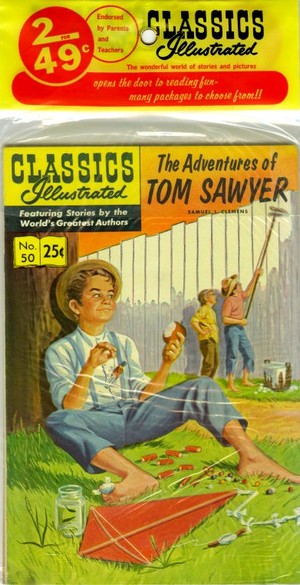

|

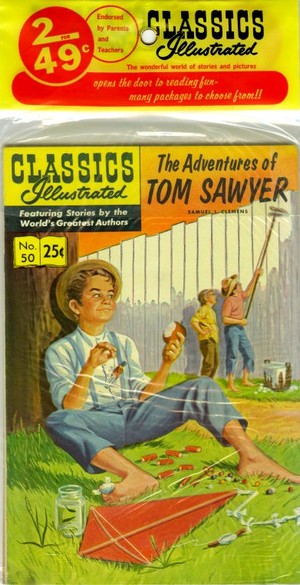

Classics

Illustrated two-pack from 1969

|

|

|

|

| |

| By 1975 Marvel was back in

the comicpack business, both with their own MARVEL MULTI-MAGS as well as bag packaged and

distributed especially through the Whitman network - and

these were actually the very first direct market editions

(bought by Whitman at a more favourable price than

newsagents could, but without the right to return unsold

copies). They were absolutely identical to their

newsstand edition cousins save for the white diamond in

black box containing the issue number and price (McClure,

2010). |

| |

|

| |

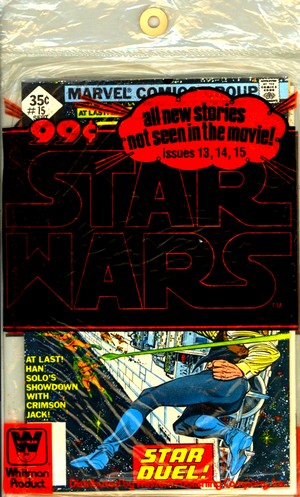

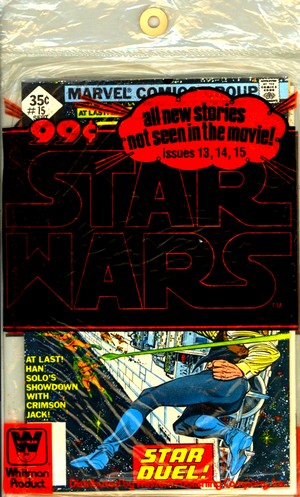

| Then, as of 1977, Whitman

would also start to sell specific comic book titles from

Marvel in bags clearly marked "Whitman" after

Marvel took to licensed adaptations of science fiction

movies as of 1977. |

| |

|

|

Spearhead

by the phenomenally

successful Star Wars

- which Whitman sold

packaged bundles of three

issues with continuous

numbering - these comic

packs also featured Battleship

Galactica or the Micronauts

- and as such never

contained mixed titles. Whilst

these comic packs carried

the Whitman Logo and a

branding

"Distributed by

Western Publishing

Company Inc.", the

inventor of the Comicpac

- DC Comics - still

offered its own comics in

packaging clearly marked

DC (alongside

"themed"

Whitman DC bags, e.g. 3

Superman comics in one

bag, with the DC bullet

logo replaced by the

Whitman roundel). The

name had changed from COMICPAC to SUPER PAC in

1970/71, but it was still

done to the same success

formula. By 1972 a DC

comic pack would as a

general rule (there were

exceptions) contain three

comic books, two of which

were visible on either

side of the plastic bag,

and one stuck in the

middle which sometimes

could be glanced, and

sometimes not.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

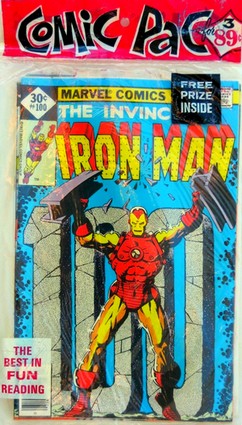

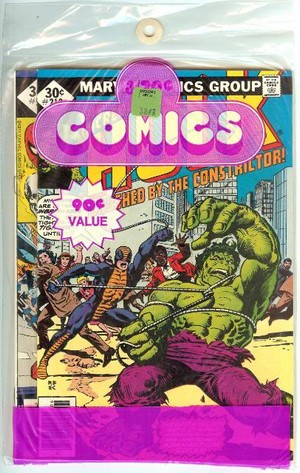

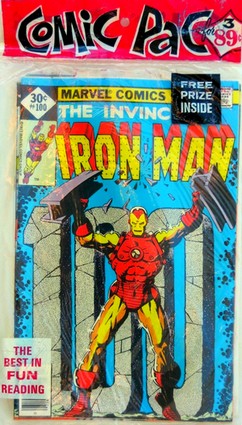

| Marvel was using different

distribution channels as well - sticking to their MULTI MAGS they also saw all the major

