|

|

Eugene

"Gene" Colan (nicknamed both "Gentleman"

and "the Dean" at

Marvel by Stan Lee) was born on 1

September 1926 in the Bronx, New York

City, and passed away on 23 June 2011 in

New York City. He

had grown up and received his education

in the Big Apple and graduated from

George Washington High School in

Washington Heights (Manhattan) before

going on to study at the Art Students

League of New York under renowned

illustrator Frank Riley and the famous

surrealistic, modern Japanese painter

Kuniashi (genecolan.com).

"My

mother owned an antique business.

(...) My father was in the insurance

business. I was into art, very early

on. I started at about three, and I

drew everything in sight (...) That

was my passion, and I didn't care

about anything else, not really (...)

I had my pencil and pad, and I was

set." (Irving, 2010)

|

|

|

| |

During World War II, a two

year ticket with Special Services in the Army Air

Corps found Corporal Colan in the Philippines

where his artwork brightened the pages of the Manila

Times and won him numerous awards.

"I

wanted to have something to do with film

making when I was very young, but I didn't

think I'd really make it in that. (...) Being

a very sensitive person, I wouldn't be able

to handle what Hollywood dishes out. (...) I

chose going into comic books because it's

storytelling, and not just drawing, but

telling good stories. (...) Milton Caniff was

my biggest influence, and the artist who

inspired me the most. There may have been

better artists than he, but he had a way with

shadows and blacks when he did "Terry

and the Pirates" that I loved so

much." (Irving,

2010)

Back

in the US, Gene Colan's official career in comics

began in 1944 at Fiction House, where he saw his

first work - a one-page filler illustration of a

P-51B Mustang - published in Wings Comics

#52 (December 1944), whilst his first work on an

actual comics story - a seven-page "Clipper

Kirk" feature - was published in the

following month's issue (genecolan.com / Best,

2003).

|

|

|

|

| |

In 1946,

Gene decided to go for a permanent job in the comic

industry and submitted his work to both National (DC) and

Timely (Marvel) Comics.

"I

was living with my parents. I worked very hard on a

war story, about seven or eight pages long, and I did

all the lettering myself, I inked it myself, I even

had a wash effect over it. I did everything I could

do, and I brought it over to Timely (...) and [Al

Sulman] came out and met me in the waiting room,

looked at my work, and said 'Sit here for a minute'.

And he brought the work in, and disappeared for about

10 minutes or so... then came back out and said 'Come

with me'. That's how I met Stan [Lee]. Just like

that, and I had a job." (Thomas, 2000)

In the end,

Stan Lee was impressed enough to hire Gene for around

sixty odd dollars a week (genecolan.com).

"When

I first started with Timely (...) we were working in

the Empire State Building and that’s where I

really got the experience that I needed. I was

hired to do the work and I was paid for it and I

didn’t know a heck of a lot about anything and

of course there was an art director there, his name

was Syd Shores and he showed me everything.(...) he

was just great. Captain America, Two Gun Kid,

Kid Colt, westerns, and horses - he could do

anything, and he helped me a lot. He brushed up

all the bad stuff that I was doing." (Best,

2003)

But only two

years later, Timely decided to use up a large inventory

of accumulated unpublished artwork - with both obvious

and tough results for the artists.

|

| |

Battlefield

#5

(November 1952)

|

|

"The

bottom dropped out and we had to take

what we could get. (...) It happened

at a time [in 1948] when everybody in

the art department was let go. (...)

People would have to fend for

themselves, getting freelance or

whatever. (...) I decided to take the

day off and decided to see what I

could get. I came back with some good

accounts: Quality Comics was one, and

I worked for Ziff-Davis, and maybe

one or two others." (Irving,

2010)

Also in 1948 Colan

became a freelance artist for National

(DC). Always striving for complete

accuracy, Gene Colan meticulously

researched his countless war stories for

DC such as All-American Men at War

and Our Army at War, as well as

Atlas Comics' Battle, Battlefront,

G.I. Tales, Marines in Battle

and Navy Tales (to name only a

few). His earliest confirmed credit

during this time is pencilling and inking

the six-page crime fiction story

"Dream Of Doom" in Lawbreakers

Always Lose #6 (Atlas, February

1949).

Following the Wertham

scare of 1954 and the downturn the

industry faced Gene Colan left comic

books for good for a number of years

before returning to the medium in 1962.

