|

|

|

TARZAN,

BATMAN & SUPERMAN

BACK

TO BACK IN A

JANUARY

1973 DC SUPER PAC

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

DC COMICS

SUPER-PACs |

|

Even in the early

1960s, the comic book industry

realized that in spite of the

hugely successful comeback of the

superhero genre (which had been

clinically dead for most of the

1950s) and the subsequent streak

of new creativity and enthusiasm

it generated, its traditional

sales points were fading away.

Small stores that had carried

comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and

supermarkets, and newsagents

started to view the low

cover prices and therefore tiny

profit margins comics had to

offer as a

nuisance. Many ideas on how

to turn these developments around

were put forward by different

publishers, but the most

successful concepts strived to

open up new sales opportunities

and markets and thus tap into a

new customer base.

|

|

|

|

| |

| One place

these potential buyers could be found was the growing

number of supermarkets and chain stores. But in order to

be able to sell comic books at supermarkets, the product

would have to be adjusted. |

| |

| Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Outlets were even supplied with dedicated Comicpac

racks, which enhanced the product appeal even more since

the bags containing the comic books could be displayed

on rack hooks in an orderly and neat fashion. It didn't really matter therefore

that buying these three comic books in a comicpack for

say 59¢ (rather than from a newsagent for 60¢ in that case) clearly presented no real bargain - it

was the opportunity and convenience to pick up a few

comics at the same time parents and adults did their

general shopping. Neatly packaged, it almost became an

entirely different class of commodity. DC's

"comicpacks" were, in a word, a success - so

much so that other publishers quickly started to copy it.

|

| |

|

|

"The

DC [comic packs] program lasted well

over a decade, with pretty high

distribution numbers. The Western

program was enormous - even well into

the '70s they were taking very large

numbers of DC titles for distribution

(I recall 50,000+ copies

offhand)." (Paul Levitz, in

Evanier 2007)

By the early

1970s, DC relaunched their comicpacs,

calling them DC Super Pacs, and

they continued to sell well.

Unlike comic books

distributed to news stands and other

traditional outlets, comicpacks were

non-returnable. Bags that didn't sell

were thus the retailer's problem, not the

publisher's (leading some distributors

and retailers - who most likely had

previously rigged the returnable comic

scheme, e.g. by selling comic books

without their covers - to simply split

the packs open and return the loose

comics).

|

|

|

| |

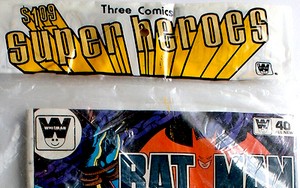

| The only way to stop such illegal

behaviour was to make comic books contained in

comic packs distinguishable from regular news

stand editions - and Western, the largest

distributor of comic packs, did just that as of

1972 by introducing their logo on the cover. DC titles distributed by

Western in their own comicpacks featured the

Western "smiling face" logo instead of

the DC roundel; the covers would also not show

the issue number and the month.

DC's own comicpacks,

however, continued to contain regular newsstand

editions only throughout the 1970s.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

