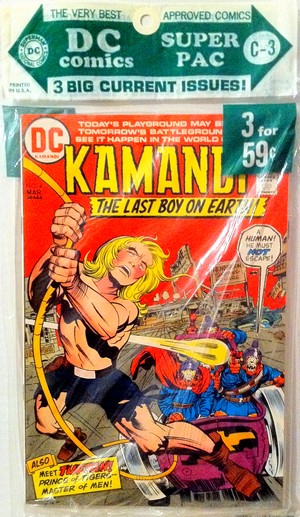

KAMANDI, STRANGE ADVENTURES & SUPERMAN'S PAL JIMMY OLSEN INSIDE THE |

|||||

|

|||||

Kamandi #4 - Strange Adventures #241 - Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #157 |

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

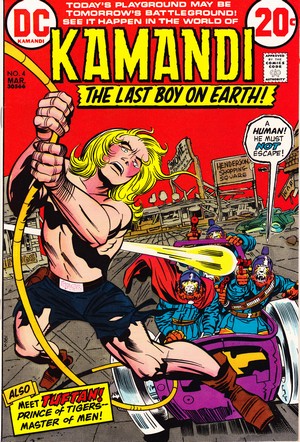

| This is the

fourth installment in a concept which was a great

framework for presenting stories which were at the same

time almost stand-alone and yet set in a developing

overall saga. Kamandi certainly was an ideal

candidate for the comic packs, and was included regularly

- which also goes to show that DC's Super Pacs of the

1970s were far from being collections of leftover poor

sellers. Although "under-appreciated in its time (...) the sprawling, innovative series

is a real gem, one of the most creative and underrated

comics of the 1970s, and perhaps the best of Kirby’s

DC canon" (Parker, 2011). It was, in any case,

the longest running of Kirby's DC titles, lasting from

October 1972 to September 1978 over the course of 59

issues before falling victim to the infamous DC

Implosion. Right from the start the fact that Kamandi's overall concept was so strongly reminiscent of the Planet of the Apes movie lead to accusations of Kirby having plaguarized the movie - when in actual fact he had already come up with those conceptual ideas in the 1950s. But using the famous Statue of Liberty scene from the movie on the cover of the first issue didn't help in any way, and the letters page of this issue contains two missives bringing up said accusation. Wikiepdia and other websites claim that when Carmine Infantino could not secure the rights to the movie for DC he told Kirby to come up with a "piggyback concept"; this information is, however, unsourced and could therefore just be a (more or less informed) guess. The appreciation of "The Devil's Arena" will to no small extent be tied to the reader's general appreciation of Kirby, but even for those who are not overly enamoured with his style (both in terms of storytelling and artwork) this is an entertaining little piece of early 1970s comic book history. |

|||||

|

|||||

| Originally home to feature

characters such as Captain Comet, Star Hawkins, and the

Atomic Knights, Strange Adventures had initially

been a science fiction anthology title with these regular

protagonists, but was turned into a supernatural-fantasy

title once past the 200 issues count and featured the

first appearance of Deadman in Strange Adventures

#205 (October 1967), who went on to be the title's main

character (with some early Neal Adams artwork) up until

issue #216. As of Strange Adventures #217 and

together with a logo change, the book became a reprint

title featuring Adam Strange in stories originally

published some ten years earlier in DC's other

long-standing sci-fi adventure title Mystery In Space

(one sole new original story written by Denny O'Neil was

featured in Strange

Adventures #222). Adam Strange, co-created by Julius Schwartz and Gardner Fox with Murphy Anderson, made his debut in Showcase #17 (November 1958), DC's tryout title, before ultimately moving to a permanent slot in Mystery in Space for almost fifty issues. Mostly written by veteran Gardner Fox and pencilled by Carmine Infantino, Adam Strange is a human from Earth who repeatedly travels to a planet called Rann, located in the Alpha Centauri star system, by using a "Zeta-beam" altered by "space radiation".

In "The Cloud Creature That Menaced Two Worlds" Adam Strange fights Alva Xar, a former warlord who after having slept a 1,000 years is intent on conquering Rann and reigning supreme. The cloud creature is formed by a special weapon which Xar uses (one on Earth, one on Rann), and whilst it nearly spells the end of Strange on his home planet, it proves the downfall of Xar as in its presence all life stops in its tracks save Adam Strange. Just why this happens to be so is left unexplained, along with one or two other holes in the plot logic, but then such things can almost be considered a trademark of Gardner Fox, who back in 1939 introduced some of the most iconic Batman gimmicks but at the same is responsible for probably the worst Golden Age Batman stories of them all.

