|

| |

|

|

STORING

COMIC BOOKS -

KEEP

CALM AND KNOW THY ENEMY

|

|

|

|

| |

| A 6th century BC Chinese

general, Sun Tzu authored an immensely influential book

on military strategy which today is best known in the

West as Sun Wu, the "Art of War".

Possibly one of the best known maximes put forward by Sun

Tzu is often quoted as "know your enemy". Not

taking into account the many philosophical undertones the

actual passage contains, it has become a nifty way of

saying: if you do something, be aware of why you are

doing it and what for. This is, of course, just as true when

it comes to storing comic books, where there is a current

mainstream consensus that "bagging and

boarding" a comic book is the way to go for safe

storage. But what exactly is everybody protecting their

comic book against? Do they know their collection's true

enemy?

|

| |

| In the

1970s, the average comic book reader would probably keep

his comics stacked in a simple pile somewhere. Although

still seen today, the average comic book reader is now

also an accidental comic book collector who handles and

stores his individual comics with at least a certain

amount of care. |

| |

| The "traditional"

loose stack has many disadvantages, the most

obvious being that because the spine side of a

comic book is thicker (accentuated by the two

staples used to hold the comic book together)

this can create a lopsided "U" which

will eventually roll the individual comics into

the very same shape (hence the term "spine

rolling"). The change of attitude in the

average comic-book-reader-turned-collector has

become so pronounced that it has in fact more or

less completely altered the traditional view of

comic books. Originally seen as a prime example

of ephemera (transitory printed matter

which, as the Greek noun describes, lasts no more

than a day and is not intended to be retained or

preserved) just the same as newspapers (a

parallel underscored by the use of the cheapest

grade of paper for both), comic books are now

understood to be items worth storing with care,

i.e. collectibles, rather than a disposable

commodity.

For

many, the question therefore is not whether

or not to think about storing comic books or

not, but rather how to store them. This

is mainly because virtually all published

information on storing comic books kicks off with

the bad news that any pre-1990s comic book is in

a process of deterioration since the

moment it went into circulation, due to the

acidity of the low-grade paper (known as newsprint)

used to print comic books prior to the early

1990s.

|

|

|

|

| |

| If the situation truly is

as bad as many expert collectors tell their audience,

then surely knowing exactly what kind of dangers comic

books face is imperative. |

| |

COMIC BOOK ENEMY NUMBER ONE:

PHYSICAL DAMAGE

|

| |

| The main

threat to comic books still is what it always used to be:

raw physical damage. Paper is a vulnerable material which

provides very little resistance and is thus easily

deformed or even torn, and the covers and interior pages

of a comic book will soon suffer if they are exposed to

excessive and/or careless handling. Unlike damage which

is triggered by chemical processes, physical damage is

usually instant, and the major element making comic books

so prone to physical damage is their relative

instability: they are usually thin (which offers little

or no resistance to disformation) and held together only

by two staples.

|

| |

|

|

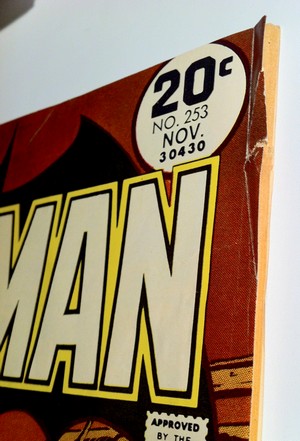

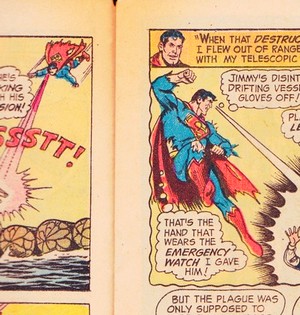

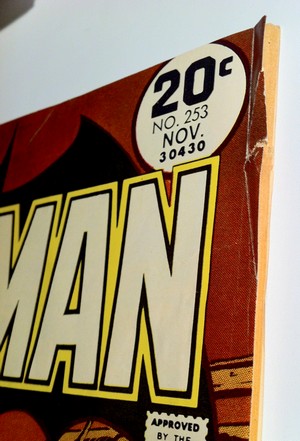

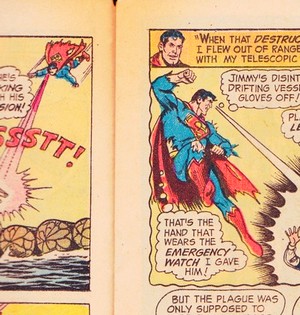

The copy of Batman

#253 illustrated here has suffered from such

purely physical damage: the corner of the cover

has been both creased and bent and then torn and

ripped through handling - a commonly known defect

in comic books and a typical sign of a certain

age (and therefore extended tear and wear). This kind of

very direct physical damage is most often also

inflicted by direct handling of a comic book.

