|

| |

|

|

|

|

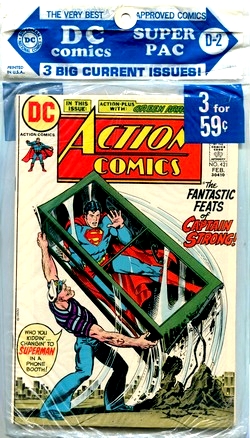

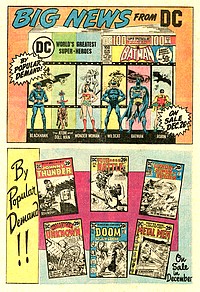

BATMAN,

SUPERBOY & SUPERMAN

BACK

TO BACK IN A

FEBRUARY

1973 DC SUPER PAC

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

DC COMICS

SUPER-PACs |

|

The early 1960s

brought both good and bad major

changes for the comic book

industry. The hugely successful

comeback of the superhero genre

created a streak of new

opportunities and creativity. At

the same time, however, small

stores which had carried comic

books for decades were pushed out

of business by larger stores and

supermarkets, and newsagents

started to view the low

cover prices and therefore tiny

profit margins comics had to

offer as a

nuisance. Many ideas on how

to turn these developments around

were put forward by different

publishers, but the most

successful concepts strived to

open up new sales opportunities

and markets and thus tap into a

new customer base. One place

these potential buyers could be

found was the growing number of

supermarkets and chain stores.

But in order to be able to sell

comic books at supermarkets, the

product would have to be

adjusted.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Handling

individual issues was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Outlets were even

supplied with dedicated Comicpac

display racks, which enhanced the product

appeal even more. It didn't matter

therefore that buying these three comic

books in a comicpack for say 59¢ (rather

than from a newsagent for 60¢ in that case) clearly presented no

real bargain - it was the opportunity and

convenience to pick up a few comics at

the same time parents and adults did

their general shopping. Neatly

packaged, it almost became an entirely

different class of commodity. DC's

"comicpacks" were, in a word, a

success - so much so that other

publishers quickly started to copy it.

"The

DC [comic packs] program lasted well

over a decade, with pretty high

distribution numbers. The Western

program was enormous - even well into

the '70s they were taking very large

numbers of DC titles for distribution

(I recall 50,000+ copies

offhand)." (Paul Levitz, in

Evanier 2007)

|

|

|

| |

| By the

early 1970s, DC relaunched their comicpacs, calling them DC

Super Pacs, and they continued to sell well

throughout the 1970s. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

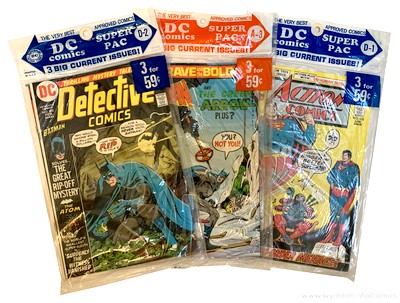

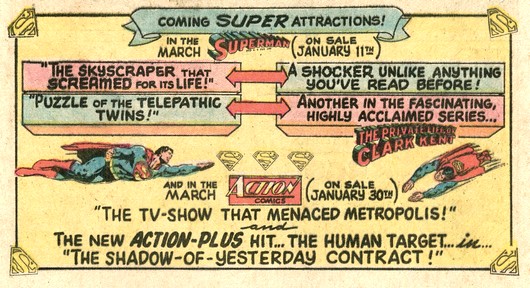

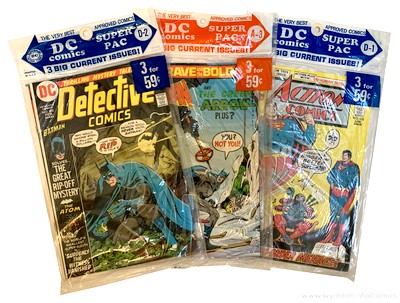

This February (D-2) 1973 DC SUPER PAC bundles together Detective

Comics #432, Superboy #193, and Action

Comics #421, making it an all-out superhero

comicpack featuring two flagship DC characters

(Superman and Batman). Right

from the start in 1961/62, when DC Comics

launched the Comicpac, all of their

multi-comic packs were reference-numbered using a

letter plus digit, e.g. B-3. And since DC wasn't

just filling plastic bags at random with any

comic books, a B-3 pack from a specific year

would carry the same titles and issues no matter

where or when it was sold (rare packaging errors

aside).

