|

|

| |

SPOTLIGHT

ON SPOTLIGHT

ON

THE

1973 DC COMICS REPRINT TITLES

AN

EPISODE OF THE "WAR OF THE SHELVES"

|

| |

|

| |

| In early 1967 the

almost unthinkable happened: Marvel overtook DC in sales

numbers and became the new number one of the industry -

only five years after DC themselves had snatched that

position from Dell (who had taken a terrible tumble due

to a misfired cover price policy). This was now indeed

the Marvel Age of Comics.

But while Stan Lee, in his

April 1968

Stan's Soapbox, declared "the

fatuous little feud we've been flaunting before the

public" to be officially over and that "from

this moment on, we'll no longer refer to our competition

as Brand Echh", there was still plenty of room

to consolidate and expand the number one position.

Ever since 1957,

Marvel had been severely restricted in terms of the

number of titles they could put out every month. Due to

the bankruptcy of its new distributor, Atlas/Marvel had

no choice but to

switch to Independent News, who were owned by National

Periodical - who also happened to own rival DC Comics.

The resulting contract limited Marvel to a monthly

publishing output of eight titles only (Cooke, 1998). But

that was all to change. By the beginning of 1968,

DC Comics and Independent News were

purchased by Kinney National Company - and since Marvel's

titles were selling better than DC's, any kind of

distribution cap was lifted. The result was instantly

visible as the title

count went up from 14 for January 1968 cover month to 20

by July 1968.

Ownership changes took place at

Marvel too. On July 1st 1968, the Wall Street Journal

announced the purchase of Martin Goodman's Magazine

Management Company (including Marvel Comics) by a

business conglomerate called Perfect Film & Chemical

Corporation, owned by Martin S. Ackerman (who was also

president of Curtis Publishing). But only a year later,

in mid-1969, Ackerman was ousted from Perfect Film's

board of managers (accused of diverting $6 million in

pension funds) and replaced by new CEO Sheldon Feinberg

in mid-1969, with the company being renamed Cadence

Industries in 1970. Goodman had never had a particular

interest in what he published (Hilgart, 2014), but he was

proud of being a publisher who sold well and was able to

read trends. Feinberg, the former CFO of Revlon, was the

first in a long series of top management at Marvel who

had never read a comic book in his life, had no previous

connection to publishing, and was in it for one reason

only: to make more money.

There was just one problem: comic

book sales were in a steady decline. As a consequence,

the only way to make more money was to make sure you got

a bigger slice of the shrinking market - and one way to

achieve that was to put out more titles. And since the

space at the sales point was not going to increase, you

could at the same time push the competition (which from

Marvel's perspective of superhero titles was primarily

DC) off the shelves.

Marvel was the comic book

industry's number one, but until mid-1972 DC still

published more titles - that is until Marvel launched the

"war of the shelves" through a proliferation of

titles.

"[Marvel]

did flood the market, but remember, this was that

period (...) where Marvel suddenly decided to put out

a whole bunch of books (...) trying to get market

share (...) lots of stuff came out in the '70s

because of this approach."

(Roy Thomas, in

Cooke 2001)

By the time DC realized what was

happening, it was already too late, even though Carmine

Infantino, DC's publisher since 1971, did try to stem the

tide in 1973 by emulating Marvel and putting out a few

new as well as some reprint titles in order to boost DC's

output and keep from getting pushed off of those shelves.

It was a valiant but ultimately ill conceived move which

only had a minimal and, above all, short lived effect. By

June 1974 Marvel's titles at the newsagents outnumbered

those put out by DC by leaps and bounds.

|

| |

This chart doesn't take into

account black & white magazine format publications

(of which Marvel put out a cartful too).

|

| |

| The new titles all broke new

ground for DC, but their success was underwhelming to say

the least. Shazam! kicked off in February 1973 and was, of course, DC

bringing Fawcett's Captain Marvel into the fold - but

since DC couldn't call him that any more (again, Marvel

had been swifter and more cunning) they came up with

Shazam. It was a title DC had a hard time letting go, but

poor sales sank it after 35 issues in May 1978. Prez,

featuring a teenage President of the US, was launched in

August 1973 and turned out to be a total failure which

only lasted for a mere four issues. Plop!

(another title with an exclamation mark), "the new

magazine of weird humor", fared somewhat better and

at least racked up a total of 24 issues between September

1973 and November 1976. If

the new titles weren't going to stop Marvel storming away

in the title number race, maybe reprint titles would.

Infantino had of course noticed that the House of Ideas

was not only launching new titles but also busy recycling

their 1960s superhero material along with 1950s horror

and sci-fi stories from the Atlas period. However, there

was a fundamental problem there: Marvel was really good

at reprints and had material (at least as far as

superheroes were concerned) which was "classic"

but less than ten years old - and which was actually in

demand. In comparison, DC had put out only a handful of

reprint issues since the early 1960s, and most of their

Golden and Silver Age material just wasn't hitting home

with current readers any more - after all there was a

reason why Dennis O'Neil and Neal Adams had to reinvent

Batman in 1969 to save him from cancellation.