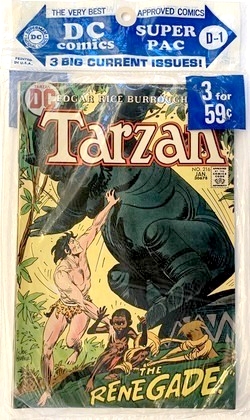

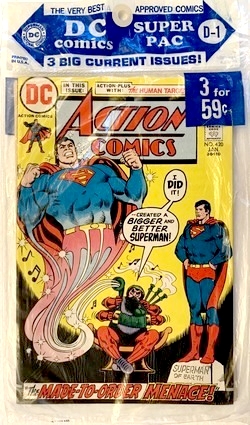

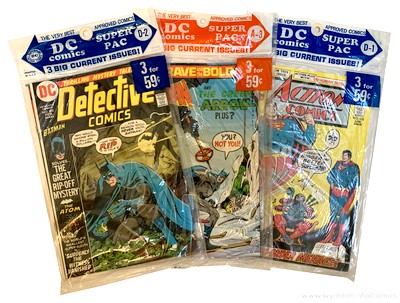

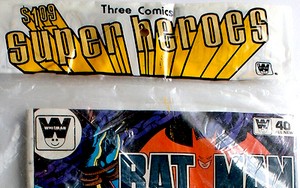

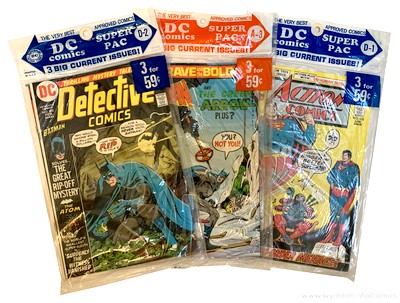

| This January (D-1) 1973 DC SUPER PAC

contains Tarzan #216, Detective Comics #431,

and Action Comics #420. and features two

flagship DC characters (Superman and Batman) alongside

one of DC's major licensed title (Tarzan). Right from the start in 1961/62, when DC

Comics launched the Comicpac, all of their

multi-comic packs were reference-numbered using a letter

plus digit, e.g. B-3. And since DC wasn't just filling

plastic bags at random with any comic books, a B-3 pack

from a specific year would carry the same titles and

issues no matter where or when it was sold (rare

packaging errors aside). By 1964 the digit would refer to

the month and contain comic books with a January cover

date (or January/February in the case of bi-monthly

titles), and the letters (A through D) marked the four

different packs per month (which was the rule from

mid-1972 to 1978, when DC ended their own comicpacks).

"D-1" therefore denotes the fourth January

SUPER PAC, in this case from 1973.

|

| |

| No titles had truly

permanent slots in the SUPER PACS, although there was a

high level of consistency with DC's flagship characters

(the data for 1973, for example, shows that the

SUPER PACs of that year offered buyers complete runs of Superman

and Batman as well as the Batman team-up title Brave

and the Bold). But since

sales points could vary a lot with regard to their

supplies and selection of SUPER PACs, the availability of

specific titles was never guaranteed. However, one needs to bear in mind that

this was a common fate of the average comic book reader

in the 1970s Bronze Age, whether his or her comic books

came packaged in a plastic bag or as single issues from a

display or spinner rack. Back in those days, an

uninterrupted supply of specific titles was, quite

simply, never truly guaranteed. In the case of DC titles this mostly

wasn't a problem anyway. Unlike their major competitor

Marvel, DC's editorial at large still very much embraced

the "single issue, done in one" storyline

principle during the early 1970s, so it often didn't even

matter in which sequence you read your copies of Batman

or Superman, since every issue would start with

a brand new story (there were, of course, exceptions).

Also very much unlike Marvel,

DC had no regular editorial feature across its titles at

the time, through which the publisher would communicate

with its readership (the way Marvel and Stan Lee did with

their famous Bullpen Bulletins); the interaction

with fans and readers was limited to the letters pages,

and plugs for other titles restricted to in-house ads.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

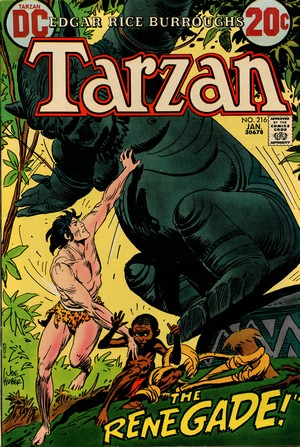

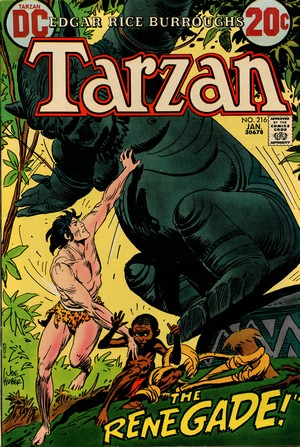

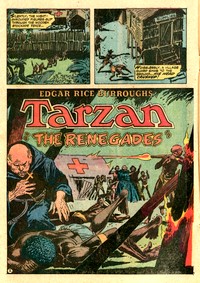

TARZAN

#216

January 1973

(monthly)

