|

|

A

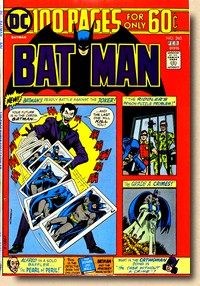

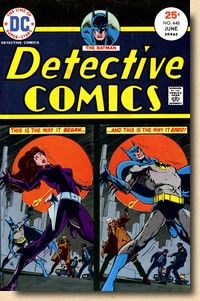

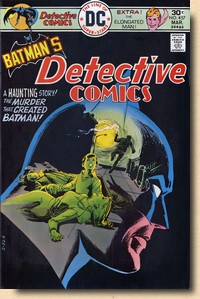

HAZY SHADE OF BATMAN

AN OVERVIEW OF DC's COLLECTED

EDITIONS OF

BATMAN MATERIAL FROM THE BRONZE AGE (1970-1983)

|

| |

| |

| |

A BRIEF HISTORY OF COLLECTED

EDITIONS

|

| |

| In 1986, DC Comics

published a 336 pages strong and oversize (6.8" x

10.2") anthology paperback titled Superman: The

Greatest Stories Ever Told. Selected by "a

special committee at DC", it contained 18 stories

spanning the years from 1940 to 1986 and was intended to

coincide with the Man of Steel's 50th anniversary. It was a publication format pioneered

back in 1974 by Marvel Comics and their smash hit Origins

of Marvel Comics in collaboration with Simon &

Schuster. Subsequently followed by many themed Marvel

anthologies throughout the 1970s and early 1980s (e.g. Bring

On The Bad Guys, 1976), there was nothing comparable

from DC until that 1986 Superman stories collection.

|

| |

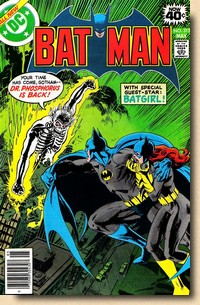

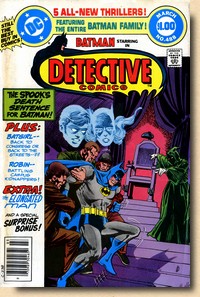

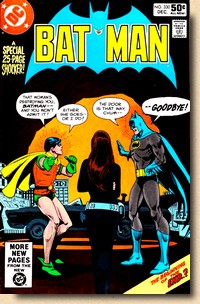

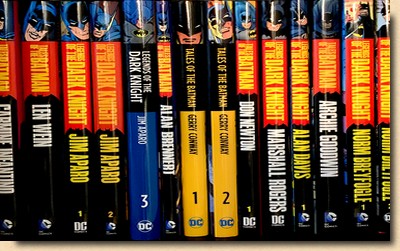

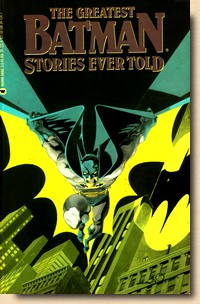

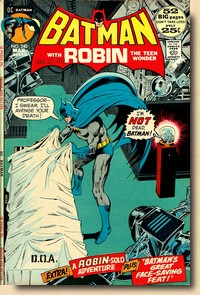

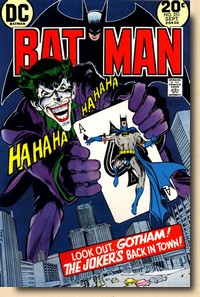

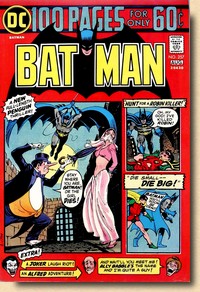

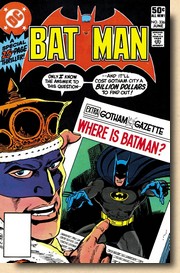

The Greatest

Batman Stories Ever Told (1989)

|

|

The

Superman collection was followed three

years later, in 1989, by an identical

anthology in order to celebrate Batman's

50 years in publication: The Greatest

Batman Stories Ever Told, published

by Warner Books, collected mutiple

stories from 1940 to 1981 on 343 pages.

It was a nice, if somewhat fanciful

collection of Batman stories which, for

the largest part, had not been accessible

to the vast majority of readers and fans

for a while. As such, the trade paperback

collecting reprints was a welcome

treasure trove. But even as DC was

putting out its Superman and Batman

anthologies, Marvel had already

successfully tried out a new reprint

formula: launched in 1986, the Marvel

Masterworks also focused on one

specific superhero (or group of

superheroes) but - rather than being

anthology collections - reprinted their

material in chronological order of

publication, starting out at the very

beginning.

Marvel put

the Mastwerworks series on hold

in 1994, and before continuing them in

1997 (and publishing them to this day),

introduced their Essential Marvel

series in 1996.

|

|

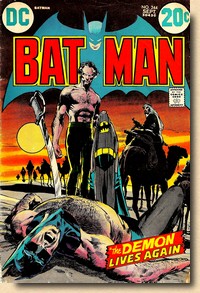

The Greatest

Batman Stories Ever Told (1989)

|

|

|

| |

| Unlike the Masterworks,

which were (and still are) hardcover books printed in

full colour on heavy glossy paper, the Essentials

reprinted classic material in black & white on paper

which was highly reminiscent of the cheap newsprint used

in the 1960s and 1970s. Each volume contained around

20-30 issues of a classic Marvel title in sequential

order, running up to a staggering pagecount of between

450 and 650 pages. |

| |

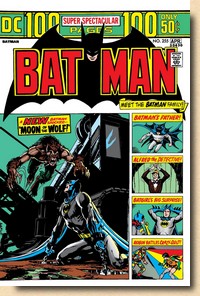

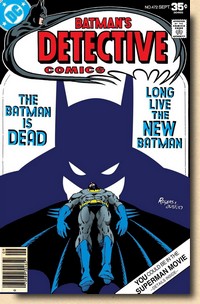

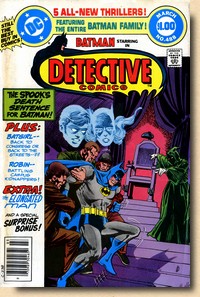

Showcase Presents

Batman #6 (2016)

|

|

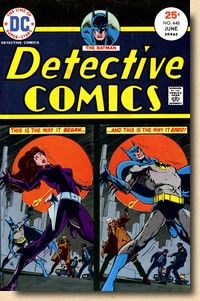

Back in 1989, DC had

launched its own version of the

Masterworks concept, calling the series

the DC Archive. Reprinting early

material in (mostly) chronological order,

the Batman got his first volume in 1990,

starting out with his very first

adventures from Detective Comics.

