|

|

|

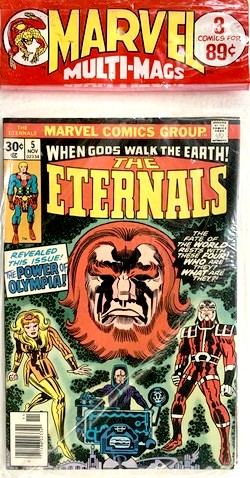

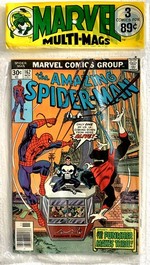

THE

ETERNALS, SHANG-CHI &

SPIDER-MAN

BACK

TO BACK IN A

NOVEMBER

1976 MARVEL MULTI-MAGS

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

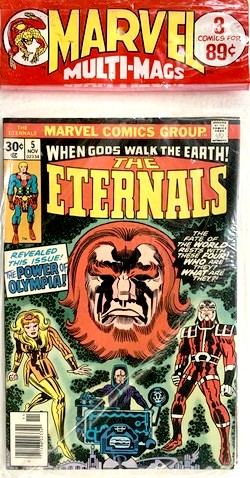

ETERNALS #5

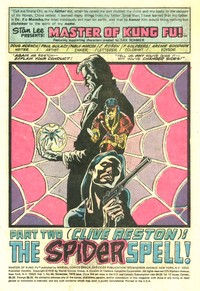

MASTER OF KUNG

FU #46

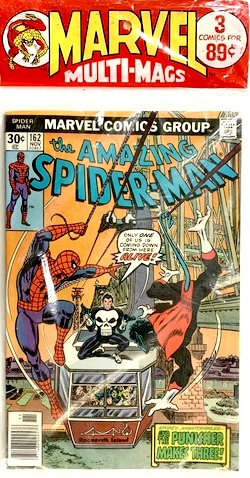

AMAZING

SPIDER-MAN #162

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

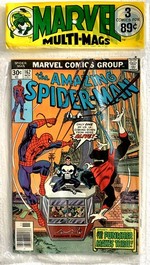

MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS |

|

Even in the early

1960s, the comic book industry

realized that in spite of the

hugely successful comeback of the

superhero genre (which had been

clinically dead for most of the

1950s) and the subsequent streak

of new creativity and enthusiasm

it generated, its traditional

sales points were fading away.

Small stores that had carried

comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and

supermarkets, and newsagents

started to view the low

cover prices and therefore tiny

profit margins comics had to

offer as a

nuisance. Many ideas on how

to turn these developments around

were put forward by different

publishers, but the most

successful concepts strived to

open up new sales opportunities

and markets and thus tap into a

new customer base.

|

|

|

|

| |

| One place

these potential buyers could be found was the growing

number of supermarkets and chain stores. But in order to

be able to sell comic books at supermarkets, the product

would have to be adjusted. |

| |

| Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Outlets were even supplied with

dedicated Comicpac racks, which enhanced the

product appeal even more since the bags containing the

comic books could be displayed

on rack hooks in an orderly and neat fashion. |

| |

|

|

DC's

pioneer "comicpacks" were a

success - so much so that other

publishers quickly started to copy it.

Marvel produced a series of Marvel

Multi-Mags in 1968/69 but then seems

to have dropped the idea again.

However, by the

mid-1970s, the House of Ideas had

once again fully embraced the marketing

concept of selling multiple comic books

packaged in a sealed plastic bag to a

customer base which comic books could

hardly reach otherwise: people shopping

at supermarkets and large grocery stores.

It didn't really

matter therefore that buying these three

comic books in a comicpack for say 89¢

(rather than from a newsagent for 90¢ in that case) clearly presented no

real bargain - it was the opportunity and

convenience to pick up a few comics at

the same time parents and adults did

their general shopping.

Neatly packaged, it

almost became an entirely different class

of commodity.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| The comic books contained in this

specific MARVEL MULTI-MAGS are all

from the November 1976 cover date run, which meant that

they were actually on sale at newsagents in August 1976 -

although there could be quite a delay in terms of actual

availability of MARVEL MULTI-MAGS

at some sales points, resulting in Multi-Mags on display

that contained "semi-recent books (typically

about nine months old)" (Brevoort, 2007).