Initally working for DC and Dell, he also

began to do some occasional work for

Marvel as of 1963 with mystery backups on

Journey into Mystery and Western

stories.

|

|

|

| |

| In 1965 Colan did his first

superhero work on Sub-Mariner and Iron Man under

the pseudonym of Alan Austin (as he was still

primarily working for DC), a modus operandi

which was quickly dropped as his style was so

unique that the authorship of the artwork was too

evident to be hidden behind an alter ego. And again,

Gene Colan was looking to provide his artwork

with authenticity and accuracy.

"Authenticity,

for me, was important, because it made the

reader feel 'This is real This is not just a

comic book' (...) It gave the reader the

sense that he belonged in the story and

wasn't just reading something. I romanced it

in my head: I was into it and wanted the

reader to be into it." (Irving,

2010)

"I

would take stuff out of magazines,

newspapers, anything that I thought would be

useful. (...) Through the years

I’ve compiled such a collection of

pictures dealing with every conceivable

subject that I very seldom ever have to go

anywhere to get outside information because

being in the business fifty some odd years

you get quite a collection." (Best,

2003)

By

1966 Gene Colan was firmly established as the

artist of several ongoing Marvel series and

characters, and took on Daredevil which

would become his signatory title for many.

Other

Marvel titles which Gene Colan had lengthy runs

on and was applauded for included Iron Man,

Captain America and Doctor Strange

before he took on all 70 issues of Tomb of

Dracula as of 1972 - the series is

one of the seminal monuments to his artistic

expertise and craftmanship. He also made waves

with his pencils on Marvel's satirical Howard

the Duck, which kicked off in 1976.

Gene

Colan won the Shazam Award for Best Penciller

(Dramatic Division) in 1974, received the 1977

and 1979 Eagle Award, and was nominated for five

Eagle Awards in 1978.

However,

when Jim Shooter became editor-in-chief in 1978,

the fun times at Marvel were coming to an end for

Gene Colan.

"I

knew the trouble was heading my way with

Shooter. He overcorrected every single line I

drew on every single panel (...) he was about

tyranny just for the sake of it." (Irving,

2010)

Shooter's

own take on that period in time makes it quite

clear that even though they were working in the

same business the two men had completely opposite

views and understandings of their trade:

"I

said "You've gotta do better stuff. I'm

gonna make you redraw when you don't."

(...) That's when Wolfman had gone over to

DC, thinking fondly of the Dracula days, got

him to come over [to DC]. And that was better

for everybody I think." (M.

Thomas, 2000)

|

|

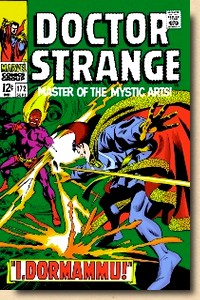

Doctor Strange #172

(September 1968)

Gene Colan's Picadilly Circus

sets the scene in Tomb of Dracula #25

(October 1974)

Gene Colan in 1977

|

|

| |

| After

splitting from Marvel for both creative and professional

reasons, Gene Colan thus found himself back once again at

DC Comics in 1982, where he reunited with Marv Wolfman

whom he had worked with so long and so successfully at

Marvel. |

| |

| DC was eager to promote this

dream team which now was part of their own ranks,

but their reunion project Night Force

(featuring a team of individuals fighting

supernatural threats) which billed Wolfman and

Colan as the "Masters of the

Macabre" only lasted for 14 issues

before cancellation.

This

was in spite of obvious attempts by the creative

team to somehow continue the legacy of Tomb

of Dracula - one of the main characters was

Vanessa van Helsing, granddaughter of Abraham van

Helsing, which would thus make her a sister of

Rachel van Helsing from Tomb of Dracula.

Gene

Colan was far more successful in bringing his

shadowy and moody visuals to Batman, one of whose

primary artists he became from 1982 to 1986 in

both Detective Comics and Batman,

even though his overall pencilling did become

somewhat lighter due to DC's very strict art

policy.