But Carmine Infantino tried hard to

turn things around (as he had indeed done in the late

1960s), and with the blessings of the top brass at DC

(Sacks, 2014) he put out a number of reprint titles in

1973 to stem Marvel's tide. Needless to say the waves

just kept coming.

|

| |

|

| |

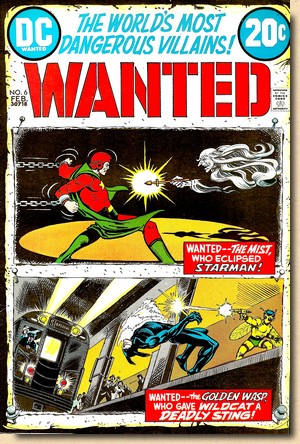

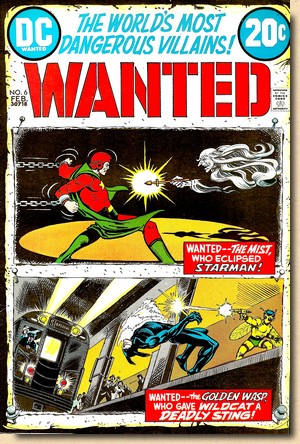

Wanted

#6

(February 1973)

|

|

WANTED

Launched -

August 1972

Cancelled - September 1973

Number of issues - 9

Strictly

speaking Wanted (sometimes also referred

to as Wanted, the World's Most Dangerous

Villains) was not part of DC's 1973 rush of

reprint titles, since it launched in August 1972.

The reason it is listed here is that five of its

total of nine issues were published in 1973, and

that it illustrates the problems DC had with its

reprint material in an exemplary way.

Wanted

was published monthly and based on an interesting

concept: Rather than spotlight the heroes, the

title featured their most notorious adversaries.

The problem was that most of the villains

showcased weren't exactly A-listers, and some of

them were downright obscure unless you happened

to be an expert on the DC superhero in question

(any takers for the Dummy, the Human Fly Bandits,

or Dr. Clever?).

DC could dig

deep into an extensive vault of previously

published material, and for Wanted they

even used material from comic books which at the

time of their original publication hadn't even

belonged to DC yet (such as Quality Comics'

somewhat unfortunately titled Doll Man).

The

fundamental problem (which few at DC seemed to

understand even in 1973) was that it wasn't just

the storytelling that was old and outdated, it

was the characters themselves.

|

|

| |

Compared to

Marvel's 1973 superhero reprint titles, which had titles

such as Marvel Super-Heroes (reprinting Hulk

stories from 1966), Marvel's Greatest Comics

(reprinting Fantastic Four material from 1966) or Marvel

Triple Action (repackaging Avengers stories from

1965) and all of which featured the new type of superhero

which had put Marvel at the top in the first place, DC

was trying to reheat twenty to thirty years old material

which compared even less favourably to Marvel now than it

had before.

The title was

discontinued after only nine issues.

|

| |

|

| |

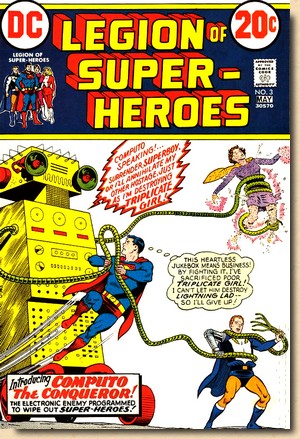

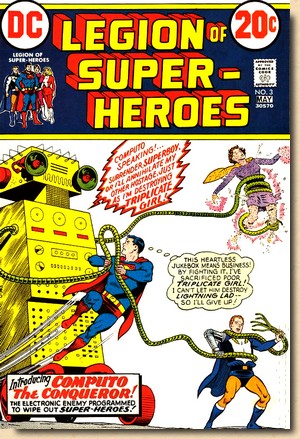

Legion of Super-Heroes #3

(May 1973)

|

|

LEGION

OF SUPER-HEROES

Launched -

February 1973

Cancelled - August 1973

Number of issues - 4

The first of

the 1973 reprint titles was Legion of

Super-Heroes, launched with a February 1973

cover date. Supplied with new covers by Nick

Cardy, it featured - no surprise, given its title

- material starring the Legion of Super-Heroes

which had previously been published between 1964

and 1966 in Adventure Comics (with

stories from Action Comics dating from

1957/58 added for the final two issues).

It switched

from monthly to bi-monthly publication after two

issues, before ceasing publication all together

after a mere four issues. While these were mostly

newer stories from less than ten years ago (and

therefore pretty much what Marvel was repackaging

in its superhero reprint titles), the already

mentioned problem was that these were 1960s

stories featuring heroes (such as Triplicate

Girl) and villains (such as Computo the

Conqueror) which had more of a 1950s feel to

them.

Now of course

DC could not reinvent itself through what had

already been published. However, material such as

this had been a contributing factor in Marvel's

success - the repetitive blandness of what Stan

Lee would increasingly enjoy calling "Brand

X" in the mid-1960s.