characters from the Marvel Universe sold in Whitman bags

(bearing the already mention white diamond in black

square). |

| |

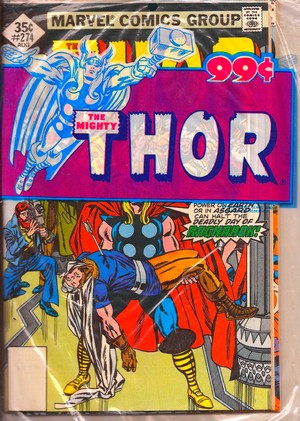

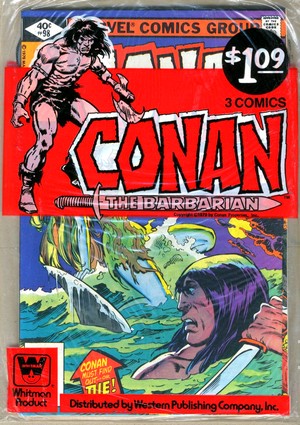

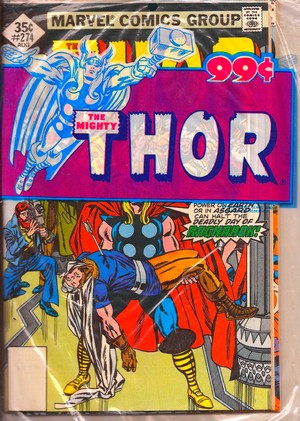

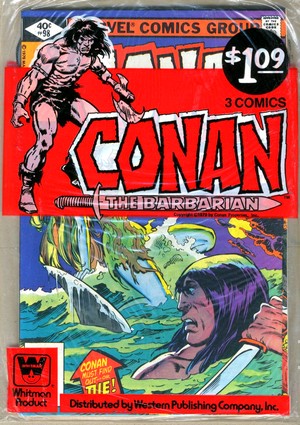

| Probably

based on the success of the dedicated Star

Wars comic packs, Whitman started to

offer character themed bags which

typically featured three consecutives

issues of one title. These were clearly

marked, as can be seen from the Thor

(1978) and Conan (1979) examples below.

|

|

1977 "Comic Pac" with Marvels

Far left: Thor Pack from 1978

Left: Conan Pack from 1979

|

|

|

| |

| THE

SYSTEMATICS OF DC's COMIC PACKS |

| |

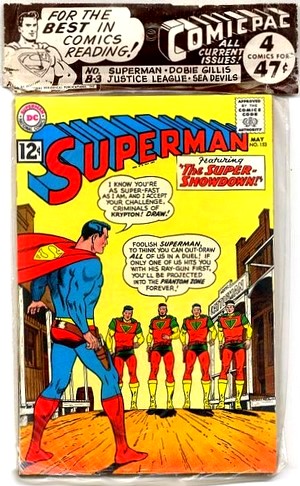

| When DC Comics

launched the Comicpac in 1961/62 they

went about setting up their new packaging

and sales concept in a very methodic way

- one aspect of which was that all of

DC's multi-comic packs were reference

numbered right from the start. |

| |

|

|

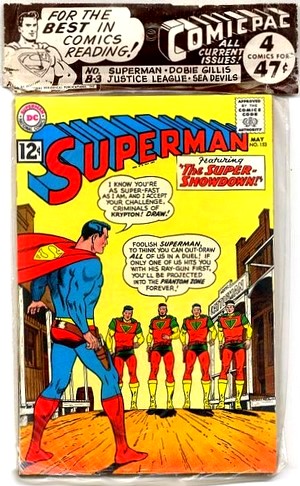

Comicpac

B3 from 1962, with Superman #153

(May 1962) as its showcased title

|

|

This

translated into a code using a

letter plus digit - for example,

the Comicpac pictured here is the

"B-3" pack from 1962.

Rather than just filling the

plastic bags at random with any

four comic books (initially all

placed with their cover facing

the same way, so that one side of

the plastic bag would only show

the ad on the outside back

cover), the Comicpac was thus a

clearly defined commodity, and

the 1962 B-3 pack would thus

carry the same four issues no

matter where or when it was sold.

Interestingly

enough this also means that

someone somewhere had to make the

decision which comics went into

which Comicpac. Little to no

information on this seems to be

publicly available, leaving open

to speculation the question

whether the selection was driven

by surplus stock or conscious

title selection. Whilst probably

a mix of both, there does seem to

have been a tendency to include

certain popular or iconic

characters and their books.