The series was cancelled in 2014, with Batman

Archives #8 being the last

Darknight-themed volume (published in

2012) and only just making it into the

1950s regarding the material reprinted. More ground was

covered in DC's Showcase format,

which followed the formula set out by

Marvel's Essential line and

introduced in 2005. The Batman material

reprinted here in black & white (both

from Detective Comics and Batman)

reached the year 1972 with its sixth

volume in 2016, but it appears that DC

has since discontinued the Showcase

format.

The

point to take away from this little

snippet of comic book reprint publication

history: while Marvel has always been

good at this game, DC has more than once

presented itself as truly struggling with

the task - witness, for example, the by

now third attempt to reprint the Golden

Age (1940s and 1950s) Batman material,

first in the hardcover Archives

series (aborted), then the trade

paperpack Chronicles (aborted),

and now the oversize Omnibus series

(ongoing and into the early mid-1950s,

with volume 9 announced for December

2020).

|

|

|

| |

| For the Darknight

Detective's 80th publication anniversary in 2019, DC's

official publication was yet another anthology

collection: Detective Comics: 80 Years of Batman.

But looking sideways at Marvel's ever-expanding Masterworks

collection, one might wonder how DC has made the classic

Batman Bronze Age period (ranging from 1970 to 1983)

accessible to fans and readers. What follows is the long

and detailed answer, but the short reply would have to

be: DC Comics (still) has no idea how to properly reprint

their classic material, leaving fans with a plethora of

collected series and lots of duplicates while still

having to face missing issues and stories. And: there is

a reason why Marvel excels and DC sucks at reprints. |

| |

| |

DC's

ILLOGICAL ANTHOLOGICAL APPROACH TO COLLECTED

EDITIONS

|

| |

|

| While Marvel Comics (and

other comic book publishers) have fully realized what

their fans and readers really want when it comes down to

reprints - namely to be able to (re-)read a certain

series or a certain hero's adventures in the

chronological order in which they originally appeared -

DC Comics has stubbornly stuck to the anthology format. An anthology is a collection

of (chiefly literary) works chosen by the compiler; the

term traces its origin back to a Classic Greek word

literally meaning "a collection of blossoms".

While this works fine under certain circumstances, a

series of anthologies from a large trove of material

(such as Batman's comic book adventures) will inevitably

produce both duplicates and gaps at the same time: some

"blossoms" will be reprinted time and time

again, while other material will never be selected. For

extensive reprints, it becomes a highly illogical

approach and burdens the reader in more ways than one.

DC Comics initially put out

a fine anthology series centering on specific decades of

Batman stories in the late 1990s and early 2000s, of

which Batman in the Seventies and Batman in

the Eighties cover a nice selection of Bronze Age

material. But when the time came to reprint Batman's

adventures from that period, as featured in Batman

and Detective Comics, in a more comprehensive

way, DC made the awful decision to organize their Batman

collections by creative talent rather than by narrative

continuity.

|

| |

Batman

in the Seventies (2000)

|

|

Batman

in the Seventies (2000)

|

|

Batman

in the Eighties (2004)

|

|

Batman

in the Eighties (2004)

|

|

|

|

| |

| The fundamerntal

shortcoming of this approach is the indifference and lack

of understanding on the part of the publisher that

writers and/or artists frequently changed. The resulting

anthology will therefore only feature the work involving

a certain spotlighted creative talent (e.g. writer A or

artist B), and while that work will be presented in order

of publication, such a reprint volume will not feature an

uninterrupted sequence of issues because writer A or

artist B may have worked on issues #22 and #24 but not

issue #23. This is no problem for stories which are told

and concluded in one issue, but Batman was one of the

first characters where DC followed Marvel's lead with

regard to continuity and on-going plots, which happened

occasionally as of the early 1970s and then extensively

in the early 1980s. The

following overview by year shows the resulting gaps as

well as duplicates and triplicates of DC's anthological

approach, and also illustrates how following storylines

very often involves having to switch from one collected

edition to another.

|

| |

1969

|

| |

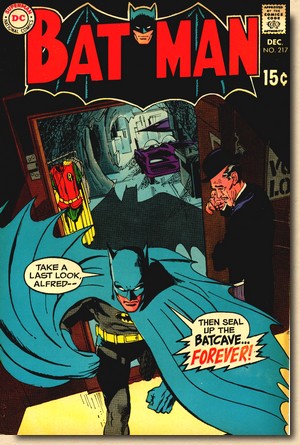

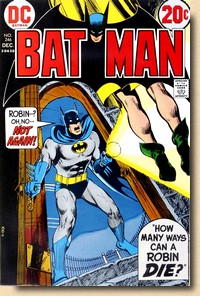

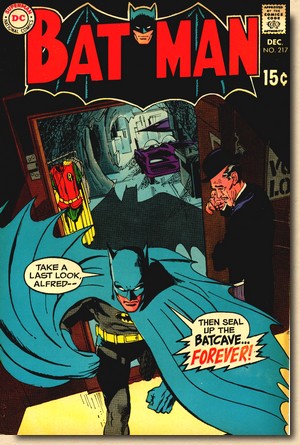

| Batman #217

(December 1969, on sale 21 October 1969), written by

Frank Robbins, pencilled by Irv Novick, and sporting a

Neal Adams cover, kicks off the comic book Bronze Age for

Batman, a period characterized by the disbanding of the

Batman & Robin team as Dick Grayson goes to college

and Bruce and Alfred move from Wayne Manor on the

outskirts of town to the Wayne Foundation in Downtown

Gotham. |

| |

Batman #217

(December 1969)

|

|

It was a drastic move even by

comic book standards. After all, the Batcave had

become a set piece in the perception of Batman as

a popular culture icon, not the least cemented

into place by the frequent views offered to the

millions of people watching the 1960s cult

television series - and the trademark call of "Robin,

to the Batcave!" But then

maybe that was precisley what writer Frank

Robbins had in mind at the time.