"Dick

Giordano gave [Batman] to me. I enjoyed

drawing Batman, but my experience working for

the company and the editor on the book left

something to be desired." (Klaehn,

2010)

"DC

was a tough outfit. They wanted an in-house

look for all of the artwork, and they wanted

the artists to draw somewhat the same." (Irving,

2010)

"DC

was way too controlling, and no artistic

freedom (...) Marvel was like working for

family, DC like working for the

principal." (Klaehn,

2010)

Nonetheless,

Gene Colan's visions of Batman matched up well

with the character's eesentials as shaped by

Denny O'Neil and Neal Adams:

"[Batman

is] a very mysterious figure of the night

(...) [a classic Batman story is] something

mystifying and unearthly, left to the reader

to figure out." (Klaehn,

2010)

When

Conway and Colan delved into a multi-issue story

arc in mid-1982 which had Batman fighting

vampires, it could have been perceived as a

typecast gridlock for Gentleman Gene. However,

the resulting epic story spread out across Batman

#349, Batman

#350, Detective

Comics #517, Batman

#351 and Detective

Comics #518 became an instant classic

which had readers in rapture.

At

DC Gene Colan also pencilled Wonder Woman

from 1982 to 1983, worked with Greg Potter on Jemm,

Son of Saturn (1984-85), with Cary Bates on Silverblade

(1987-88), and he pencilled the first six issues

of Doug Moench's 1987 revival of The Spectre.

Between

1981 and 1986 Colan also managed to break free

from the established comic book industry

production chain of penciller and inker by

creating finished drawings in graphite and

watercolor on projects such as the feature

"Ragamuffins" in Eclipse as well

as in the DC Comics noir miniseries Nathaniel

Dusk (1984) and Nathaniel Dusk II

(1985–86), all of which were written by Don

McGregor.

|

|

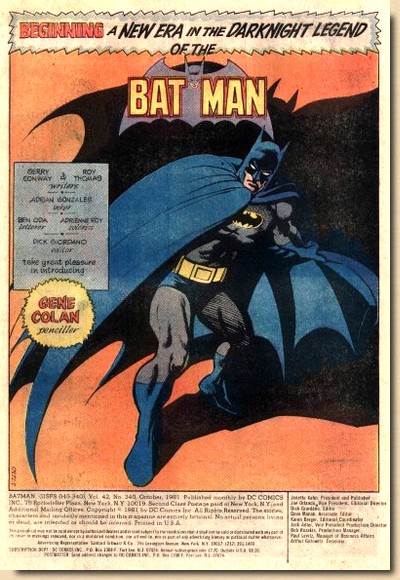

Gene Colan is formally

introduced to the readership on the splashpage of

Batman #340 (October 1981)

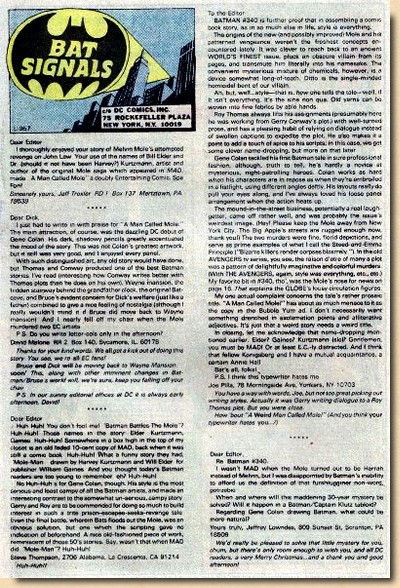

First and enthusiastic

readers' reactions to Gene Colan's appointment to

the Batman Universe on the letters page of Batman

#345 (March 1982)

|

|

| |

Gene Colan

also did a fair amount of work for independent

comic book publishers before returning to Marvel

in 1990 where he once again collaborated with

Marv Wolfman on a new The Tomb of Dracula

series and returned to Daredevil in

1997, the title for which he had produced some of

his most classic and best loved superhero artwork

for Marvel in the late Silver and early Bronze

Age.

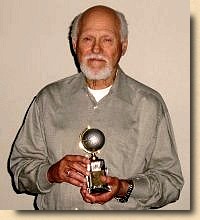

In 2005, Gene Colan was

inducted into the comics industry's Will Eisner

Comic Book Hall of Fame. In 2007, he pencilled the

final pages of Blade (vol. 3) #12

depicting a flashback in which Blade dresses in

his original outfit from the original 1970s

series, and that same year, he also drew 3 pages

(18-20) for the anniversary 100th issue of volume

two of Daredevil.

He continued to draw

occasional comics and covers throughout his

retirement, his last work being for Captain

America #601 (September 2009) for which he

won yet another Eisner Award, this time for Best

Single Issue (together with writer Ed Brubaker).

