|

|

|

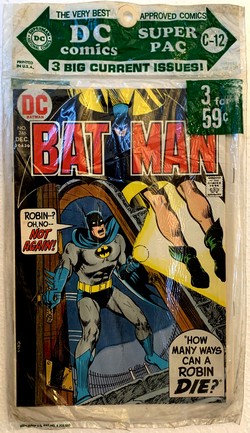

BATMAN,

FLASH & SUPERMAN

BACK

TO BACK IN A

DECEMBER

1972 DC SUPER PAC

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

DC

COMICS SUPER-PACs |

|

Even in the early

1960s, the comic book industry

realized that in spite of the

hugely successful comeback of the

superhero genre (which had been

clinically dead for most of the

1950s) and the subsequent streak

of new creativity and enthusiasm

it generated, its traditional

sales points were fading away.

Small stores that had carried

comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and

supermarkets, and newsagents

started to view the low

cover prices and therefore tiny

profit margins comics had to

offer as a

nuisance. Many ideas on how

to turn these developments around

were put forward by different

publishers, but the most

successful concepts strived to

open up new sales opportunities

and markets and thus tap into a

new customer base.

|

|

|

|

| |

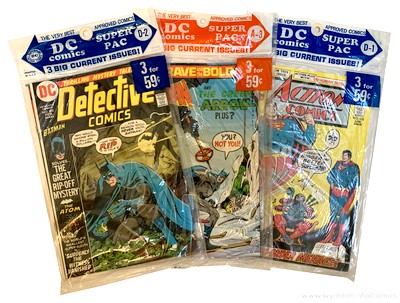

| One place these potential

buyers could be found was the growing number of

supermarkets and chain stores. But in order to be able to

sell comic books at supermarkets, the product would have

to be adjusted. |

| |

| Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This resulted in a higher price

per unit on sale, which made the whole business

of stocking them much more worthwhile for the

seller. The simple packaging was also rather

nifty because it clearly showed the items were

new and untouched, while at the same time

blending in with most other goods sold at

supermarkets which were also conveniently

packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

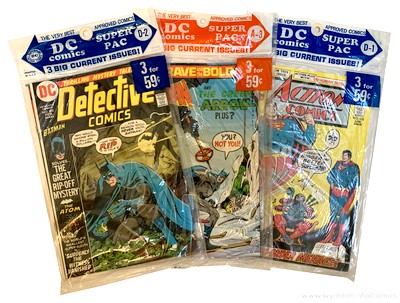

| Outlets were even supplied with dedicated Comicpac

racks, which enhanced the product appeal even more since

the bags containing the comic books could be displayed

on rack hooks in an orderly and neat fashion.

It

didn't really matter therefore that buying these three

comic books in a comicpack for say 59¢ (rather than from

a newsagent for 60¢ in that

case) clearly presented no real

bargain - it was the opportunity and convenience to pick

up a few comics at the same time parents and adults did

their general shopping. Neatly packaged, it almost became

an entirely different class of commodity.

|

| |

|

|

DC's

"comicpacks" were, in a word, a

success - so much so that other

publishers quickly started to copy it.

"DC's

focus [for the Comicpac] was on both

the casual reader and the parents and

grandparents who were looking for

gifts." (Wells, 2012)

By the early

1970s, DC relaunched their comicpacs,

calling them DC Super Pacs, and

they continued to sell well.

"The DC [comic packs]

program lasted well over a decade,

with pretty high distribution

numbers. The Western program was

enormous - even well into the '70s

they were taking very large numbers

of DC titles for distribution (I

recall 50,000+ copies offhand)."

(Paul Levitz, in Evanier 2007)

|

|

|

| |

| Unlike comic books distributed to news stands and

other traditional outlets, comicpacks were

non-returnable. Bags that didn't sell were thus the

retailer's problem, not the publisher's (leading some

distributors and retailers - who most likely had

previously rigged the returnable comic scheme, e.g. by

selling comic books without their covers - to simply

split the packs open and return the loose comics). |

| |

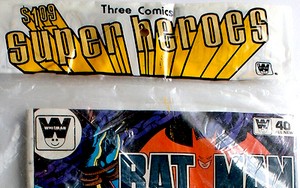

| The only way to stop such illegal

behaviour was to make comic books contained in

comic packs distinguishable from regular news

stand editions - and Western, the largest

distributor of comic packs, did just that as of

1972 by introducing their logo on the cover. DC

titles distributed by Western in their own

comicpacks featured the Western "smiling

face" logo instead of the DC roundel; the

covers would also not show the issue number and

the month.