"Batmania" was over for good, and by

the end of the 1960s a number of talents at DC

comics had to almost reinvent the Darknight

Detective from scratch in order to pull the

character from the debris of the "camp"

era when the comic books followed the TV series

as closely as they could in order to cash in on

the popularity - which they did, at least for a

while. When the TV show ended, so did the good

times for the Dynamic Duo in their original

medium.

From

this point on,

Batman stories generally start to have a more

"serious" tone, often linked to a “back

to the (darker) roots” transition, leaving

behind the camp humour and sci-fi silliness of

the 1960s for good - and the Batcave

would not be opened up again until Gerry Conway

handed Bruce Wayne and Alfred (and Dick) back the

keys in Batman #348 (June 1982), which

made for an incredible 131 issues (and twelve and

a half years in real time) without the original

Batcave.

This starting point,

Batman #217, was reprinted in 1999 in the

collected edition Batman in the Sixties.

Although out of print, both new and second hand

copies can still be found without major problems;

Batman in the Sixties is also available in

digital form.

|

|

| |

| |

1970

|

|

| |

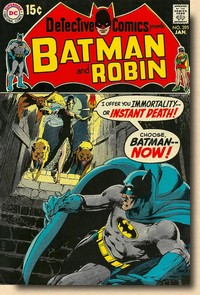

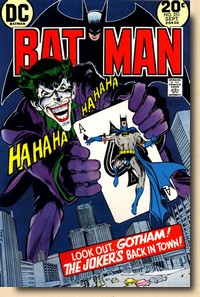

| DC’s flagship title is

published monthly throughout 1970, whereas Batman

skips the months of April and October, resulting in 10

issues that year (of which two are “Giant Size”

all-reprint issues with 1950s material). It is here that

Dennis O'Neil's starts his iconic run on Batman together

with Neal Adams in Detective Comics #395

(January 1970, on sale 26 November 1969). O'Neil's was looking to make the world of

superheroes feel closer to the real world, moving

characters from spanky clean and sunny surroundings with

intermittent but passing super villain threats to a world

of gritty street level problems which wouldn't go away

even after the super villain was down. O'Neil modernised

Wonder Woman and Green Arrow that way, but when it came

to the Batman, his approach was a markedly different one:

It wasn't so much about updating but rather about

restoration, about peeling off layer upon layer of

primary-colour gloss which had been slapped onto the

character in 30+ years, until the original work of art

became visible again.

Taking up a

cue from writer Bob Haney and artist Neal Adams who had

portrayed Batman in a very sombre way in Brave and the

Bold #79 (August/September 1968) - and which was

quite unlike the regular stories in Batman and Detective

Stories - Denny O'Neil undertook a deliberate effort

to move the Darknight Detective away from the completely

worn out campy vein of the TV series (which ended in

1968) and to once again return the character to his

darker and grittier roots as a mysterious night-time

vigilante:

|

| |

|

|

"I

went to the DC library and read some of the

early stories. I tried to get a sense of what

Kane and Finger were after."

(O'Neil in: Pearson & Uricchio 1991)

This

take on the Batman by Dennis O'Neil was perfectly

reflected by the artwork of Neil Adams, and it

would resound for decades and leave an indelible

mark not only on the character but indeed comic

book history.

"We

went back to a grimmer, darker Batman, and I

think that's why these stories did so well

(...) Even today we're still using Neal's

Batman with the long flowing cape and the

pointy ears." (Giordano in:

Daniels, 1999)

Maybe that's why

only Batman stories from 1970 which were drawn by

Neal Adams have been reprinted in collected

editions so far (not surprisingly, Batman

Illustrated by Neal Adams #2, published in

2004, contains all of them).