Considering the packaging and distribution process, this

doesn't really seem too surprising. |

| |

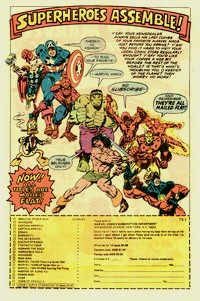

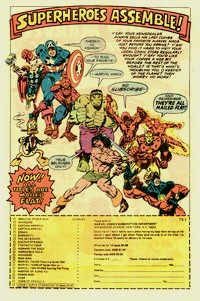

| No titles had

permanent slots in the MARVEL MULTI-MAGS, but both Amazing Spider-Man and Eternals

would show up in a reliably regular way. Issues

of Master of Kung Fu, on the other hand, have only featured in three

of the 250 MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS known

to date. But even with the

fairly regular titles (other examples were Hulk,

Avengers and Fantastic Four) there was

never any guarantee of an uninterrupted flow of

consecutive issues - and therefore a distinct possibility

of missing out on a part of the storyline. On top of

this, the continuity of the Marvel Universe of the 1970s

was such that plots and storylines usually evolved over

more than one issue. This didn't exactly make the MULTI-MAGS an ideal way of getting your

Marvel comic book fix. On

the other hand, this was a common fate of the average

comic book reader in the 1970s, whether his or her comic

books came packaged in a plastic bag or as single issues

from a display or spinner rack. Back in those days, an

uninterrupted supply of specific titles was, quite

simply, not guaranteed. Not worrying too much about

possible gaps in storylines thus became something of a

routine - besides, you would usually get a recap of

"what happened so far" on the first page.

So all in

all it simply was a part of being a comic book fan in the

1970s - as were the monthly Bullpen Bulletins (which were

the responsibility of the editor-in-chief) and the

in-house advertising.

|

| |

|

|

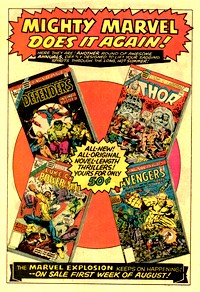

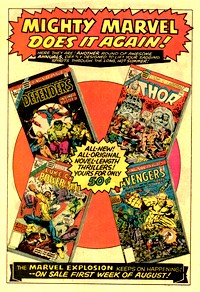

| In November 1976, the

Bullpen Bulletin was still on its way

through the alphabet as far as its title

was concerned, arriving at the letter S -

which resulted in the typically

alliterative and somewhat nonsensical

title "A Scintillating Soliloquy

of Stunning Stories, Sagacious Sagas, and

Senses-Shattering Super-Heroes!". The headline item of

Stan Lee's Soapbox column was

the kind of story that makes you wonder

(these days, not back then) how much

actual fact it contained. Were hoarders

really buying "all the copies of

a new issue as soon as it appears (...)

and sell them later at a big profit",

or were "True Believers

everywhere (...) complaining that our

mags are selling out too fast"

related more to a distribution problem?

Whatever it was, it certainly allowed

Stan Lee to throw in a plug for Marvel's

subscription offerings - which also

happened to be the subject of a full-page

in-house ad.

|

|

In-house ad from Eternals #5

|

As for the

actual Bullpen Bulletins' various

ITEM!

bullet points, they were - as usual - mostly

concerned with staffers new and old, plugs for

upcoming Treasury Editions, and a push for

another collaboration with Simon & Schuster

(albeit a slightly oddball one in the form of The

Mighty Marvel Comics Strength & Fitness Book).

|

|

| |

Marvel was selling its brand and properties left,

right, and centre, and doing comparatively well

(certainly in comparison to their main competitor, DC

Comics). Sales of comic books were up, dipping only

slightly during the second half of the year - but still

in overall positive territory compared to 1975, whereas

DC's numbers were only going one way, and that was down

(Tolworthy, 2016). But the bottom line would be that "running

a comic book company was no cake walk in 1976",

as Joe Brancatelli famously put it in one of his monthly

columns for Warren in 1977.