DC's own comicpacks, however, continued to

contain regular newsstand editions only

throughout the 1970s.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

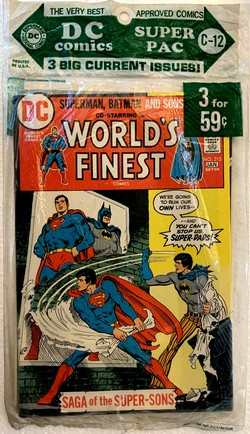

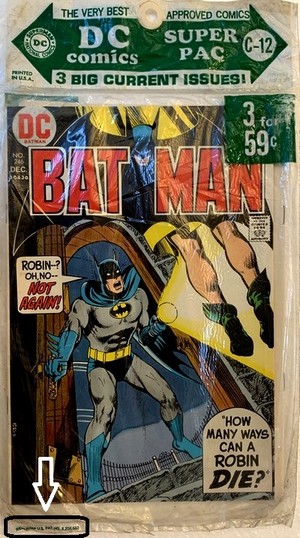

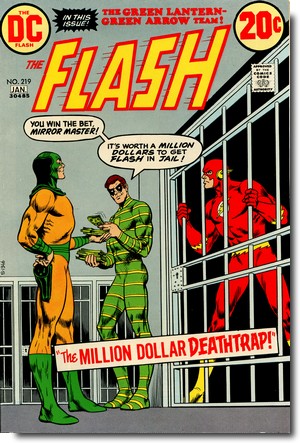

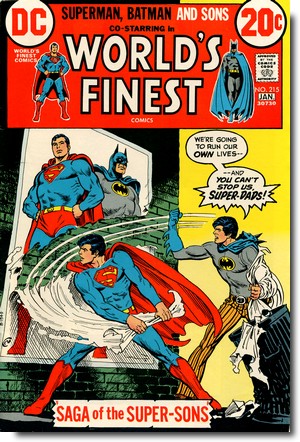

| This December (C-12) 1972 DC SUPER PAC contains Batman #246, Flash

#219, and World's Finest #215, and even

though these titles feature major DC characters (Batman,

Superman, Flash, Green Lantern, and Green Arrow), none of

them was published monthly at the time. As a consequence,

only Batman #246 carries a December cover date

(the title was published eight times a year, including in

December), whereas Flash #219 and World's

Finest #215 display a January cover date (in the

case of bi-monthly publication, DC would print the second

month on the cover, thus making the title appear

"new" on shelves and racks for a longer period

of time). Right from the start in

1961/62, when DC Comics launched the Comicpac,

all of their multi-comic packs were reference-numbered

using a letter plus digit, e.g. B-3. And since DC wasn't

just filling plastic bags at random with any comic books,

a B-3 pack from a specific year would carry the same

titles and issues no matter where or when it was sold

(rare packaging errors aside).

|

| |

|

|

By

1964 the digit would refer to the month,

i.e. A-1 and B-1 would both feature comic

books with a January cover date (or

January/February in the case of

bi-monthly titles), and four packs (A

through D) per month were the rule from

mid-1972 to 1978 (when DC ended their own

comicpacks). "C-12"

therefore denotes the third December

SUPER PAC, in this case from 1972.

|

|

|

| |

| |

| No titles had truly

permanent slots in the SUPER PACS, although there was a

high level of consistency with DC's flagship characters

(the data for 1973, for example, shows that the

SUPER PACs of that year offered buyers complete runs of Superman

and Batman as well as the Batman team-up title Brave

and the Bold). But since

sales points could vary a lot with regard to their

supplies and selection of SUPER PACs, the availability of

specific titles was never guaranteed. However, one needs to bear in mind that

this was a common fate of the average comic book reader

in the 1970s Bronze Age, whether his or her comic books

came packaged in a plastic bag or as single issues from a

display or spinner rack. Back in those days, an

uninterrupted supply of specific titles was, quite

simply, never truly guaranteed. In the case of DC titles this mostly

wasn't a problem anyway. Unlike their major competitor

Marvel, DC's editorial at large still very much embraced

the "single issue, done in one" storyline

principle, so it often didn't even matter in which

sequence you read your copies of Batman or Superman,

since every issue would start with a brand new story

(there were, of course, exceptions).