By 1964 the digit would

refer to the month and contain comic books with a

January cover date (or January/February in the

case of bi-monthly titles), and the letters (A

through D) marked the four different packs per

month (which was the rule from mid-1972 to 1978,

when DC ended their own comicpacks).

"D-2" therefore denotes the fourth

February SUPER PAC, in this case from 1973.

|

|

|

|

| |

| No

titles had truly permanent slots in the SUPER

PACS, although there was a high level of

consistency with DC's flagship characters (the

data for 1973, for example, shows

that the SUPER PACs of that year offered

buyers complete runs of Superman and Batman

as well as the Batman team-up title Brave and

the Bold). But since sales points could vary a lot with

regard to their supplies and selection of SUPER

PACs, the availability of specific titles was

never guaranteed - which in reality was the common fate of the

average comic book reader in the 1970s Bronze

Age, whether their comic books came packaged in a

plastic bag or as single issues from a display or

spinner rack. But

since DC's editorial at large (unlike their major

competitor Marvel) still very much embraced the

"single issue, done in one" storyline

during the early 1970s, missing an issue of Batman

or Superman often didn't even matter,

since every issue would start with a brand new

story anyway (there were, of course, exceptions).

Also very much unlike Marvel, DC had no regular

editorial feature across its titles at the time,

through which the publisher would communicate

with its readership (the way Marvel and Stan Lee

did with their famous Bullpen Bulletins);

the interaction with fans and readers was limited

to the letters pages, and plugs for other titles

mostly restricted to in-house ads.

|

|

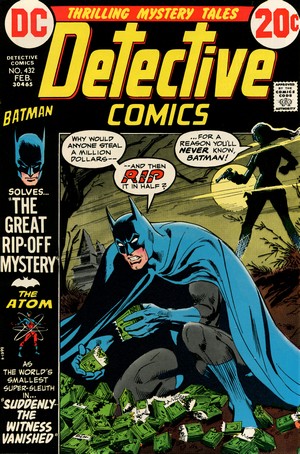

Detective

Comics #432

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

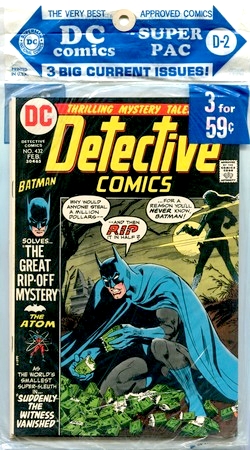

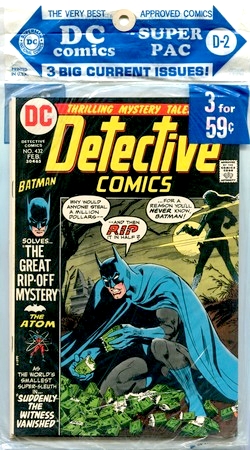

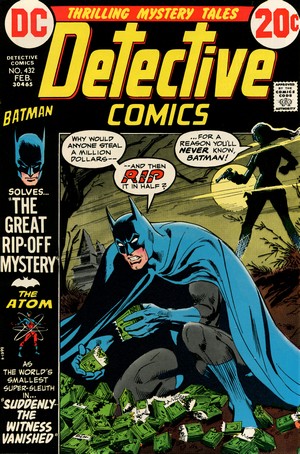

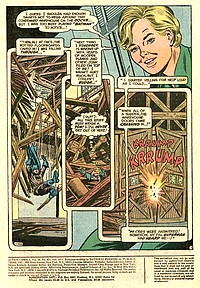

DETECTIVE

COMICS #432

February 1973

(monthly)

On Sale: 28 December 1972

Editor

- Julius Schwartz

Cover - Dick Giordano (pencils &

inks)

BATMAN: "The Great

Rip-Off Mystery!" (15 pages)

Story -

Frank Robbins

Pencils - Bob Brown

Inks - Murphy Anderson

Lettering - Ben Oda (uncredited)

ATOM: "Suddenly... the

Witness Vanished!" (8 pages)

