SYNOPSIS The mayoral election race in Gotham is on its last lap, and it looks like a tight race. However, councilman Arthur Reeves is in good spirits, in spite of actually trailing his opponent, business Hamilton Hill, in the late polls, and this is because only a day ago he has been offered a decisive boost out of the blue by someone wishing to remain anonymous - in the form of what he is told to be photographic proof revealing Batman's secret identity... |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| Meanwhile, Lucius Fox is working late at the Wayne Foundation and dumbfounded by seeing the display on his computer screen all of a sudden turn into the graphic of a top hat. But before he can think of a reasonable explanation he is knocked out by an explosion... | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Wayne agrees to pay but immediately visits a couple of shops which he deducts must have sold components to build the explosive device found near Fox's computer. In doing so, he also learns that the Mad Hatter had bought equipment for bio-feedback applications. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| The Mad Hatter naturally accepts and, to the horror of Fox, operates his machine on Batman - which seems to be doing its terrible deed successfully, wiping out the Batman's mind. However, as the Hatter releases the straps from what he presumes to be a now willingless shell the Batman lashes out at him - and foils his plans once again... | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

REVIEW & ANALYSIS DC Comics knew very well what kind of first class comic book penciller they had been able to recruit from Marvel as the editor-in-chief at the House of Ideas, Jim Shooter, had fallen out with Gene Colan and virtually driven him - together with many others - away. Colan had been on long runs of Daredevil (arguably Marvel's most Batman-like character) and received critical acclaim for his superb work on the classic Tomb of Dracula where his moody and shadowy style made the pages come alive. No surprise, therefore, that Dick Giordano asked Colan to draw the Batman both in his own title and in Detective Comics - and Colan's vision of the Darknight Detective was, appropriately, "a very mysterious figure of the night" (Klaehn, 2010), and his art on the Batman is dynamic and captivating and an excellent visual narration of the storyline. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

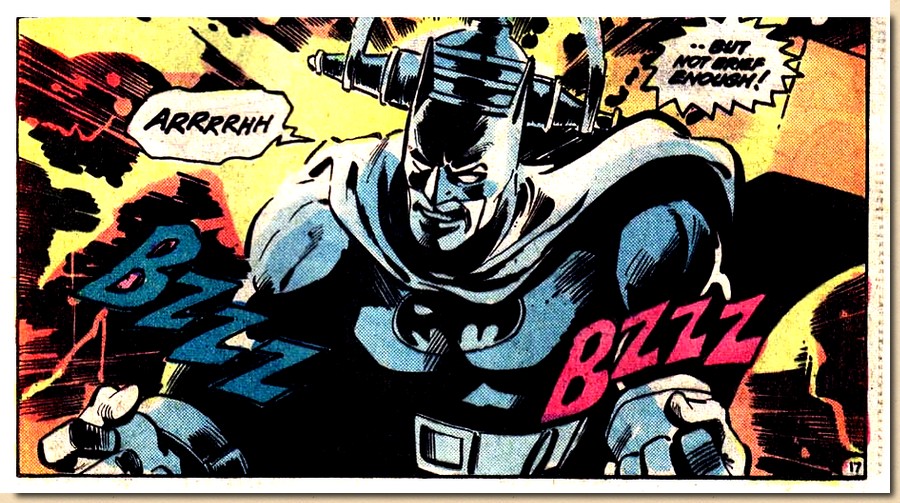

| It creates

a highly realistic yet at the same time mysterious

atmosphere, and it draws the reader in, such as this

panel showing the Batman seemingly subjected to the

terrible effects of the Mad Hatter's bio-feedback

machine. In short: some of the best comic book artwork

you can come across. The only letdown is - it could have

been even better. At least those who knew his art from his Marvel days and, above all, Tomb of Dracula knew that it could have been even more intense, even moodier, even more cinematographic, even darker. The reason for this artifical lid on Colan's art was DC's policy of requiring all artwork to be within the limits of a pre-defined house style, which in this case meant that the inking in most panels was far too light. Gone were most of the dark and looming shadows (which no doubt were there in Colan's pencilled pages) and which Tom Palmer had inked to perfection over at Marvel - gone in spite of the fact that they would have fitted the Batman so very well. Gerry Conway's principal storyline comes across as a clean "done in one" encounter with an old Batman foe in the person of the original Mad Hatter. Always a squeaky character, Conway reveals this to be the original Mad Hatter from way back, and now Batman is up against Tetch's beyond state of the art mind-controlling technology, and somehow all of this bio-feedback and alpha-waves makes sense even if you know it's only comic book science. Having Bruce Wayne do some detective work rather than in the guise of his alter ego is a nice touch, and the fact that Lucius Fox is the actual victim of the Mad Hatter broadens the implications of Conway's storytelling. Batman foils Tetch's plans by using the limitations of his mind-erasing machine's conductivity (which seems pretty much in line with actual real world physics), and the Mad Hatter looks set for yet another prolonged stay at a mental institution. The real strong point of Conway's storytelling, however, is how he weaves two major subplots into the overall plot. First, we have the Damocles sword hanging over the Wayne Foundation in the form of Poison Ivy's hypnotic influence on the board of directors (including Bruce Wayne), placed there by Conway in a story arc preceding Detective Comics #510. The members of the board know that she plans to transfer the foundation's funds to her own accounts but can do nothing because they cannot talk about it due to the hypnotic spell. And secondly we have the looming threat of councilman and majoral candidate Reeves being in possession of information regarding the true identity of Batman and his announcement to make this information public. Both subplots provide an overall threat to Batman which is truly formidable, but he cannot devote himself entirely to this task as he is constantly challenged by other events as well, such as the Mad Hatter highjacking Lucius Fox in this issue. This makes for interesting reading on multiple levels and connects episodic events such as the encounter with the Mad Hatter and weaves them into a much larger picture. As a result, everything gets just that much more interesting and, in a way, more realistic and down to earth, in spite of all the fantastic elements involved in a Batman story. HIGHLY RECOMMENDED READING - interesting story with complex subplot background, excellent artwork |