"Whatever improvements

were made at Marvel [in 1976] came by virtue of the

fact that they raised comic prices, made additional

non-comic sales (...), cut printing costs by lowering

the print runs and subsequently had less books

returned unsold since less were printed in the first

place. (...) The company decided to print less comics

in 1976 rather than trying to sell more."

(Brancatelli, 1977)

The fact that "our mags

are selling out too fast" may thus have been

caused more by a curbed supply rather than a surging

demand (which no doubt is what readers inferred from Stan

Lee's statement).

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

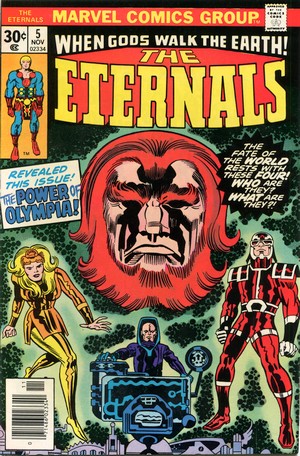

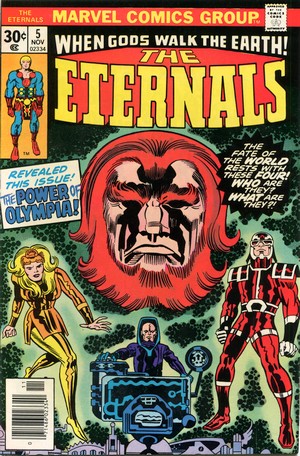

ETERNALS

#5

November 1976

(monthly)

On Sale: 10 August 1976

Editor

- Jack Kirby & Archie Goodwin

(consulting)

Cover - Jack Kirby (pencils) & Frank

Giacoia (inks)

"Olympia" (17

pages)

Story

- Jack Kirby

Pencils - Jack Kirby

Inks - Mike Royer

Lettering - Mike Royer

Colouring - Glynis Wein

STORY

OVERVIEW - Having been

informed by fellow Eternal Sersi of the

Deviant attack on New York, Makkari and

Thena, daughter of the Prime Eternal

Zuras, leave the eternal city of Olympia

to help Earth. Just as Sersi and Margo

Damian are captured and readied to be

taken to the Deviant's undersea kingdom

of Lemuria, Makkari and Thena swoop in

and take out several attackers. At the

same time, officials at the Pentagon

review the surveillance photographs taken

in the Andes Mountains of the Celestial

God-Ship.

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| In their very own way,

the Eternals were a fun read for most of the

time, and Jack Kirby's artwork gave it a very

distinctive look. In terms of storyline, however,

the title could be a real mouthful. But in order

to fully understand the Eternals, one needs to

understand the enormous amount of Jack Kirby's

personal and professional history tied into this

title. Kirby left

Marvel Comics in 1970 for DC Comics, increasingly

angered by what he perceived to be an intentional

and continuous denial of credit for his share in

creating much of the Marvel Universe. DC promised

him not only full credit but also full artistic

freedom, the result of which was Kirby's

"Fourth World" meta-series, a blend of

classic mythology and science fiction. For some

it was the ultimate comic book saga, while to

others it just all seemed too convoluted and

confusing, and the latter group of people seemed

to be in the majority as Kirby's work didn't sell

near as well as DC needed it to (Stump, 1996).

|

| |

|

| As the number of cancellations of

Fourth World titles grew, so did Kirby's

disappointment with DC, and after his contract

ended in Spring 1975 Jack Kirby once again went

to work for Marvel. In return for this industry

scoop, "the King" essentially just

wanted to be left alone to write and edit his own

stories with no co-plotters or tie-ins with other

titles done by other people, keeping his work

deliberately detached from Marvel continuity

(Gartland & Morrow, 2013). In terms of new concepts,

Kirby started working on The Eternals,

which was thematically similar to his DC work

(especially the New Gods) but actually

took its core inspiration from Swiss author Erich

von Däniken's Chariots of the Gods - in

which the author made the both fascinating and

controversial claim that Earth had been visited

by aliens in the past and that evidence of this

could be found in artefacts and the mythologies

of ancient civilizations.