|

|

| |

| The result of an approach

which reprints issues according to creative talent (in

this case Neal Adams) in an anthology format can clearly

be seen: no less than 14 of the year's total of 20 issues

of Batman and Detective Comics (not

counting the reprint Giant Size issues) have not been

reprinted by DC so far. |

| |

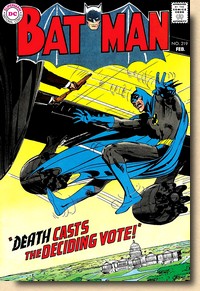

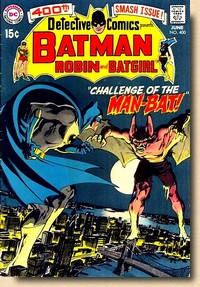

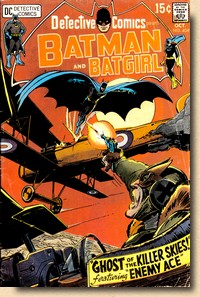

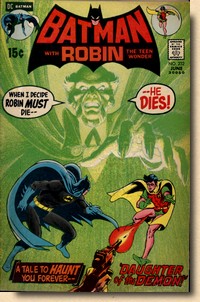

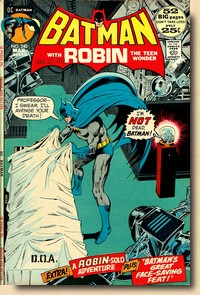

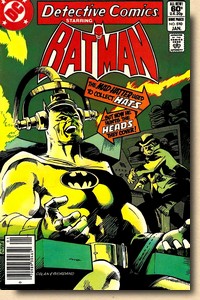

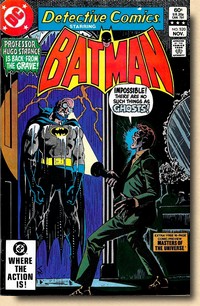

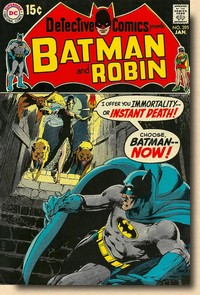

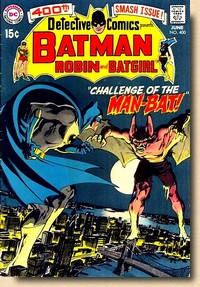

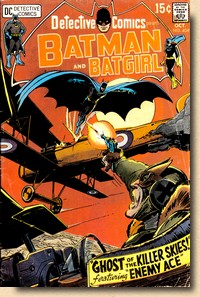

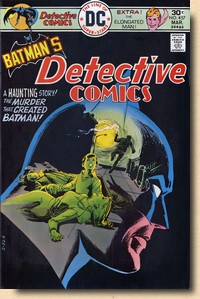

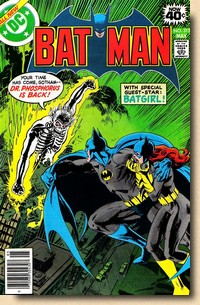

Detective

Comics #395

|

|

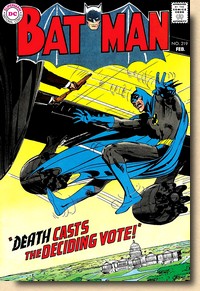

Batman

#219

|

|

Detective

Comics #400

|

|

Detective

Comics #404

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1971

|

|

| |

|

|

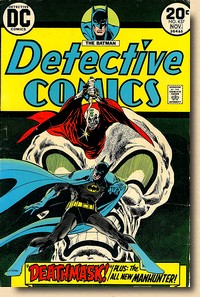

Detective

Comics is published monthly throughout 1971,

whereas Batman skips the months of April

and October, resulting in 10 issues that year (of

which two are “Giant Size” all-reprint issues

featuring material from the 1950s). Again, as with the previous

year, the reprinted material from 1971 to this

date only includes Batman stories drawn by Neal

Adams - all of which are featured in Batman

Illustrated by Neal Adams #2.

And another result

of the anthology approach becomes apparent here

as well: the “cumulative reprinting” of

certain key issues, illustrated by the

introduction of Ra’s al Ghul in Batman

#232 and a pivotal Two Face appearance in Batman

#234, both of which are reprinted in no less than

four different collected editions each.

So while 1971 Batman

material has been reprinted in no less than 10

different collected editions between 1989 and

2020, there still is a total of 14 (not counting

the reprint Giant Sizes) issues of Detective

Comics and Batman from 1971 which

are not accessible through collected editions to

this day.

|

|

| |

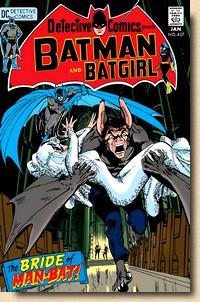

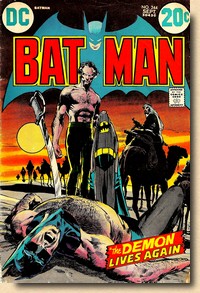

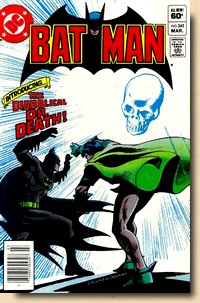

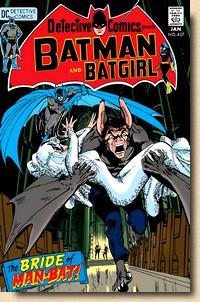

Detective

Comics #407

|

|

Detective

Comics #408

|

|

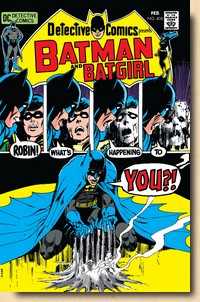

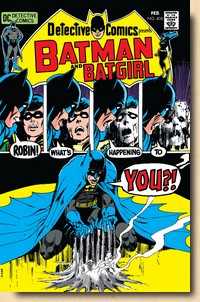

Batman

#232

|

|

Batman

#237

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1972

|

|

| |

|

|

Detective

Comics is published monthly throughout 1972,

whereas Batman changes its publication

schedule in mid-year and now skips a total of

four months, namely January, March, July and

November. For the year 1972, however, this still

results in a total of 10 issues of Batman. This is the first year of

Batman’s Bronze Age period which has material

reprinted in collected editions which did not

involve the artwork of Neal Adams.

While this does

reflect a broader approach with regard to

creative talent (certainly a good thing for

fans), it does, however, also clearly show the

shape of complications to come - which is

reflected in the fact that no less than four

different collected editions are needed to access

the seven reprints from 1972.