Another important source of physical damage is

humidity - whilst sometimes less apparent, it is

nonetheless just as permanent as a nick or a

tear.

|

|

| |

| Whilst the

circled areas numbered "1" of this page from Batman

#253 show the already mentioned physical damage afflicted

by careless handling (scuffed and ragged edges and bent

corners), the circles numbered "2" show the

damage done by humidity. In this specific case, the paper

has started to curl slightly and displays the

"wave" which typically occurs when paper comes

into contact with e.g. water (right hand circle) whilst

also displaying the stains (left hand circle) which

remain when the paper has dried again. Although contrary to

the effects of direct physical impact the damage

inflicted by excess humidity can to acertain degree be

reversed (as per the emergency drying procedure suggested

by the Library of Congress), the fragility of

comic books (especially pre-1990) and the high absorbency

rate of the paper used in their printing usually results

in substantial damage - which can turn into a complete

loss if exposure to humidity is high and prolongued as

this will turn a comic book into a breeding ground for

mould.

It is fairly

obvious that in order to minimise the risk of direct

physical damage, individual comic books need to be

strengthened in terms of material stability and protected

from physical impact. The now standard method of storing

each comic individually in a protective see-through

sleeve into which a cardboard backing board is inserted

makes sense: it adds rigidity to the comic book and

protects it from all but the most massive bending forces.

As far as damage through humidity as well as soiling

goes, the sleeve (mostly made from polyethylene and

polypropylene) acts as a barrier, which when combined

with sensible storage (i.e. avoiding spaces which are

damp or prone to flooding) keeps dirt and humidity at

bay.

|

| |

| However, there is one form of

direct physical damage which protective sleeves

can only slow down at best but not prevent: the

attack by animals. Admittedly a far less frequent

source than tear and wear or humidity, insects

can do a surprising amount of damage - although

this is nothing compared to what rodents can do

to a comic book (or, as a matter of fact, any

paper product). The example shown here

illustrates the rather peculiar and therefore

easily identifiable damage rodents inflict (also

known as mouse or rat "chew")- they

literally take a bite out of your comic book, as

the tooth markings on the spine and the

indentations on the back cover of this copy of Superman's

Pal Jimmy Olsen #161 clearly show.

Incidentally, this comic book came from a sealed comic pack, showing

that plastic is neither a deterent nor a barrier.

As the copy of Batman #253 used as

illustration above was packaged together with Superman's

Pal Jimmy Olsen #161, the humidity damage

seen on the Batman issue could also be linked to

the rodents - not a very nice possibility, which

also illustrates that direct and indirect

physical damage can degrade a comic book to the

point where it once again turns into a piece of ephemera

- i.e. something which is best thrown away.

|

|

|

|

| |

| An aspect not mentioned too

often is the odour some comic books have taken on over

the years. If stored in a smoking household, an otherwise

(i.e. visually) well preserved comic book may have

acquired a smell which is both unpleasant - and permanent

in most cases. Again, plastic sleeves can act as

barriers, but only to a certain point, as they will never

be airtight. It is also interesting to note that there

are several reports on the web that comics can be highly

odorous even from inside a CGC slab casing. |

| |

COMIC BOOK ENEMY NUMBER TWO:

LIGHT

|

| |

| The most widely discussed

storage problem associated with comic books is the

degradation of paper linked to its inherent acidity.

However, this comic book enemy is not only often portrayed in

wildly exaggerated ways, but also describing and taking

the effects to be the cause - a classic case of mistaking

the enemy. It is now common knowledge that the

paper used for printing comics was (up until the

mid-1990s) of inferior quality; generally known and

refered to as newsprint, it was used primarily

for its low cost factor and its high absorbency, which

was well suited to rubber plates used on high-speed

offset presses.

|

| |

|

|

The drawback of the

production process of newsprint paper is

the fact that it results in very short

fibres and high levels of lignin (which is a natural bonding

element in plants that holds the wood

fiber together but gives off acids as it

deteriorates). This

combination triggers rapid discolouring

and oxidising (the paper turns brown),

and also sets free acids which degrade

the paper material even further - also a

major concern for many books printed

since 1850 (and most definitely so for

mass market paperbacks from the 1970s). However,

the acidity (although built-in to the

comic book) is only the catalyst, i.e. it

requires a triggering agent to do its

damage, which will then either result in acid-catalysed

hydrolysis or oxidation.

