| The world of Marvel

superheroes had in many ways revolutionized the

comic book medium since 1961. It featured

individuals who in spite (or even because) of

their superhero powers had to continuously deal

with their very own problems in life. Since that

was part of the success formula, it would always

be clear what exactly the problem was. Similarly,

one could always tell the good guys from the bad

guys, and at the end of the day good would

prevail and crime would never pay. It was a clean

world, made up of primary colours, and although

there were plenty of physical clashes, blood was

never and bruises hardly ever to be seen. But throughout the 1960s the real

world was changing into a far more complex place.

Social questions and political issues made it

harder and harder to figure out or agree on what

the problems really were, and the line between

good and bad became blurred at times. Some comic

books tried to adapt to this increasingly gloomy

reality, but the superhero concept started to

feel simply too clean to a growing number of

readers - who even started writing in to Marvel,

asking for non-superhero fare (NN, 2010).

A number of publishers

started to realize that they needed to find a way

to renew their appeal to existing as well as new

comic book readers. One way of doing this was to expand into

different genres, and among these, horror stories and characters had

always been popular in times of

economic and social crises, allowing people to

project their real-life fears onto the threats

posed by vampires and ghouls and haunted houses.

Not surprisingly, horror movies had seen a sharp

surge in popularity since the mid-1960s. As far

as comic books were concerned, the shock of the

1954 US Senate hearings and subsequent culling of

EC Comics and other publishers putting out horror

titles had passed, and the days of the highly

restrictive Comics Code were clearly numbered.

|

| |

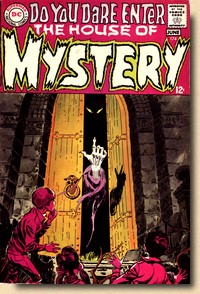

| In the early to

mid-1960s, DC Comics had followed the trend set by

Marvel and revamped its horror titles to

feature superheroes (such as Manhunter

from Mars in House of Mystery #143

- 155 [June 1964 - December, 1966] and

Dial H for Hero in House of Mystery

#156 - 173 [January 1966 - March/April

1968]). Noting

horror's resurging popularity, DC's newly

appointed Editorial Director

Carmine Infantino

acted

on the trend and brought EC Comics

veteran Joe Orlando into the DC ranks.

Appointed editor for House of Mystery,

the title once again began to feature

horror stories, and as of issue #174,

Orlando introduced Cain, the "able

care taker" of the House, followed

later by Abel in the same role for

the

House of

Secrets as of issue #81 (August

1969).

Based rather

obviously on classic EC prototypes such

as the Crypt Keeper, the characters

served as "narrators with an

attitude" (Cooke, 1998) and -

combined with covers depicting classic

horror and gothic themes and visuals -

made both titles an instant success.

"Neal

[Adams] did the best covers for House

of Mystery. Many times he would walk

in with a sketch that he had thought

up himself and I would often get a

story written for the sketch."

(Joe Orlando in Cooke, 1998)

|

|

House

of Mystery #174

(May/June 1968)

|

|

| |

| While the first few revamped issues of House

of Mystery featured a combination of

reprints with "passable new strips"

(Roach, 2001), Orlando soon stepped up the game

by bringing on board the creative talent of Neal

Adams, Alex Toth and Bernie Wrightson and turned

the title into a massive seller. Within a year,

DC had expanded its horror line to no less than

five titles: House of Mystery, House of

Secrets. Unexpected, Witching Hour and Phantom

Stranger. |

| |

| |

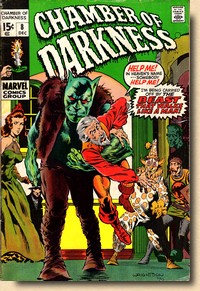

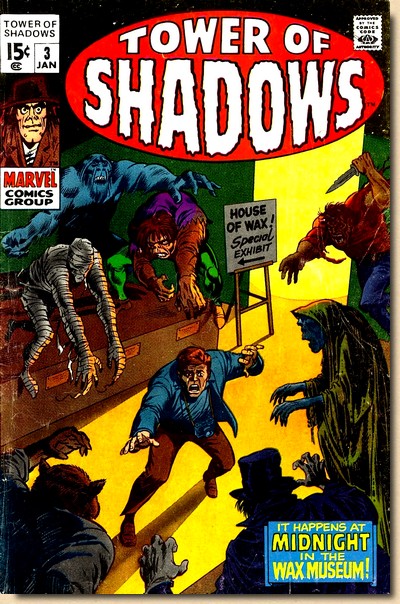

MARVEL'S

TOWER OF SHADOWS &

CHAMBER OF DARKNESS

|

| |

For the first time in

years, DC had managed to be ahead of the House of

Ideas - a fact which did not go unnoticed at

Marvel.