On Sale: 28 November 1972

Editor

- Joe Kubert

Cover - Joe Kubert (pencils & inks)

"The Renegades"

(18 pages)

Story - Joe

Kubert

Pencils -Frank Thorne

Inks - Joe Kubert

Lettering -

John Costanza

Colouring - Tatjana Wood

PLOT SUMMARY - Tarzan

prevents the looting of an ancient temple

by a group of renegade mercenaries.

|

|

|

| |

| Tarzan, created by American writer Edgar Rice

Burroughs in 1912 for a story entitled Tarzan of the

Apes, was an immediate hit with the pulp fiction

readership (Burroughs himself wrote two dozen sequels),

quickly became the star of radio shows, movies and other

media, and has been a household name in popular culture

ever since (Lupoff, 2005). Tarzan's career in comics

started out with an adaptation of Tarzan of the Apes into

newspaper strip form in January 1929, with artwork by Hal

Foster (of "Prince Valiant" fame). Numerous

publishers subsequently put out Tarzan comic books, and

the character has been licensed by Gold Key (Western

Publishing), Charlton, DC, Marvel, and Dark Horse Comics

over the decades.

|

| |

| DC took over the series in April

1972, publishing 52 issues of Tarzan up until

February 1977, and continued the numbering from

the previous Gold Key series, thus strating out

with Tarzan #207 and ending in Tarzan

#258 (publishers in the early 1970s still

believed that a comic book series would sell less

if people perceived it as new). It seems the main reason

Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. chose to transfer the

comic-book license for Tarzan was Western's

disinterest in stepping up its production; Gold

Key was only putting out eight issues of Tarzan

a year (along with six issues of Korak,

Tarzan’s son), but none at all starring any of

Burroughs’ other creations, in spite of an ever

increasing market interest for more of his

material both in the US and abroad (Stewart,

2022). A chance meeting in Europe between Carmine

Infantino and ERB Inc.'s vice-president Robert

Hodes sealed the deal with DC (Schelly, 2008).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Infantino, it seems, had thought

of Kubert (who had enjoyed Burroughs’ fiction and Hal

Foster’s work on the newspaper comic strip in his

youth) right from the get-go of acquiring the license. |

| |

Carmine

Infantino

(1925 - 2013)

|

|

"One bright,

sunny day, Carmine called me into his office.

“Joe” he said with a broad smile, “how

would you like to do Tarzan?” Carmine and I

had known each other since we started in this

business. If anyone knew of my love for

Burroughs’ Tarzan, he did. I jumped at it.

Here was an opportunity for me to connect

again with the joys of my childhood. To

infuse myself into the world of Tarzan, the

Ape-Man, and to write and draw the character

that had been an inspiration to me." (Kubert,

2005)

Kubert immediately and

enthusiastically geared up for what he considered

to be a dream project, and his enthusiasm for the

material resulted in what is considered by many

to be some of the best work of his long career.

|

|

Joe

Kubert

(1926 - 2012)

|

|

| |

| Kubert decided to start out at

the beginning and thus initiated DC's run with an

adaptation of Burroughs’ first Tarzan novel. Whilst

this had been done before (by Hal Foster in a newspaper

strip rendering in 1928 and by God Key in a single issue

adaptation in 1965), editor-writer-artist Kubert wanted

this to go deeper into the original material, resulting

in a four-issues arc in Tarzan #207-210. |

| |

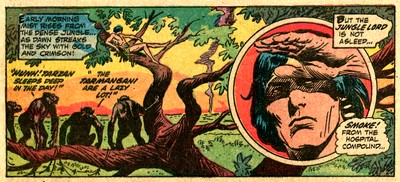

Tarzan

#216

|

|

DC's Tarzan

would feature additional adaptations of

the Burroughs books, with original

stories by Kubert slotted in between. Tarzan #216

stands out somewhat, as Frank Thorne took

over pencilling duties, albeit inked by

Kubert (who resumed complete art

responsibility with the following issue).