Story -

Elliot Maggin

Pencils - Murphy Anderson

Inks - Murphy Anderson

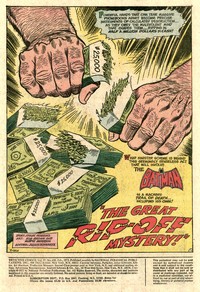

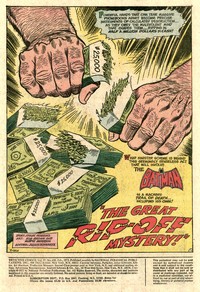

PLOT SUMMARIES - Batman

investigates the puzzling murder of a

courier carrying a briefcase full of torn

halves of paper currency. The Atom

deduces that the sudden disappearance of

a witness in court is linked to a ripple

in time and travels back a hundred years

to the past himself.

|

|

|

| |

| It had all started on November 26th 1969, when Detective

Comics #395 hit the news stands with a cover date of

January 1970. It was the first issue of DC's namesake

flagship title written by Dennis O'Neil and drawn by Neal

Adams, and the Batman was about to change in a

fundamental way as he returned to his darker and more

mysterious roots. |

| |

Other writers and artists

were already taking Batman down that path

at the time, but it was O'Neil's concept

that hit home with readers and Batman

editor Julie Schwartz alike.

"We

were going back to what Bill Finger

started with in 1939, and we added to

that what the world had learned about

telling stories since then."

(O'Neil, in Handziuk 2019)

This also resulted in

underscoring the investigative

side of the Batman character -

effectively creating the Darknight

Detective.

"When

I took over the franchise I said

okay, this is the way we do it.

Batman comics will be about superhero

stuff with a lot of action, and

Detective Comics is about the same

character functioning as a

detective." (O'Neil, in

Handziuk 2019)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

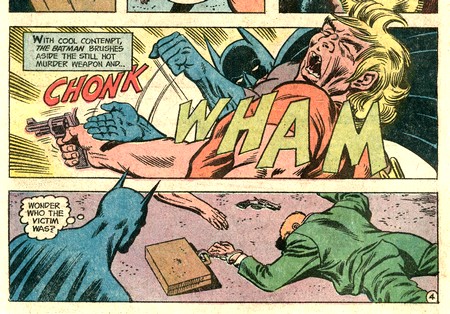

| As a result, Batman and Detective

Comics took two entirely different routes. The most

obvious change for the latter title was the complete

disappearance of costumed villains, all of which were

replaced by plain clothes thugs and evil-doers. |

| |

|

|

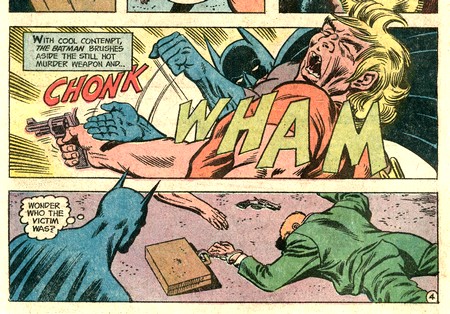

Detective

Comics #432 is an example of how

Frank Robbins handled this approach,

which often also directly involved

readers in the puzzle solving process -

matching wits and detection skills, so to

speak, with the Batman.

| |

|

|

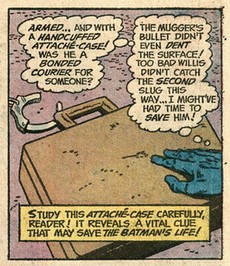

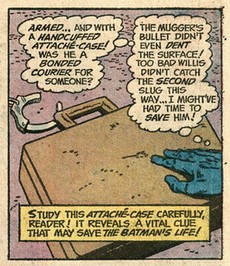

| This was done by

pointing out that something

depicted in the artwork or

mentioned in the dialogue

contained a vital clue. The

puzzle question put to the

readers was then either answered

directly on the next page or

later on in the story by showing

the Batman put the bits and

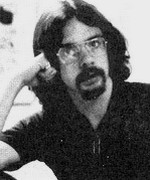

pieces together. Robbins, who

was both an artist and a writer,

started working for DC in 1968

and almost immediately took over

the scripting reigns for both Batman

and Detective Comics.