Also very much unlike Marvel, DC

had no regular editorial feature across its titles at the

time, through which the publisher would communicate with

its readership (the way Marvel and Stan Lee did with

their famous Bullpen Bulletins); the interaction

with fans and readers was limited to the letters pages,

and plugs for other titles restricted to in-house ads.

|

| |

|

| |

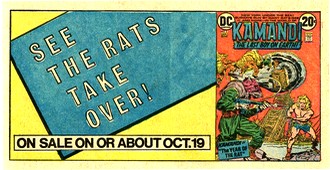

| Whether you were a DC fanboy or one of Marvel's true

believers back in 1972, it would probably have been hard

to disagree that the House of Ideas definitely had the

upper hand when it came to making in-house ads look

attractive and trumping up a hype for a title or the line

in general. |

| |

|

| |

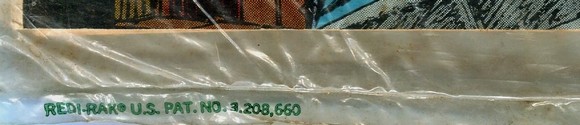

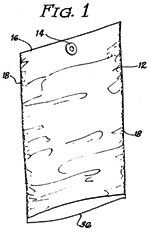

| This SUPER PAC also provides

some additional information on the packaging material and

process, thanks to a printed line of text on the

polybag's lower left hand corner which refers to a

registered trademark (REDI-RAK) and a U.S. patent number

(3.308.660). |

| |

|

| |

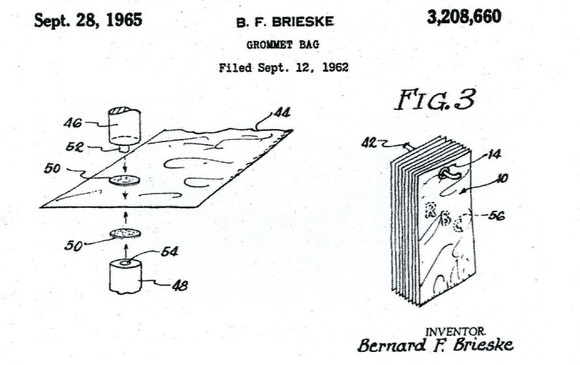

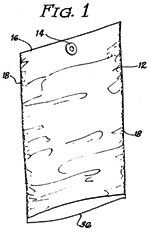

| The patent concerned was filed in 1962 and registered

in 1965 by Bernard F. Brieske, who registered a number of

US patents in conjunction with the production and usage

of packaging items (such as polybags), in conjunction

with Illinois-based Vision Wrap Industries (who had the

Redi-Rak name trademarked in 1969). Only a small handful

of SUPER PAC polybags carry that reference. |

| |

| The patent "is

particularly directed to bags or similar

containers which are formed of polyethylene and

which are provided with grommets whereby the bags

can be effectively employed for rack

merchandising and for similar uses". As

such, this system would do away with any added on

hanging labels (as seen on the very first

generation of DC Comicpacs) as these would become

an integral part of the packaging.

The patent

also illustrates how the polybags were filled

from the bottom:

"Where (...) sections [of

polyethylene] are employed, a heat seal is

provided along the end of the bag which has

the grommet adjacent thereto. In the normal

course, the package manufacturer will market

a bag of this type with an open end whereby

the persons interested in using the bags can

heat seal or otherwise close off this end

when the goods are inserted in the bag. For

display purposes, the grommet end of the bag

would then become the top of the bag."

|

|

|

|

| Many important questions still remain open regarding

the packaging of comicpacks (most importantly where it

was done and by whom), but this little snippet of

information on the polybag of the C-12 December 1972 SUPER PAC at least sheds a

little bit of light on this aspect. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

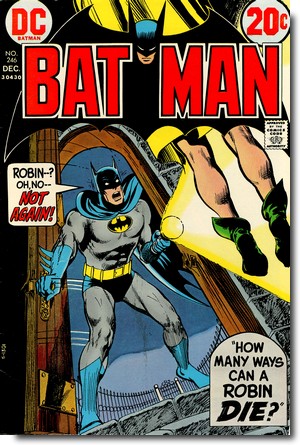

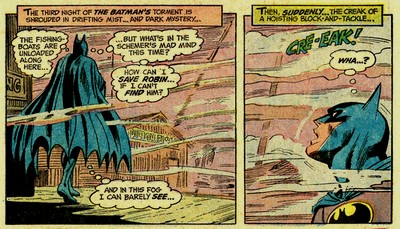

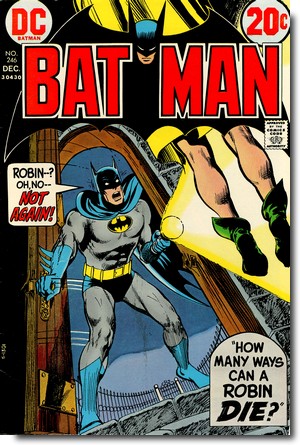

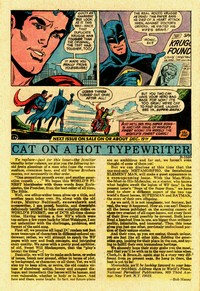

BATMAN

#246

December 1972

(monthly,

with the exception of January,

March, July and November)

On Sale:

19 October 1972

Editor

- Julius Schwartz

Cover - Dave Cockrum (pencils) & Neal

Adams (inks)

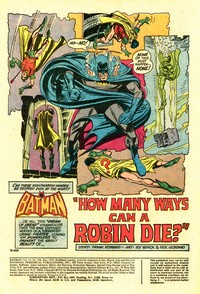

"How Many Ways Can a

Robin Die?"