Critically

acclaimed, Kubert's take on Tarzan had

its critics at the time, as can be

glanced from the letters pages - although

more than anything else, it was the

backup feature that drew its regular flak

from readers who essentially just wanted

to see Tarzan in a comic book carrying

the title Tarzan.

|

|

|

| |

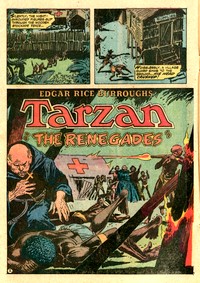

"Beyond

The Farthest Star"

(6 pages)

Story - Marv Wolfman

Pencils -Howard Chaykin

Inks - Howard Chaykin

Based on the

two novellas Adventure on Poloda

(published in 1942) and Tangor Returns

(published in 1964), which Burroughs had written

in a very short time in late 1940, they formed

the nucleus for a series that never came to be

and therefore remained a much lesser known part

of Burrough's work.

Marv Wolfman

breathed new life into it by adapting it for the

backup slot in DC's Tarzan, where it ran

through issues #212-218 (September 1972 - March

1973) as well as in Tarzan Family #61

(February 1976).

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

DC's very

first issue featuring the

character, Tarzan #207,

was included in the April 1972

B-4 DC Super Pac, and at least

three more issues are known to

have been included in Super Pacs

prior to Tarzan #216,

the tenth issue produced by DC. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

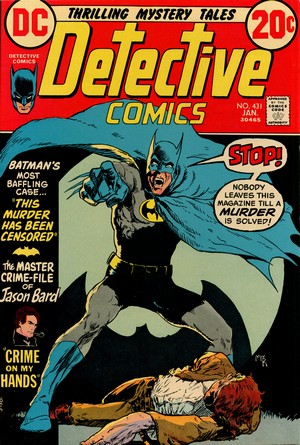

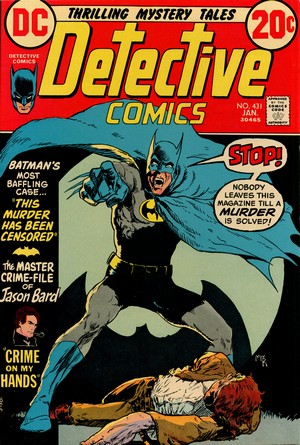

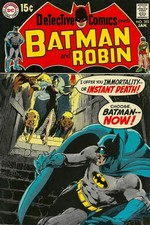

DETECTIVE

COMICS #431

January

1973

(monthly)

On Sale: 30 November 1972

Editor - Julius

Schwartz

Cover - Michael Kaluta (pencils

& inks)

BATMAN:

"This Murder Has Been

Censored"

(14.5

pages)

Story

- Denny O'Neil

Pencils - Irv Novick

Inks - Murphy Anderson

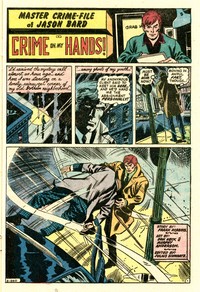

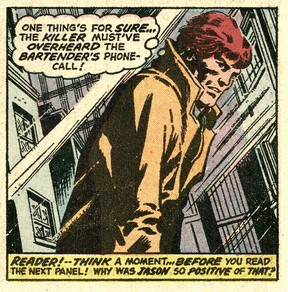

JASON

BARD: "Crime On My

Hands!"

(9

pages)

Story

- Frank Robbins

Pencils - Don Heck

Inks - Murphy Anderson

PLOT

SUMMARIES

- Batman investigates and solves

a murder at a luxury resort when

a man with the word

"censored" stamped on

his forehead is found dead. Jason

Bard finds one of his business

cards with a message scribbled on

it on a dead bartender.