|

|

| |

| Considering these historical

facts, a reprint title such as Legion of Super-Heroes

with material from the mid-1960s was really not the best

idea. The majority of comic book readers must have felt

the same way, given the extraordinary short life-span of

this title. |

| |

|

| |

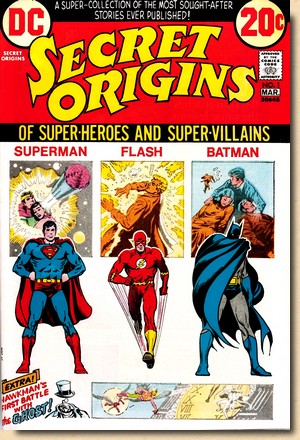

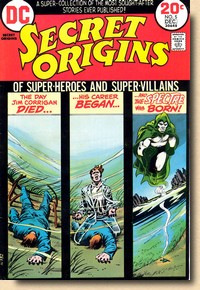

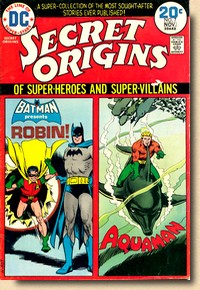

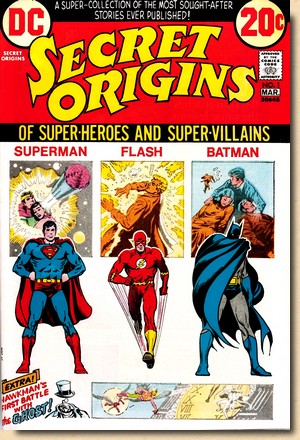

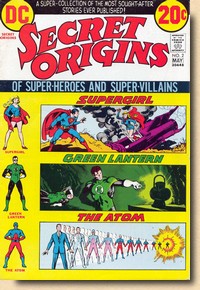

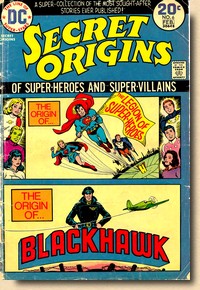

Secret Origins

#1

(March 1973)

|

|

SECRET

ORIGINS

Launched -

March 1973

Cancelled - November 1974

Number of issues - 7

Only one month

later, DC launched another superhero reprint

title, and Secret Origins - which

featured the origin stories of various DC heroes

(and villains) - was arguably the most

interesting of Infantino's 1973 reprint releases.

Strictly speaking, this was actually volume 2 of Secret

Origins, since DC had released a 84-pages

one-shot with the same title (and concept) back

in 1961, but the indicia of Secret Origins

#1 from March 1973 simply ignored that and stated

"Vol. 1 No. 1".

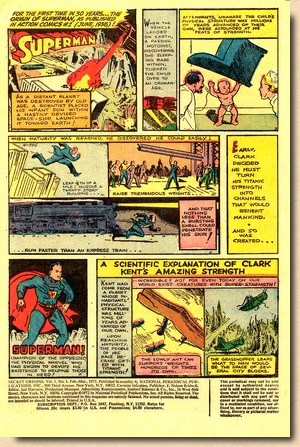

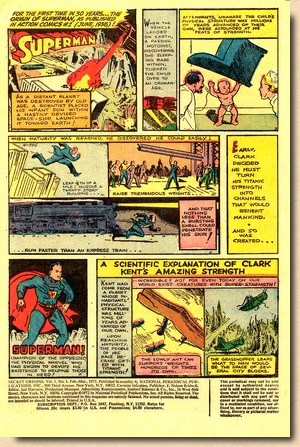

The first

issue featured origin stories of Superman (from Action

Comics #1, June 1938), Batman (first two

pages from Detective Comics #33,

November 1939), Ghost (from Flash Comics

#88, October 1947), and Flash (from Showcase

#4, September 1956). It also featured an entire

page penned by editor E. Nelson Bridwell,

providing some background for the title.

"When we decided to

publish a comic magazine featuring the

origings of the great DC heroes and villains,

we began digging back into the past to find

when and where the origins were first

printed. We made some surprising discoveries.

Take Superman.

His origin was first told in Action

#1 - yet that version was

one which had never

been reprinted! What a collector's item! So

you have it at last - in this mag."

DC was

definitely trying, and more mature comic book aficionados

will no doubt appreciate the depth of DC's

history and the material made available in Secret

Origins. But if you weren't a die-hard DC

fan at the time (and after all Infantino and

Bridwell were trying to at least hold their

ground if not expand their market base here), Secret

Origins was probably only able to generate

limited interest.

Marvel even

put DC in a tight spot in terms of sales pitch

terminology; after all, how often had Stan Lee

told potential buyers in a cover or splashpage

blurb that they were looking at an "instant

collector's item" - not from 1938, but fresh

off the press.

It probably

also didn't really help that Superman and Batman

together only covered a total of 3 pages, whereas

the Ghost got 9 and the Flash 12. In that

respect, Nick Cardy's newly produced cover was

nice, but slightly misleading.

|

|

| |

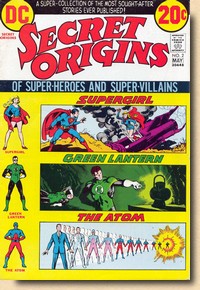

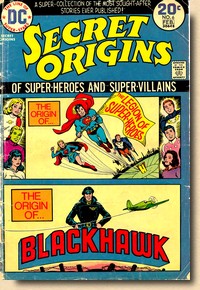

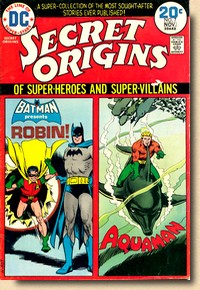

| Secret Origins #2

featured the origin stories of Supergirl (from Action

Comics #252, May 1959), Green Lantern (from Showcase

#22, September 1959), and the Atom (from Showcase

#34 (September 1961). E. Nelson Bridwell again provided

some background (on the origins of Green Lantern and the

Atom), but this was now down to one third of a page.

