|

|

FABULOUS

100TH

ISSUES

HOW

COMIC BOOK COVERS

CELEBRATE CENTENARIES

THE

GOLDEN AGE (1938-1956)

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Comic books come in many

different forms and sizes, but there's one thing (almost)

all of them have in common: they're numbered, and the

numbering is continuous (unlike most periodicals and

magazines, which often had their numbering broken down

into annual volumes. |

| |

| The

reason for the continuous numbering is linked by

several sources (e.g. Miller, 2011) to the comic

book's ancestral roots in the Penny Dreadfuls,

Dime Novels and Pulps of the late 18th and early 19th century, all of which also

used a continuous numbering system. One might

assume that it must have felt like a logical

choice for publishers of the new comic book

format in the 1930s. But whereas the system used

was generally the same, the way the number of a

comic book issue was displayed varied greatly

from publisher to publisher.

In some cases it

featured prominently on the cover (a system which

evolved into specific placeholders and would

eventually also include month, price and even

additional information), in others the issue

number was hidden in the indicia at the bottom of

the first page or even coded (as was the case

with Dell's titles).

It seems however

safe to assume that, at least initially, the

ongoing numbering of issues of a given comic book

title served the organisational needs of editors,

publishers and distributors more than it ever

really served a purpose for readers.

|

|

|

|

| |

| This was certainly true for

as long as individual issues of comic books were

self-contained, meaning they could really be read in no

specific order at all. Things only changed when

continuity was introduced and a growing base of regular

readers-turned-fans evolved. This would be especially

true for Marvel Comics, of course, where readers not only

knew what happened several issues ago but were quite

often reminded of that fact by way of an editorial

footnote. Numbers also

have a psychological effect, of course. In the case of

comic books, popular wisdom has it that newsagents and

other points of sale preferred titles with higher issue

numbers, indicating an established brand. And many comic

book titles certainly were racking up the issue count by

the mid-1950s, although not always for reasons of brand

stability. In fact, sometimes it was for outright

opposite reasons.

"Paul

Levitz once suggested to me that one reason so

many titles simply changed names rather than started

anew at #1 was logistical. It was easier for a

publisher to change the title on a series than get a

new one set up [with his] printer’s and [...]

distributor’s systems." (Miller, 2011)

|

| |

|

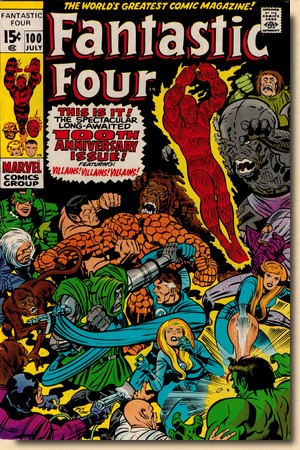

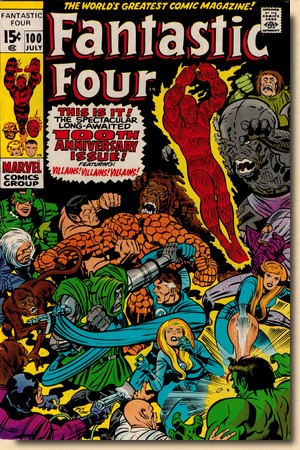

Fantastic

Four #100 (July 1970)

|

|

As a result,

comic books changed their title

several times while simply

keeping the original numbering -

but this was by no means

restricted to the 1940s and

1950s, as the example of Marvel's

Fantasy

Masterpieces illustrates:

issue #11 (October 1967) was

followed two months later not by Fantasy

Masterpieces #12 but rather Marvel

Super-Heroes #12 (December

1967) - new title, continued

sequential numbering.

These days,

things are different, as a

seemingly never-ending succession

of reboots and subsequent first

issues from publishers across the

board shows that nothing sells

quite like a #1 issue. But what

about centenary issues? That

moment when a title reaches three

digits in its numbering for the

first time?

Fantastic

Four #100, cover dated July

1970, was the first of Marvel's

superhero titles to reach the one

hundred issues mark in actual

numbering, i.e. without any

changes to title or character

content, and its Jack Kirby cover

is what Marvel fans would come to

expect for such an occasion:

crammed with good guys and bad

guys and a blurb that proclaims "THIS

IS IT! THE SPECTACULAR

LONG-AWAITED 100th ANNIVERSARY

ISSUE!".

However, the

anniversary fireworks were

limited to the cover - rather

surprisingly (given Marvel's

pronounced tendency towards

self-celebration), both Stan

Lee's Soapbox and the Bullpen

Bulletin lost not a word on the

occasion.