Together with Dennis O'Neil and

Neal Adams, Frank Robbins and

artist Irv Novick are credited

with returning the Batman to his

darker roots and making him a

more brooding character.

|

|

Frank Robbins

(1917-1994)

|

|

|

|

| |

| The clue to be picked up by readers here was the fact

that the attaché-case was obviously bullet-proof - and

since Batman took notice of that, he would later on be

able to use the briefcase as a shield when a mobster

pulled a gun on him. The "can

you solve the puzzle?" approach mostly made for

great reader involvement, and the letters pages at the

time were proof of the fact that it was appreciated and

savoured. It thus also made total sense to have the

tag-line "Thrilling Mystery Tales" on

the covers of Detective Comics.

|

| |

The visuals of most DC characters

were still very much streamlined at the time,

resulting in the (in)famous "DC house

style".

"DC artists

were forced to work within an established

house style that governed the page layout as

well as the look of the artwork."

(Tucker, 2017)

The Batman titles had been

slowly shaking off some of the more stringent

restrictions since 1969. New visual aspects of

the Batman had been defined, and editor Julius Schwartz now made sure

that they were adhered to.

As a

result, the actual artist chosen to draw a

specific issue had a somewhat limited impact on

what readers at the time would perceive.

|

|

|

|

| |

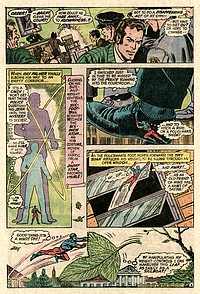

Bob Brown (1915-1977) started

his career in comic books in the 1940s, and did regular

work for DC and Marvel in the early and mid-1970s,

including almost 40 issues of Batman in Detective

Comics between 1968 and 1973, with issue #432 being

his second to last. Brown, like a number of other

veteran contributors at DC Comics in the early 1970s,

increasingly found his work to be labelled as

"old-fashioned".

"It wasn't so much

that Brown couldn't take a more modern approach to

his work as that he just plain didn't understand what

that meant. Editors kept showing him the work of new

artists, he told me. They'd say, "This is what

we want now," but Brown couldn't grasp just what

it was he was supposed to learn from the examples,

which often struck him as displaying weak anatomy,

poor perspective and other fundamental errors. It

was almost like they were telling him that "Kids

relate to crude artwork" and he knew it wasn't

that." (Evanier, 2004)

It was a tough time for Brown. His

art for Batman in Detective Comics was mostly

solid, and he did attempt to add a few dynamic features

(such as having the artwork break out of the panels).

|

| |

| The back-up feature in Detective

Comics would change frequently during that

period, but a common theme of detective work was

maintained. In this case, the Atom (billed as

"the world's smallest sleuth") solves a

case that is somewhat more "DC

superhero-ish" than other back-up features

(such as Gotham private investigator Jason Bard,

who had occupied that slot in the previous

issue of Detective Comics) - not the

least because the short (8 pages) story involved

time-travel as its major plot linchpin. Both the story by newcomer

Elliot Maggin (who had only started to write for

DC in 1972 and would go on to sign his name as

Elliott S! Maggin, the exclamation mark being a

reference to the abundant use made of it in comic

books) and the artwork by veteran Murphy Anderson

(who had started working for DC in the 1950s)

have a nice flow to them - and the splash page

featuring vignettes that form the name ATOM is

definitely a nice touch.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The Atom story also features