"I didn't have a

deadline. (...) It took me close to two

years." (Irving, 2010)

This award - together with

the Comic Art Professional Society's Sergio Award

which he recived in October 2009 - no doubt

marked a fitting end for a unique career of an

artist whose professionalism and dedication made

him a legend of the comic book industry and 20th century

popular culture in his own lifetime.

"You

know you can draw a fine picture, but unless

somebody sees it and appreciates it, it means

nothing. You’ve got to get somebody to

say to you “Gee that was a good picture

you drew” or that was a good story you

did, and you don’t get that very much in

this business, you don’t get those kind

of compliments all that much." (Best,

2003)

"Most

of the inspiration came from films and to me

the movie screen was just one gigantic comic

book panel." (Best,

2003)

"You

know comic book artists never sit down at a

convention table to discuss how they're gonna

do this and how they're gonna do that - it

was always over the phone, very quickly, or

in passing each other you'd spend a few

minutes talking about it, maybe fifteen or

so, and that would be it. It's all that was

required." (Siuntres,

2005)

"It’s

very hard to get a good inker to go

over. If you were a penciler and you

did fabulous pencil work, or what you thought

was pretty darn good and then you give it to

an inker, well then you’ve got your

style to begin with and then you’ve got

the inkers style on top of your style.

And you’ve got two styles representing

one piece of art. And I’ve always

had a problem getting a good inker." (Best,

2003)

When

Gene Colan passed away on 23 June 2011, the

American comic book industry lost a true giant of

a legend - one of the best and most prolific

artist and entertainer the medium ever had..

|

|

Gene Colan receiving his

Eisner Award in 2005

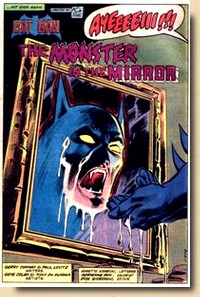

Detective

Comics #517

(August 1982)

Detective Comics #567

(October 1986)

|

|

| |

Stan

Lee: "Trying to describe Gene

Colan's incredible artwork is like trying to describe

a rainbow. The best way to appreciate it is to look

at it. (...) He could do romance, horror,

superheroes, whatever it was he could do it and he

did it with great style." (Comic Book

Profiles No. 6, Spring 1999)

Marv

Wolfman: "His graphic was

perfect, Gene is a brilliant artist." (Siuntres,

2006)

Jim

Lee: "His ability

to create dramatic, multi-valued tonal illustrations

using straight India ink and board was

unparalleled." (Boyle, 2011)

Kelly

Jones: "There's no comics

artist I can think of offhand who draws human facial

expressions as well as Gene and very few who are as

good as Gene at setting a mood." (Comic

Book Profiles No. 6, Spring 1999)

Steve

Gerber: "If I

was to say one thing about Gene Colan's work, it's

atmosphere and rhythm, because the lines are so

musical. They flow into one another, and you can hear

the snap of Dracula's cape. You can hear Daredevil

whizzing by you - it's terrific. Not too many artists

are capable of that." (Comic

Book Profiles No. 6, Spring 1999)

Tom

Spurgeon: "He was his own chapter

in the history of comics." (Moore &

Ilnytzky, 2011)

Gerry

Conway: "I had three favorite

artists that I worked with in my career and they

would be Ross Andru (...) Jose Garcia-Lopez (...) and

Gene Colan. Because we had two really good runs

together on Daredevil in the early 70's and on Batman

in the early 80's. Those are sort of the three

artists who I feel happiest in terms of long

relationships with (...) those were the guys I think

I did some of my best work with." (Daudt, n.a.)

|

| |

| But Gene

Colan was not only a master of his trade, he was also a

witty and sharp observer and analyst of 20th century

American comic book culture and its industry, of which he

had a lengthy and

seasoned first hand working knowledge. He made himself

available for many interviews, and thanks to Gene Colan's

willingness to put forward his thoughts - "I

always have something to say about the industry"