"DC was having some luck

with House of Mystery and House of Secrets

(...) so it was a natural to try to get back

into the genre again." (Roy

Thomas in Cooke, 2001)

|

| |

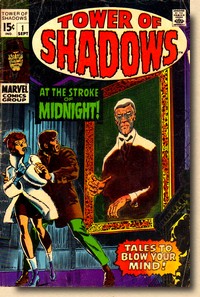

Tower of Shadows #1

(September 1969)

|

|

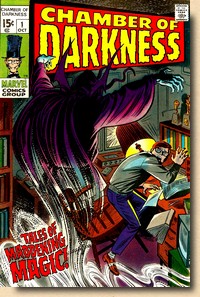

Marvel

launched Tower of Shadows #1 in

September 1969 and Chamber of Darkness

#1 in October 1969.

Reviving its own horror

genre heritage was carried out by

assigning some of its biggest talents to

the new task, including writer-artists Neal

Adams, Jim Steranko and Wally Wood,

writer-editor Stan Lee himself, and

renowned artists such as John Buscema,

Gene Colan, Don Heck, Barry Smith and

George Tuska.

The result was

top quality content for which Marvel was

rewarded at the 1969 New York Comic Art

Convention when Jim Steranko's lead story

for the first issue of Tower of

Shadows ("At the Stroke of

Midnight") won an Alley Award

for best feature story.

But in spite of

all of the great talent invested, neither

Tower of Shadows nor its sister

title Chamber of Darkness went on

to become highly successful titles -

simply because Marvel lacked the means to

provide effective editorship.

|

|

Chamber of Darkness #1

(October 1969)

|

|

| |

"[The]

problem was that, after the first

issue or two, with our being too busy

to pay a lot of attention to them,

they didn't have the focus Joe

Orlando could give to the DC books by

concentrating on a handful of titles

(...) so we just tried to hire a

bunch of people to do good stories.

But they didn't ever have any unity

(...) we really didn't have anybody

that really concentrated on that

editorially." (Roy Thomas

in Cooke, 2001)

Just as Orlando

had unapologetically done for DC's

House

of Mystery and House of Secrets,

both

Tower of Shadows and Chamber

of Darkness also made obvious

references to the classic EC horror

comics by featuring a host for each story

- such as Roderick

"Digger" Krupp (a gravedigger)

or "Headstone" P. Gravely (an

undertaker). Both characters could have

come straight from a 1950's horror comic

and thus fitted that tradition nicely.

|

|

| |

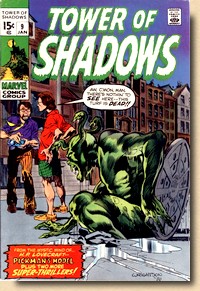

Tower

of Shadows #9

final issue

(January 1971)

|

|

But in spite of all the effort

invested, sales only went from

average to poor, making the

necessary commitment (the two

horror titles were far more

demanding in terms of editorship

in comparison to other books,

requiring three different sets of

writers and artists for every

issue) untenable.

"We

didn't have the right kind of

a set-up at the time to make

a hit of those books."

(Roy Thomas in:

Cooke, 2001)

As a

result, Marvel gradually stopped

producing original material and

began inserting more and more

reprints of 1950s monster and

sci-fi stories from the Atlas

archives as of issues #6 of both

Tower

of Shadows and

Chamber

of Darkness. Both titles soon

spun out of existence after this.