clues that lead up to the solution and subsequent

explanation of the strange happenings, but they are

simply presented within the story and without directly

putting them to the readers as a brain teaser - which,

given the very specialised local history knowledge needed

to connect the dots, would most likely only have served

to frustrate everybody. But, just like the better classic

crime novels from the 1930s and 1940s, the stories and

mysteries in Detective Comics were always played

fairly - the clues could indeed be spotted, so in essence

the readers always had the same knowledge as the

protagonists did. |

| |

| Jason Bard would return as

back-up feature for the next issue of Detective

Comics, and the Atom would feature next in Action

Comics #425. |

| |

|

|

|

Detective

Comics was a regular

title in DC's SUPER PACs

- six out of the twelve

issues published in 1973 were

offered in DC's

Super-Pacs. With a bit of

luck, you could therefore

continue reading the

Batman's detective

adventures (albeit in

true DC style without any

plot continuity) from the

previous issue, Detective

Comics #431. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

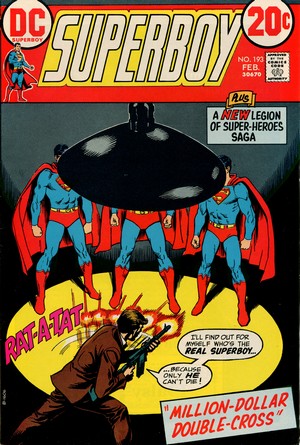

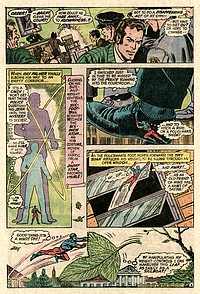

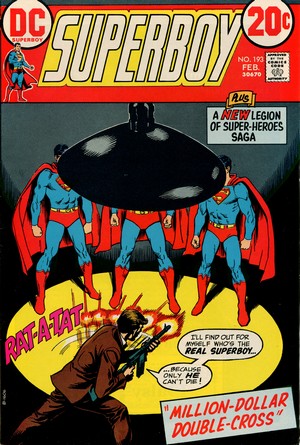

SUPERBOY #193

February

1973

(monthly,

except January, March,

July and November)

On Sale: 26 December 1972

Editor - Murray

Boltinoff

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

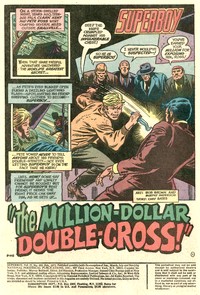

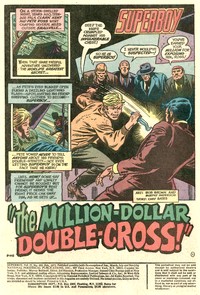

SUPERBOY:

"The Million-Dollar

Double-Cross!"

(13

pages)

Story

- Cary Bates

Pencils - Bob Brown

Inks - Murphy Anderson

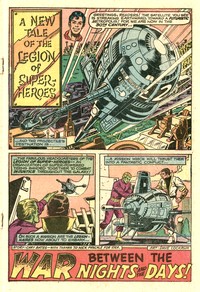

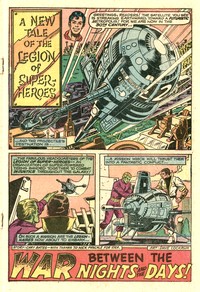

LEGION:

"War between the Nights and

Days!"

(10.5

pages)

Story

- Cary Bates, Nick Pascale

(original idea)

Pencils - Dave Cockrum

Inks - Dave Cockrum

PLOT

SUMMARIES

- Suberboy's friend Pete Ross

lures a criminal gang out of

hiding by pretending to reveal

Superboy's secret identity. The

Legion has to broker peace

between the two factions of

planet Pasnic, one of which lives

in perpetual sunlight, the other

half in perpetual darkness.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Superboy, the youthful

incarnation of Superman, was introduced in 1944 in More

Fun Comics #101 and gained his own book in 1949; Superboy

#193 belongs to this first volume of the title. From

its inception the title Superboy was applied to

Superman's adventures as a boy, teenager or young adult.

The primary setting for the stories was Smallville, but

some plots would stretch the locale to universities

attended by Clark Kent or even as far afield as

time-travel to the 30th

Century for adventures with the Legion of Super-Heroes.. |

| |

| Superboy became only the sixth DC

superhero to receive his own comic book when Superboy

#1 (March–April 1949) was published. Over the

years, the title would see the first appearances

of a number of other DC (supporting) characters,

and according to comichron.com, Superboy

often was the second-best selling superhero title

throughout the Silver Age. The character and its

various adaptations (which would also include

Superbaby) have also been credited with

popularizing the prequel (Barnett, 2020). Before

receiving his own title, Superboy was briefly

moved from More Fun Comics to Adventure

Comics as of issue #103 (April 1946), but

even after starring in Superboy as of

1949 the character continued as the main feature

of Adventure Comics throughout the

1950s, and it was in Adventure Comics #247 (April

1958) that the Legion of Super-Heroes, a group of

superpowered beings living in the 30th and 31st centuries, made its

first appearance, beginning a close connection

with the Superboy character; during the 1960s Adventure

Comics even gained the tag line "featuring

Superboy and the Legion of Super-Heroes".