Did comic

books quite simply not celebrate

centenaries other than on their

covers? A look back in time,

starting here with the so-called

Golden Age (1938-1956), provides

some contradicting answers to

this question.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

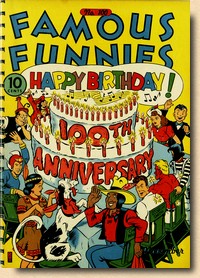

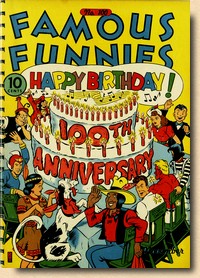

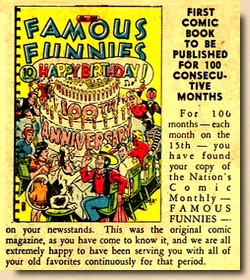

| Famous Funnies,

published monthly since July 1934 and considered by many

scholars and fans alike to be the first true American

comic book title, was the first to reach the centenary

benchmark, and publisher Eastern Color/Famous Funnies

Inc. certainly celebrated that fact in style in October

1941, with a cover that made absolutely certain readers

couldn't miss the milestone occasion of the title's "100th

Anniversary". |

| |

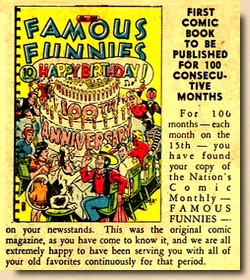

Famous

Funnies #100 Famous

Funnies #100

(Eastern Color, October 1941)

|

|

The cover was made to almost

look like an invitation to a birthday party (one

where all the various characters featured in Famous

Funnies were present at), and editorial

acknowledged the anniversary on the letters page,

proudly pointing out that this was the "first

comic to be published for 100 consecutive

months".

Thanking

readers for their loyalty, editorial also noted

that "we are looking forward to enjoying

with you the time when FAMOUS FUNNIES will have

been published continuously for 200 months instad

of 100 months".

That

wish would be granted - the title would continue

in publication for a total of 218 issues before

cancellation hit in July 1955.

So did Famous

Funnies set the tone for future centennial

comic books and their covers?

|

|

Famous Funnies #100

|

|

| |

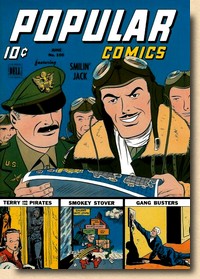

Well, not

really.

Dell was the

next publisher with one hundred issues of a title on its

hand,in June 1944, but when Popular Comics

(first published in February 1936) achieved that feat,

there wasn't even the mildest hint of any celebrations,

with the issue number #100 on the cover being all there

was to it.

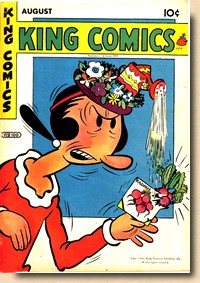

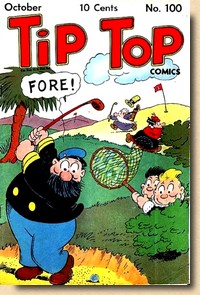

And the same

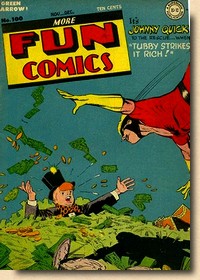

maxed out understatement could be seen with the three

other titles reaching 100 issues in 1944: King

Comics, Tip Top Comics, and More Fun Comics

(which was the first DC title to reach that benchmark,

featuring Aquaman and Green Arrow, both introduced in

issue #73).

|

| |

Popular

Comics #100 Popular

Comics #100

(Dell, June 1944)

|

|

King Comics #100

(David McKay, August 1944)

|

|

Tip Top Comics #100

(United Feature, October 1944)

|

|

More Fun Comics #100

(DC, November 1944)

|

|

| |

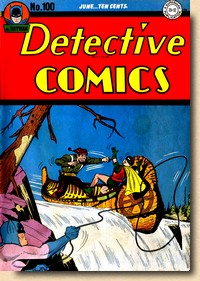

| The next big title to

celebrate its centenary was Detective Comics

in June 1945 - except Detective Comics

#100 didn't really celebrate anything, with not a

single word mentioning the occasion anywhere -

not even on the cover, which on top of it all

featured the Batman squeezed into the bottom left

corner and wearing a rather peculiarly pinkish

outfit. Clearly,

Famous Funnies #100 had been an

exception, and the general rule in the comic book

industry of the 1940s was to simply ignore

centenaries.

The major reason for

this lacklustre handling of anniversary issues

may well be rooted in the fact that before the

rise of fandom and a newly gained

self-confidence, comic book publishers and

artists as well as distributors saw comic books

as one of the ultimate cheap and disposable

entertainment forms. Readers came and went, and

the stories in each issue were unconnected other

than through the main characters (e.g. Batman and

Robin), so why even bother?