After nine issues,

Tower

of Shadows became Creatures

on the Loose in March 1971, featuring a mix

of reprints and occasional sword

and sorcery and sci-fi series

(and introducing characters

such as Kull or John Carter

Warrior of Mars) before finally

being cancelled after issue #37

in September 1975.

|

|

Chamber

of Darkness #8

final issue

(December 1970)

|

|

|

| |

| Similarly,

Chamber of Darkness became

Monsters on the Prowl with issue #9 in

February 1971, turning much into the same

direction of sword and sorcery as its companion

title as of issue #16 in April 1972 before

cancellation came in October 1974.

Over at DC, things went

much more smoothly.

House

of Mystery continued its run and eventually

clocked up a staggering 321 issues and an

incredible 32 years in publication before the

lights went out in October 1983. Its sister

title, House of Secrets, would also

outlive Marvel's anthology books by far with a

total of 74 issues before cancellation in

November 1978.

Marvel tried to stay on

board with the horror genre but, based on the

experience with Tower of Shadows and Chamber

of Darkness, decided to go for reprint

titles only,

mostly

sourced from 1950s and very early 1960s issues of

Journey into Mystery, Strange Tales, Tales to

Astonish and Tales of Suspense.

However, success was still limited and, in

comparison to DC's figures, meagre: With only 38

issues under its belt, Where Monsters Dwell

(launched in January 1970) became the

longest running Marvel anthology reprint title

before being dropped in October 1975.

It would take Marvel a

moment to figure out how to make the horror genre

work for its readership, and the answer would be

the "superhero from the crypt" in the

shapes and forms of Ghost Rider, Werewolf by

Night and Tomb of Dracula as well as black &

white magazines.

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

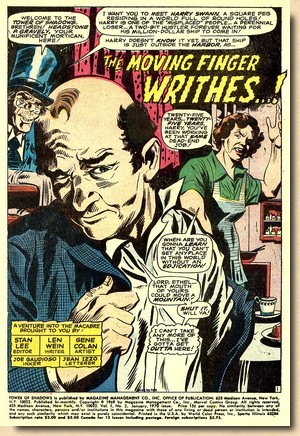

|

Editor -

Stan

Lee

Cover

pencils - Marie

Severin

Cover inks -

Frank

Giacoia

"The

Moving Finger Writhes...!"

(7

pages)

Story

- Len Wein

Art - Gene Colan

Inks - Mike Esposito (as

Joe Gaudioso)

Lettering -

Jean

Izzo, Morrie

Kuramoto

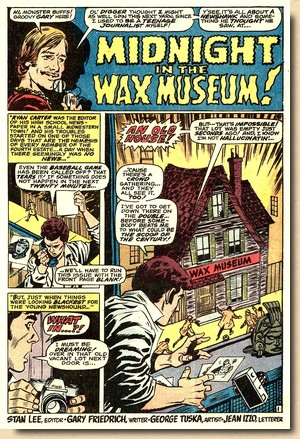

"Midnight

in the Wax Museum!"

(7

pages)

Story

-Gary Friedrich

Art & Inks - George

Tuska *

Lettering -

Jean

Izzo

*

Gary

Friedrich caricature and parts of

page 3 by Marie Severin

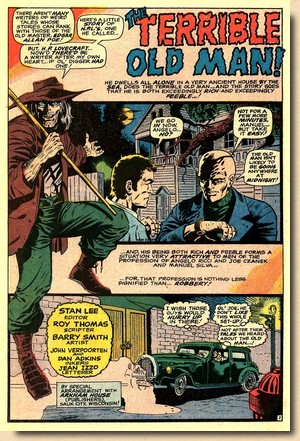

"The

Terrible Old Man!"

(7

pages)

Story

- Roy Thomas

(adapted from a story by H. P.

Lovecraft)

Art - Barry Windsor-Smith

Inks - Dan Adkins,

Joe Verpoorten

Lettering -

Jean

Izzo

|

|

|

| |

| Tower of Shadows

#3, cover dated January 1970, went on sale 21

October 1969. For the 15¢ buyers plopped down in

those days, they still got a total of 21 story

pages - in this case divided up evenly over the

three stories, all of which was original

material, i.e. brand new.