(22.5 pages)

Story -

Frank Robbins

Pencils - Irv Novick (pg 1-17), Dick

Dillin (pg 18-23)

Inks - Dick Giordano

Lettering -

Ben Oda

Colouring - NN

PLOT

SUMMARY - Someone is

demonstrating ways to "kill"

Robin by using dummies and is thus

psychologically torturing Batman, who

must track down further dummies and hope

he will be in time to rescue the real

Robin from the hands of a twisted killer.

|

|

|

| |

| Batman #246 follows on

the heel of a three issue run by Denny O'Neil /

Neal Adams (including a two-issue story in which

Batman tracks Ra's Al Ghul to Switzerland) and

presents readers with some very noticeable

changes. First off, Frank Robbins spins yarns

very differently than O'Neil does, and the

artwork of this issue is even split up between

two pencillers, Irv Novick and Dick Dillin.

Robbins (1917-1994) took over writing the

Batman in 1968 from Gardner Fox, who had

essentially been pouring out stories featuring

Bruce Wayne and his vigilante alter ego since

1939.

After a transition phase (the "camp"

TV show was gone but things were still very much

tongue in cheek), Frank Robbins initiated the

character's return to his darker, more gothic

roots before O'Neil and Adams ran with it.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

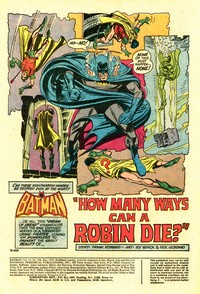

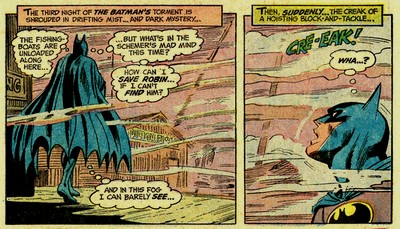

| "How Many

Ways Can a Robin Die?" may explain why

writer-artist Robbins is identified and remembered less

with Batman's transition to a darker place than is the

case with O'Neil and Adams. On its surface, the story -

divided up into no less than five chapters, all of which

sport borderline goofy titles - seems to have more in

common with the often ludicrous Batman stories from the

1950s and 1960s than with the Darknight Detective tales

from the 1970s. |

| |

|

| |

| As light-heartedly as it may be portrayed, Batman is

actually trying hard to prevent his sidekick from being

killed - in most gruesome ways, no less. And once he

catches up with the perpetrator, he lets him know that "I

am always prepared to die (...) but not at the hands of

rabid dogs like you." Those aren't just words

that Robbins has the Batman say; the Darknight Detective

does indeed view the psychopathic criminal as something

below human - which of course questions Batman's humanity

just as much in return. It is a return to the mindset of

the Batman of 1939 who threw criminals off of roofs. And

with that state of mind, with an anger barely controlled,

the Darknight Detective goes off like this on Ravek

because the criminal knew exactly how to play the Batman:

push his guilt buttons, and if Robin were to die, the

Darknight Detective would have psychologically imploded.

Ravek understood the Batman's secret weakness, and

Robbins give the readers a glimpse into a very dark

abyss, and a person only barely - and very delicately at

that - balanced.

|

| |

|

|

It is entirely

possible to read over those aspects and be left

with what then almost feels like a send-off of

those camp Batman tales. It actually works both

ways, which is a credit to Robbins.

It also works because Irv Novick

and Dick Dillin (for the conclusion) both provide

solid atmospheric artwork that reflects and

supports both the Saturday matinée

cliffhanger take and the far less optimistic

noir aspects of the story.