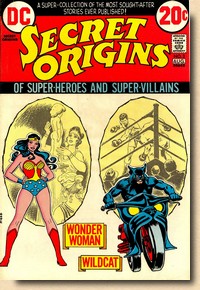

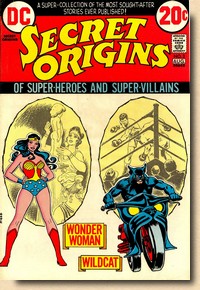

Secret Origins #3 was down to two

reprinted origin stories, those of Wonder Woman (from Wonder

Woman #1, Summer 1942) and Wildcat (from Sensation

Comics #1, January 1942). The title was still on a

bi-monthly schedule but appeared in the July/August 1973

publication slot. This was because DC discovered another

point that put them at a disadvantage with Marvel - cover

dates.

"Cover dates on comics

didn't match magazine dating norms, and by 1973

Marvel's cover dates made them appear newer than

DC's, so DC decided to skip using May 1973 and go

straight to June." (Levitz, 2010)

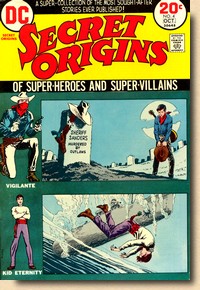

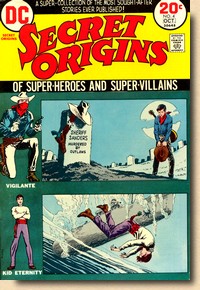

Continuing deep into Golden Age

territory, Secret Origins #4 featured Western

hero The Vigilante (from Action Comics #42,

November 1941) and Kid Eternity (Hit Comics #25

, December 1942 and published at the time by Quality

Comics).

|

| |

Secret

Origins #2 Secret

Origins #2

(May 1973)

|

|

Secret Origins

#3

(August 1973)

|

|

Secret Origins

#4

(October 1973)

|

|

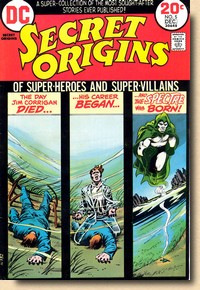

Secret Origins

#5

(December 1973)

|

|

| |

| Secret Origins #5 only

featured one single character, but although this was

another dip into Golden Age material (from More Fun

Comics #52 and #53, February and March 1940), the

Spectre must have been a lot more familiar to the average

reader than the previous issue's protagonists. |

| |

Secret

Origins #6 Secret

Origins #6

(February 1974)

|

|

Secret Origins

#7

(November 1974)

|

|

Secret

Origins #6 not only had more familiar

characters in the form of the Legion of

Super-Heroes, their origin story was also a lot

more recent material (originally published in Superboy

#147, May 1968). The Golden Age did pop up again,

though, for the origin of Blackhawk (from Military

Comics #1, August 1941, published by Quality

Comics). With the

indicia still calling it a bi-monthly title, Secret

Origins #7 didn't make it to the newsstands

until November 1974, missing three publication

slots and thus with a delay of six months.

Featuring Robin (from Detective

Comics #38, April 1940) and Aquaman (from More

Fun Comics #73, November 1941), this was to

be the title's last hurrah - unbeknownst to

readers and possibly even the editor, since the

letters page makes no mention of neither the

delay in getting this issue out nor the fact that

it will be the final one. As a matter of fact,

readers were even told to keep the letters

coming.

|

|

| |

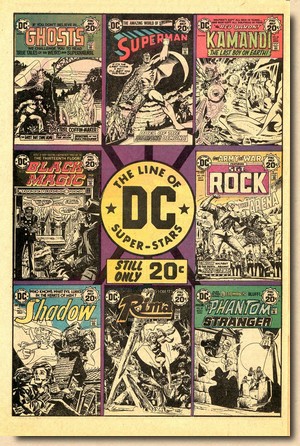

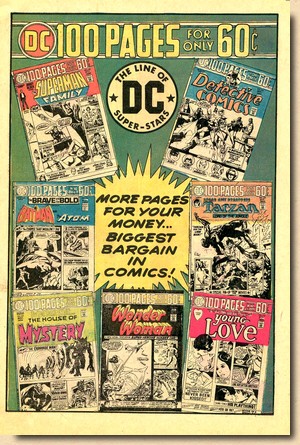

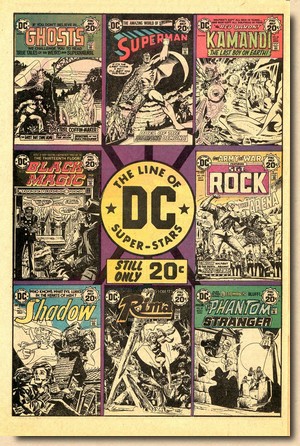

However, regular comic book

readers knew that a lengthy hiatus between two issues

hardly ever pointed to something good, and certainly not

with a bi-monthly title. The plug was obviously pulled

after all the copy for Secret Origins #7 was

already done and ready for the printers, and nobody was

going to put in an extra effort to announce the

cancellation. Interestingly enough, there are - although

admittedly with the benefit of hindsight - a few

indications which underscore the problems DC was facing

with titles such as Secret Origins. Two in-house

ads show that DC had, by now, decided to go with

characters and titles that had a long standing and were

well know (Superman leading the way, but also

including Kirby's Kamandi and, interestingly,

the reprint Black Magic, as well as popular

culture icons such as The Shadow) - and that, as

far as the war of the shelves was concerned, DC decided

to fight back with bigger titles instead of more titles.