|

|

|

| |

| Acid hydrolysis breaks the

molecule chains and weakens the fibres, causing paper to

become hard and brittle. Of far greater concern to comic

book collectors (and hence the storage of their

collectibles) however is acid oxidation which discolours

the paper and makes it take on a yellow or even brownish

colour. Both the cellulose (and its derivatives) and the

lignin contained within the paper can be oxidised, but it

is the lignin that is the main cause of photo-yellowing

of paper (Seery, 2013). |

| |

| Lignin

has a chemical setup (specific chromophores and

carbonyl groups) which absorbs light in the near

ultraviolet (UV) spectrum of light. When this

happens, these chromophores decompose into

yellow-coloured ketones and quinones, i.e. they

turn the paper yellow. However, since these

yellow-coloured molecules themselves absorb

visible light, they also act as secondary

chromophores and can react even further, adding

to the yellowing and degradation processes

(Seery, 2013). This

makes it clear that the presence of light is more

important than the presence of lignin and other

acidic elements in terms of paper degradation -

which occurs because light is radiant energy that

causes irreversible change through its output of

chemical energy and the resulting photochemical

reaction.

The most potent

source of this destructive energy comes from just

beyond the limits of the visible spectrum of

light, as ultraviolet rays (with their shorter

wavelength and thus higher energy rate) are

especially harmful and a significant catalyst for

photochemical destruction.

The problem is that

UV light is not only present in all daylight (and

most abundantly in direct sunlight) but also in

many fluorescent and metal halogen lamps.

|

|

(scienceinschool.org)

|

|

| |

| There is some overlap in

the forms of deterioration caused by visible light and

UV, but as a generalization exposure to visible light

causes fading and bleaching of colours in paper, whilst

UV causes the yellowing (Vávrová, Kotlík, Durovic

& Brezová, 2011) - the different types of damage

typically caused are the result of the different photon

energies of UV and visible light (Michalski, 2013). |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Fading

mostly occurs on comic book

covers when stored in conditions

which subject them to direct (and

often prolongued) exposure to

sunlight (as illustrated above). If the comics

were stacked, this can result in

the typical fading patterns found

when only a certain part of the

cover was exposed whilst the rest

was covered by the comic book

lying on top.

Browning

will always occur predominantly

on surfaces which are highly

exposed to light, i.e. the edges.

This is where the oxidation

process is initiated, but with

subsequent "bleeding"

into interior areas once the

photochemical processes take

place. This often runs along the

spine but can ultimately befall

the entire page(s).

A

chemical catalyst which can be

the result of handling is lactic

acid. As a component of human

sweat, this can be transferred to

paper surfaces during handling.

and although a weak acid this can

contribute to the deteriation.

|

|

|

|

| |

COMIC BOOK

STORAGE AND PROTECTION:

KEEP CALM

|

|

| |

| Having identified the two

main enemies which comic books are up against if simply

left lying about, it is now time to think about adequate

measures to fight those enemies. It is also, however, a

good and sound advice to stay calm about this. Why? Because having undergone the

magic transformation from disposables to collectibles,

comic books have also become the focus of attention of

the collectibles market - a highly constructed

environment which is as much about a hobby as it is about

making money (cf. THOUGHT BALLOON #34). One of the most important elements

which operates any collectibles market is the condition

of an object (usually referred to as "grade")

in conjunction with scarcity. In other words: collectors

will usually prefer items in excellent condition to items

of a lesser grade, and the fewer well-preserved objects

available the higher the price which a collector can be

expected to pay for it.

Combined with the fact that

the world wide web is a marketplace as much as it is an

information hub, this explains why so much information to

be found on the internet today on comic book storage

is actually, to all intent and purpose, concerned with

long term comic book conservation. The

difference may appear subtle at first sight, but in

reality the two concepts are fundamentally different.

Whereas storing comic books is an attempt to prevent

major damage and degradation and thus preserve them in

the best shape possible (i.e. accepting a few minor

tell-tale signs of its actual age), conservation is aimed

at preserving a comic book in its current material state,

or in other words "freezing" the current

condition for posterity.

In practical life, this

difference draws the line between a collector and an

archival museum - unless, that is, conservation is seen

as a means of safeguarding and possibly raising a

collectible's monetary value for future sales

(ultimately, this approach to conservation may even bleed

into restoration of comic books, which if used

in conjunction with the intention to sell is frowned upon

by most).