This contrasts

sharply with the fact that no less than 12 (not

counting the one Giant Size) issues of Detective

Comics and Batman from 1972 have

not been reprinted to this day.

|

|

| |

| And again, the “cumulative

reprinting” which is so typical of multiple anthologies

on one subject, is in evidence, with Batman #243

and #244 reprinted in no less than three different

collected editions. |

| |

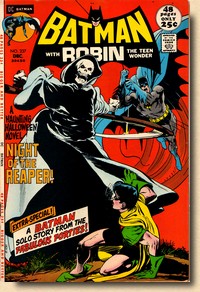

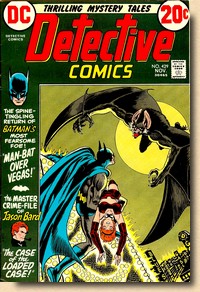

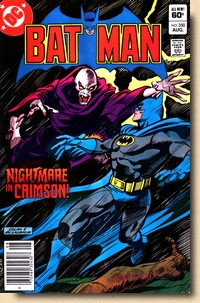

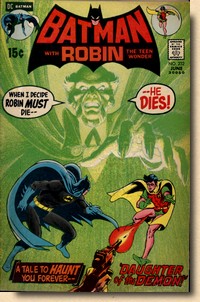

Batman

#240

|

|

Batman

#244

|

|

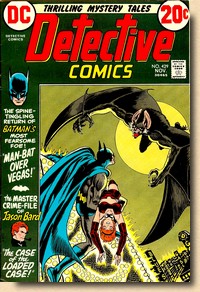

Detective

Comics #429

|

|

Batman

#246

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1973

|

|

| |

|

|

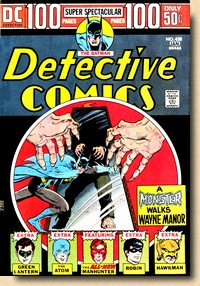

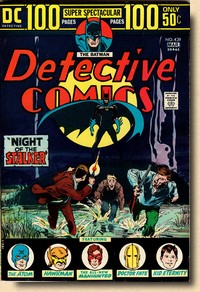

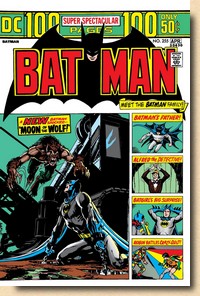

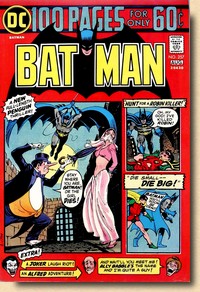

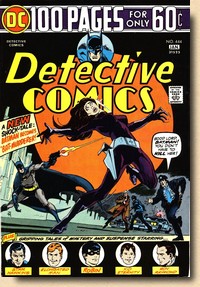

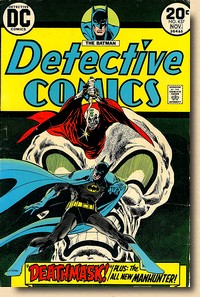

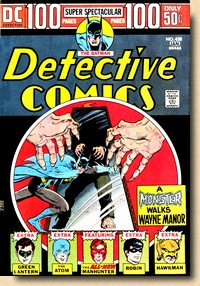

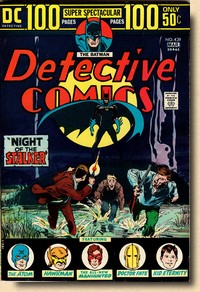

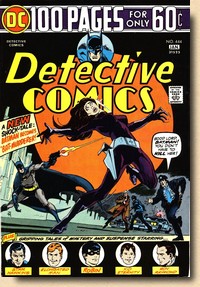

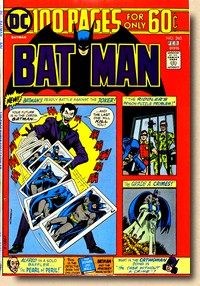

Detective

Comics is published monthly up until the

April 1973 issue, then skips a month and

continues as a bi-monthly title, resulting in a

total of 9 issues in 1973; as of the

December/January 1973/74 issue, Detective

Comics also changes to the 100 pages

"Super Spectacular" format (adding lots

of non-Batman material, some of it reprints). Batman is published

monthly with the exception of January, March,

July and November, resulting in a total of 8

issues of Batman in 1973.

The chart for 1973

really says it all - and paints a clear picture

of the incongruity of DC's approach to Brone Age

reprints. While there are no less than 6

different collected editions (published between

1989 and 2017) featuring material from 1973, only

a mere three issues have actually ever been

reprinted - and to read them you will need at

least two different collected editions. Which

also means that two of these issues have been

reprinted three times and one of them twice - and

that fans and collectors are more than likely to

end up with the same reprinted issue in more than

one collected edition on their bookshelf.

All in all, one

might be hard pressed to find a better example

than the year 1973 to illustrate, in a nutshell,

the absurdity of the anthological approach to

Batman reprints.

|

|

| |

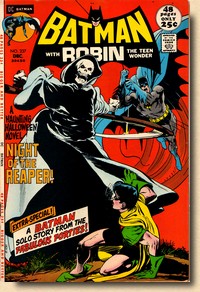

Batman

#251

|

|

Detective

Comics #437

|

|

Batman

#240

|

|

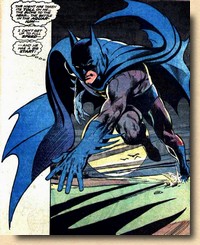

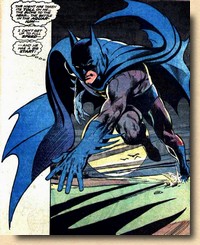

Iconic

Batman posture by Neal Adams from

Batman #251 - one of

only three titles from DC's 1973

slim reprint pickings

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1974

|

|

| |

|

|

Detective

Comics is published bi-monthly throughout

1974, as is Batman. As the annual number of

issues decreases to a total of 12, the percentage

of those reprinted in collected editions goes up

to two thirds. However, no less than 5 collected

editions are required in order to read those 8

reprinted Batman features; it starts to get

complicated, and DC’s lack of coherence in its

reprint policy is begining to ask a lot from

fans.