"What DC lacked in

quantity, it (...) made up for in size. The majority

of Marvel's comics were in the standard 36-page, 25¢

format, with its Giant-Size books delivering 68 pages

for 50¢. DC, on the other hand, dove back into the

giant-size comics in a big way in early 1974 (...)

Twelve ongoing comics were published as 100-page

bi-monthly series between March 1974 and April 1975 -

nearly a third of National's full line of books at

the time (...) [featuring] a mix of new stories

alongside reprints of classics culled from DC's deep

library of archival material." (Sacks,

2014)

|

| |

|

| |

| DC simply had a fundamental

problem with its reprints, mirrored by a letter published

in Secret Origins #7, where a reader wrote about

the "crude writing and artwork"

(concerning the Spectre story from 1940). The material

was, quite simply, too old and couldn't even compare

favourably with Marvel's reprints of the Lee/Kirby/Ditko

monster stories from the 1950s. In DC's defence, it has to be said that -

according to the Statement of Ownership, Management,

and Circulation (which had to be printed once every

twelve months in order to qualify for Second Class

shipping for printed matters) - Superman was

still the best selling title across the board in 1973,

with an average of 309,300 sold copies per issue. The bad

news was that Amazing Spider-Man had

continuously been closing the gap, selling an average

273,400 copies per issue in 1973 (while Batman

stood at 200,500). Only one year later, in 1974, Amazing

Spider-Man would edge past Superman

(288,200 versus 285,600), and whilst the Man of Steal

managed to claw back once more in 1975, Amazing

Spider-Man would just keep pulling away as of 1976 -

all to the tune of dropping sales figures across the

board. These numbers are just another indication that

Marvel's "new" kind of superhero was clearly

ahead of DC's more "traditional" fare in terms

of popularity and therefore sales. Marvel was winning the

contest for very specific reasons, and a reprint title

such as Secret Origins not only failed to

address those, it almost amounted to putting DC's

shortcomings on display for all to see (possibly even

more so than Legion of Super-Heroes).

"[DC] were getting

their asses kicked in by Marvel at the newsstands

[but] they were not reading the Marvel books - never

analyzing or trying to figure out what the

competition was doing (...) you would talk to these

people and they wouldn't know what was going on in

the business except at DC Comics." (Joe

Orlando, in Infantino & Spurlock, 2001)

But maybe DC was just throwing

titles out there - not unlike Marvel - with a "what

the heck" attitude. If it sank, it at least got a

certain presence on the newsagent shelves for a while.

For Secret Origins, that presence ended, after

only seven issues, in November 1974.

|

| |

|

| |

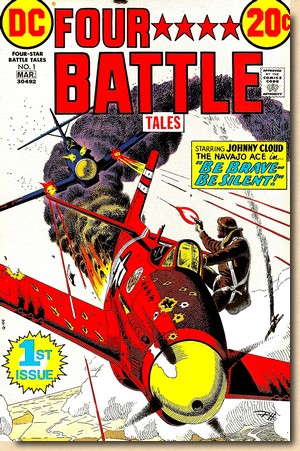

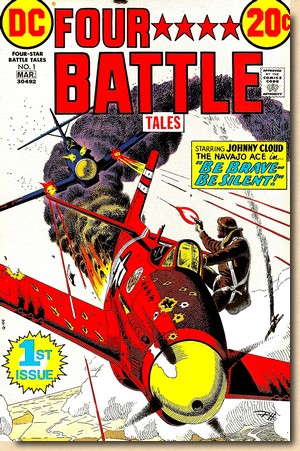

Four Star Battle Tales

#1

(March 1973)

|

|

FOUR

STAR BATTLE TALES

Launched -

March 1973

Cancelled - November 1973

Number of issues - 5

Four-Star

Battle Tales started its short publication

life with a cover date of March 1973. As the

title implies, it reprinted 1950s and 1960s

covers and stories from All-American Men of

War, Star Spangled War Stories, Our

Army at War, Our Fighting Forces,

and G.I. Combat.

Some of the

talent was still associated with war genre comic

books at the time (such as Joe Kubert, who

received a special profile page in Four-Star

Battle Tales #4), while others pencillers

had since moved on to DC superheroes (such as Irv

Novick). Special editorial pages looked at

science-fiction war stories (issue #5) or the

personality of Lawrence of Arabia (issue #1).

In 1973, DC

had the market pretty much covered for war

comics, and most of the titles which served as

source for the reprints in Four-Star Battle

Tales were still ongoing books: Our Army

at War (featuring Sgt Rock), Our

Fighting Forces (featuring the Losers), G.I.

Combat (featuring the Haunted Tank), and Star

Spangled War Stories (featuring the Unknown

Soldier). Added to that fold was the

genre-crossover title Weird War Tales.

Trivia note:

Although the indicia identified the title as Four-Star

Battle Tales, the cover copy actually always

displayed the title as Four **** Battle Tales.

|

|

| |

|

| |

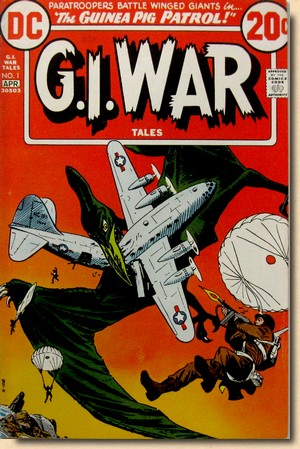

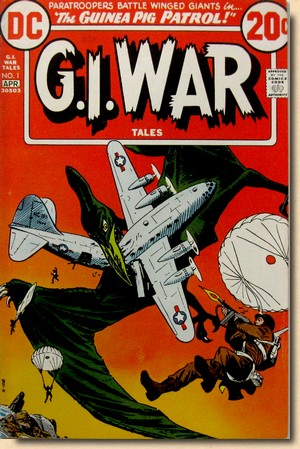

G.I. War Tales

#1

(March 1973)

|

|

G.I.