The speculative nature of

the collectible's market has thus permeated information

on storage and maintenance of comic books to the point

where the differing priorities of collectors and

speculators often become blurred and confused. The

resulting advice given to "all collectors" is

more often than not over the top, simply because most

collectors with no speculative investment interest will

accept some minor degradation occuring after 30+ years,

whereas a perfect grade conservation guarantee up to the

year 2100 only makes sense if later generations are taken

into account. However, even the idea of leaving behind a

profitable inheritance - again planted by the forces

which drive the speculative collectibles market - is made

questionable by the simple fact that almost any comic

book published since 1990 will be in excellent supply

both in terms of numbers and grade for decades to come

(cf. THOUGHT BALLOON #34).

Sometimes the advice found

on comic book storage makes it seem as though a large

percentage of comic book collections worldwide is just

about to turn into brown crumbles and heaps of dust. Keep

calm - that isn't so.

|

| |

COMIC BOOK

STORAGE AND PROTECTION:

BAGS AND BOARDS

|

|

| |

| As

mentioned, minimising the risk of physical damage to

comic books is easy - by simply strengthening individual

issues by inserting them in a protective sleeve into

which a cardboard backing board is inserted: a well

established best practice commonly known as "bagging

and boarding". |

| |

|

|

The variety of products

offered and on sale is enormous, but the most

commonly used materials are polyethylene and

polypropylene. Both of these materials are

manufactured with solvents and additives which

break down over time, causing some experts to

point out that only uncoated polyester film

(known as Mylar[R]) will remain

stable - however, all three of the mentioned

materials have accepted photo activity test

ratings which make them safe for long-term

storage (Teygeler 2004). Polyvinylchloride (PVC)

however should be avoided, as it can break down

into hydrochloric acid over time. All types of plastic bags

have their own inherent problems: they can trap

moisture (which may lead to mold growth), their

static electricity can lift fragile, flaking

surfaces, and plastic doesn’t provide any

buffering protection against changes in humidity

like paper can.

|

|

| |

| This

latter aspect is another point in favour of

backboards in general and acid-free backboards in

specific, as nobody will want to add to the

inherent acidity in the paper. However,

"acid-free" signifies "at the time

of manufacture"; any pronounced level of

acidity in a comic book will eventually

"bleed" into the backboard. Possibly the

most effective method of maintaining a comic book

collection therefore are regular checks, which

ultimately are more important than chosing the

best archival-safe materials. Looking through the

collection on a regular basis will reveal any

possible problem in its beginning stages, before

substantial damage has occured.

The

real question now is - hardly ever raised in

conjunction with the advice to bag and board

comic books - whether or not it is sensible to

apply this storage measure to all comic

books in a collection.

Obviously,

comic books which are known or believed or hoped

to be worth a lot of money now or any time in the

future should be carefully bagged and boarded -

and then stored in a bank vault.

Sentimental

importance and nostalgia is a valid criteria for

any collector to store certain items with special

care. For these comic books, bagging and boarding

may make sense.

For

the remainder of a comic collection it is at

least worth pointing out that not

boarding and bagging a comic book does not

automatically make it doomed - especially

post-1995 comic books, which are either printed

on acid free paper (in line with a 1989

commitment by major US print publishers to

utilizing ISO 9706 certified permanent durable

paper) or on high quality glossy paper which has

been chemically de-pulped and coated with an

alkaline buffer to better protect against

environmental pollutants that cause acid

hydrolysis (Teygeler 2004). Generally speaking,

better paper quality goes hand in hand with a

more sturdy product which is less prone to tear

and wear, although there can be huge differences.

The current single issues from Marvel are at

times printed on paper so thin that they can be

even flimsier than Bronze Age examples, whereas

DC has even started to use thicker grade paper

(almost cardboard) for their covers in 2014.

Archie Comics and Boom Studio have a similiar

setup, and Dynamite uses fairly heavy paper stock

throughout.

Bagging and boarding

each and every comic book in a collection is not

only a cost factor, it also adds two new

collections to the comic books: one is plastic

bags, the other backing boards - and both take up

space.

|

| |

|

COMIC BOOK

STORAGE AND PROTECTION:

LIGHTS OUT

|

|

| |

| Polybags

and backboards will protect comic books against physical

damage, but not against chemical degradation. The most

important element to shy away from, as mentioned before,

is light. |

| |

| This makes it a logical

conclusion that comic books should be stored in a

dark place. The traditional storing

method addressing this need is the "long

box" or the "short box", a

standard strong cardboard box which holds comic

books in an upright position. Using these boxes,

comic books can be stored in the dark, which

counteracts the main degradation source. Again,

acid-free cardboard boxes are available from

specialist sources.