|

|

|

|

| |

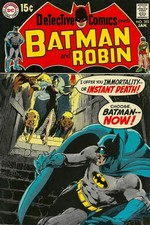

| It all started on November 26th

1969, when Detective Comics #395 hit the

newsstands with a cover date of January 1970. On the

surface of things, it was the first issue of DC's

namesake flagship title written by Dennis O'Neil and

drawn by Neal Adams. But at the core, Batman was about to

change in a fundamental way that would shape the

character indelibly. The story,

"The Secret of the Waiting Graves", is now a

classic in itself and often considered to be Batman’s

turning point as the Silver Age crossed into the Bronze

Age and the Darknight Detective returned to his gothic

roots.

|

| |

Dennis

"Denny" O'Neil

(1939 - 2020)

|

|

In actual fact, other writers and

artists were already taking Batman down that path

at that time, but O'Neil's chilling tale pointed

out the potential of the Caped Crusader as a

truly dramatic character like possibly no other

story previously had. It was a compelling concept

that hit home with readers and Batman editor

Julie Schwartz alike, and over the next few

years, the best was yet to come - not the least

because O'Neil had a clear-cut plan.

"The comics

at the time had been trying to follow the

example of the Adam West comedic TV show, and

they weren’t doing a very good job of it

(...) The books were being a bit shaky

sales-wise, as hard as that is to believe,

and Julie [Schwartz] wanted to continue to

publish Batman. So he came to me and asked,

“What have you got my boy?” What I

thought I had, and what I told people I had,

was that we were going back to what Bill

Finger started with in 1939, and we added to

that what the world had learned about telling

stories since then." (O'Neil, in

Handziuk 2019)

|

|

Detective

Comics #395

(January 1970)

|

|

| |

O'Neil was very methodical about

his take on turning the Batman into a much grimmer, darker character

"I went to

the DC library and read some of the early

stories. I tried to get a sense of what Kane

and Finger were after." (O'Neil, in

Pearson & Uricchio 1991)

Ultimately,

this also resulted in underscoring the

investigative side of the Batman's persona -

effectively creating the Darknight Detective.

"There was

very little consistency. Sometimes he was a

detective, sometimes he was more a superhero.

When I took over the franchise I said okay,

this is the way we do it. Batman comics will

be about superhero stuff with a lot of

action, and Detective Comics is about the

same character functioning as a

detective." (O'Neil, in Handziuk

2019)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

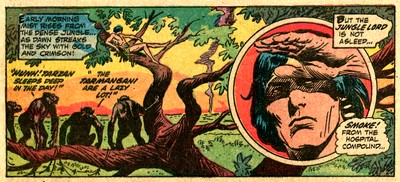

| As a result, Batman and Detective

Comics took two entirely different routes. The most

obvious change for the latter title was the complete

disappearance of costumed villains, all of which were

replaced by plain clothes thugs and evil-doers. |

| |

|

|

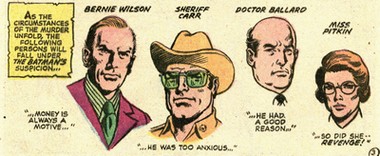

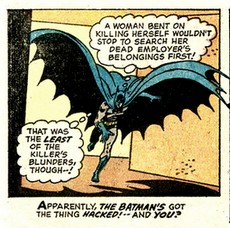

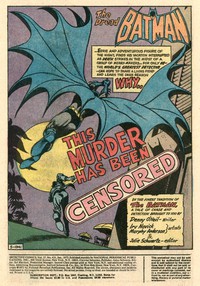

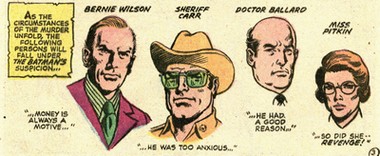

Detective

Comics #431 is a prime

example of this approach, which

also tried to involve readers in

the puzzle solving process -

matching wits and detection

skills, so to speak, with the

Batman. And like any good novel

from the 1930's Golden Age of

crime fiction by the likes of

Agatha Christie, readers of Detective

Comics #431 were not only

presented with a line-up of the

characters involved but also

given a handy overview of what

their potential motives would be

for them to become suspects as

Batman would unravel and solve

the mystery surrounding the

murder. |

|

|

|

| |

| The classic Michael Kaluta

cover for Detective Comics #431 emphasizes the

frequent nods to literary works of classic detective

fiction, with Batman directly adressing the reader and

declaring, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, "STOP!