|

|

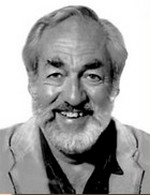

Irv Novick

|

|

| |

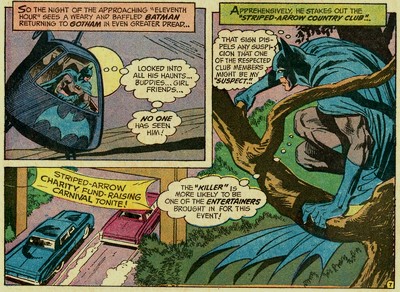

| Novick (1916-2004) graduated from the National

Academy of Design in New York City and, following a brief

stunt at the illustrator's studio of Harry Chesler in

1939, went on to spend almost his entire career in the

comic book industry. In the mid-1960s DC Comics offered

him an unprecedented freelance contract which guaranteed

him the highest artist's rate plus a steady amount of

work. In essence, this meant that as soon as Novick had

finished a job he was to immediately receive another

assignment - which explains his substantial body of

artwork for DC over the years. |

| |

| When Carmine

Infantino became a part of DC's

management in 1968 he made sure

that Novick became a full-time

superhero penciller, thus

providing the artwork for most of

DC's top titles of the genre,

including numerous contributions

to Batman and Detective

Comics. Irv Novick had a

substantial part in shaping the

visuals of Batman during the late

1960s and all throughout the

1970s. Retaining his very own

style, he (together with a few

other pencillers) fleshed out the

popular culture icon look which

Neal Adams had created, and left

a lasting contribution to the

hallmark appearance and visuals

of the Darknight Detective -

which still remain iconic to this

day.

His pencils had a classic

touch in the best sense of the

word, and his pictorial

storytelling was fresh and

dynamic and even made some of the

lamer plots of the Bronze Age

look interesting.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

With a little bit

of luck, regular buyers of DC's

SUPER PACs would be able to pick up

the next issue of Batman

too - as

Batman #246

would be contained in the 1973

B-2 SUPER PAC (albeit

slightly hidden as the middle

comic book). |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

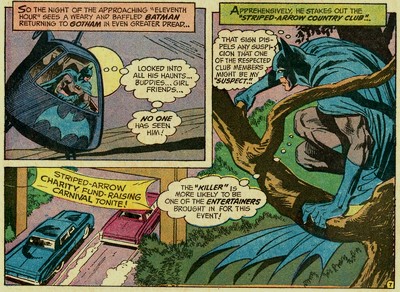

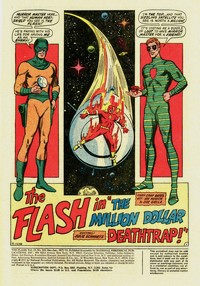

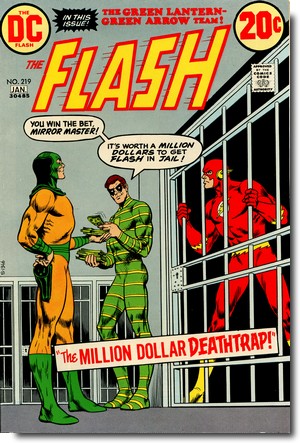

FLASH #219

December/January

1972/73

(bi-monthly)

On Sale:

17 October 1972

Editor - Julius

Schwartz

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

FLASH:

"The Million

Dollar Deathtrap"

(13.5

pages)

Story

- Cary Bates

Pencils - Irv Novick

Inks - Joe Giella

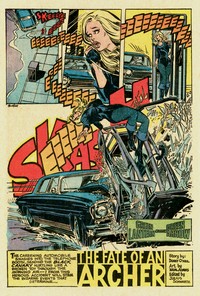

GREEN

LANTERN & GREEN ARROW: "The

Fate of an Archer"

(9.5

pages)

Story

- Denny O'Neil

Pencils - Neal Adams

Inks - Neal Adams

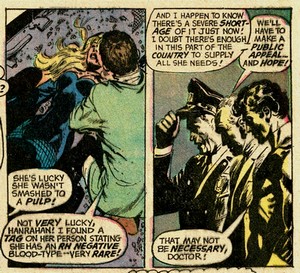

PLOT

SUMMARIES - The

Top makes a million-dollar bet

with Mirror Master that he cannot

escape prison and destroy the

Flash with his optical weapons,

and the Mirror Master takes him

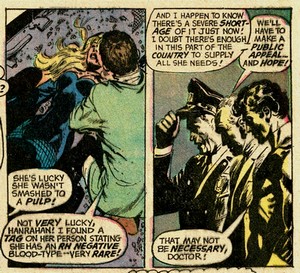

up on it. / After Black Canary is

hit by a car she urgently needs a

blood transfusion. Green Arrow

shares her rare blood type, so

Green Lantern sets out in search

of the archer.

|

|

|

|

| |

| The Flash was a

regular title in DC's SUPER PACs, and although

its

namesake character is a mainstay in the DC Comics stable,

the series has been cancelled and restarted several

times. |

| |

| The first volume, starring Barry

Allen as the Flash, picked up the numbering of

the original Flash Comics with issue #105

(March 1959) and ran until issue #350 (October

1985). In one of DC's first (and often

confusing) switches in alter egos, Barry Allen

would then die in Crisis on Infinite Earths

and Wally West, Allen's sidekick Kid Flash, took

up his uncle's mantle as the Flash. Somewhat

similar to Batman's sidekick Robin, DC now sports

several different Flashes, depending on what

volume of the title (and possibly what parallel

DC universe) you're looking at.