As the 1940s

progressed, more and more comic book titles

reached number 100 in their issue count, but none

of them made the least effort to mark this as a

"special issue". In terms of sales, it

simply wouldn't have made a difference at the

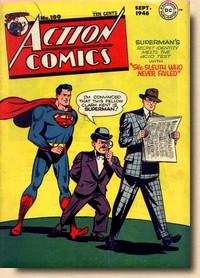

time. Accordingly, neither DC's Adventure

Comics #100 (October 1945) nor Action

Comics #100 (September 1946) make any

mention of the centenary, be it on their covers

or their interior pages.

|

|

Detective Comics #100

(DC, June 1945)

|

|

| |

Adventure

Comics #100 Adventure

Comics #100

(DC, October 1945)

|

|

Action Comics #100

(DC, September 1946)

|

|

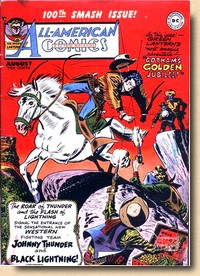

All-American Comics #100

(DC, August 1948)

|

|

However, DC did break the

established centenary silence in August 1948, by

proclaiming All-American Comics #100

(starring Johnny Thunder as well as the Golden

Age Green Lantern, Dr Mid-Nite, and Atom) to be a

"100th SMASH ISSUE!" - only

the second cover to do so after Eastern Color's Famous

Funnies #100 in October 1941.

As a

sidenote, DC had purchased this title from

All-American Comics only two years prior - and it

would become All-American Western as of

issue #103.

|

|

| |

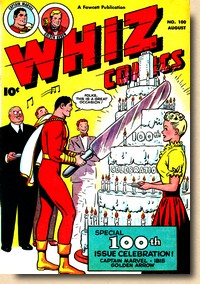

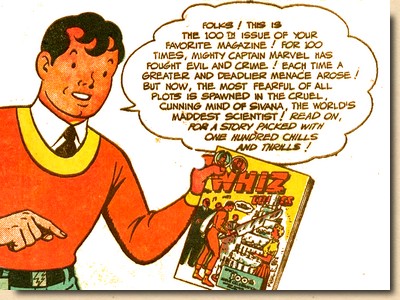

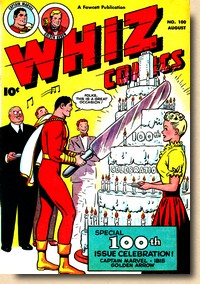

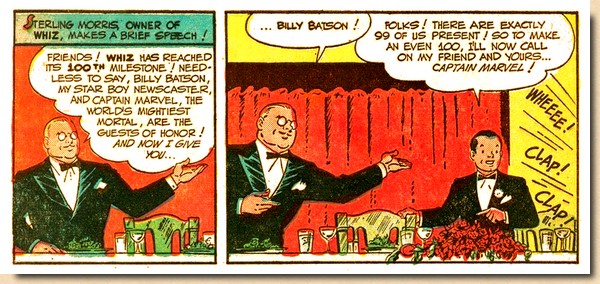

| At this point in time,

centenary issues started to hit the newsstands at a

regular pace, and the next in line after All-American

Comics #100 was Whiz Comics #100, also in

August 1948. But whereas DC had been content with a top

of the cover banner, Fawcett retraced the footsteps of Famous

Funnies #100 when Whiz Comics #100 also

featured a birthday cake on its cover. |

| |

Whiz

Comics #100 Whiz

Comics #100

(Fawcett, August 1948)

|

|

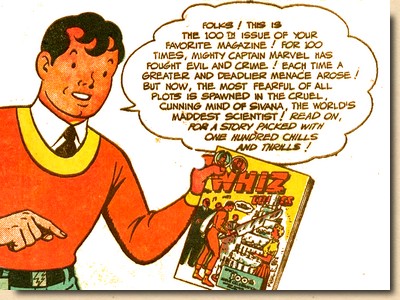

But that wasn't it - taking

matters even a few steps further than Famous

Funnies #100 back in 1941, Whiz Comics #100

was full of references to the centenary.

An

editorial shout out on the back of the inside

cover was followed by a Captain Marvel story

which kicked off with the publishers of Whiz

Comics hosting an anniversary gala, which

served as an opening to a story full of constant

references to the number 100.

99

guests at the gala dinner are joined by Captain

Marvel's archenemy Sivana, who is described as "100

villains rolled into one".

|

|

Whiz Comics #100

|

|

| |

|

|

Writer Otto

Binder really piled it on with

his story, and as a result,

"The Hundred Horrors"

is not only clearly a 100th

anniversary story, but also the

very first.

While other

publishers were flat out ignoring

their titles' centenaries,

Fawcett had a really good go at

it.