Working on this premise,

Kirby postulates such an alien visit in our

prehistoric past. Through genetic

experimentations these "Celestials"

create three distinct species: Earth's humans,

the "Deviants" (whose genes are so

unstable that every one of them is grotesquely

different and they all have lived on the bottom

of the ocean for centuries), and the

"Eternals" (undying and beautiful

humanoids with superhuman mental gifts).

|

|

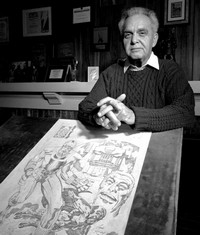

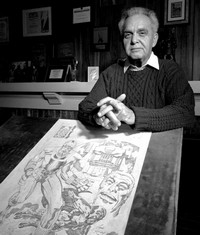

Jack

Kirby

(1917-1994)

|

|

| |

| It was another typically

high-flying Kirby concept, accompanied by artwork of

complex machinery, but at least to start with it seemed

to work well enough. By the time Eternals #5 hit

the news stands, Kirby was still somewhat building his

cast and plotting out the general theme, and the letters

page was full of praise for the first two issues. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Generally speaking (although

obviously a matter of taste), a certain

"looseness" seemed to plague Kirby's

work since his return from DC. His plotting would

sometimes go off in more directions than most

readers were willing to accept let alone care

for, and even his artwork at times showed signs

of letting up, as the arguably bland and

simplistic splashpage of Eternals #5

would seem to indicate (bearing in mind that the

splashpage of any comic book was the second most

important selling point after its cover). Ultimately, his work came

across as being too detached from what the

average reader would expect. And since Marvel

Comics had always been about finding "the

formula that sells", this became a problem,

aggravated by the fact that by that time Kirby

was living and working in California and the

Marvel offices were in New York. Communication

was slow, and it seems that opinions on Kirby's

work started to drift apart significantly - some

still admired it, while others simply couldn't

stand it (Gartland & Morrow, 2013)

|

|

| |

| Only one letter published in Eternals

#5 headed in that direction, but the call to connect the

Eternals to the rest of the Marvel Universe got louder

and louder everywhere else - not the least from editorial

staff at the House of Ideas. |

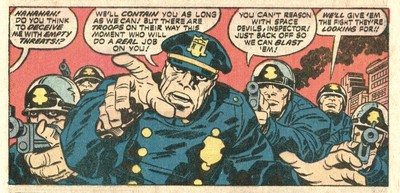

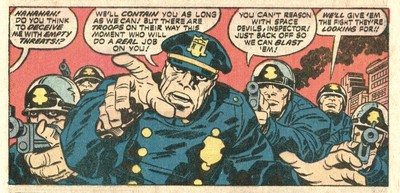

"In addition

to disliking the dialogue (which was

sometimes ludicrous but always earnest, as in

the scene [from Eternals #5] when an innocent

bystander ran through crowded metropolitan

streets yelling "Run! Run! The Devil's

come back from space with an army of

Demons!"), they wanted more renowned

Marvel heroes in the book." (Ro,

2004)

Kirby only halfheartedly

tried to appease his critics, such as explaining

the presence of the Hulk in a later issue as an

instance of an android robot. This only

frustrated his critics more, but there were also

actual problems, as Scott Edelman (who as

Assistant Editor had the task of proofreading

Kirby's material) points out.

"I was

genuinely horrified by the clunky captions

Kirby was providing and the wooden dialogue

he was putting into the mouths of his

characters. I also recognized that it had

probably always been that way, that [Stan]

Lee had been able to add a veneer of

verisimilitude over Kirby’s images which

had pulled it all together in the past, that

could have done the same in the ’70s if

the relationship between the two men

hadn’t imploded." (Edelman,

2012)

Gartland & Morrow

(2013) claim that such critical reception of

Kirby's work was partly fabricated by people

inside Marvel wanting to bully Kirby out.

|

|

|

|

| |

Howe (2012) on the other hand quotes an unnamed

Marvel staffer who wrote positive "fan letters"

to try and counter-balance all the negative feedback

pouring in - and Edelman himself is also quite clear in

refuting the claim.