In order to read the

reprinted material in chronological order, one

first needs to turn to Batman: The Greatest

Stories Ever Told #1 (2005) for one issue,

then switch to either Tales of the Batman:

Len Wein (2014) or Batman Illustrated by

Neal Adams #3 (2006) for another issue,

before switching to Tales of the Batman:

Archie Goodwin (2013) - at least this

collected edition provides two consecutive issues

(Detective Comics #440 and #441). After

that, yet another different volume needs to come

down from the bookshelf: The Greatest Batman

Stories Ever Told #2 is from 1992

and a sequel to the first collected edition from

1989, not the confusingly similarly titled Batman:

The Greatest Stories Ever Told #1 from 2005.

|

|

| |

| Confusingly similar titles

are, however, the least of worries for anyone wishing to

read the 1974 reprints in chronological order, because The

Greatest Batman Stories Ever Told #2 (1992)

only offers one issue. For the next one - Detective

Comics #442 - there are no less than 4 different

collected editions to chose from, although sticking with Tales

of the Batman: Archie Goodwin (2013) is the best

option as this volume also reprints the next issue: Detective

Comics #443. For Detective Comics #444,

however, yet another switch is necessary - most likely to

Tales of the Batman: Len Wein (2014) which was

already in play earlier, although it is also reprinted in

Legends of the Dark Knight: Jim Aparo #3 (2017). Again, the absurdity of the

anthological approach pursued by DC for the Bronze Age

Batman material becomes painfully evident - painful also

because although the reprinted material is far from

complete one needs to acquire at least 5 separate

collected editions in order to be able to read those 8

reprinted main Batman features.

|

| |

Detective

Comics #439

|

|

Batman

#255

|

|

Batman

#257

|

|

Detective

Comics #444

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1975

|

|

| |

| Detective Comics

and Batman are both published bi-monthly until

the April 1975 cover date, at which point both titles

revert to a monthly publication schedule (Batman

#261 is cover dated March/April, Batman #262

carries a cover date of April). This change is

accompanied by reverting both titles from their 68-page

“Giant” format back to regular comic book format as

of Batman #263 and Detective Comics

#446 (which also spells the end for reprints of short

Batman stories from both titles from the 1940s, 1950s and

1960s in order to fill those 100 pages). |

| |

|

|

Of the

total 21 issues across both titles, however, a

mere 6 have been reprinted in collected editions

by mid-2019, a fact once again entirely due to DC’s

decision to organize their Batman collections by

creative talent rather than by narrative

continuity: Whilst writer Len Wein and artist Jim

Aparo are covered, most Batman features in both

titles during 1975 were penned and pencilled by

others (most notably writer David Vern and

artists Ernie Chan), but as their work has not

(yet) been collected, fans wanting to read up on

those talents’ lengthy runs will need to turn

to the original comic books. DC has announced a

collected edition with Batman work by José Luis

García-López for late 2020, which then might

reprint Detective Comics #454.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Batman #260

|

|

Detective Comics #448

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1976

|

|

| |

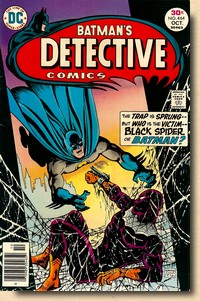

| Detective Comics

and Batman are both published monthly throughout

1976, but although this was a year of fun issues with

many done-in-one and some done-in-two storylines (as well

as being the year when barcodes starting appearing on

covers and Detective Comics went through no less

than two title logo changes), 1976 is at the current

moment (2020) almost non-existent in DC’s collected

editions. |

| |

|

|

Once

again, this is entirely due to the fact that DC

structures and organizes its reprints, for the

most part, by artist rather than by narrative

continuity, although Detective Comics

#457 (reprinted in no less than three different

collected editions) with its classic Dennis O’Neil

story “There is no Hope in Crime Alley!”,

penciled by Dick Giordano, doesn't fit that

formula - neither O'Neil nor Giordano have had

their Batman work featured in an anthology volume

so far. Only

three other issues of Detective Comics from

1976 have been reprinted to this date (with no Batman

issue at all), making this possibly one of the

most frustrating years for Bronze Age Batman

fans, even more so than 1975. It is this period

in the publication history of Batman which really

shows how badly DC is handling its collected

editions and reprint material.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Detective Comics #457

|

|

Detective Comics #464

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1977

|

|

| |

| Batman is

published monthly, while Detective Comics goes

back to a publication schedule of being bi-monthly until

the May 1977 cover date when the publication schedule is

changed to 8 issues a year, i.e. “monthly with the

exception of January, April, July and October” (as

labelled by DC). Of

the total 20 issues of Batman and Detective

Comics published in 1977, 11 have been reprinted.

Some only feature in one collected edition (e.g. Detective

Comics #468 or Batman #293) while others,

once again, have been almost reprinted to death. Case in

point for 1977 is Detective Comics #474, the

second appearance of Deadshot (after he previously

appeared in Batman #59, June-July 1950) and

published in no less than 5 reprint collections between

1988 and 2019.

|

| |

|

|

DC’s

policy of organizing collected editions by artist

rather than by narrative continuity provides an

especially irksome situation where the Batman

feature of Detective Comics

#468 is

reprinted in Legends of the Dark Knight:

Marshall Rogers (2011) but without its cover

– which was drawn by Jim Aparo and is hence

reprinted, on its own, in Legends of the Dark

Knight: Jim Aparo #3 (2017). It hardly gets any worse, but

unfortunately this is not the only example of an

editorial policy which does not only not care for

continuity or integrity of the material

reprinted, but simply doesn't seem to care at

all; there's no less than 30 issues of Batman

not reprinted between issues #260 (original

cover date January 1975) and #291 (September

1977) to date.

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

Detective Comics #472

|

|

Batman #294

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

1978

|

|

| |

| Batman is still

published monthly, while Detective Comics starts

out as monthly with the exception of January, April, July

and October (i.e. eight issues a year) but then reverts

to bi-monthly as of Detective Comics #476

(March/April cover date). |

| |

|

|

At this

point, things get even more complicated: The main

Batman feature (17 pages) of Batman #303

is not collected, but the “Unsolved Cases of

the Batman” back-up feature (8 pages) is (in

the 2019 Legends of the Dark Knight: Michael

Golden). The table shown here, however, only

lists collected main features of the two Batman

titles, and for 1978 there are no less than 13 -

yes, thirteen - collected editions. This is due

to the by now all too familiar phenomenon of a

few issues being reprinted multiple times, such

as Detective Comics issues #475 and

#476, which are reprinted in no less than 6 -

yes, six - different collected editions.