The Legion moved to the

lead spot as of Adventure Comics #309

(June 1963) with 1950s Superboy reprint stories

as back-ups until making Adventure Comics

a Legion-only title as of issue #346 (July 1966).

This lasted until Adventure Comics #380

(May 1969), when the Legion was relegated to

back-up status and moved to Action Comics

for issues #377-392 (June 1969 - September 1970).

Following a short hiatus, the Legion then

began appearing occasionally as a backup in Superboy,

starting with issue #172 (March 1971).

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Superboy #193 featured a

textbox on the cover reading "Plus: A New Legion

of Super-Heroes Saga"; beginning with issue

#197, this would evolve into the subtitle "Starring

the Legion of Super-Heroes". It also, in some

ways, signalled a (slow) changing of the guard at DC

Comics; whilst the Superboy story is pencilled and inked

by veterans Bob Brown and Murphy Anderson, the Legion

back-up features artwork and inks by newcomer Dave

Cockrum (whose highly acclaimed debut on pencils was the

Legion feature in Superboy #184 in April 1972). |

| |

|

|

|

Superboy featured

in several of DC's SUPER

PACs (a total of 6 issues in 1973

alone), potentially providing

continued reading of the

adventures of Superboy over

several issues, albeit of course

without any plot continuity (and

potentially changing back-up

features, such as Superbaby in

the previous issue, Superboy

#192,

contained in the D-12 December

1972 SUPER

PAC). |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

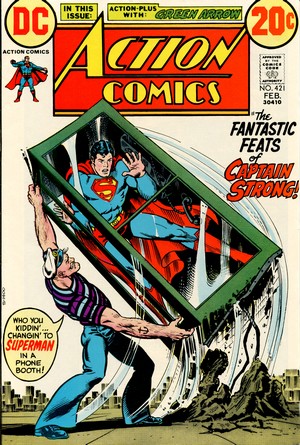

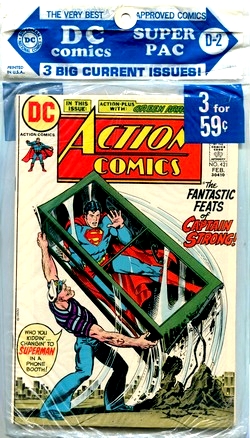

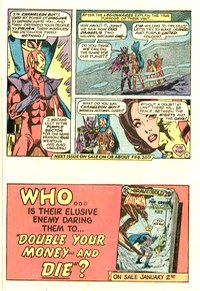

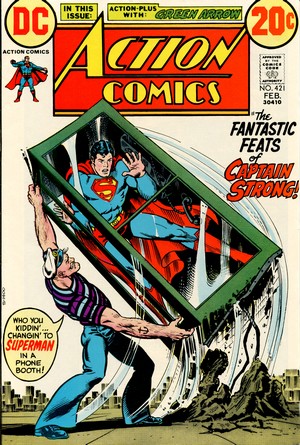

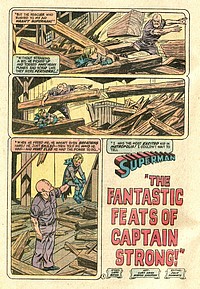

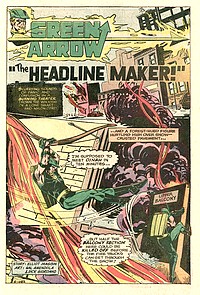

ACTION

COMICS #421

February

1973

(monthly)

On Sale: 28 December 1972

Editor - Julius

Schwartz, E. Nelson Bridwell

(assistant)

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

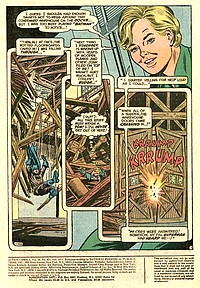

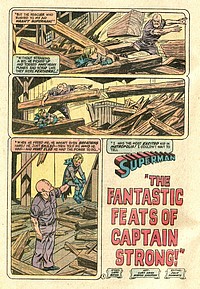

SUPERMAN:

"The

Fantastic Feats of Captain

Strong!" (15.66

pages)

Story

- Cary Bates

Pencils - Curt Swan

Inks - Murphy Anderson

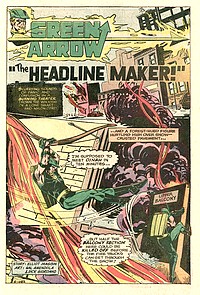

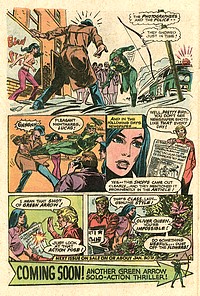

GREEN

ARROW: "The

Headline Maker!" (8

pages)

Story

- Elliot Maggin

Pencils - Sal Amendola

Inks - Dick Giordano

PLOT

SUMMARIES - An

old sailor discovers a plant from

a distant planet that gives him

temporary super powers that rival

those of Superman, whom he

idolizes, but becomes addicted to

it until Superman helps him drop

the habit. In Star City, Green

Arrow not only helps Dinah Lance

open her new flower shop but also

provides her with headline

publicity by taking down a hitman

in front of her store.

|

|

|

|

| |

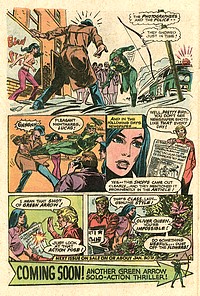

| When Action Comics #421

hit the newsstands (and the 1973 D-2 Super-Pac), the Man

of Steel's adventures were commonly in the hands of

writers Cary Bates and Elliot Maggin; in this case, Bates

wrote the Superman story and Maggin penned the Green

Arrow back-up. |

| |

Cary Bates belonged to a number

of DC Comics fans who turned writers at a very

young age in the late 1960s and early 1970s,

starting to submit ideas for comic book covers at

the age of 13 (some of which were bought and

published) and selling stories to DC when he was

just 17 years old (Eury, 2013).

"When

I sold my first script in the fall of '66 I

was a freshman in college in Ohio. My parents

started having financial problems around that

time, so had it not been for my writing I

would not have been able to continue paying

tuition… so it would not be inaccurate to

say Superman put me through college. I

graduated with an English degree, which would

have probably led me into teaching had I

stayed in the real world, but I chose to move

to New York to continue writing comics full

time." (Bates in Stroud, 2011)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

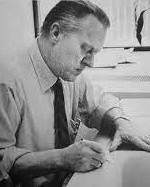

| But

whilst the scripting of Superman and other major DC

characters was entrusted to younger newcomers such as

Bates and Maggin, the artists involved belonged to the

previous generation of DC staffers who had been working

for the company for decades. This in essence teamed up

former fans with the comic book pencillers and inkers

whose work they had enjoyed as young readers, and the age

gap was always there - most visibly so when it came to

attire. |

| |

Cary

Bates

(*1948)

Curt

Swan

(1920-1996)

Murphy

Anderson

(1926-2015)

Sal

Amendola

(*1948)

|

|

Whereas

Bates and Maggin sported long hair and casual

clothes, veterans such as Curt Swan and Murphy

Anderson would always be seen wearing shirts and

dark ties. The relaxed appearance of the younger

staff was only accepted reluctantly by the

veteran DC editors, and there were certain

limits.

"Whenever

I came up to the DC offices to see [Mort

Weisinger], he insisted I wear a tie (...)

Mort once told me he didn't want Jack

Liebowitz (DC's owner back in the day) to

walk by his office to see him talking to

some"hippie". But on the plus side

at least he didn't ask me to get a

haircut." (Bates in Stroud, 2011)

Working with the same creative talent

that had left its mark on DC's 1950s and 1960s

output was also a somewhat mixed blessing.

"I

especially enjoyed my Superman and Flash

stories with Swan and Infantino, since I was

a big fan of both artists when I was reading

DC comics as a kid (...) but in retrospect

though I will say it might have been better

for my career if I had worked with a wider

range of artists, especially some of the

younger up-and-comers of the era."