"I never tried to

usurp Kirby’s role as the scripter of the books

he drew, and I never tried to get him fired (...) as

far as I know, none of the other assistant editors

attempted to unseat the King either (...) I have to

wonder whether some Kirby supporters are so certain

in their cause that they are invested in the idea

comics fandom could not possibly have grown

dissatisfied with what Kirby was doing without Marvel

staffers surreptitiously egging them on. Isn’t

it possible that fandom soured on Kirby’s prose

on its own, with no need for a whispering campaign to

urge them to do so?" (Edelman, 2012)

On the up side, Kirby still

managed to infuse his art with a certain dynamic, and if

you liked his 1950s horror title monster work, the

visuals of the "demons from space" in this

issue looked and felt like a very pleasant throwback.

|

| |

|

|

But regarding his scripts, an

increasing amount of corrections of dialogue made

in NYC (with Kirby only finding out when he saw

the printed copies) made the situation more and

more difficult. When Eternals

#5 hit the newsstands in August 1976, Kirby's

contract renewal was still a good 18 months out,

but when it finally came up for discussion in

April 1978 (three months after Eternals

would be cancelled with

issue #19), Stan Lee made it clear that he

only wanted Kirby's artwork and no more of his

scripting (Howe, 2012).

Not surprisingly, Kirby

left, went to work for the animation industry,

and never returned to Marvel again.

|

|

| |

|

|

Copies

of the Eternals

appeared frequently in MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS, and although

the evidence available at this

point in time continues to

present some holes in the data,

Marvel's MULTI-MAGS may

even have carried a complete and

full run of all 19 issues. With a

little bit of luck, readers had

certainly been able to pick up

the previous issue,

Eternals #4, and

thus continue reading the story

of the Deviants' attack on NYC. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

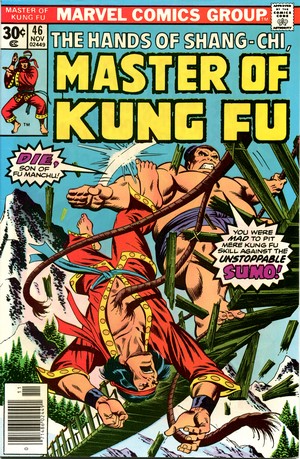

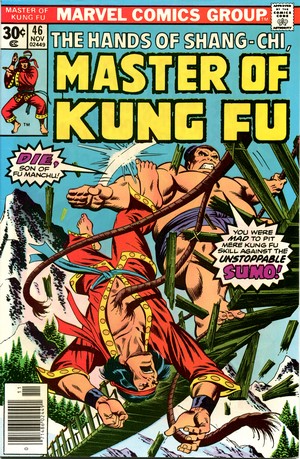

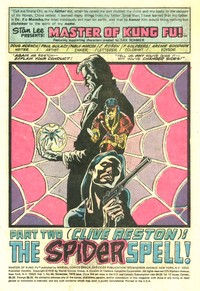

MASTER OF

KUNG FU #46

November 1976

(monthly)

On Sale: 10 August 1976

Editor - Archie

Goodwin

Cover pencils - Al Milgrom

Cover inks - Jack Abel

"The

Spider Spell!"

(17 pages)

Story - Doug Moench

Pencils - Paul Gulacy

Inks - Pablo Marcos

Lettering -

Joe Rosen

Colouring - Petra Goldberg

STORY

OVERVIEW - (Part

2 of 6; each issue is narrated by

a different character, this one

by MI6 agent Clive Reston) Reston

is captured, and Shang Chi must

get past a man-mountain of a sumo

wrestler who can resist the most

powerful Karate blows. Meanwhile,

Fu Manchu is taking further steps

for his return.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Master of Kung Fu was

one of Marvel's many titles of the 1970s which moved

somewhat outside of the traditional superhero theme. The

intention was for the House of Ideas to potentially tap

into new readership groups or expand the interests of

existing ones by opening up new genres. Star Wars is

of course the best known and also the most profitable

such venture, along with Conan the Barbarian,

but Master of Kung Fu was pretty successful too. |

| |

Marvel had started to fully

embrace the genre expansion by the very early

1970s, and the case for a Kung-Fu themed title

was brought up by Steve Englehart and Jim Starlin

after having seen the TV show Kung Fu (Pearl,

2012).

