| BIBLIOGRAPHY BAKER Stacey,

MOTLEY Carol M. & HENDERSON Geraldine R. (2004) From

despicable to collectible: The Evolution of collective

memories for and the value of black advertising

memorabilia, published in Journal of Advertising

Volume 33, Number 3 (Fall 2004)

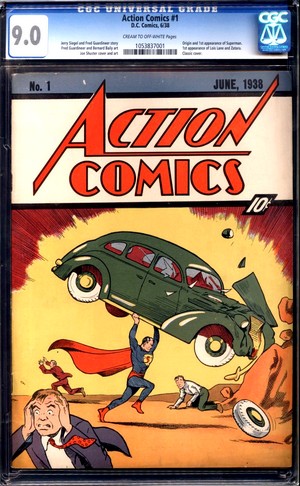

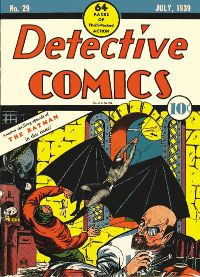

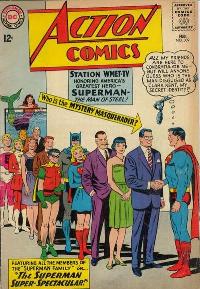

BBC NEWS

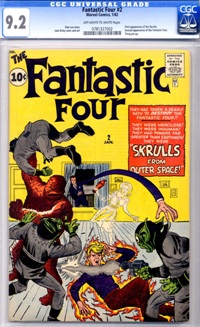

ONLINE (2011) "Action

Comics Superman debut copy sells for $2.16m", 1

December 2011

BBC NEWS

ONLINE (2013) "Fangio's

rare F1 Mercedes sells for £17.5m", 12 July

2013

BISCHOFF Dan

(2008) "Art auctions reflect economic

collapse",

The Star-Ledger, 29 November 29 2008

BRADY Terence

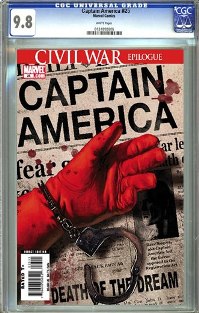

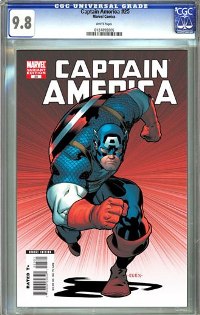

J. (2001) CGC: "The good, the bad & the ugly", published in Comics

Buyer's Guide #1464

CALLAHAN Timothy

(2009) Review of Amazing Spider-Man #583,

www.comicbookresources.com

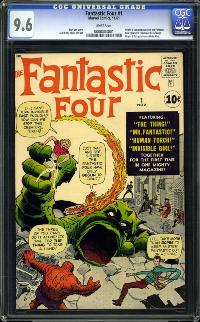

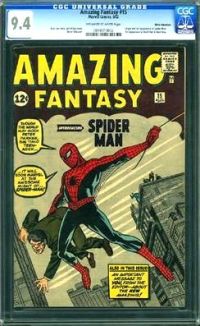

CGCCOMICS.COM (2004)

Comiclink.com sets record price for CGC certified 9.4

Amazing Fantasy #15, CGC eNewsletter Vol. 3 No. 2

CGCCOMICS.COM (----),

accessed 23 November 2007

COLTON

David (2009) "Spider-Man and Obama are both heroes

in new special-edition comic", Chicago Sun-Times,

8 January 2009

COMICPRICEINDEX.COM

(----), www.comicpriceindex.com, accessed 6

December 2007

COMICS PRICE GUIDE NEWS

(2009) Record

breaking $3,7 million weekend at Heritage Comics Auction,

28 May 2009

CREWS

Barbara (2007) "Rare comic prices from

ebay", about.com Collectibles Guide

DOUGHERTY

Conor (2005) "Bang! Pow! Cash!", The

Wall Street Journal, 23 September 2005

DOWNES

John, Jordan Elliot & Sharon Goodman (2003) Barron's

Finance & Investment Handbook, 6th edition,

Hauppauge NY

EDWARS

Bruce (2007) "The Argosy Comic Book Price

Guide", www.quasarcomics.com

FLOOD Alison (2021) "First edition of Frankenstein

sells for record breaking $1.17m", The Guardian,

20 September 2021

GAMMILL

Martha (2009) "As the Economy Goes, So Goes the

Coin Market",

Gammill Coin Gazette, 18 July 2009

GELBER

Steven M. (1999) Hobbies - Leisure and the

culture of work in America, Columbia University

Press

HERITAGE

AUCTIONS (----) "What constitutes valuable?"