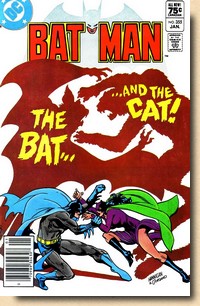

Detective Comics #475

/ Batman #305

|

|

| |

| |

1979

|

|

| |

| 1979 is the first year for

which DC’s collected editions provide a comprehensive

and almost entirely complete reprinting – and most of

it in just two volumes, thanks to a stable roster of

writers and artists. |

| |

|

|

While Batman

is still published monthly, Detective Comics

continues to be published bi-monthly but, because

it is merged with the previously ongoing Batman

Family title, becomes a “Dollar Comic”

with 68 pages as of issue #481. Due to this

merging of titles, the cover dates become a bit

confusing; even though Detective Comics

#480 had a “November/December 1978” cover

date, the new "Dollar Comics" Detective

Comics #481 has a “December/January 1979”

cover date. The

Batman run is almost complete (missing

only issue #311) in Tales of the Batman: Len

Wein (2014), while Detective Comics

#483 through 487 are all reprinted in Legends

of the Dark Knight: Marshall Rogers (2011),

missing only the first two issues of 1979 (both

of which are featured in two other collected

editions).

|

|

The

one that (almost) got away from DC's 1979

collected editions: Batman #311,

written by Steve Englehart and pencilled

by Irv Novick with inks by Frank

McLaughlin. It will be featured

in a new collected edition, Tales of

the Batman: Steve Englehart,

announced by DC for publication in 2020.

|

|

|

| |

| |

1980

|

|

| |

| 1980, just as the previous

year, has a comparatively good coverage: of the 22 total

issues of Batman and Detective Comics,

only three have not been reprinted to this date. |

| |

|

|

Batman

is still published monthly, whereas Detective

Comics continues to be published bi-monthly

up until the April 1980 cover date issue, from

which point on it too regains its monthly

publication status, while retaining its “Dollar

Comic” format with 68 pages until the November

1980 issue when the format reverts back to the

standard 36 page count. Once again, however, the

proliferation of collected editions is

staggering, with no less than eleven publications

(ranging from 1989 to 2020) featuring reprints

from 1980. Luckily for the fan, Tales of the

Batman: Don Newton (2011) includes almost

all issues of Detective Comics, while

most of the Batman issues can be found

in Tales of the Batman: Len Wein (2014),

complemented by reprints featured in Tales of

the Batman: Marv Wolfman #1 (2020).

Detective Comics #488

|

|

Batman #330

|

|

|

| |

| |

1981

|

|

| |

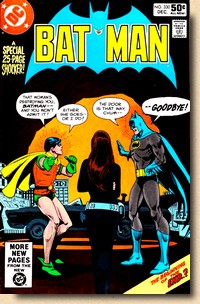

| Both Batman and Detective

Comics are published monthly throughout 1981, and it

is the third year in a row enjoying almost complete

coverage in DC's various collected editions, with only

one single issue missing (Batman #336). |

| |

|

|

However,

the material from a total of 23 issues of Detective

Comics and Batman is scattered

throughout no less than 13 collected editions

published between 1988 and 2020, and the results

of this haphazard approach to structuring reprint

material is illustrated in an exemplary way by Detective

Comics #500. That anniversary issue

contains, amongst other features, two main Batman

stories, but while “To kill a Legend” is

reprinted in no less than 5 collected editions (Greatest

Batman Stories Ever Told, 1988; Batman

in the Eighties, 2004; Tales of the

Batman: Alan Brennert, 2016; Detective

Comics: 80 Years of Batman, 2019; Detective

Comics: Batman 80th Anniversary Giant,

2019), “What happens when a Batman dies?” is

reprinted only in one (Tales of the Batman:

Carmine Infantino (2014).

Three collected

editions provide the bulk of the 1981 material,

but a minimum of four separate collections is

required for continuous reading.

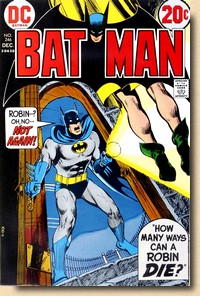

Batman #336 Batman #336

|

|

The

one that got away from DC's 1981

collected editions: Batman #336,

plotted by Bob Rozakis, written by Roy

Thomas and pencilled by José Luis

García-López (with inks by Frank

McLaughlin). DC has announced a

collected edition with Batman work by

José Luis García-López for late 2020

which is also to include Batman

#336.

|

|

|

| |

| |

1982

|

|

| |

| Both Batman and Detective

Comics are published monthly throughout 1982, and

that year serves as yet another excellent example to

illustrate the shortcomings of DC’s approach to

collected editions. |

| |

Initially

focusing on artist rather than writers,

the Tales of the Batman

collected editions contained numerous

ruptures of continuous storylines because

even though Gerry Conway wrote almost all

1982 issues of Batman and Detective

Comics, artists Gene Colan and Don

Newton took turns to cover the workload

of both titles (which carried a storyline

which continued over between the two

titles almost all throughout 1982).

"This

type of collection, organized by

artist rather than by narrative

continuity, makes for occasionally

frustrating reading, despite the

pleasures of the individual issues.

There are issues of Batman and

Detective Comics not present here

(i.e. not penciled by Colan) that

flesh out the vampire arc. As

presented here, it is full of holes,

and the conclusion is sudden."