WAR TALES

Launched -

March 1973

Cancelled - October 1973

Number of issues - 4

G.I. War

Tales was also launched in March 1973, and

just like Four-Star Battle Tales reprinted

1950s and 1960s covers and stories from Star

Spangled War Stories, Our Fighting Forces, Our

Army at War, All-American Men of War,

and G.I. Combat - in other words exactly

the same sources.

As mentioned,

DC had been the undisputed number one in the

field of war comics for a long time, with strong

original characters and highly influential

creative talent.

|

|

| |

| Throwing out two reprint titles at

the same time was clearly a grab for shelf space, but it

was also a legitimately valid business idea. Unlike with

superheroes, material from the 1950s and 1960s was still

valid fare for fans of war comics. However, even so, G.I.

War Tales got decommissioned after only four issues.

|

| |

|

| |

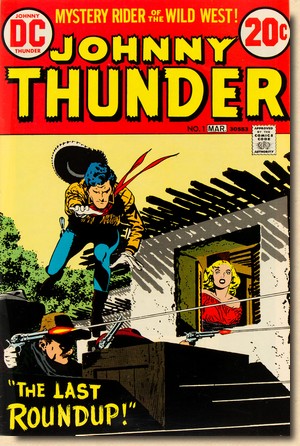

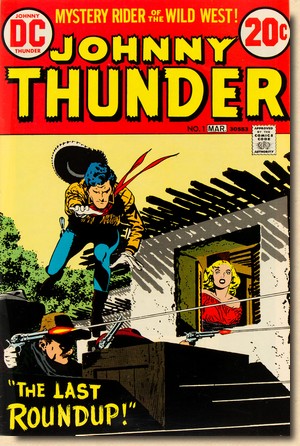

Johnny Thunder

#1

(March 1973)

|

|

JOHNNY

THUNDER

Launched -

March 1973

Cancelled - August 1973

Number of issues - 3

Johnny

Thunder was the first of two western genre

reprint titles DC launched in 1973; as the title

implies, it featured stories starring John Tane.

The son of a sheriff, he followed in his mother's

footsteps and became a schoolteacher but finds

himself increasingly at odds with the promise he

made to his mother never to use guns. In order to

keep his vow yet still fight the evil he

encounters the way his dad did, he creates a

fictional persona named Johnny Thunder, the

identity of which he assumes by changing clothes

and blackening his hair.

With an origin

story that clearly leans into the general

superhero concept of a "secret

identity", Johnny Thunder was created by

Alex Toth and Robert Kanigher for All-American

Comics #100 (August 1948) - and was actually

one of the first non-superhero characters

published by DC Comics. All-American Comics

would be renamed All-American Western in

November 1948 with Johnny Thunder as the cover

feature. Editor E. Nelson Bridwell again provided

some background information on Johnny Thunder in

issue #1.

|

|

| |

| Western comics became popular in

the years immediately following World War II when

superheroes went out of style, and all of the big comic

book publishers started putting out Western titles around

the time DC launched Johnny Thunder. Their popularity

peak around 1960 (not the least because Westerns were all

over American TV) before the genre in general started to

lose its appeal. As far as comic books were concerned,

the interest swung back to superheroes, although a

handful of titles remained, answering to a (fairly solid)

niche demand. DC had tried to

latch onto the darker reflection of the Wild West shown

by Western movies of the 1960s by setting up a

"weird western" sub-genre in 1968, ultimately

leading to Weird Western Tales in 1972 and its

newly created Western anti-hero Jonah Hex. The formula

worked, and editor Joe Orlando even derided Marvel's more

traditional Western fare ("Kid titled Western

heroes") on the letters page of

Weird Western Tales #15 (December 1972):

"It's really a

pleasure to see hard work rewarded. It would have

been much easier to put out half a dozen

"Kid" titled Western heroes - all fighting

in improbable situations - and all exactly alike.

Time has been taken to develop all the characters

that have appeared in WWT [Weird Western Tales] -

beginning with Outlaw and El Diablo and through Billy

the Kid and Jonah Hex. It has been our thought that

quality Western stories can exist (...) We will

continue to take the time to develop our characters

rather than merely xerox them."

|

| |

In that sense, Johnny Thunder

was somewhat out of time, reprinting stories

originally published between 1948 and 1957 in All-American

Western, All Star Western and Western

Comics. In issue #1 E. Nelson Bridwell had

encouraged readers to send in their feedback, and

in issue #3

revealed that exactly five had done so - and

that this would be the last of Johnny Thunder.

"This

page contains all the letters received so far

on the first issue! That may help to explain

why this is the last issue of Johnny Thunder

(...) maybe today's Western readers go more

for the Jonah Hex type than the clean-cut

range riders of the past."

Maybe E.

Nelson Bridwell ("Mr. Bridwell" to four

of the five letter writers) should have just

asked Joe Orlando beforehand.

|

|

|

|

| |

| From a more general perspective, Johnny

Thunder #3 shines an odd light on DC Comics. While

one might applaud the editors for not trying to simply

copy Marvel's flamboyant style and Stan Lee's hyperbole,

the tone displayed here is right at the opposite end of

the scale, as editor Bridwell comments on the

cancellation of Johnny Thunder with "at

least Shazam! is doing well" and an in-house ad

for the new and upcoming Prez title simply

states "coming".