Throughout

the 1960s there were a total of

24 sets of Comicpacs per year,

coded A and B respectively and

numbered 1 to 12. By 1964 the

digit would refer to the month,

i.e. A-1 and B-1 would both

feature comic books with a

January cover date (or

January/February in the case of

bi-monthly titles) - a code

system which Marvel initially

also adapted for its Multi-Mags,

whilst other publishers would use

it in a fairly on/off way for

their comic packs.

It is hard to

tell if the casual buyers even

paid any attention to DC's neat

code system, but it is an

indication of how organized and

structured the comic packs

business at DC was. Marvel, on

the other hand, dropped codes all

together in the early 1970s, and

as a result there is no

systematic indication of how many

different Multi-Mags the House of

Ideas was releasing during the

1970s.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Just how

successful the Comicpac concept really was and how well

it worked for National Periodical is reflected in the

fact that after around 10 years of market presence, DC

doubled the number of comic packs packaged per year. By

1972, four packs were distributed each month, resulting

in a total of 48 sets per year, coded A to D and 1 to 12.

There even were extra runs at times, given the code EE. |

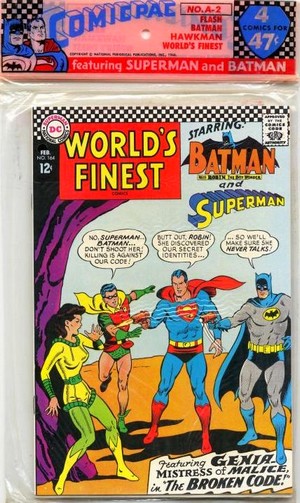

| |

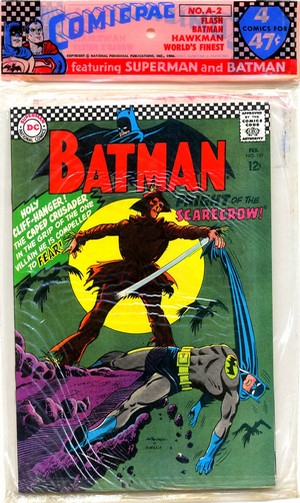

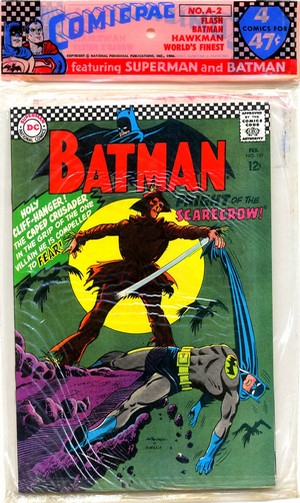

Two sides to a Comicpac (left and center): back and front

(you get to chose which is which) showcase covers of

Comicpac A2 from 1967,

with Batman #189 (February 1967) and World's Finest #164

(February 1967).

And then the Comicpac became the Super Pac in 1970/71

(right), A-12 showcased Superman #246 (December 1971)

|

| |

| By 1977, the DC Super

Pac briefly became DC Dynamite Comics and

then DC Dynamic Comics as of 1978. The high time

of the comic pack was over by the end of the decade for

all publishers, but various incarnations would be seen

throughout the following decade as the original comic

book in a plastic bag began to trickle out. Whitman

stopped distributing and selling comic packs with Marvel

and DC comics in April 1980. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY DIXON Chuck (2010) "Known

Super-Criminals still at Large: Villainy in Batman",

in Gotham City 14 Miles: 14 Essays on Why the 1960s

Batman TV Series Matters (Jim Beard ed.), Sequart

Research & Literacy Organization

EVANIER Mark (2007a) "It's in the Bag!", published online in News

From Me

EVANIER Mark (2007b) "More on Comicpacs", published online in News

From Me

GERANI Gary & Paul H.

Schulman (1977) Fantastic Television, Harmony

Books

GROTH

Gary (ed.) (2006) The Comics Journal #277 (July

2006), Fantagraphics

McCLURE

Jon Martin (2010) "A History of Publisher

Experimentation and Variant Comic Books", in Overstreet

Comic Book Price Guide, 40th Edition, Gemstone

Publishing

ROZAKIS

Bob (2010) "The

Comicmobile", published online at Anything

Goes (Bob Rozakis Blog)

SHOOTER

Jim (2011) "Comic Book

Distribution", published online at jimshooter.com

WELLS John (2012) American

Comic Book Chronicles: The 1960s (1960-1964),

TwoMorrows Publishing

|

| |

|

| |

First

posted to the web 19 December 2013

Revised, updated and reposted 14 April 2014

Last updated 1 June 2016

Text

is (c) 2013-2016 A.T. Wymann

The illustrations presented here are copyright material.

Their reproduction in this non-commercial context is

considered to be fair use.

|

| |

|

|

| |