||||||||

FACTS & FIGURES The Mad Hatter featured in this issue is the original villain, a skilled neuroscientific researcher named Jervis Tetch, who was introduced in Batman #49 with an abundance of references to Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865). Gene Colan left his longtime employer Marvel in 1981 over a series of disputes with editor-in-chief Jim Shooter and turned to DC. His first Batman work appeared in Batman #340 (October 1981), and the "Head-Hunt by a Mad Hatter" was his first artwork to appear in Detective Comics. Unfortunately, Colan soon had to acknowledge that working for DC would not allow him to exploit the full potential of his artistic talents:

The artistic partnership with writer Gerry Conway, on the other hand, was a fruitful one from Conway's perspective:

Following a first hint in Detective Comics #509 and Batman #343, DC instituted a regular plot and storyline cross-over from Detective Comics into Batman as of Detective Comics #510. This procedure effectively created a fortnightly Batman book, with Detective on sale on the second Wednesday of a month and Batman on the fourth. Whilst this running in parallel did not ultimately require readers to buy both books (there would usually be a brief recap of the events in the preceding issue of the other title), reading only one of the two titles could make the storyline become slightly "jumpy" at times. Overall, however, DC did a good job in this not overly easy project. "Head-Hunt by a Mad Hatter" was reprinted in 2011 in the collected edition Gene Colan - Tales of the Batman Vol 1. |

||||||||

THE REVAMP OF A C LIST GOLDEN AGE VILLAIN MAD HATTER IDENTITY - Jervis Tetch |

||||||||

A fair number of Batman rogues which today are labelled as or appear to be "classic old time villains" actually dropped off the radar after their often brief (and sometimes not very impressive) first introduction and only truly became part of the Batman mythology after being rediscovered by authors (and readers) more than twenty or thirty years later. Just like the Scarecrow (who vanished from the ranks of Batman foes following his appearance in Detective Comics #73 in March 1943 and remained unseen for no less than twenty four years until DC Golden Age veterans Gardner Fox and Sheldon Moldoff reintroduced the "Master of Fear" in Batman #189 in February 1967) or Two-Face (who, following five appearances in the 1940s and early 1950s completely disappeared from the Batman universe between 1954 and 1971 until Dennis O'Neil brought him back in Batman #234), the Mad Hatter was originally one of many "revolving door" villains of the 1940s which really were the result of an editorial policy which assumed that readers wanted new villains most of the time (Duncan & Smith, 2013). The chronology of the Mad Hatter's appearances is muddled by the fact that following his first bout with the Darknight Detective in Batman #47 (October 1948), the next appearance (in Detective Comics #230, April 1956) is by an unknown individual who, although claiming to be Jervis Tetch, is actually an impostor who then subsequently appears in a number of Batman stories before the return of the original Mad Hatter in Detective Comics #510. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| But at least from here on the fake Mad Hatter did not reappear until Batman #700 (August 2010) where Grant Morrison, significantly, had him call himself Hatman. | ||||||||

ORIGIN The first appearance of the Mad Hatter falls squarely into a period in Batman's publication history when villains would appear out of the blue, become the main focus of attention of both the Batman and the Police force, and then disappear behind iron bars forever (as far as Batman was concerned) just as quickly. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

The Mad Hatter's theme, not surprisingly, is his hat, in which he alternatively hides a gas pistol or chemicals which he can set alight to create an enormous smokescreen for his escape once Batman and Robin have him cornered. In a final encounter (set on the stage of a production of Alice in Wonderland), the Mad Hatter is brought down not the least thanks to Vicki Vale, who is also introduced in this issue of Batman (and actually receives far more plot and story time than the Mad Hatter) and blinds him when she takes a flash picture of Batman and the hatter fighting it out. As for the identity, motives and reasons behind the Mad Hatter, readers of Batman #49 come away with a total blank. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