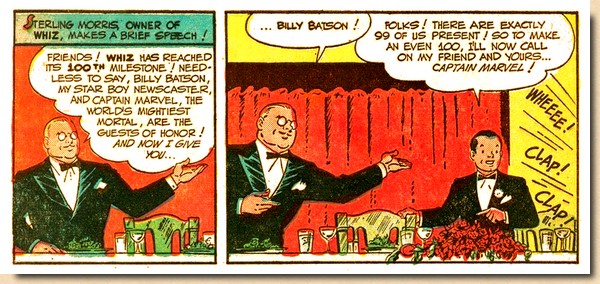

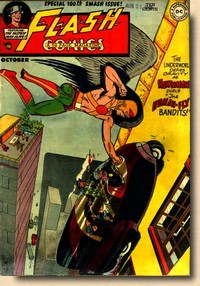

Two months

later, for the October 1948

publication run, it was once

again DC who had their next title

clocking up 100 issues, this time

with Flash Comics #100.

|

|

|

|

| |

| But just as with All-American

Comics #100 two months prior, the only indication of

a centenary anniversary was restricted to a banner at the

top of the cover, albeit this "100th SMASH

ISSUE!" was now also "SPECIAL". |

| |

Flash Comics #100

(DC, October 1948)

|

|

But that was it. No editorial

celebrations, and the stories featured in Flash

Comics #100 were classic standalone plots

that could have been printed in any issue of that

title.

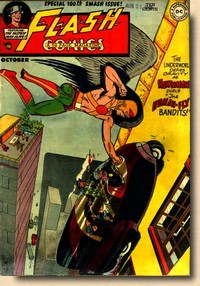

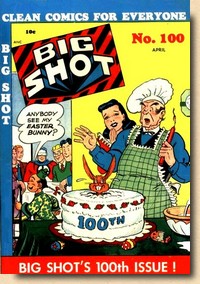

The

next two titles to reach their cenetenaries -

Wings Comics #100 from Fiction House in

December 1948 and Master Comics #100

from Fawcett in February 1949 - kept total radio

silence about their anniversary, and it wasn't

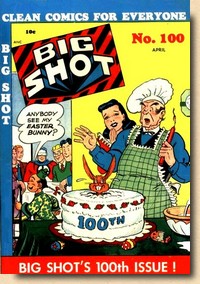

until April 1949 and Columbia's Big Shot #100

that comic book readers got to see another

birthday cake cover on the newsstands.

Strett

& Smith, the next publisher with a centenary

issue on their hands, kept total silence about

this fact in Shadow Comics #100 (July

1949), but the last 100th anniversary title of

the 1940s did just the opposite - maybe not

surprising since it was once again published by

Fawcett and once again featured Captain Marvel.

|

|

Big

Shot #100 Big

Shot #100

(Columbia, April 1949)

|

|

| |

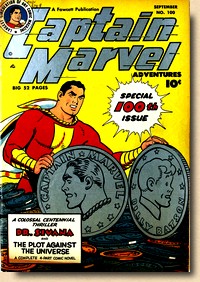

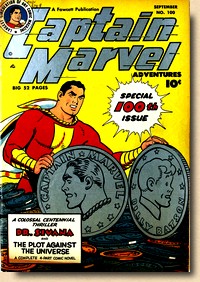

Once again scripted by Otto

Binder, Captain Marvel's "anniversary

story" (a four part tale spread out over 33

pages) didn't quite go as far as his previous

centenary adventure in Whiz Comics #100

a year prior to Captain Marvel Adventures #100

(September 1949). This time, the references were

kept to the first and final panels, used as a

"framing device" rather than a plot

element.

|

|

Captain

Marvel Adventures #100 Captain

Marvel Adventures #100

(Fawcett, September 1949)

|

|

| |

| At the time, Fawcett's

titles featuring Captain Marvel sold well over a million

copies each every month, so it made perfect marketing

sense to let readers know about landmark issue

achievements and to "bond" with them (an

approach elevated to an artform later on, in the 1960s,

by Stan Lee). For other titles, the reality at the

newsstand was such that they sold well enough, but

nowhere enough to trump up anything. This was also the case for the first

centenary issue of the 1950s, DC's Star Spangled

Comics #100 (January 1950). Even though Robin

"the Boy Wonder" had a solo feature in this

title since February 1947, there was no centenary

indication to be found. The same held true for Looney

Tunes and Merrie Melodies Comics #100 (Dell,

February 1950), Police Comics #100 (Quality

Comics, June 1950) and Modern Comics #100

(Quality Comics, August 1950).

A somewhat unusual approach

to having a #100 issue was taken by UK publisher L.