comics.ha.com (accessed 11 August 2009)

HIBBS

Brian (2001) "Ethics and the comics

industry", The Comics Buyers Guide

LEVITZ

Jennifer (2008) "When Stocks Tank, Some

Investors Stampede to Alpacas and Turn to Drink", Wall

Street Journal, 3 October 2008

LEWIS

Al (2013) 10

reasons comic books are the best investment,

published online 13 August 2013 at marketwatch.com

(accessed 20 April 2014)

LINGEN

Roy (----) "The stamp market - a trader's

view", lingens.com

LONG

Mary M. & SCHIFFMAN Leon G. (1997) Swatch

Fever: An allegory for understanding the paradox of

collecting, published in Psychology &

Marketing Vol. 14(5) (August 1997)

MARCOTTE

John (2005) "The comic-book apocalypse", badmouth.net

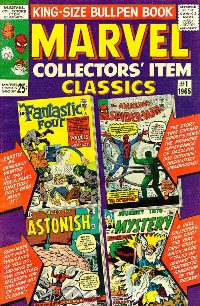

MARVEL

Comics (1973) April 1974 Bullpen Bulletin

MEEKS

Robert (2009) Comic collector may earn up to

$500,000 in auction, Associated Press Release

N.

N. (1994) "Comics Publishers Suffer Tough

Summer: Body Count Rises in Market Shakedown", The

Comics Journal #172 (November 1994 issue)

N.

N. (2003) "The semi-secret origins of the

Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide", scoop.diamondgalleries.com

N.

N. (2004) "Comiclink.com sets record price

for CGC certified 9.4 Amazing Fantasy #15", CGC

eNewsletter Vol. 3 No. 2

N.

N. (2007) "Amazing Fantasy #15 CGC 9.4

sells for $210,000", comicshares.com

N.

N. (2007b) "Art or Asset?", Wealth,

Northern Trust

N.

N. (2008) "ComicConnect Auction Posts

Record Sales Against 777 Point Dow Jones Drop", hakes.com

N.

N. (2009) "Amazing Fantasy #15 CGC 9.2

Sells for $190,000 at Pedigree Comics",

scoop.diamondgalleries.com

N.

N. (2009b) '"Obama' comic on top again", ICv2.com (17

March 2009)

N.N.

(2009c) "post by user

"jamstigator"" on www.kitcomm.com

[no longer accessible]

OVERSTREET

Robert M. (1976) The Overstreet Comic Book

Price Guide #6, Harmony Books

OVERSTREET

Robert M. (1982) The Overstreet Comic Book

Price Guide #12, Gemstone Publishing

OVERSTREET

Robert M. (1987) The Overstreet Comic Book

Price Guide #17, Gemstone Publishing

OVERSTREET

Robert M. (2006) The Overstreet Comic Book

Price Guide #36, Gemstone Publishing

REIER

Sharon (2007) "Collectibles march to the

baby boomer's tune", published in The

International Herald Tribune, 18 May 2007 issue

ROY

Rex (2009) "Sparkling Chrome, Beer Budget", New York Times

(21 May 2009)

SPITZNAGEL

Eric (2013) "Those

Comics in Your Basement? Probably Worthless", Bloomberg

Businessweek (30 October 2013)

THOMPSON

Michael (1979) Rubbish Theory: The Creation

and Destruction of Value, Oxford University Press

VOGEL

Carol (2009) "Picassos sell at Christie's

auction, after faltering at Sotheby's", New York Times

(7 May 2009)

WILSON

Mark (2007) "What is so great about a 9.4

book?", www.pgcmint.com

|