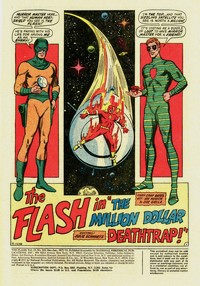

Flash #219 features the original DC

Flash, as well as his first ever villain, Mirror

Master (whom he encountered in his first

adventure, back in Flash #105), together

with The Top - and the overall result actually

looks and feels like an early 1960s comic book

story, rather than one from 1972.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Comic book publishers with established and popular

characters have traditionally strived to ensure that

their visuals remain identical. Disney has always had a

very strict "house style" policy in that

respect, instructing artists in great detail how to draw

its characters, because Mickey Mouse and Donald Duck and

all the others should always look the same, regardless of

the creative talent involved. A similarly strict policy

was in place at DC Comics.

"DC artists were forced to work within an

established house style that governed the page layout

as well as the look of the artwork. Editor Julie

Schwartz's motto was 'if it's not clean, it's

worthless'." (Tucker, 2017)

|

Carmine

Infantino

(1925 - 2013)

|

|

When Carmine Infantino was

appointed DC's art director in 1967, he eased the

rules a bit in an attempt to make DC a more

welcoming place for talented artists. But general

management at DC still felt that their "safe

and polished" house style was actually

sophisticated (and more refined than anything

Marvel would ever put out), and therefore had it

continue for some characters, including the Flash

(whom Infantino had, somewhat ironically,

pencilled for years following the superhero's

relaunch in 1956). Years later, looking back to

the late 1960s and early 1970s, and reflecting on

his promotions to DC's Editorial Director in 1967

and then DC's Publisher in 1971, even Carmine

Infantino himself had to admit that

"The DC books were very

sterile-looking in those days."

(Infantino & Spurlock, 2001)

|

|

| The Flash story in Flash #219 seems like an

excellent illustration of Infantino's thoughts since,

incredible as it may seem, the penciller at work here is

the same who drew most of the Batman issue also

to be found inside this SUPER PAC: Irv Novick. |

| |

| The difference,

induced by the house style for

the Flash at the time, is

striking. It is safe to assume

that Novick simply adapted to

what was expected from him,

depending on the title, but even

if he did add more detailed

backgrounds the inker would

simply override that - especially

since the inker on this issue was

Joe Giella.

Born in 1928, his inking style

became synonymous with DC's house

style. Being the final step in

the production of the artwork

besides colouring, inkers such as

Giella were in a position to make

sure that the rules of the house

style were adhered to - an

experience even Carmine Infantino

recalled from back when he was

"just" a penciller for

Batman:

"Remember, once I

turned in the drawing, I had

nothing more to say (...)

Giella had the house style

then. It was a very slick

look, and I wasn't fond of

it, but it was the house

style." (Infantino

in Eury & Kronenberg,

2009)

|

|

|

|

|

|

The "slick look" resulted in artwork that

generally featured very little detail and more often than

not just blank or highly reduced backgrounds. It was an

approach that didn't do justice to the artwork of many

pencillers.

"[Gene Colan's 1950s] art was buried in

the DC house style inking of people like Frank Giella

and Sy Barry." (Apeldoorn, 2013)

|

| Some creative teams were able to fight off this

reductionist policy, mostly due to either working on a

failing character or title, or thanks to being fan

favourites. |

| |

|

|

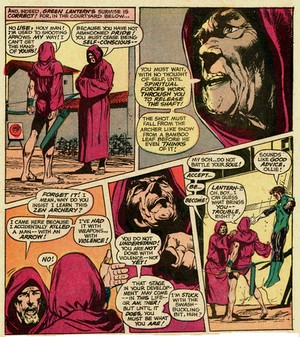

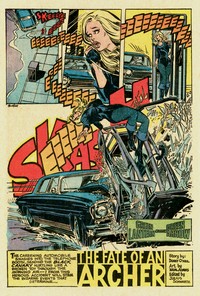

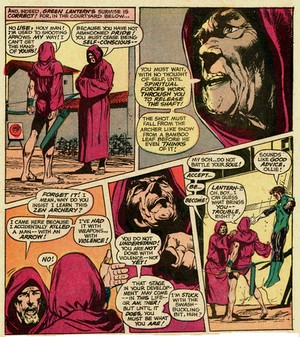

Neal

Adams and Denny O'Neil

clearly belonged to the

second group in 1972, and

so in spite of Julie

Schwartz being the

editor, Adams was able to

pursue his own style

without restrictions -

not the least due to the

fact that he inked his

own pencils. It seems

almost impossible to

imagine a starker

contrast in telling a

story through words and

images than the one

readers of Flash

#219 experienced - in

seeing O'Neil and Adams

tell a Green Lantern and

Green Arrow yarn as

compared to Bates and

Novick doing the same for

the Flash on the

preceding pages. The two

end results seemed to

come from entirely

different eras.