Miller & Son in April 1950 when they launched their

British market Fawcett reprint title Captain Midnight

by starting the issue count at 100 rather than 1 -

definitely a somewhat rushed centenary (which however,

and perhaps understandably so, did without any cover

fanfare). It was not, however, to be the only time a

publisher opted for this kind of advanced numbering

scheme - US publisher Toby launched their short-lived Buck

Rogers comic in Janaury 1951 with issue #100.

|

| |

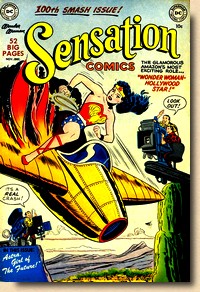

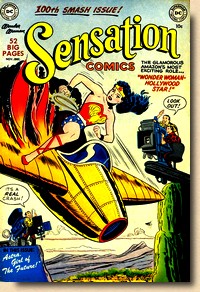

Sensation Comics #100

(DC, November 1950)

|

|

DC's Sensation Comics

#100 (November/December 1950), featuring Wonder

Woman and three additional features with female

heroines, marked a return to the cover blurb "100th

SMASH ISSUE!", but as before, editors

at DC did not think the occasion worthy of

anything more.

By the

very early 1950s, a number of centennial issues

were hitting the newsstands which were examples

of the continued numbering of a comic book which

had undergone one or more title changes in the

process.

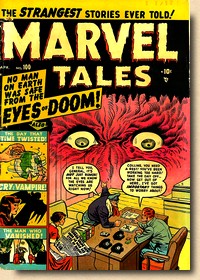

Such

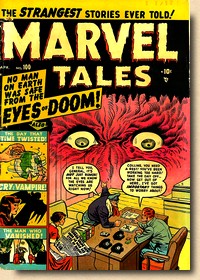

was the case with Marvel Tales #100

(April 1951), which only existed as a title since

issue #93 as it continued the numbering of Marvel

Mystery Comics (#2-91), which in turn had

started out as Marvel Comics #1 in October 1939.

Whilst

therefore not in an uninterrupted original title

numbering sequence, Marvel Tales #100

was nonetheless the first Marvel title to reach a

centenary.

|

|

Marvel

Tales #100 Marvel

Tales #100

(Marvel, April 1951)

|

|

| |

| A certain Stan Lee was

already at the editor's helm, but he had yet to develop

his special style in relating to readers - and as a

result, not a word other than the numbering on the cover

was lost on this occasion. A similarly "mixed title"

centenary occured in June 1951 when Fawcett's Sweethearts

#100 hit the newsstands. A monthly romance title, it had

started out as Captain Midnight (#1-67), and

inspite of the change from superhero to romance title,

Fawcett kept the numbering going - providing a striking

illustration to Paul Levitz's previously mentioned

assessment that "it was easier for a publisher

to change the title on a series than get a new one set

up" with his distributor (Miller, 2011).

Another example was Lev Gleason's Crime Does Not Pay

#100 (July 1951), which had been called Silver Streak

for its first 21 issues.

Another true (i.e.

continuous numbering on the same title) centenary took

place with Sparkler Comics #100 in July 1951,

but as so many publishers before, United Feature didn't

deem the occasion worthy of any mentioning on the cover,

let alone on any editorial interior page.

|

| |

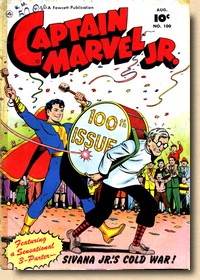

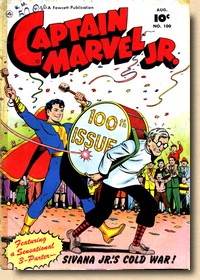

| August 1951 saw yet another

of Fawcett's range of Captain Marvel titles reach

its centenial, but while the cover of Captain Marvel

Jr #100 was literally banging its drum about

the event, no further mentioning of it was made

in the interior pages, and the "sensational

3-parter" story featuring the teenage

equivalents of Captain Marvel and his arch-enemy

Sivana carried no puns or references either. Maybe the change of

writer had

something to do with it (Otto Binder had been in

charge of both the Captain Marvel centenary

stories, in Whiz

Comics #100 and Captain Marvel

Adventures #100 in 1948 and 1949

respectively, but Bill Woolfolk was in charge of Captain Marvel

Jr #100). but it is more likely that

editorial just didn't feel like it.

Fawcett had

just won the copyright infringement lawsuit that

National (DC) had initiated (alleging that

Captain Marvel was based on Superman), but at the

same time the popularity of superheroes was in a

stark decline. The drop in the sales figures of

their titles, which by 1949 only amounted to half

of what they had been during the war years

(Wright, 2001), had publishers scrambling to find

new genres which would bring readers back to the

newsstands. On top of this, DC's appeal regarding

the copyright infringement decision was

successful, all of which would lead Fawcett to shut down its entire

comics division in the autumn of 1953.

|

|

Captain

Marvel Jr #100 Captain

Marvel Jr #100

(Fawcett, August 1951)

|

|

| |

Fredric Wertham

(1895 - 1981)

|

|

But the comic book industry

was facing more than just hard times - it was

staring at nothing less than the possibility of

its eradication.