The art by Carmine Infantino, however, makes it easy to overlook those shortcomings as the whole story has a "classic" feel to it - as indeed befits a 1960s period piece. Oddly enough, the letters page (actually half a page) is concerned with the question who might write and draw new original Adam Strange material - whilst the title was only three issues away from cancellation. In 1978 DC Comics intended to revive Strange Adventures, but the "DC Implosion" with its sweeping cancellations and scaling back of the company's publishing output put those plans on ice. Eventually the revival did happen, in 1979, and with a change of title to Time Warp. Always an interesting item, this issue of Strange Adventures prints the statement of ownership and circulation: of an average of 275,000 copies printed per issue per month during the preceding twelve month period, some 135,676 of these had actually been sold - i.e. only 49,3% on average. This is an awful figure showing just how bad the distribution situation in the early 1970s was. Surprisingly enough, closest to the filing of the statement Strange Adventures had an even higher print run (353,000), of which, however, it sold even less, namely 47,3% (equaling 166,821 copies). The number of subscribers to Strange Adventures at that point, by the way, was a mere 59 - up from an average of 30 over the past 12 months. Which makes it seem very - pardon the pun - strange that DC even carried subscriptions for this title. |

|||||

|

|||||

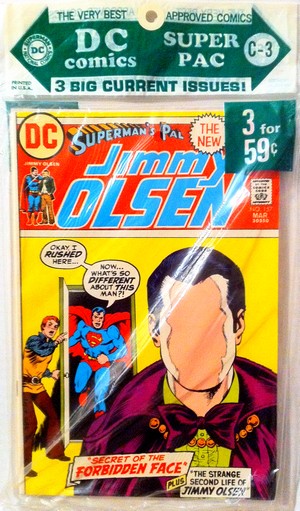

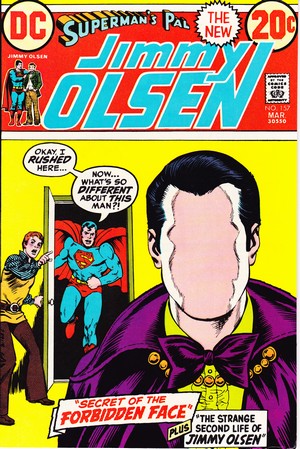

| The famous Star of Cathay

jewel is the feature of an exhibition in Metropolis and

it's Jimmy Olsen's job to take a picture of it - however,

when he does, the gem seemingly transports his

consciousness to ancient China, where all points to Jimmy

being none other than Marco Polo. Even meeting a magic

djinn in a bottle, Jimmy is drawn into a series of

increasingly threatening adventures, but just before he

is about to get killed he is sent back to the present

time and location, leaving him utterly confused and not

knwoing which reality is actual reality and which is a

dream. In the backup story, Jimmy Olsen is told by his

editor to get a clear portrait photograph of Mr Vargas,

an elusive master mentalist whose face never shows up in

pictures of him. Vargas uses his powers to stop some

crimes, which in turn makes him a target for paid

assassins but then Superman swoops in and saves the day -

and discovers the secret behind Mr Vargas. The

mentalist's face is horribly disfigured and he uses

mental powers which not only keep anyone from noticing

his face but also prevents photographic film from

recording it. If the cover is anything to go by then editorial knew full well that only the backup story could hold up (a bit), whereas the main feature simply makes you want to never ever pick up a copy of Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen again. The story behind this title, however, is a highly interesting piece of comic book history. Jimmy Olsen, an important figure in the Superman mythos, actually made his debut not in a comic but the Superman radio show in 1940 before appearing for the first time in Superman #13 (November-December 1941). In September 1954 he got his own title, Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen, which ran for a total of 163 issues up until March 1974. In key with the period, the series initially revolved around its protagonist undergoing all kinds of transformations, including Elastic Lad and Giant Turtle Man. Not surprisingly, by the time Jack Kirby came to DC from Marvel in early 1971, Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen was the lowest selling DC title of all - so Kirby picked it because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job (Wallace & Dolan, 2010). Using Jimmy Olsen as something akin to a launch pad, many of Kirby's Fourth World concepts (including the central villain Darkseid) first appeared here with the hope of giving his new creations and titles greater exposure to potential buyers. It was also, however, one of the first instances where "the King" had to acknowledge the limitations which DC would put on his (promised) artistic freedom as all of the Superman and Jimmy Olsen faces were being redrawn by Al Plastino and later by Murphy Anderson:

This evidently all happened before Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #157. When that issue was fresh off the press, Kirby had been off the book for almost a year, having left the series with issue #148 in April 1972. DC then tried to get Jimmy Olsen back on track, because

That's the explanation for the blurb "THE NEW" on the cover logo. Judging from the letters page, most readers wanted Jimmy Olsen to move away from the pre-Kirby "gets himself in trouble, is saved by Superman" mould, which Dorfman and Bates did seem to consciously avoid whilst moving the stories back from Kirby's extravagant plots back to the more conventional (some would say lame) DC style. But it didn't work, and in only one year's time Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen #164 (April-May 1974) would be merged with Superman's Girl Friend, Lois Lane (launched in 1958) to form a new title, Superman Family (which continued the numbering from Superman's Pal Jimmy Olsen). In that title, Olsen would finally become a more serious character who battled criminals as an urban investigative reporter known as "Mr Action" in crime stories which would rarely feature Superman. |

|||||

| BIBLIOGRAPHY PARKER John (2011) "Comics we love: 'Kamandi, the last boy on Earth'", published online at Comics Alliance SCHWARTZ Julius & Brian M. Thomsen (2000) Man of Two Worlds, Harper STUMP Greg (1996) “Infantino Raises Questions About CBG Letters Policy Following Kirby Controversy Flare-Up”, in The Comics Journal #191 (November 1996) WALLACE Daniel & Hannah Dolan (eds) (2010) DC Comics Year By Year A Visual Chronicle, Dorling Kindersley |

|||||

First

posted 24 January 2014 |

|||||