- many an information and insight on production methods

and publishing politics which otherwise would have been

lost in time is now on record for all who are interested

in comic books and their history. |

| |

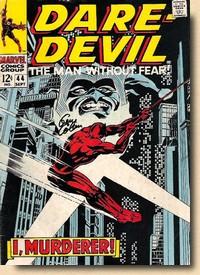

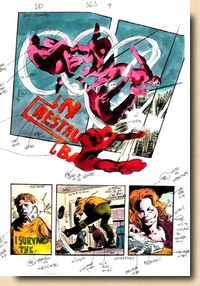

Daredevil

#44

(September 1968)

cover signed by Gene Colan

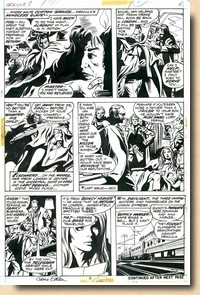

Tomb of Dracula

#7, pg 6

(March 1973)

original artwork by Gene Colan, expertly

inked by Tom Palmer

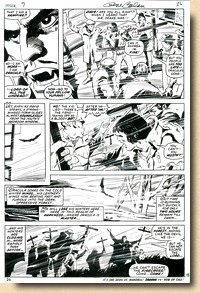

Tomb of Dracula

#9, pg 26

(June 1973)

original artwork by Gene Colan, inked by

Vince Colletta, notorious for his

tendency to "simplify"

pencilwork and leave out a lot of detail

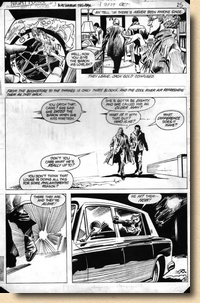

Night Force #3,

pg 20

(October 1982)

original artwork by Gene Colan, inked by

Bob Smith

Daredevil

#363

(April 1997)

colour guide by Christie Scheele on a

production stat of Gene Colan's artwork

|

|

"[Film]

was really a black and white medium

when I grew up. Most of the

films that were in the theatres were

all black and white, we didn’t

have very many Technicolor films then

so I was brought up in a world of

black and white. Aside from

that, that’s how I saw

everything anyway. I wasn’t into

color it never occurred to me to have

anything colored, so I drew it in

black and white and if they wanted to

add color to it then go ahead, but

that’s just how I saw

things. Most of the inspiration

came from films and to me the movie

screen was just one gigantic comic

book panel." (Best,

2003)

"[It

was] at the age of 5 when I was

exposed to my first horror film. It

was Frankenstein. My father wanted to

see it and he took me along. Boy, did

that traumatize me! That was in 1931.

From then on, I was intrigued with

horror. I didn’t realize it in

those years, but it kind of crept up

on me. I sort of took what I loved

from the screen and put it on paper

(...) Whatever scary movie was out,

I'd see it, and a combination of

things, but I always had an affinity

for that stuff (...) I just love

the atmosphere - you know, old

castles, cemeteries, fog - all that

stuff. I've always been interested in

that." (Siuntres, 2005)

"[Stan

Lee] would just give me - and any of

the other artists that could do it -

a brief thumbnail idea of what the

plot was - this is the beginning,

this is the middle, and that's the

end - and I wouldn't come into the

city with that, I would tape record

him telling me the story over the

phone. That way I could follow the

message that he left for me, on the

recorder, and space it out the way he

tells it. And I would say 'well this

will take just so many pages and this

should take so many' and I would

equal it out until I felt that it

would - in my mind, I didn't make

notes or anything - that it should

eat up about 18 pages, and tell the

story. And sometimes I would run into

trouble and other times I would be

right on the nailhead. I just

couldn't stand doing thumbnail

sketches of these things, I just

wanted to get right to it - and I

would start with panel one." (Siuntres,

2005)

"You

know comic book artists never sit

down at a convention table to discuss

how they're gonna do this and how

they're gonna do that - it was always

over the phone, very quickly, or in

passing each other you'd spend a few

minutes talking about it, maybe

fifteen or so, and that would be it.

It's all that was required." (Siuntres,

2005)

"An

artist, as a rule, is not aware of a

style; he just does it. You

know when you write your name you

don’t think about how

you’re writing it but yet it can

be spotted by everyone and

they’ll know that that’s

you. When you’ve written

your name out it has a style to it,

it’s very hard to copy and

artwork is the same thing – it

has a style to it and you just don't

sit down and try to develop a style

it just happens. An unconscious

experience." (Best,

2003)

"There

are no two artists that look at

things the same way. Everybody has

their method of creating a

mood. I have mine, they have

theirs. Every time I did a job

I was basically entertaining myself,

having a good time with it, and I

enjoyed that. And even though I

would put lines down that I knew the

inker wouldn’t even begin to

bother with, I’d put them in

anyway, because it made the final

picture I’d be doing

finished. I gave it all I

could. Whether they inked it or

not, that was something else

again. Once it left my hands I

didn’t even care who inked

it. There was no point in

arguing with trying to get a specific

inker to work on your stuff because

they didn’t listen to you.