Fredric Wertham, a psychiatrist

from New York, had initiated his crusade against

comic books - which in his eyes were the prime

source of juvenile delinquency - in 1948, and by

1951 he was whipping public opinion into a

frenzy. His calculated (and ultimately also

deceitful) shaming and blaming would lead to the

infamous 1954 senate hearings and the subsequent

creation of the Comics Code Authority. The

afterglow of Wertham's crusade, however, could be

felt for years.

"In the post-war era

of McCarthyism, comics were an attractive

target for grand-standing politicians eager

for villains. Publishers were raided by the

police, titles were outlawed in dozens of

states, and some communities held public

comic-book burnings. (...) Comic sales

plummeted, hundreds of artists and writers

lost their jobs." (Staley, 2018)

|

|

| |

| By the early 1950s, comic

book publishers had

very little to celebrate, and centenary issues certainly

weren't one of those things, especially given the

outright disinterest most publishers had displayed

towards them previously. Hence, the next few centenary

issues published continued the tradition of having no

mention of the occasion whatsoever. The titles in

question were also further prime examples of how the

comic book industry was trying to adapt to the changing

times by changing titles and, more and more often,

content. Red

Ryder Comics #100, published by Dell in November

1951, had originally been published by Hawley for six

issues before being taken over by Dell, who would change

the title to Red Ryder Magazine as of issue

#145; with issue #149 it became Red Ryder Ranch Comic

before merging into Four Color #916.

|

| |

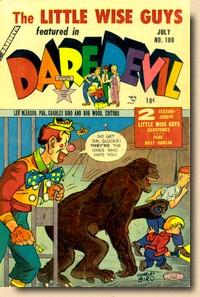

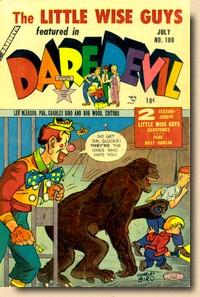

| October 1952 saw the

centenary issue of Gilbert's Classics

Illustrated (with a rendering of Mutiny on

the Bounty but no hint at the special issue

number), followed by Dell's Tom & Jerry

Comics #100 in November 1952; the latter

title had started out as Our Gang Comics

(#1-39) and then Our Gang with Tom &

Jerry (#40-59). In April 1953

St. John published Paul

Terry’s Comics #100, followed in July

by Lev Gleason's Daredevil Comics #100.

Neither of the two made any reference to the

number count benchmark, but the cover of Daredevil

did feature a sign of the times: the Association

of Comics Magazines Publishers (ACMP)

"comics code" star emblem.

Formed

in 1948 by founding members Lev Gleason, Bill

Gaines (EC Comics), Harolod Moore (Famous

Funnies), and Rae Herman (Orbit

Publications), the ACMP's "Publishers

Code", drawing heavily on the Hollywood

"Production Code" (better known as the

"Hays Code") which had been drafted in

similar circumstances, i.e. to stave off external

regulation.

Daredevil

Comics in itself was also a telltale

showcase of the changing times within the comic

book industry - once a superhero comic book

(where the hero, Daredevil, had battled Hitler in

its premier issue back in 1941), it had dropped

one of the Golden Age's most acclaimed masked

hero for comedy in 1950, simply adding the

"Little Wise Guys" to the original

title.

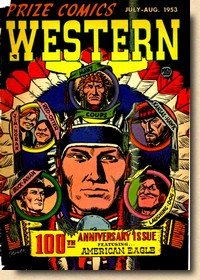

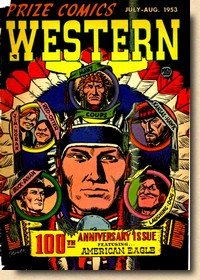

That same month,

Prize's bi-monthly (July-August 1953) Prize

Comics Western #100 featured a special

centenary cover pencilled and inked by John

Severin - though that was the only tip of the hat

to the occasion to be found in the entire comic

book.

August 1953 saw yet

another centenary issue with K.K. Publishing's Boys'

and Girls' March of Comics #100. The

somewhat cumbersome title started out in 1946 as Boys'

and Girls' Comics and covered a whole range

of different genres; while issue #100 featured a

Roy Rogers cover and different advertising

banners (taking up one third of the cover and

differing by region), no special mention of the

centenary occasion was made.