NOBODY LEAVES THIS MAGAZINE TILL A MURDER IS

SOLVED!" |

| |

The detective

approach also involved O'Neil

dropping hints that a certain

aspect presented in the text or

(more frequently) depicted in the

artwork contained a vital clue,

as well as showing Batman putting

the bits and pieces together in

his musings and thoughts.

|

|

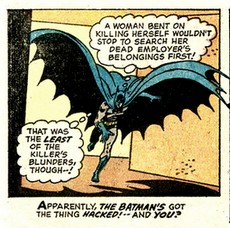

This

also lead to one or more

instances every issue

where readers were

essentially asked to

pause and consider the

possible solution to the

mystery tale they were

reading - in this case

even prodded by the

remark that "apparently

the Batman's got the

thing hacked! -- And

you?". It

made for great reader

involvement, and the

letters pages at the time

were proof of the fact

that it was appreciated

and savoured. It thus

also made total sense to

haver the cover tag-line "Thrilling

Mystery Tales".

The back-up feature in

Detective Comics

would change frequently

during that period, but

Jason Bard certainly was

a very fitting

accompaniment.

|

Following

his first appearance in Detective

Comics #392 (October 1969),

the stories featuring the Gotham

private investigator worked

exactly the same way - and Frank

Robbins was every bit a master at

this for his own creation Jason

Bard as Denny O'Neil was for the

Batman.

It

distinctly set apart Detective

Comics from other comic book

titles - a special tidbit of

reading thrill. And just like the

aformenetioned crime writers of

the 1930s and 1940s, the stories

and mysteries were played

"fair" - the clues

could indeed be spotted, so in

essence the readers always had

the same knowledge as the

protagonists did.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Detective

Comics was a regular title

in DC's SUPER PACs - six out of

the twelve issues published in 1973 were offered in

DC's Super-Pacs. The

endpage of the Batman story of Detective

Comics #431 featured a half-page ad for Shazam

#1, which would

also be packaged into the B-2

February 1973 Super-Pac.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

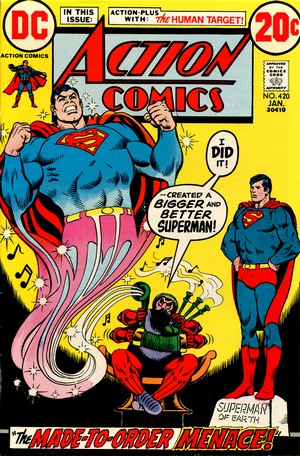

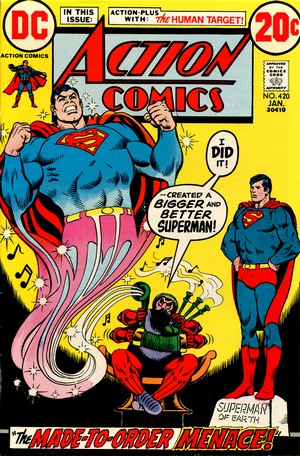

ACTION

COMICS #420

January

1973

(monthly)

On Sale: 30 November 1972

Editor - Julius

Schwartz, E. Nelson Bridwell

(assistant)

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

SUPERMAN:

"The

Made-To-Order Menace!" (15

pages)

Story

- Elliot Maggin

Pencils - Curt Swan

Inks - Murphy Anderson

HUMAN

TARGET: "The

King of the

Jungle-Contract!" (8.66

pages)

Story

- Len Wein

Pencils - Dick Giordano

Inks - Dick Giordano

PLOT

SUMMARIES - A

space-travelling bard who has the

power to create what he sings

about comes to Earth and creates

a super-menace for Superman to

battle. The Human Target is hired

by a famous big game hunter who

believes that his rival is trying

to kill him and goes on a safari

in Africa disguised as his

client.

|

|

|

|

| |

| When Action Comics #420

hit the newsstands (and the 1973 D-1 Super-Pac),

the Man of Steel's adventures were regularly in

the hands of writer Elliott (S!) Maggin. Born in

1950 and thus only 22 years of age, he had only

started out twelve months prior, albeit with a

bang - his first script appeared in Superman #247

(January 1972), titled "Must There Be A

Superman?", and gained almost instant

classic status. Maggin was

Instantly considered a prodigy by editor Julie

Schwartz who liked his approach, which was deeply

rooted in classic mythology.

