SYNOPSIS

!

SPOILER ALERT !

Victor Von

Doom is once again in search of the rare

and powerful metal ore Vibranium, and

because this precious metal can only be

found in Wakanda, Dr Doom once again

focuses on this hidden African kingdom

(just as he had done so previously in Astonishing Tales

#6).

But unlike that 1971 invasion of Wakanda,

Doom applies a far more subtle approach

this time around by essentially

masterminding a political coup which

overthrows the royal family of Wakanda

and enables him to take control of the

kingdom.

In Doomwar

#2, the second of a total of six issues,

the X-Men have arrived to help T'Challa

and the Black Panther (at this point in

time T'Challa's sister Shuri is the

Panther) regain a foothold in what is now

a Wakanda conquered and controlled by Dr.

Doom with the aid of local rebels. It is,

however, precisely the savageness with

which Shuri acts towards these groups of

her own people which starts to make the

X-Men feel more than just uneasy.

When

T'Challa makes it to the vibranium vault

he finds Dr. Doom at an impasse, as even

Storm (T'Challa's wife) cannot open the

final lock. Seizing the opportunity now

arisen, Doom leaves T'Challa with a

choice which is both simple and sinister:

either T'Challa's wife dies or he gives

up the secret of the vault.

Not

surprisingly, T'Challa chooses the latter

option... (to be continued)

|

|

Doomwar #2

(May 2010)

|

|

|

| |

| |

REVIEW & ANALYSIS

2010 was a year

which saw Marvel throw an extraordinary number of cross-overs

at readers. The main focus and publicity output was on

"Siege" (which

saw Norman Osborn invade Asgard in the aftermath of yet

another crossover, "Dark Reign"), which then led into

"Heroic Age" (which saw Norman Osborn

defeated). Other cross-overs which were milked almost to

the breaking point with special and single issues in 2010

were "Shadowland" and "Chaos War".

But that was by no

means all. Minor" crossovers and "event

storylines" were "Realm of Kings",

"World War Hulks", "Second Coming",

"Thanos Imperative", "Curse of the

Mutants" - and "Doomwar". Given that none

of the big names of the time worked on Doomwar

it is hardly surprising that the six issues somewhat flew

underneath the radar amongst all the publicity clatter

put out by the House of Ideas to promote (some would say

hype) their "big names and big themes"

crossovers and limited series.

|

| |

|

|

Which

is a shame. Even though Doomwar

received some very unfavourable comments

at the time, there were also those who

saw the strong points. Possibly the main

weakness was an overdose of super heroes

involved in the story, the combined

actions of which were at times somewhat

all over the place - in order to help

T'Challa and the Black Panther regain

control of Wakanda, no less than the

X-Men plus the Fantastic Four plus War

Machine plus Deadpool descended on the

African kingdom. Maybe it was the sales

desk's idea, hoping to attract attention

through this "more bang for your

bucks" formula, or maybe it was

writer Jonathan Maberry's bona fide idea

that it would energize the story.

Whichever it was, it didn't work.

What Maberry

got spot on, however, was the portrayal

of Dr Doom. The character has come a long

way since his debut in Fantastic Four

#5 (July 1962) where he was in essence a

vagrant madman who seemingly built

castles and machines of destruction all

by himself.

Only given

an actual origin story in Fantastic

Four Annual #2 (September 1964) he

was quickly promoted to being the leader

of a fictional state (Latveria) situated

in the Carpathian Mountains of Eastern

Europe, making him much more than just a

villain - he now was a dictator, and it

literally put him on the map of the world

which ultimately he sought to conquer and

rule.

|

|

|

| |

However, it also makes the

character a lot more ambivalent than any regular villain,

as Stan Lee himself pointed out many times:

"Everybody has

Doctor Doom misunderstood. Everybody thinks he's a

criminal, but all he wants is to rule the world. Now,

if you really think about it objectively, you could

walk up to a policeman, and you could say, 'Excuse

me, officer, I want to tell you something: I want to

rule the world.' He can't arrest you; it's not a

crime to want to rule the world." (Stan Lee

in Ricci, 2016)

|

| |

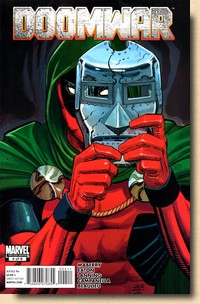

Doomwar #1 (of 6)