"We went to

Roy Thomas, Marvel's Editor-in-Chief, and

proposed our series. Roy was not impressed;

martial art was not his thing. But he was at

least intrigued by our enthusiasm, so he did

his [Editor-in-Chief] thing and said he'd

okay it if we incorporated Fu Manchu, a more

traditional Asian character, as a sales draw

(...) I'd read all the Fu Manchu books, and I

liked pulp. I could write Fu Manchu - if he

absolutely had to be in the book. Jim and I

didn't think he did (...) but Kung Fu was

still just a blip on the radar, and editorial

decisions are based on what's worked before,

so Fu Manchu was in." (Englehart,

2016)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Acquiring the rights to Sax Rohmer's

characters came with a short-term sales boost and

a long-term problem. The sales boost worked

instantly. Shang-Chi made his debut in Special Marvel Edition #15

(December 1973), a former reprint title,

and resonated so well with readers that

Special Marvel Edition was

simply retitled as of issue #17, becoming Master

of Kung Fu (with the prefixed tagline The

Hands of Shang-Chi and the fan-favourite

acronym MOKF). It ran for 109 issues

before being cancelled with Master of Kung Fu

#125 in June 1983.

|

|

| |

| The long term

problem was that while Shang-Chi was a Marvel

character, Fu Manchu was not. Created by Sax

Rohmer for his 1913 novel The Mystery of Dr.

Fu Manchu (released in the US as The

Insidious Dr. Fu Manchu), the character and

name had to be licensed from the Rohmer estate. A

major reason for doing so, it seems, is that Roy

Thomas at the time had been told that DC might

look into a Fu Manchu title if Marvel did

anything in the way of Kung Fu (Cronin, 2019). However, when

Marvel cancelled the series, they lost the rights

to Fu Manchu (as was the case with many

characters Marvel licensed in the 1970s, e.g. Godzilla). It

created a problem for Marvel's own Shang-Chi

(since so much of his character background

was tied up in the relationship with his evil

father), making further appearances of the

"Master of Kung Fu" somewhat

complicated and leading to various retcon

measures in attempts to not have to use the name

Fu Manchu.

In essence, Master of

Kung-Fu and the adventures of Shang-Chi were

penned in an action and espionage adventure vein

(which also put them very much in tune with

Rhomer's later original Fu Manchu books), whilst

remaining true to Englehart's vision of a

spiritual and philosophical (and thus reluctant)

warrior who never wavers in fighting his father's

evil schemes.

But what was therefore

totally impossible for the longest time, was for

Marvel to reprint any of the original Master

of Kung Fu material - until a licensing

agreement was once again reached with the Rohmer

estate in 2015. As a result, Marvel rushed the

entire Bronze Age MOKF material to the printers

and published it in four volumes of Omnibus

format collections between 2016 and 2017.

|

|

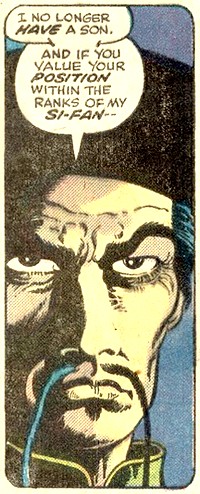

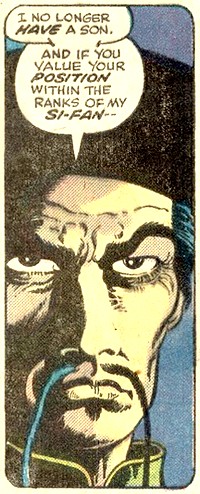

Even

though actually only appearing in very few panels

of this issue of MOKF and not actually mentioned

by name, Fu Manchu is an essential part of the

plot - a fact that prevented reprints for

decades.

|

|

| |

Steve

Englehart (*1947)

|

|

Clearly one of the Marvel comic

books of the early 1970s where writers and

artists were aiming at an audience in the teenage

and older age range whilst using literary

characters, it enjoyed a smiliar success as Tomb

of Dracula.