Container

devices used to store individual comic books in

one place should not only provide an environment

which is protective of light, they should also

have a certain stability and be able to withstand

a few undeliberate knocks. Although the stability

of long or short boxes is probably underestimated

by many, cardboard does have its limitations over

time, especially when several boxes need to be

stacked. Outward appearance, although completely

irrelevant with regard to storage quality, also

plays a part in many collectors looking for and

turning to other solutions with more durable

materials.

|

|

A typical example of a comic

books short box (in this case from the Miller

Hobby brand of comic book storage

boxes)

[image is (c) Miller Hobby,

used with kind permission]

|

|

| |

| It should be mentioned that

exposure to light continues to have a degradation effect

to a certain degree even during subsequent dark storage -

a phenomenon known as post-irradiation effect (Vávrová,

Kotlík, Durovic & Brezová, 2011). This also

illustrates a fundamental dilemma: light is the main

source of degradation to comic books, yet it is required

to read and enjoy them. UV filters could be an option,

although hardly worth the effort for most items in an

average collection. In

addition to dark storage, the American Institute for Conservation

of Historic & Artistic Works advises to keep paper objects in a

cool and dry environment, ideally maintaining a

temperature below 72 degrees Fahrenheit at a relative

humidity of between 30 percent and 50 percent. Climatic

fluctuations cause papers to expand and contract, and

warm or moist conditions should be avoided, for the

reasons given above.

Bagged and boarded comic

books are generally stored in an upright position. There is, however,

ample and informed information available which dispells

the myth of the absolute imperative for vertical storage.

The Northeast Document Conservation Center (a non-profit

regional conservation center in the United States,

founded in 1973 and counting amongst its clients the

Boston Public Library and Harvard University) advised

that although vertical storage in office files or in

upright flip-top archival document storage boxes is

acceptable for legal-sized or smaller documents, any

objects larger than 15" x 9" should be stored

flat. This is due to the pull forces which documents

stored in an upright position are subject to, and it is

safe to assume that what is best practice for larger size

documents works out well for comic books as well.

|

| |

CONCLUSION:

KNOW THY ENEMY, KEEP

CALM & DO IT YOUR WAY

|

|

| |

| There

obviously are huge differences between individual

comic book collectors, and these differences

spill over into just what kind of comic book

collections these individuals call their own,

both in terms of numbers and age of the

individual comic books. The approaches to storage

may therefore also differ, for reasons easily

understood. One thing, however, remains a

constant: the maintenance of any collection

should be done sensibly. Counteracting, for

example, the use of acid-free backboards with the

use of acidic storage boxes not only defies the

logic but the actual goal of the exercise. It may

also be that not all individual comics from a

collection merit elaborate storage, and regrets

twenty, thirty years from now for having picked

the wrong titles for "basic" storage

(when all of a sudden the sentimental value of Zapman

issues outweigh those of the Batman

comics, even though it was completely the other

way round at the time) should not be too harsh as

any comic book stored subject to a small set of

best practice rules should remain in more than

just acceptable condition. The following

advice from the Shiloh Museum concerns

photographs, but poses questions just as valid

for comic books:

"Storing photos

properly is expensive and time consuming.

Before you start, determine if all of your

photos are worth the effort. Ask yourself:

which photos should be considered heirlooms?

which are poor quality or redundant? which

are the most fragile?"

It really is quite basic -

individual comic books should be stored in a

cool, dry and - most importantly - dark

environment. Everything else, such as protection

from soiling, protection from "acid

leaking" from other material containing wood

pulp, protection from other pollutants or

protection from soiling or insects is really up

to the individual collector and his individual

storage situation and needs.

|

|

| |

| |

| References MICHALSKI

Stefan (2013) Agent of Deterioration: Light,

Ultraviolet and Infrared, Canadian

Conservation Institute

SEERY

Michael (2013) "Savin paper", in Education

in Chemistry, March 2013, 23-25

TEYGELER

R. (2004). Preserving paper: Recent advances, in

J. Feather (Ed) Managing preservation for

libraries and archives: Current practice and

future development, Ashgate Publishing

VAVROVA

Petra, Petr Kotlík, Michal Durovic & Vlasta

Brezová (2011) "Damage to Paper Due to

Visible Light Irradiation and Post-Radiation

Effects after Two Years of Storage in

Darkness", in New Approaches to Book and

Paper Conservation-Restoration, Patricia

Engel et al. (eds), Verlag Berger

|

|

| |

First

published on the web 9 March 2010

Completely revised and updated 19 July 2014

|

| |

Content is (c) 2010-2014 A. T. Wymann

|