EVOLUTION OF THE CHARACTER Following the rather bland first appearance of the Mad Hatter almost eight years passed until he resurfaced in Detective Comics #230 in April 1956 - as a fundamentally different character, albeit again written by Bill Finger (and now pencilled by Sheldon Moldoff). Confusingly enough, however, this is the first time readers actually learn of the Mad Hatter's real name, Jervis Tetch, and his motivation, being a somewhat over the top collector of hats (both presented in the expositionary soliloquy which is par for the course in any Silver Age comic book). |

||||||||

| Taking the cue from his original 1948 story, Finger also had this Mad Hatter produce all kinds of weapons from out of his hats in true magician fashion - in this case ranging from flame throwers to buzzsaws. Essentially, however, this Mad Hatter tries to trick Batman - which he partially succeeds in after contaminating the cowl with a radioactive substance which then forces Batman to discard it (unseen). However, the radioactivity then functions as a tracer for the Dynamic Duo who thus find the Hatter's hideout, take him down, and send him to a long spell in Gotham prison. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

|

||||||||

| After those two television appearances, the Mad Hatter disappeared once more, and he would be absent from the Batman comic books for no less than 22 years. He did finally return in Batman #297 (March 1978), written by David Vern Reed and pencilled by Rich Buckler, in "The Mad Hatter goes straight" - a story title which was made to sound dubious by the cover blurb "Death wears 1,000 different hats when the Mad hatter strikes!" | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| A quaintly entertaining story which pushed the "themed villain" concept to its tongue-in-cheek limits, it still featured the "impostor" but added nothing to the characterisation as the Mad Hatter is portrayed as nothing more than a mentally off-balance criminal who has a bee in his bonnet about hats. Essentially, the Mad Hatter - both original and impostor - had been left without both an origin and some depth of personality by Bill Finger and consecutive handlers ever since his first appearance in Batman #49 in October 1948. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| While Marvel had picked up speed with a growingly more mature readership, DC was still putting out very "clean" and fairly simple stories which more often than not ran for one or two issues only and with minimal (if any) consequences for the next plot. As the Marvel Universe got more complex, DC seemed stuck in ultimate rewind. But as Gerry Conway came on board, Dick Giordano was planning to change things at least for the two Batman titles by running them in sync, ultimately as though it were one fortnightly comic book, and this gave Conway the chance to essentially write the Darknight Detective after a brief run-in period as though he were a Marvel character. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| As such Conway probably wanted to make sure that any memories of the simpleton hat collector were put aside, and therefore retroactively labelled all previous appearances other than the first as the work of an impostor. And almost as though to make a point, Conway has the Original stating that he "disposed" of the identity thief. Other than that, however, there still was no background story attached which explained who Jervis Tetch actually was. | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| The drama unfolds when he

falls in love with his secretary, Alice Pleasance, who

does not, however, reciprocate his feelings. When her

boyfriend leaves her, Tetch turns up in a dashing attire

(i.e. the way we know the Mad Hatter to dress) and

attempts to win Alice's affection by taking her out for a

night on the town. She misinterprets the gesture as

simply a way to cheer her up, and thus unwittingly spurns

his affections. Driven over the edge, he uses his mind

control devices to turn Alice into his robot-like puppet

in an Alice in Wonderland setting in which, ultimately,

Batman defeats the Mad Hatter and breaks the control he

had over Alice. By providing this background and origin, Dini finally gave the character the depth it needed. Appearing in three additional episodes, Batman: The Animated Series brought out the full potential of the Mad Hatter: a fundamentally sad story featuring a lonely person who takes on a decidedly rough edge when he uses his intellectual wit to dominate others and rob them of their free will. With Conway, the Mad Hatter had stopped being cheesy, and Dini gave him weight and a malicious twist. From here on, things just got darker and more vicious as subsequent writers increasingly presented the character as being a psychotic and dangerous homicidal who succumbs to his delusional ideas. |

||||||||

| In the pivotal 1993 Knightfall

saga (which culminates in the famous "breaking"

of the Batman by Bane) the Mad Hatter is the first to

strike following the massive breakout of Arkham. He is

still true to his set manners, however, as he invites all

criminals to a tea party where he feels sure Batman and

Robin will show up too. And there's still a trait of

charm when he hides his mind-controlling implants in

"free coffee and donuts" tickets which he hands

out, of all places, in front of the police stations in

Gotham in Gotham Central. But with the 2011 "New 52" reboot, the Mad Hatter took a deep and dark plunge. |

||||||||

|

||||||||

| It's certainly a long way from Batman's world as depicted by Gerry Conway and Gene Colan in Detective Comics #510, and whilst the Mad Hatter lost his goofiness back in 1982, he has now lost all innocence and indeed all charm in recent years. | ||||||||

BIBLIOGRAPHY DAUDT Ron E. (N.A.) "Gerry Conway Interview", www.wtv-zone.com KLAEHN Jefferey (2010) "Gene Colan Interview", jefferyklaehn.blogspot.com ROGERS Vaneta (2013) "Hurrwitz, Van Scyver debut 'perverse' horrific Mad Hatter", newsarama.com |

||||||||

|

BATMAN and all related elements are

the property of DC Comics, Inc. TM and © DC Comics,

Inc., a subsidiary of Time Warner Inc.

uploaded to the web 30 September 2016 |