Both the writing and artwork were

provided by established as well as new talent:

Roy Thomas, George Tuska and Gene Colan were

joined by relative newcomers Gary Friedrich (who

had started out at Marvel in 1967 writing Western

material), Len Wein (this being his very first

story for Marvel after some previous work for DC)

and Barry Windsor-Smith (whose first work for

Marvel was X-Men #53 in late 1968),

while Jean Izzo (the daughter of long-time Marvel

letterer Artie Simek) had started lettering for

Marvel in 1967.

While "The Terrible Old Man" is an

authorised adaptation by Roy Thomas of the

identically titled short story by H. P. Lovecraft

(originally published in 1921 and part of the

Cthulhu mythos), the other two entries "The

Moving Finger Writhes...!" and

"Midnight in the Wax Museum!" employ

similarly classic horror plots and twists.

|

| |

|

| |

| In "The Moving Finger Writhes...!"

a certain Harry Swann, constantly berated by his

wife for working at a dead end job, finds and

buys a book entitled The Life and Times of

Harry Swann at a rare books shop. Shockingly,

it is a literal transcription of his entire

life's history, but Harry soon discovers that

some chapters pertain to events that have yet to

take place, and following these he turns his

fortune around by making a fortune placing bets

at the racetrack on horses that he knows will

win. But even with this newly found wealth his

wife keeps nagging, so Harry again follows the

book and tampers with the brakes of his wife's

car, who then dies in an accident. On his way

back from the funeral, Harry is held up due to

some construction work and, in order to pass the

time, skims through the book again - but

confusingly, the pages are now blank. It is at

this moment that a falling iron beam crushes him

to death. One of the work men at the site,

Charlie Jenkins, picks up the book when he

realizes that the cover reads The Life and

Times of Charlie Jenkins. Curious about his

strange new discovery, he wanders off and begins

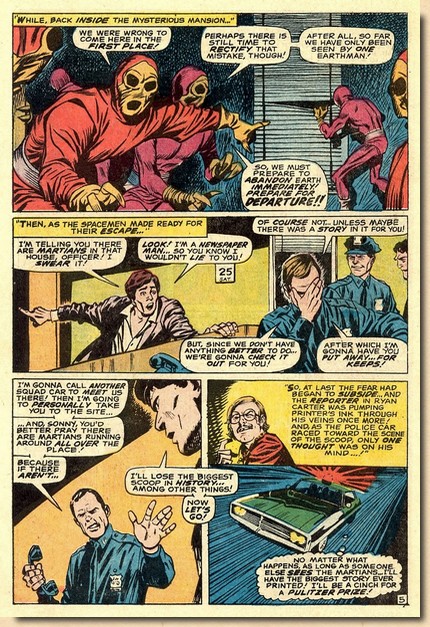

reading the book... Somewhat less elaborate,

"Midnight in the Wax Museum!" tells the

story of an ambitious reporter who witnesses

strange events in conjunction with an alien

landing, but of course nobody believes him and he

ends up being considered out of his mind. What

does set this little tale apart from the two

others is the fact that the narrator isn't

Headstone A. Gravely or Digger, but rather

"Groovy Gary" - that is to say Gary

Friedrich, the author of this yarn.

|

| |

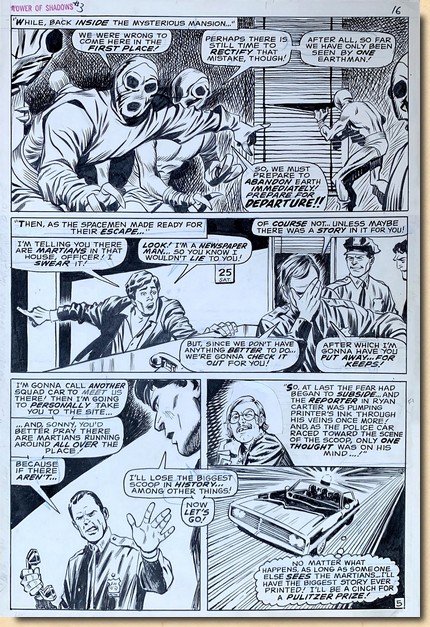

Original

artwork by George Tuska (pencils and

inks) for page 5 of "Midnight in the Wax

Museum!" from Tower Of

Shadows #3 (scanned from the original),

and the same page as it appeared in

print.

|

|

| |

| In a way, it

was a natural chain of thought for Marvel - if

you are talking to the readers and introducing

stories, why use fictional characters when you

could just as well feature the individuals who

actually produced the story? |

| |

|

Not

surprisingly, it started with

"Smilin'" Stan Lee

himself as host and narrator for

Roy Thomas' adaptation of Edgar

Allan Poe's short story The Masque of

the Red Death in

Chamber

of Darkness #2 (December 1969).