"A

lot of us back then were trying to break out

of comics just for kids, and it was very

possible for us to do those things on the

non-superhero books, because no one was

paying attention. So Roy Thomas could do that

on Conan, Steve [Englehart] could do that on

Doc Strange and Master of Kung-Fu, [Steve]

Gerber could do it on Man-Thing or Howard the

Duck, and I could do it on Dracula."

(Marv Wolfman

in Siuntres, 2006)

"After

just two issues, the series was such a

sensation that [Special

Marvel Edition]

officially became MASTER OF KUNG FU (...)

Shang Chi became Marvel's most popular

character for years thereafter (...)

Unfortunately, doubling my work load was

something I couldn't do with such a

philosophical book, and rather than crank it

out, I left it. This was too bad for me, but

fortunately it was taken over by Doug Moench,

who went on to work with a series of great

artists like Paul Gulacy and Gene Day to make

it one of Marvel's truly memorable

series." (Steve Englehart, AN)

|

|

| |

|

|

This is the

second issue of a six-part

storyline culminating in Master

of Kung Fu #50, with each

issue narrated by a different

character (part 2, in this issue,

by Clive Reston). However, Master

of Kung Fu was an extremely

rare find in a MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS, so

there was no way one could have

followed that arc with what was

available over the following

months in subsequent MARVEL

MULTI-MAGS

(although you could have picked

up the previous issue,

Master of Kung Fu #45,

with a bit of luck). |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

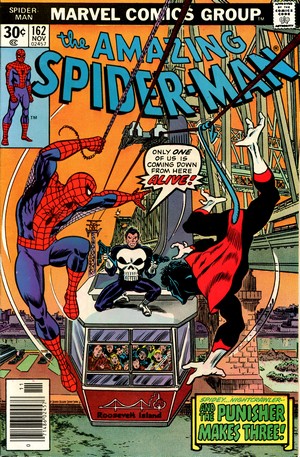

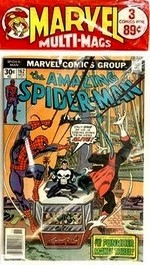

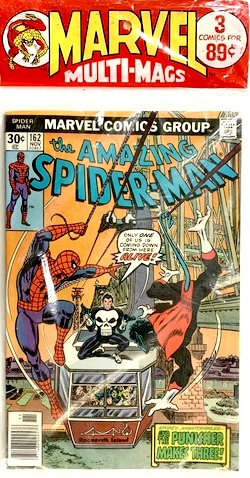

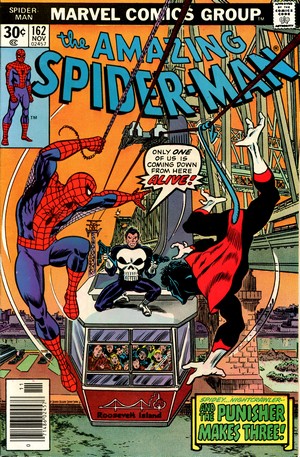

AMAZING

SPIDER-MAN

#162

November 1976

(monthly)

On Sale: 10 August 1976

Editor - Len Wein

Cover - Ross Andru (pencils)

& John Romita (inks)

"Let

the Punisher fit the Crime!"