"I had

written a paper for a humanities class

comparing Superman to Achilles, talking about

the classical themes that recur in the

literature of archetypal characters. I think

there's something hard-wired in the human

brain that causes us to suck up stories of

that sort and make them a permanent part of

our consciousness." (Maggin, in

Freiman 2009)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

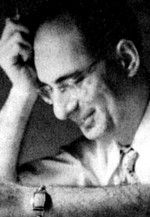

| And so, Maggin (who would go on

to sign his name as Elliott S! Maggin, the exclamation

mark being a reference to the abundant use made of it in

comic books) was offered the opportunity to write scripts

for Superman (Freiman, 2009). |

| |

Elliott Maggin

|

|

"I

was in the right place at the right

time, certainly, because I fell into

place at a time when Superman was

kind of out of fashion among comics

mavens. When Mort Weisinger retired

and Julie took over Superman I don’t

think anyone knew quite what to do

with the character. Mort’s

approach had been that he was telling

fairy tales for children. When I

showed up with this classic liberal

education, I brought this notion that

Superman was a contemporary icon and

had to reinterpret that iconography

in twentieth-century terms." (Maggin,

in Stroud 2018)

Paired with Maggin

for the artwork were classic Superman

creative talents Curt Swan (pencils) and

Murphy Anderson (inks), both of which

produced work that not only conformed to

the DC house but in many ways shaped it.

"DC

artists were forced to work within an

established house style that governed

the page layout as well as the look

of the artwork. Editor Julie

Schwartz's motto was 'if it's not

clean, it's worthless'."

(Tucker, 2017)

|

|

|

LenWein

(1948-2017)

|

|

Private investigator and

bodyguard Christopher Chance - who assumes the

identities of clients targeted by assassins and

other dangerous criminals and thus goes by the

moniker of Human Target - was created by Len Wein

and Carmine Infantino and made his first

appearance only a month prior to this outing, in Action

Comics #419 (December 1972). The character would continue

to be the back-up feature in several issues of Action

Comics up until issue #432 (February 1974)

before moving to the Batman titles Brave and

the Bold and Detective Comics. In

2010, the Human Target was turned into a Fox TV

series that lasted for two seasons.

"The only

thing I owed my audience was my own judgment

and my own best effort. I write my stories

for me and hope that other people will like

them as well." (Wein, in Wolfman

AN)

|

|

|

|

| Julius Schwartz had only taken

over the editorial reigns of Action Comics with the previous

issue, and he wasn't happy at all with its main

character, the Man of Steel. |

"Having spent

much of the previous decade merely observing

from the cultural sidelines, the

now-thirtysomething Superman was hit hard by

the disillusionment that seized the country

in the 1970s (...) Marvel heroes bickered and

questioned and agitated - they were agents of

chaos, and they looked like the kids who read

them. Superman, on the other hand, dutifully

imposed order, and he looked like a

cop." (Weldon, 2013)

And Schwartz wasn't alone

in feeling that the character had somewhat fallen

out of sync with the times.

"O'Neil

shared his editor's ambivalence, because he

figured that such a high-profile character

would come with too many corporate strings

attached. He also found it difficult to get

excited about a character who could see

through time and blow out a star. "How

do you write stories about a guy who can

destroy a galaxy by listening hard?"