The idea

caught on in a flash, with Gary

Friedrich being the second in

line here but by no means the

last (other such cameos included artists Don Heck

and Gene Colan in Tower of

Shadows #4, Tom Sutton

in Chamber

of Darkness #4, Roy Thomas and

Tom Palmer in Tower of

Shadows #9 , and Bill

Everett and Dan Adkins in

Chamber

of Darkness #8).

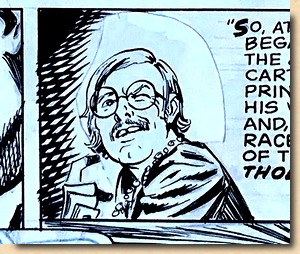

However,

a closer look at the original

artwork reveals that having Stan

Lee and Garry Friedrich as hosts

was an afterthought, coming late

in the production process of Chamber

of Darkness #2 - the artwork

was already fully lettered and

inked when the idea popped up.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Stan Lee as host in Chamber

of Darkness #2 (December

1969), scanned from the original

artwork

|

|

As a result,

paste-ups were used over the

already completed artwork. In the

case of

Chamber

of Darkness #2, Don Heck's

original image of Headstone A.

Gravely was covered by a stat of

a portrait of Stan Lee by Marie

Severin, whose many talents

included drawing amazing

caricatures of virtually every

Marvel staffer to ever have set

foot in the Bullpen.

In

addition, the already finished

lettering in the word balloons

was covered and corrected in

places to fit the new host - all

of which is quite evident on the

original artwork. The

inspirational source for the

drawing of Lee himself quite

clearly seems to be a well-known

official 1968 photograph, right

down to the tie Lee is wearing.

The

original artwork for Tower of

Shadows #3 reveals a similar

process, where the head of Gary

Friedrich (again the work of

Marie Severin) has been pasted

onto the host originally drawn by

George Tuska.

Stan

Lee, of course, loved to play

around with the fictional reality

of a comic book story and the

real world. A prime example is

his self-portrayal in his

real-life job as a comic book

editor caught up in a fictional

encounter with what is a very

thinly veiled real-life Dr

Wertham in Suspense #29

(April 1953). And of course the

same principles apply when Stan

Lee and Jack Kirby - portrayed as

comic book writer and artist

within a comic book they actually

wrote and pencilled - are visited

by none other than Dr Doom in Fantastic

Four #10 (January 1963) or

are both refused entry to Reed

Richards and Sue Storm's wedding

in Fantastic Four Annual

#3 (December 1965).

|

|

|

| |

| So was it Lee's idea to feature himself as

the host of a story in an anthology horror title,

followed by further writers and artists in

subsequent issues of Tower Of Shadows

and Chamber Of Darkness? The answer may

be lost to comic book history, but it certainly

was, as they say, a

nice idea that certainly made for the perfect

icing on what was already quite an exquisite

cake. Unfortunately, it did not turn out to be

the flavour of the day. Tower Of

Shadows also sported a letters page (aptly

named "Tomes from the Tower!"), and on

this occasion, editorial was keen to point out

that Marvel had not nicked the idea of having a

host from rival DC (as one reader insinuated) but

that the concept went back to the classic EC

comics.

|

| |

Other

than that, Tower Of Shadows #3

included the usual fan-loved fare in the

form of in-house ads (such as promoting

the latest Avengers and Thor

issues as "2 more Triumphs from

Marvel") as well as the Bullpen

Bulletin (titled "A Sagacious

Smattering of Somewhat Senseless

Small-Talk!" this time around) and

the Mighty Marvel Checklist (which on

this occasion actually mentioned Tower

Of Shadows #3).

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|