Archie Comics was

next in the line of centenary issues with Pep

Comics #100 in November 1953 - and like most

titles accumulating one hundred issues at that

time simply ignored the fact. The cover did,

however, feature Archie Comics' very own

"approved reading" stamp - a sign of

the times and the ever tightening stranglehold

which comic book publishers found themselves in

as certain circles were pushing harder and harder

to have many titles oulawed and banned.

|

|

Daredevil

Comics #100 Daredevil

Comics #100

(Lev Gleason, July 1953)

Prize

Comics Western #100 Prize

Comics Western #100

(Prize, July/August 1953)

|

|

| |

| Although the (televised)

hearings of

the United States Senate Subcommittee Investigating

Juvenile Delinquency dealing with comic books would only

take place in April 1954, Wertham's anti-comics crusade

had gathered enormous speed since 1950, and although the

Senate hearing was to focus only on horror and crime

comic books, publishers were scrambling to make sure they

would not wake up one morning and find themselves on the

wrong side of the line which Wertham was drawing. DC

Comics had a panel of educational and psychological

experts which were highly advertised on inside covers as

a reassurance to parents that the contents of DC's comic

books were checked and safe; other publishers had the

ACMP Star, and yet others, such as Archie, came up with

their own stamp of approval. |

| |

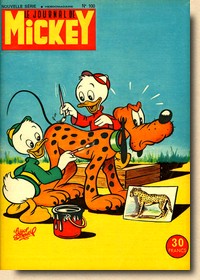

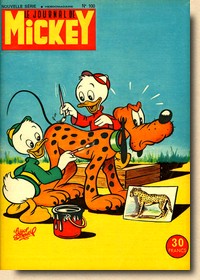

Journal

De Mickey #100 Journal

De Mickey #100

(Hachette, April 1954)

|

|

By the time 1954 rolled

around, many publishers outside the US also

started seeing centenary issues of their titles

(which in most cases reprinted US material). In

Australia, Feature's Adventurs of Brick

Bradford #100 hit the newsagents in January

1954 (featuring newspaper strips reprinted in

comic book format by King in the USA); in France,

Hachette's Journal de Mickey #100 came

out in April 1954 (featuring Disney material

reprints, this title is still being published

today, with the current issue count over the 3500

mark); and in Italy, Mondadori published Topolino

#100 (also a Disney material reprint title which

would run until 1988). None of these titles'

covers featured even the slightest celebratory

mention of the fact that they had reached their

100th issue.

Back in

the US, Gleason let another centenary pass by

silently in April 1954 with Boy Comics #100,

as did Archie Comics in August 1954 when they

published Suzie Comics #100. Silence, it

seems, was considered truly golden when it came

to centenaries - but then it was generally a

time, as pointed out, for comic book publishers

to try and fly under the radar.

This modus

operandi continued in 1955 with ACG's Teepee

Tim #100 (which today would probably be

spelled Tipi in order to avoid

embarrassing associations) which featured a very

bland cover with, no surprise, not even a hint as

to the title's special issue number.

|

|

| |

| ACG stuck to this procedure

when only two months later, when March/April 1955 saw the

publication of Spencer Spook #100 - although in

this case it was somewhat understandable, given the fact

that this comic book had for 99 issues carried the title

Giggle Comics. DC Comics published its next

centenary issue in April 1955 with Hopalong Cassidy

#100; acquired from the now defunct Fawcett Comics as of

issue #86, it too made no mention of the centenary, just

as Dell's Gene Autry Comics #100 in June 1955.

It had now been over two years that any publisher cared

to acknowledge, let alone celebrate the centenary of a

title - but things were about to change. At least a

little. |

| |

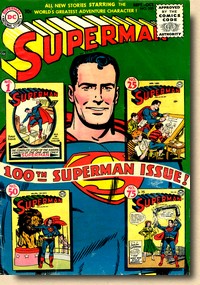

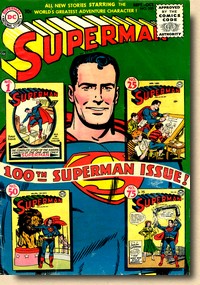

Superman #100

(DC, September 1955)

|

|

Detective Comics was

DC's flagship title, but the Man of Steel was

their real forerunner, and when Superman

#100 hit the newsagent stands in September 1955,

the long period of centenary silence was over as

the cover made it clear to potential buyers that

this was, indeed, the "100th SUPERMAN

ISSUE !". Sporting a Superman portrait

by Win Mortimer it also featured the covers of Superman

#1, 25, 50 and 75.

A nice

way to celebrate the title's centenary, the

contents of the issue, however, consisted of

three run-of-the-mill Superman stories which

could just as well have featured in the previous

or next issue. And as there was no editorial page

at all, the celebration remained restricted to

the cover of Superman #100.