The impact Adams

visual approach had on

some of DC's main

characters (resulting in

an implicit new

"house style"

for Batman) is common

knowledge.

|

What

is less talked about is how the

powers in charge at DC reacted to

the fans embracing the change

both in artwork and how the

character was handled.

"I

had asked to work on Batman

many times and [Julie

Schwartz) turned me down. So

I drew Batman for several

issues of Brave and the Bold.

Letters poured into DC Comics

saying and asking "Why

is the only 'good' Batman the

one in Brave and the

Bold?" Under this

barrage of fan mail Julie

finally offered to let me

draw for the regular Batman

titles. In our hallway chat,

as he offered me the Batman

work, Julie finally said, and

with some annoyance,

"Why is it, Neal, that

you think you know how to do

Batman and all the rest of us

don't?" What I said to

Julie at the time (...) is

that it's not that I knew

what Batman should be, it's

that I and every kid in

America knew what Batman

should be." It just

didn't seem like the people

at DC Comics knew what Batman

ought to be." (Neal

Adams in Eury &

Kronenberg, 2009)

One look at the

page composition and complexity

of the artwork of "The Fate

of an Archer" embedded in Flash

#219 is enough to understand that

this didn't just apply to Batman.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The fact that readers of Flash even got to

see this was due to the faltering success of

Green

Lantern. Sales had been in a major decline for years,

and even the O'Neil/Adams stories that co-starred him

with Green Arrow ultimately failed to save the title,

which was cancelled with issue #89 (April/May 1972). The

end of the story arc of the Green Lantern/Green Arrow

series was therefore published as a back-up feature

starting in Flash #217 and ending in this issue,

#219. Prior to Flash #217 the back-up story had

featured Kid Flash, starting with Flash #220 that

spot would be given over to the solo adventures of Green

Lantern up until issue #244 (September 1976) when the

title (now reduced to a page count of 17) would drop

back-up features. |

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

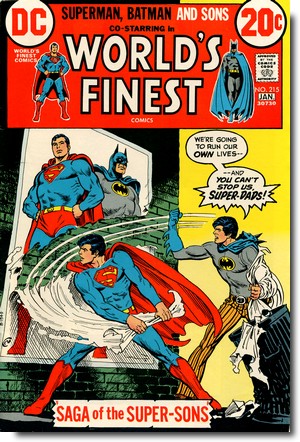

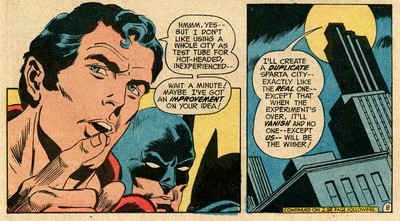

WORLD'S

FINEST #215

December/January

1972/73

(bi-monthly)

On Sale:

17 October 1972

Editor - Murray

Boltinoff, E. Nelson Bridwell

(assistant)

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

"Saga

of the Super Sons!" (23.5

pages)

Story - Bob Haney

Pencils - Dick Dillin

Inks - Henry Scarpelli

PLOT

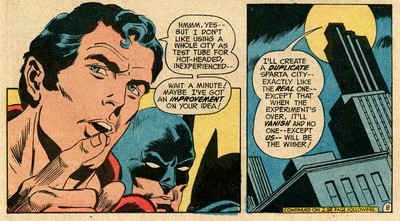

SUMMARY - Superman

and Batman are having

increasingly heated discussions

with their teenage sons about

their roles. When Superman

creates an alternate timeline and

reality in Sparta City, Superman

Jr. and Batman Jr. can explore

crime-fighting without

ramifications yet still put an

end to the local mob boss, albeit

with some unexpected help.

|

|

|

|

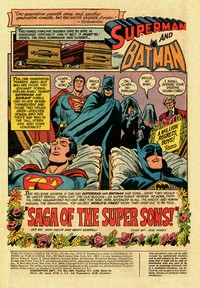

| |

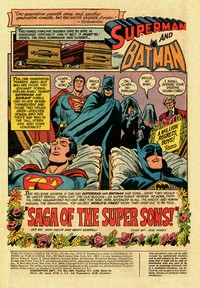

Did you ever wonder if one day Superman

and Batman had Sons...

what they would be like??

Heroic Chips off the Old Blocks -- or Super Duds? Wonder

no more, Faithful Ones!

Imagination? Put-On? No! For now, here, revealed in all

its Shock and Human Anguish,

the sensational top-secret

World's

Finest Story that cried out to be

told..."Saga of the Super Sons!"