O'Neil famously joked." (Weldon,

2013)

Together, Schwartz and

O'Neil reached the conclusion that the only way

forward was to "depower" Superman -

readers needed to see him struggle.

|

|

Julius

Schwartz

(1915 - 2004)

|

|

| |

| And so, they took the man of

Steel's well-known major weakness off the board as all

Kryptonite on Earth was turned into iron by a freak

scientific experiment in Superman #233 (January

1971). At the same time, Superman's powers started to

mysteriously fade. |

| |

|

|

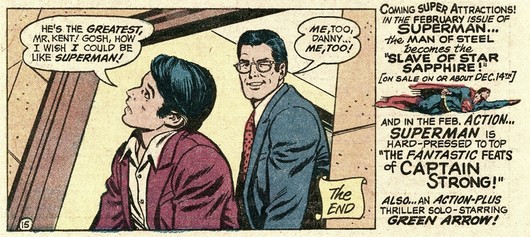

It was a nice

idea, but there simply were too many

"super-this" and "super-that"

abilities tied into Superman as a character, and

Clark Kent was still constantly having to foil

the discovery of his dual identity. At the end of

the day, not too much changed after all - except

O'Neil didn't want to write Superman anymore

(Freiman, 2009). The most problematic aspect,

however, were the villains: far fetched,

convoluted, and ultimately uninteresting. The

Space Minstrel is just as much an example of this

as are Star

Sapphire and Captain Strong.

|

|

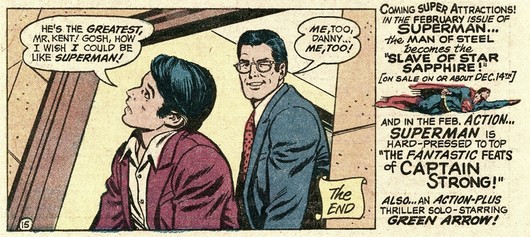

| |

| Unless you were a die-hard

Superman fan, a lot of those stories didn't really seem

to go anywhere relevant. Not surprisingly, many readers

bought Action Comics not because they were fans

of Superman, but because of the second features appearing

in the title (Kingman, 2013). |

| |

|

| |

|

|

Action

Comics #419 (featuring the

first appearance of Human Target)

was packaged into the D-12

December 1972 Super-Pac . |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| DC back in the early 1970s was

often trying hard to be just as cool as competitor

Marvel, but somehow it rarely worked - as can be glimpsed

from the in-house ads of the time, which both in terms of

verbage and visuals is hardly making a splash and seems

very matter-of-fact. |

| |

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

| EVANIER Mark (2007) "More

on Comicpacs", News From Me,

published online 2 May 2007 FREIMAN Barry

M. (2009) "Exclusive

Interview with Elliot S! Maggin", supermanhomepage.com,

published online January 2009

HANDZIUK Alex

(2019) "An

Interview with Legendary Creator Denny O'Neil -

The father of Modern Day Batman", cgmagonline.com,

published online 16 March 2019

KINGMAN

Jim (2013) "The Ballad of Ollie and

Dinah", in Back Issue #64 (May

2013)

KUBERT

Joe (2005) "Introduction", Edgar

Rice Burroughs’ Tarzan: The Joe Kubert Years,

Dark Horse Books

LUPOFF

Richard A. (2005) Master of Adventure:

The Worlds of Edgar Rice Burroughs,

University of Nebraska Press

PEARSON

Roberta E. & William Uricchio (1991)

"Notes from the Batcave: An Interview with

Dennis O'Neil", in The Many Lives of the

Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and

His Media, Routledge

SCHELLY

Bill (2008) Man of Rock: A Biography of Joe

Kubert, Fantagraphics Books

STEWART

Alan (2022) "Tarzan

#207 (April, 1972)", Attack Of The

50 Year Old Comics, published online 26

February 2022

STROUD

Bryan (2018) "An

Interview With Elliot S! Maggin - A Superman

Author Worthy of the S!", nerdteam30.com,

published online 20 June 2018

TUCKER

Reed (2017) Slugfest: Inside the Epic

Fifty-Year Battle between Marvel and DC,

Sphere

WELDON

Glen (2013) "The

70s Were Awkward for Superman", The

Atantic, 3 April 2013

WOLFMAN

Marv (AN) "Speaking

with Len Wein Part One", What Th--?

Exclamations from The Wolfmanor, published

online, date unknown

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2023

uploaded to the web 9 June

2023

|

| |

|

| |

|