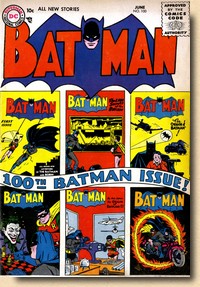

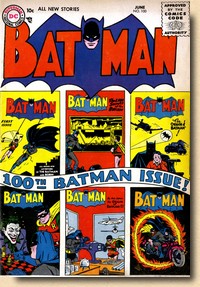

The

same would be true for Batman #100, the

next big centenary for DC, in June 1956. Almost

an exact copy of the Superman centenary design,

it sported the same banner plus sa collage

featuring the covers of Batman #1, #23,

#25, #47, #48 and #61, but no special or

celebratory content at all.

|

|

Batman

#100 Batman

#100

(DC, June 1956)

|

|

| |

| In between Superman

#100 and Batman #100, Dell had published Roy

Rogers and Trigger #100 (April 1956) and Quality

sent out Blackhawk #100 (May 1956) to the

newsstands, but both followed the established rule of

making no mention at all of the centenary - which was

also true for the first centenary issue of 1956, Harvey's

Dick Tracy #100. |

| |

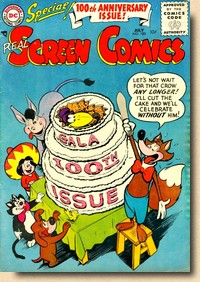

Real Screen Comics #100

(DC, July 1956)

|

|

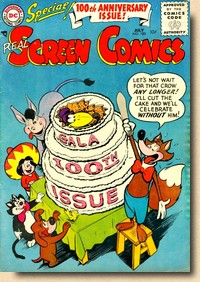

It was again DC who changed

that tune a bit - by going back to the centenial

issue celebration roots with another birthday

cake cover, this time for Real Screen Comics #100

in July 1956.

But

while the cover celebrated the "GALA 100TH ISSUE", the

actual contents made no mention of the occasion

whatsoever - which wasn't for lack of page space

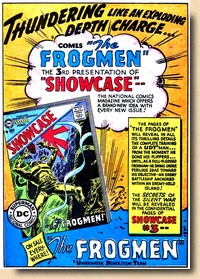

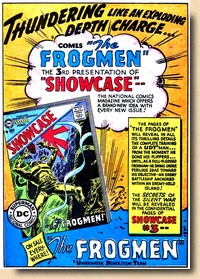

available for in-house use, as a full page ad for

DC's new Showcase title illustrated.

Rather, it was the same old routine of

"don't mention the centenary". It is

thus somewhat ironic that the ad for Showcase

pointed at something entirely new: Showcase

#4 (October 1956) would usher in the "Silver

Age" of comic books (1956-1970).

But

before that introduction of the new Flash and the

following revival of super-heroes, two more

Golden Age titles (both published by Dell)

reached the centenary issues count: Lone

Ranger #100 in October 1956 and Marge's

Little Lulu #100.

|

|

In-house ad from Real

Screen Comics #100 (DC, July 1956)

|

|

| |

| Neither of the two broke

with tradition, and hence didn't even mention the

occasion on the cover. During

the Golden Age of comic books, some 60+ titles reached an

issue number count of 100 between 1942 and 1956, but as

shown, only a mere handful pointed out the centenary to

readers with a blurb on the cover. Even fewer went as far

as to feature a special 100th issue cover (with birthday

cakes somewhat en vogue), and only one - Whiz

Comics #100 from August 1948 - actually featured a

special celebratory story.

Most publishers didn't even

blink, and while this all seems somewhat odd from the

marketing conscious perspective of the 1970s and onwards,

it was consistent with the way comic books were viewed at

the time both by the people who produced them and those

who read them. In the 1940s and 1950s comic books were

expendable reading with a collectible value to only a

very small group of fans. There was also very little to

no continuity at all between issues, other than the

central characters; it therefore didn't matter which

issue number a comic book carried. Editors also didn't

really bond with the readership, with the exception of

Fawcett in their Captain Marvel titles. The perception of

celebrating (and also cashing in on)

"anniversary" or "benchmark" issues

had yet to develop, even though Famous Funnies

#100 did hint at this in its editorial in October 1941.

The days of the

"long-awaited blockbuster spectacular collector's

item 100th issue" were yet to come, and they were

still quite far away in 1956.

|

| |

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY MILLER John Jackson

(2011) "Where Did Comics Numbering Come From?

A look at why comic books are numbered unlike most

American magazines",

Comichchron.com, 10 July 2011

STALEY

Oliver (2018) "Stan Lee and Marvel saved the

comic-book industry after the US Congress tried to kill

it", Quartz

Online, 17 November 2018

WRIGHT

Bradford W. (2001) Comic Book Nation: The

Transformation of Youth Culture in America,

Johns Hopkins

|

| |

|

The illustrations presented here are

copyright material.

Their reproduction for the review and research purposes

of this website is considered fair use

as set out by the Copyright Act of 1976, 17

U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2020

uploaded to the web 9 February 2020

|

| |

|