If this (Superman and

Batman aside) sounds a lot like Marvel and not at all

like DC, then it's because of the writer - Bob Haney.

|

| |

| Robert G. "Bob" Haney

(1926-2004) started working in the comic book

industry in 1948 and joined DC in 1954, where

over the next 30 years he scripted just about

every sort of comic book DC published (Evanier,

2004). Sometimes called "Zany"

Haney, he was in actual fact one of the few

people at DC in the mid-1960s who

"understood that Marvel was

successfully reinventing the super-hero comic

for the current generation"

(Evanier, 2004)

Haney almost desperately tried to bring some

of that "Marvel flavour" to the stories

he was writing for DC, and that included his very

own (and sometimes completely off-beat) version

of Stan Lee's hyperbole - as illustrated by his

introduction to "Saga of the Super

Sons".

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| But Haney understood that readers expected the

writers of the comic books they were buying to connect

with them, and whilst he could not make DC look like an

exclusive secret club the way Marvel portrayed itself,

addressing readers as "faithful ones" was

definitely a step in the right direction. |

| |

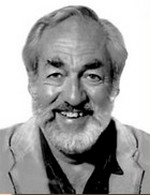

Bob Haney

|

|

He was also keenly aware

of the fact that the content itself had

to change, and his vehicle for that was

the Batman team-up series Brave and

the Bold.

"I wanted the spooky dark

night Batman image of his original

days. Such artists as Neal Adams and

the redoubtable Jim Aparo brought

this vision to panelled

reality." (Bob

Haney, in Best of the

Brave and the Bold #5, 1988)

Haney cared very little about the

conventionalities of the DC Universe and

would sometimes even write stories which

outright contradicted them - so much so

that Haney's Brave and the Bold Batman

would be deemed to be living in an

alternate reality called

"Earth-B" (Eury, 2013).

Haney could whip up tightly plotted

scripts (e.g. his classic Brave and

the Bold stories illustrated by Neal

Adams) just as easily as throwing out

extremely loose plots with lots of holes

and very little overall sense.

|

|

|

| |

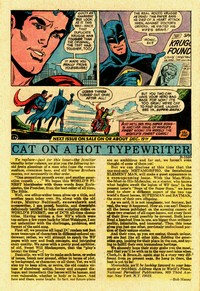

| The "Saga of the Super Sons" sits

somewhere between those two poles, especially

since it features an interesting "what

if" scenario in the premise of both Superman

and Batman having a son, even though the

"what if" concept as such was not new.

DC published a number of stories, particularly

during the 1960s, which did not take place in the

regular continuity of the featured character.

Most of these stories were labelled

"imaginary stories" and featured

alternate histories, mostly concerning Superman.

In this case, however, both the introduction and

the added explanatory notes ("Cat on a hot

typewriter") by Bob Haney made it clear that

the Super-Sons were actual stories from the lives

of Superman and Batman. |

|

| |

|

|

Richard

Allen "Dick" Dillin (1928-1980)

was in charge of pencils (as he had been

for the conclusion of Batman

#246), inked by Henry

Scarpelli (1930-2010, who is more noted

for his work for Archie Comics), and the

resulting artwork has a conventional

layout and a very clean look to it - even

in the dynamic renderings of the action

sequences. Clearly, DC's antiquated house

style was starting to give way to what

was still a very conservative style but

one that at least could be seen as being

in step with its time.

|

|

Dick Dillin

|

|

|

| |

| The Super-Sons would make subsequent appearances in World's

Finest #216, 221-222, 224, 228, 231, 233, 238 and

242, all scripted by Bob Haney. In World's Finest

#263 (July 1980) Denny O'Neil explained the Super-Sons'

existence as the result of a computer simulation, created

by Superman and Batman on the Man of Steel's computer in

his Fortress of Solitude. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

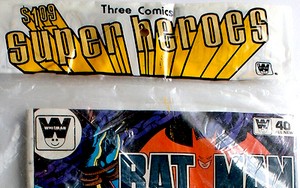

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

| APELDOORN

Ger (2013) "Hopping Along", published

online 6 October 2013 at Fabulous Fifties EURY

Michael & Michael Kronenberg (2009) The

Batcave Companion,

TwoMorrows

Publishing

EURY Michael (2013) "The

Batman of Earth-B", in Back Issue #66

(August 2013), TwoMorrows Publishing

EVANIER

Mark (2004) "On the Passing of Bob

Haney",

published online 7 December 2004 on News from

Me

EVANIER Mark (2007) "More

on Comicpacs", published online 2 May

2007 in News From Me

TUCKER Reed (2017) Slugfest:

Inside the Epic Fifty-Year Battle between Marvel

and DC, Sphere

WELLS John (2012) American

Comic Book Chronicles: The 1960s (1960-1964),

TwoMorrows Publishing

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2022

uploaded

to the web 15 January 2022

|

| |

|

| |

|