It all felt very underwhelming, rather resigned, and even

self-deprecating - almost as though DC knew it was losing

ground to Marvel but still, and for the life of them,

just couldn't figure out and understand why. |

| |

|

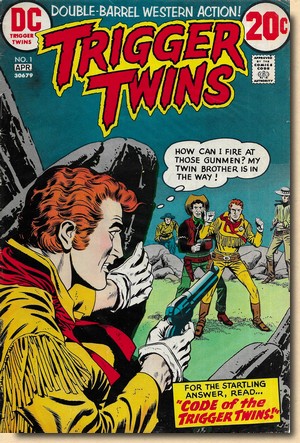

| |

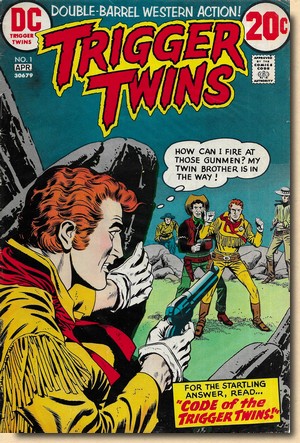

Trigger Twins

#1

(April 1973)

|

|

TRIGGER

TWINS

Launched -

April 1973

Cancelled - April 1973

Number of issues - 1

Trigger

Twins has the dubious honour of being the

1973 reprint title with the fewest issues - one.

As its title implies, it reprinted two 1957/58

stories from All Star Western featuring

the Trigger Twins as well as one 1960 story

featuring Pow-Wow Smith from Western Comics.

The cover itself is a reprint (as was th case

with all three of the Johnny Thunder

covers), taken from All Star Western #94

(April 1957).

The Trigger Twins first

appeared in All-Star Western #58 (May

1951), created by Robert Kanigher and Carmine

Infantino. The core idea was a sheriff named Walt

Trigger who, unbeknownst to the general public,

has a twin brother (Wayne Trigger) who isn't in

law enforcement but is more accurate and faster

on the draw with firearms than his brother. As a

consequence (and running theme) Wayne

impersonates Walt repeatedly - and even requires

a twin of Walt's horse to make sure no one

suspects the switch of the two twins.

Not

surprisingly, this concept didn't really hold up

for long. Again, as with the other reprint

titles, E. Nelson Bridwell introduced the

backgrounds of the Trigger Twins and Pow-Wow

Smith but already mentions that "due to

scheduling changes, it is only planned as a

one-shot (unless it sells very well, in which

case a comeback is possible)".

|

|

| |

| The indicia was even more

optimistic than Bridwell entertaining the possibility of

the title selling "very well", indicating a

bi-monthly publication schedule. But the reality was that

Trigger Twins didn't survive the first standoff. |

| |

|

| |

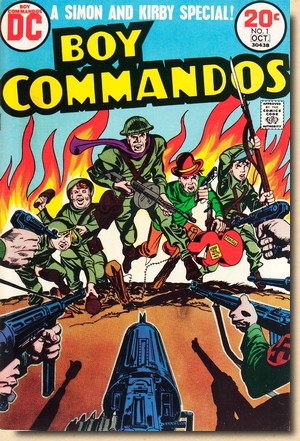

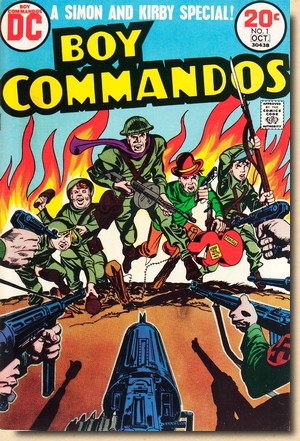

Boy Commandos

#1

(October 1973)

|

|

BOY

COMMANDOS

Launched -

October 1973

Cancelled - December 1973

Number of issues - 2

DC had thrown

out a number of reprint titles for the first

quarter of 1973, but a few months into that year

realized that none of it was selling. Having seen

superhero, war and western material fizzle out,

Infantino made a last effort ditch to stem the

tide of Marvel titles (which was still surging

and hitting the newsstands relentlessly) at least

a little bit. And this time, DC would bring out

its secret weapon - the thorn in Marvel's side:

Jack Kirby.

It was already

over two years ago that Carmine Infantino had

contracted Kirby away from Marvel (back in

February 1970), but "the King" leaving

the House of Ideas had caused shockwaves. Maybe

some of that party killing effect could be

repeated.

In putting out

Boy Commandos (volume 2) for the October

1973 cover date production cycle (issue #1

actually went on sale at the end of June), editor

E. Nelson Bridwell certainly tried to make

certain that readers knew this was Kirby - a

"Simon and Kirby Special", in fact.