(18 pages)

Story - Len Wein

Pencils - Ross Andru

Inks - Mike Esposito

Lettering - John Costanza

Colouring - Glynis Oliver

STORY

OVERVIEW - The

Punisher tracks down Spider-Man

and Nightcrawler, believing that

one of the heroes framed him as

the Coney Island sniper. After an

all-out brawl, the Punisher and

Spider-Man agree to team-up to

uncover the truth behind the

shootings, and they succeed in

revealing the true identity of

the gunman, who turns out to be

the villain Jigsaw, seeking

revenge for the fact that the

Punisher caused his facial

disfigurement. And J. Jonah

Jameson is seeking to have yet

another go at a Spider-Slayer.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Whereas DC's highly

structured approach to their comicpacks resulted in

zero duplicate titles across different bags, the same

could not be said for Marvel's Multi-Mags, and late 1976

was an especially chaotic period in that sense - with

numerous identical titles packaged into different

Multi-Mags of the same month. |

| |

| For the October 1976 run of

Multi-Mags there are no less than three

documented instances of duplicates packaged into

different packs: Eternals #4 (Amazing Spider-Man #161, Doctor Strange

#19, Eternals #4)

Eternals #4 (Thor #252, Eternals #4,

Captain America #202)

Daredevil #138 (Daredevil #138, Ka-Zar

#18, Marvel Spotlight #30)

Daredevil #138 (Double Feature #18,

Daredevil #138, Marvel Super-Heroes #60)

Marvel

Spotlight #30 (Daredevil #138, Ka-Zar #18, Marvel

Spotlight #30)

Marvel Spotlight #30 (Master of Kung Fu #45,

Tomb of Dracula #49, Marvel Spotlight #30)

But in

November 1976, Amazing Spider-Man #162

topped them all - being packaged into no less

than three different Marvel Multi-Mags (which is

why it is discussed in more detail here).

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

A packaging policy of this kind didn't alienate the

targeted market base much (such as parents or

grandparents buying a small treat for their kids or

grandchildren), but it didn't win any favours with the

actual comic book readers - if the problem of ending up

with duplicates for issues purchased elsewhere was

already a concern, then getting multiple copies of the

same issues in different comicpacks of the same month

really was bad news.

"I had so many

comics, the odds were I'd wind up with dupes (...)

that was why Comicpacs did not work for me."

(Evanier, 2007)

Things would not improve much in

that respect throughout 1977; the situation was even

complicated a bit by the fact that Whitman Publishing

would start putting out their own 3-packs, with

(obviously) no regard for the contents of Marvel

Multi-Mags available at the same time. It simply was just

another fact of life for comic book aficionados of the

1970s.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

In-House

ad from Eternals #5

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

| BRANCATELLI

Joe (1977) "The Comic Books",

in Creepy #92 (October 1977) BREVOORT Tom

(2007) "Marvel Multi-Mags", Blah Blah

Blog, originally published online 28 April

2007, reposted 18 April 2020

CRONIN

Brian (2019) "Did Marvel Have a License for Fu

Manchu Before Shang-Chi Was Created?", published online at CBR,

27 May 2019

EDELMAN

Scott (2012) "Revisiting Jack

Kirby’s return to Marvel Comics", Scot Edelman

Blog, published online 27 May 2012

ENGLEHART

Steven (AN) "Master of Kung Fu", Steve

Englehart Writes, published online (date

unknown)

EVANIER

Mark (2007) "It's

in the Bag!", published online in News

From Me

GARTLAND Mike

& John Morrow (2013) "You can't go home again - Kirby's

1970s return to the "snake pit" of

Marvel Comics",

in Jack Kirby Collector #29

HOWE

Sean (2012) Marvel Comics - The Untold Story,

Harper Collins

PEARL Barry

(2012) "Lost in Licensing: Exit Fu Manchu", published online at Comic

Book Collectors Club, 27 June 2012 (accessed

through archive.org)

RO

Ronin (2004) Tales to Astonish - Jack Kirby,

Stan Lee, and the American Comic Book Revolution,

Bloomsbury

SIUNTRES

John (2006) "Marv Wolfman by Night", Word

Balloon: The Comic Creator's Interview Show

(transcribed from the podcast originally

available online at wordballoon.libsyn.com)

STUMP

Greg (1996) “Infantino Raises

Questions About CBG Letters Policy Following

Kirby Controversy Flare-Up”, in The

Comics Journal #191 (November 1996)

TOLWORTHY

Chris (2016) "Marvel

and DC sales figures",

published

online at zak-site.com

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

(c) 2023

uploaded to the web

15 October 2023

|

| |

|

|

|