(April 2010)

|

|

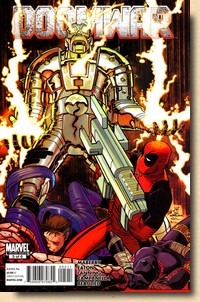

Doomwar #2

(May 2010)

|

|

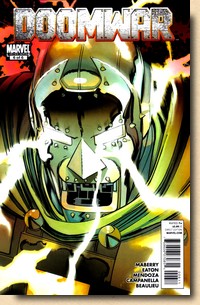

Doomwar #3

(June 2010)

|

|

Doomwar #4

(July 2010)

|

|

|

|

| |

Doomwar #5

(August 2010)

|

|

Doomwar #6

(September 2010)

|

|

"So

[...] it's unfair that he's

considered a villain, because

he just wants to rule the

world. Then maybe he could do

a better job of it. So I'm

very interested in Doctor

Doom, and I'd like to clear

his name." (Stan

Lee in Ricci, 2016)

Originally

written by Stan Lee as an

extremely arrogant person in the

1960s and early 1970s (which

ultimately would always lead to

the downfall of his schemes), he

became a more complex character

as of the late 1970s, with a

complicated background which

included a harsh upbringing and

the trauma of facial

disfiguration.

Maberry

latched on to this very well,

exploring the mental (im)balance

of a Dr Doom who - not unlike the

classic Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

juxtaposition - is constantly

slipping away just when you

thought you could put a label on

him.

|

|

|

|

| |

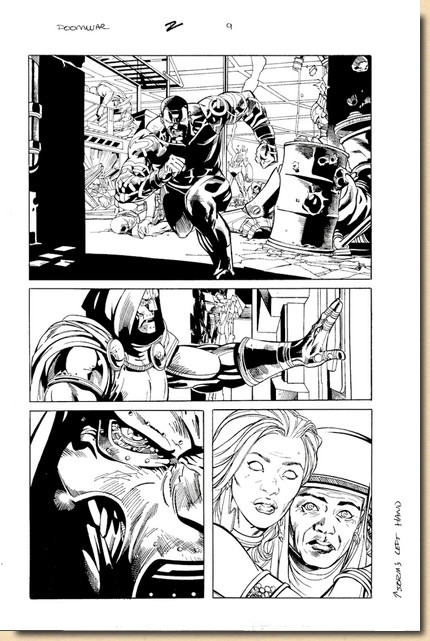

| Although always a matter of

taste, the artwork of Doomsday came across very

strong too, courtesy of penciller Scot Eaton and inkers Andy Lanning and

Robert Campanella. Eaton started working as a freelance artist

in the 1990s and has since worked for all of the major US

publishers. He drew well-known Marvel characters under

contract between 2005 and 2013 such as Captain America,

Thor, Spider-Man and the X-Men, and also put in a

significant amount of freelance work for DC, including

fan favourites such as the Batman, Swamp Thing and Green

Lantern. Eaton also worked on Crossgen's Sigil. His

powerful style which comes across the pages as being very

atmospheric and cinematographic in its rendition and

composition really gave Doom (and all the other

characters) the weight and presence needed.

|

| |

Original

artwork by Scot Eaton (pencils) and Andy Lanning &

Robert Campanella (inks)

for page 9 of Doomwar #2 (scanned from the original) -

and the same page as it appeared in print

|

| |

FACTS & NUMBERS

|

| |

|

|

Given

the already mentioned somewhat reduced

publicity presence, the sales figures to

comic book stores for Doomwar #1

weren't too bad at just over 43,000

copies, making it the 33rd best selling

comic book of February 2010 - the

bestselling book being DC's Blackest

Night #7 with 130,000 copies

followed by Marvel's Siege #2 in

second place with 108,500 copies. Two variant covers

certainly pushed the sales a bit, but as

of Doomwar #2 the numbers were

going down, as is so often the case with

limited series.

While the

second issue still sold 30,500 copies,

this decreased slightly to roughly 28,000

each for issues 3 and 4. The two final

issues sold 26,000 (Doomwar #5)

and 25,000 (Doomwar #6) copies.

Overall these numbers didn't look too

bad, given that the length of the

mini-series (six issues) clearly pointed

to a collected edition - which in 2010

had become the central publishing concept

anyway. Published in October 2010, this

turned out to be a 144 page count

hardcover (Doomwar, ISBN

978-0-7851-4714-5) rather than just

another "trade paperback".

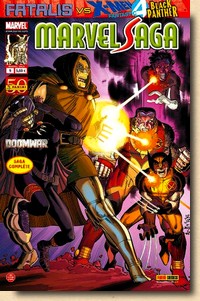

The entire

six issues of Doomwar were also

reprinted by Panini for the French market

in February 2011 in Marvel Saga

#9.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY RICCI K.J. (2016)

"Stan Lee Interview", Cat Country Youtube

Channel, 12 November 2016

|

| |

| |

The illustrations

presented here are copyright material.

Their reproduction for the review and

research purposes of this website is

considered fair use

as set out by the Copyright Act of 1976,

17 U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2019

|

|

|

|