(Burchby, 2011)

|

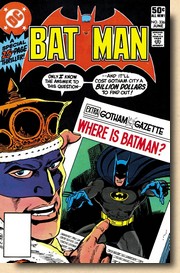

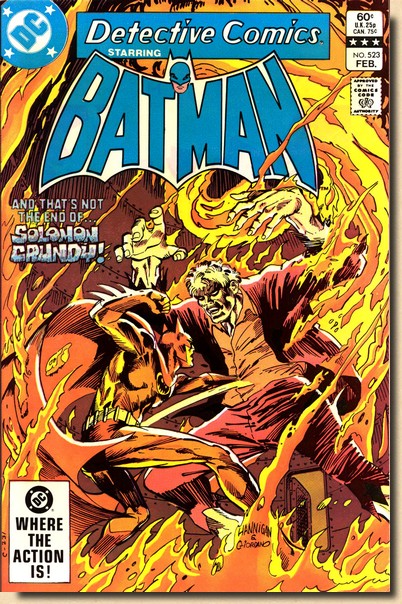

|

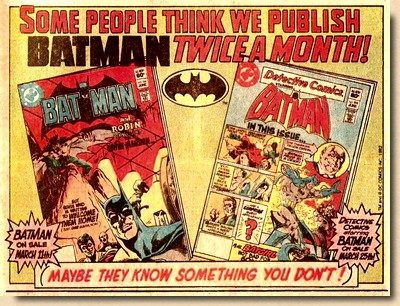

In-house ad from Detective

Comics #515

|

|

|

| |

| These are problems which

would never have occured had the issues been reprinted in

simple chronological order - and the situation was a

truly miserable affair until DC turned to featuring writers in

the Tales of the Batman collected editions; Tales

of the Batman: Gerry Conway #2 and #3 (published in

2018 and 2020) finally fixed the Batman year 1982 - except for Batman

#347. Don't hold your breath for a reprint of that

standalone story issue, though, as it was penned by

"guest writer" Robin Snyder and pencilled by

"guest artist" Trevor Von Eeden. Also noticeable -

once again - is the proliferation of reprint

publications: there's no less than ten, and two issues (Batman #348 and Batman #353) are

reprinted not twice, not thrice, but four times.

|

| |

|

| |

| |

1983

|

|

| |

|

|

Both Batman

and Detective Comics are published

monthly throughout 1983, the year commonly

defined as the last twelve months of the Bronze

Age period of comic books. The reprinted material from

1983 is a motley collection spread out over no

more than nine collected editions, yet still

leaves out one fifth of that year’s issues –

a problem which will not be cured until DC

publishes a volume of Doug Moench’s work, who

took over the scripting reigns from Gerry Conway

mid-year.

|

|

| |

|

| |

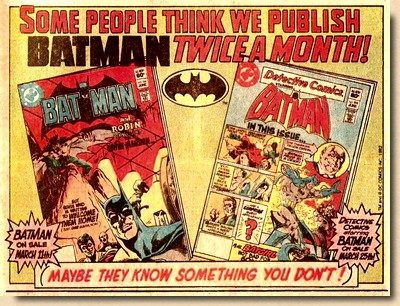

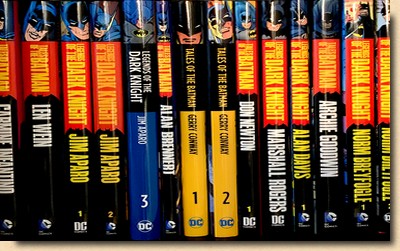

| When it comes to collected

editions of reprint material featuring the Batman

post-Golden Age (i.e. after 1956), DC Comics took a wrong

turn and just kept going. |

| |

|

|

A simple look at the

bookshelf of someone who owns a few of these

collected editions will already provide a first

hint, as just the backs of these hardcovers

display anything but coherence - quite unlike

rival Marvel (who of course excels at the game of

reprints), who managed to more or less maintain a

uniform look of their Masterworks over

the past twenty years. The problem

started when DC decided - after previously

structuring reprints by a theme, such as

"Batman in the Seventies" or stories

featuring a specific villain - to publish

collected editions which focused on artists.

What, one wonders,

was DC thinking? That readers would enjoy the

artwork so much that they wouldn't really care

about the story?

|

|

| |

| Clearly,

collected editions focused on artists are inherently flawed, as pencillers

working continuously on a specific title were not the

norm at DC during the Bronze Age (and neither were they

over at Marvel, with a few exceptions, such as Gene

Colan's run on the entire 70 issues of Tomb of Dracula). So while e.g. the two volumes of

Colan's Batman artwork from 1981-1983 are nice, they

present the reader with far too many gaps and holes in

ongoing stories to be truly enjoyable. They are,

essentially, useless, and once DC started to publish the

Batman Bronze Age material structured by writers, they

became obsolete. The switch to author-based collected

editions has improved things greatly for the second half

of the Bronze Age, but especially the early 1970s remain

in a sad state, with quite a few good Batman stories

waiting to be told again. It is unlikely that DC will ever

backtrack and start a Bronze Age reprint collection of

Batman material in chronological order (as they have done

with the Brave and the Bold material) - and if

they did, many fans would be faced with the decision of

whether or not to buy material they already own,

scattered across a plethora of volumes of collected

editions (as with the Brave and the Bold

material).

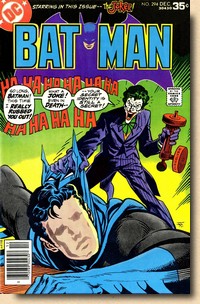

It's almost as though the

Joker is running the reprints editorial board straight

out of Arkham - and the joke is squarely on the readers,

the collectors, the fans.

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY BURCHBY Casey (2011) "Review: Tales of the Batman – Gene

Colan, Volume One",

in The Comics Journal, 28 October 2011

DANIELS Les

(1999) Batman: The Complete History, Chronicle

Books

PEARSON

Roberta E. & William Uricchio (1991) "Notes from

the Batcave: An Interview with Dennis O'Neil", in The

Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a

Superhero and His Media, Routledge

|

| |

| |

BATMAN

and all related elements are the property of DC Comics,

Inc. TM and © DC Comics, Inc., a subsidiary of Time

Warner Inc.

The illustrations presented here

are copyright material. Their reproduction for the

review and research purposes of this website is

considered fair use as set out by the Copyright Act

of 1976, 17 U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2020

uploaded to the web 1 June

2020

|

| |