Inside, readers would find some of the very first

Boy Commandos stories Simon and Kirby had

created, back in 1942, when they had been signed

on by DC, and "kid gangs" seemed to be

increasingly popular.

|

|

| |

| But the rather unfortunate

Bridwell - who again put together some background notes

for Boy Commandos #1 - was faced with the

familiar problem these reprint titles all shared (yes, it

was Kirby, but it was mid-1940s material and it felt old,

even by reprint standards). Plus he had a new problem,

too - the label "Kirby" wasn't really selling

all that well at DC. Most of his Fourth World titles had

been cancelled the year before, and in August 1973 Kirby

would be notified that Mister Miracle would be

dropped as well. Kid gangs

were no longer popular in 1973, and Boy Commandos

folded after only two bi-monthly issues, only just making

it past Trigger Twins.

|

| |

|

| |

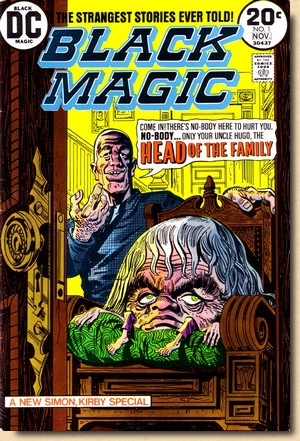

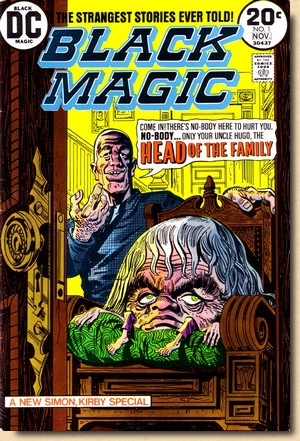

Black Magic

#1

(November 1973)

|

|

BLACK

MAGIC

Launched -

November 1973

Cancelled - May 1975

Number of issues - 9

The final

reprint title that DC launched in 1973 was

another "Simon / Kirby Special": Black

Magic. Reprinting stories from the mid-1950s

Prize Publications series of the same title

(Prize left the comic book business in 1963,

selling their properties to DC), there was no

background information from E. Nelson Bridwell

for Black Magic, since Joe Simon himself

was the editor of the reprint title.

Published

every other month, Black Magic was

probably the closest DC ever got to Marvel's

reprint titles (some of which also repackaged

1950s Kirby monster fare), although ironically

the material

wasn't actually marked as reprints, neither through an editorial

textbox on the first page of the stories nor in

the indicia (a somewhat frivolous procedure, but

one also pursued for a time in the late 1960s by

Marvel, although they never completely dropped

the word "reprint" from the

indicia).

Black

Magic would last for nine issues until the

curtain call came in May 1975, and when it did

bow out, it was the last title standing from

Infantino's 1973 attempt to curb Marvel's attempt

to bully DC off the newsstands and shelves.

It is probably

also the 1973 reprint title which today enjoys

the most attention, since the nine Black

Magic titles provide a far easier access to

these stories than the original first volume

issues do.

|

|

| |

| However, some of the artwork had

been reworked for the reprints, and since the original

Prize issues were pre-code, a few actual alterations had

to be made in 1973 in order to conform to the Comics Code

(Mendryk, 2009). |

| |

| |

|

| |

| To say that DC Comics lost the

"war of the shelves" would be an

understatement; by the end of 1974, Marvel titles on the

newsstands outnumbered DC's two to one. |

| |

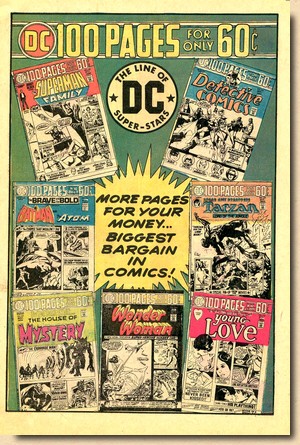

And although that kind of expansion

would not prove sustainable for the House of

Ideas, the lines were drawn.

This was also true in terms of

publishing policies. Halfway through the year

1973 DC dropped the attempt of bolstering the

title range by having regular comic books

featuring only reprint material and instead went

for the 100 pages Super Spectacular

formula, combining some new material with mostly

reprint pages.

In fact, when

Detective Comics changed to

the 100 pages format for its December/January

1973/74 issue, a lot of the reprint material

wasn't even Batman related...

|

|

... as astute

readers could notice in advance from the cover of

Detective

Comics #438

shown

in an in-house ad from Black Magic #1).

|

|

| |

It seemed like this was the only

way DC could sell any reprints at all: if readers wanted

to keep following their favourite hero's current

adventures they would have to put up with getting any and

all kinds of reprint material stuck into that same comic

book. And naturally, they would have to pay extra for

that. Not surprisingly, the move wasn't really the silver

bullet DC may have hoped for.

"While the 100-page

package was popular with DC's staffers, it faced

resistance from both fans and distributors (...) some

consumers balked at the inflated price point,

especially because the majority of material within

each issue was reprints."

(Sacks, 2014)

DC was trying different publishing

concepts for their reprint material, but unlike Marvel,

they didn't really have an idea of how to sell it -

something which the House of Ideas had been doing

systematically (and very successfully) since the early

1960s. But then, as pointed out again and again here, the

fundamental problem was that DC's archival material

simply wasn't in demand - it was the old stuff that had

been pushed aside by Marvel's new approach to comic books

since 1961. Even Carmine Infantino himself knew that all

too well, reflecting on his promotions to Editorial

Director in 1967 and then DC's Publisher in 1971:

"The DC books were

very sterile-looking in those days."

(Infantino & Spurlock, 2001)

Of course that was exactly the type

of material (or even older) that DC was trying to sell as

reprints in 1973. But unlike today, there was no sizeable

customer base made up of adults who either felt nostalgic

or were interested in comic book history. Kids and

teenagers wanted new, exciting stuff.

|

| |