If they needed to a particular job

done in a hurry and all the best

inkers were working on other things

they would give it to somebody

else."

(Best, 2003)

"I

worked real hard on my art, why

should somebody come over and wreck

it up? So, I never really had a good

inker, not until Tom [Palmer] came

along. (...) I liked Tom's work very

much. It was weighty, and he put in

all the stuff that I liked - kind of

like a Caniff. My work is not easy to

follow, and he must've had a helluva

time with it. Tom is an illustrator

himself; he's done a lot of

advertising art. So, he was very

well-suited to it." (Field, 2001)

"Fortunately

for me the last ten years or so

I’ve had a lot of my work

printed only in pencil." (Best,

2003)

"The

only strip I really begged for was

Dracula. [Stan Lee] promised it to

me, but then he changed his mind, he

was going to give it to Bill Everett

(...) But I didn't take that for an

answer. I worked up a page of

Dracula, long before Bill did

anything (...) and I sent it in. I

got an immediate call back. Stan

said, "The strip is

yours"." (Thomas, 2000)

"I

don’t remember when it started

but I guess it started in the

‘60’s when they began to

give back to the artists, after the

stories were printed, the original

artwork. But if an artist, if a

penciler had to share the story with

an inker then the inker would get a

small percentage of it and the

penciler got most of it. Out of

an 18-page story an inker might get

five or six pages and then the

penciler would get all the

rest. So unless I inked it

myself I never got the full amount of

pages back at anytime, I would get

most of them back, but not all of

them." (Best,

2003)

"I think

comic books have gotten out of hand

these days because they show

everything that films portray and

they don’t spare anything.

They don’t leave anything to the

imagination of the reader."

(Best, 2003)

"I never

thought my career would take on the

proportions that it has (...) I was

just proud of the fact that I could

actually draw something and do a

story. (...) So it took off and the

proportion that it reached just

boggles the mind. I'm very fortunate

in that respect." (Best,

2010)

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| BIBLOGRAPHY BEST

Daniel (2003) "Gene Colan Interview", www.adelaidecomicsandbooks.com

BEST

Daniel (2010) "Gene Colan Interview", www.ohdannyboy.blogspot.com

BOYLE

Christina (2011) "Gene Colan, comic book legend and

Bronx-born artist, dies at at 84", in New York

Daily News, 24 June 2011

DAUDT

Ron E. (N.A.) "Gerry Conway

Interview", www.wtv-zone.com

FIELD

Tom (2001) "The Colan Mystique, in Comic Book

Artist #13

IRVING

Christopher (2010) "Gene Colan: On

Vampires, Shadows, and the Industry", www.nycgraphicnovelists.com

KLAEHN

Jefferey (2010) "Gene Colan Interview", jefferyklaehn.blogspot.com

MATA

Shiai (2007) "Gene Colan

Interview", www.slayerlit.us

MOORE

Matt & Ula Ilnytzky (2011) "Gene Colan:

artist gave life to comic characters", in Boston

Globe, 25 June 2011

SIUNTRES

John (2005) Gene Colan Interview,

transcribed from the podcast Word Balloon: The Comic

Creator's Interview Show , available online at www.wordballoon.libsyn.com

SIUNTRES

John (2006) Marv Wolfman by Night,

transcribed from the podcast Word Balloon: The Comic

Creator's Interview Show , available online at www.wordballoon.libsyn.com

THOMAS

Michael David (2000) "Jim Shooter Interview", www.comicbookresources.com

THOMAS

Roy (2000) "So you want

a Job eh? The Gene Colan Interview", Alter

Ego (vol. 3 issue 6), www.twomorrows.com

|

| |

|

|

| |

The

illustrations presented here are copyright

material. Their reproduction for the review

and research purposes of this website is

considered fair use as set out by the

Copyright Act of 1976, 17

U.S.C. par. 107.

BATMAN and all related elements are the

property of DC Comics, Inc. TM and © DC

Comics, Inc., a subsidiary of Time Warner

Inc.

Scans of original artwork and production art

are from my personal collection.

Text is (c)

2012-2016

The introductory

quote by Gene Colan is from Mata (2007)

page first

uploaded to the web 20 August 2016

|

|