(Bates in Stroud, 2011)

Long-standing

Superman artists Curt Swan (pencils) and Murphy

Anderson (inks) both produced work that not only

conformed to the DC house style but in many ways

shaped it.

"DC

artists were forced to work within an

established house style that governed the

page layout as well as the look of the

artwork. Editor Julie Schwartz's motto was

'if it's not clean, it's worthless'."

(Tucker, 2017)

By

the time the early 1970s rolled around this was

relaxed a bit, at least when it came to back-up

features. The Green Arrow feature in Action

Comics #421, however, only deviates from the

"clean" DC style in some places.

Sal Amendola was born in

Italy and started working in DC's production

department in 1969, aged 21,where he did

colouring, inking and lettering before taking

over a handful of assignments as a penciller. His art for the

Green Arrow back-up in Action Comics

#421 would, however, remain his only work for

that title.

Amendola's claim to DC

fame is the Batman story "Night of

the Stalker!" which he plotted and

pencilled; based on an idea by Neal Adams, it was

originally rejected by Batman editor Julius

Schwartz and only published several years later

after Archie Goodwin had become the Batman

editor. Finally published in Detective Comics

#439 (February 1974), it has gained the

reputation of being one of the most outstanding

Batman short stories ever.

|

|

|

|

| |

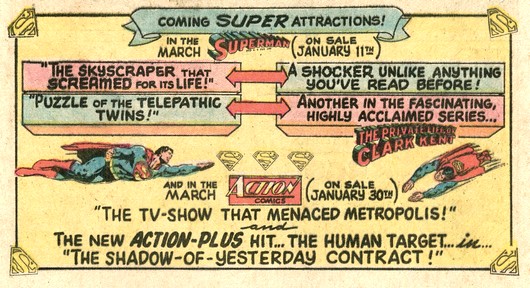

| But there was trouble brewing in

the Superman Universe. Julius Schwartz had only taken

over the editorial reigns of Action Comics two

issues previously, and he wasn't happy at all with its

main character, the Man of Steel. |

| |

"Having spent

much of the previous decade merely observing

from the cultural sidelines, the

now-thirtysomething Superman was hit hard by

the disillusionment that seized the country

in the 1970s (...) Marvel heroes bickered and

questioned and agitated - they were agents of

chaos, and they looked like the kids who read

them. Superman, on the other hand, dutifully

imposed order, and he looked like a

cop." (Weldon, 2013)

And Schwartz wasn't alone

in feeling that the character had somewhat fallen

out of sync with the times.

"O'Neil

shared his editor's ambivalence, because he

figured that such a high-profile character

would come with too many corporate strings

attached. He also found it difficult to get

excited about a character who could see

through time and blow out a star. "How

do you write stories about a guy who can

destroy a galaxy by listening hard?"

O'Neil famously joked." (Weldon,

2013)

Together, Schwartz and

O'Neil reached the conclusion that the only way

forward was to "depower" Superman -

readers needed to see him struggle.

|

|

Julius

Schwartz

(1915 - 2004)

|

|

| |

| And so, they took the man of

Steel's well-known major weakness off the board as all

Kryptonite on Earth was turned into iron by a freak

scientific experiment in Superman #233 (January

1971). At the same time, Superman's powers started to

mysteriously fade. It was a nice idea, but there simply

were too many "super-this" and

"super-that" abilities tied into Superman as a

character, and Clark Kent was still constantly having to

foil the discovery of his dual identity. |

| |

|

|

At the end of

the day, not too much changed after all - except

O'Neil didn't want to write Superman anymore

(Freiman, 2009). Possibly the most problematic

aspect, however, were the villains: mostly far

fetched, convoluted, and bland. Captain Strong is

somewhat different, but ultimately the character

and the story come across as "cute"

more than anything else, and extremely sanitized.

The very much tongue-in-cheek cover depicting

Superman trapped in the iconic telephone box /

phone booth, however, is topnotch - Nick Cardy

clearly having fun taking the mickey out of a

classic Superman cliché.

|

|

| |

| But overall, unless you were a

die-hard Superman fan, a lot of those stories didn't

really seem to go anywhere relevant. In comparison to

Marvel's output, the Superman fare also seemed to be very

much on the meek and mild side. Not surprisingly, many

readers bought Action Comics not because they

were fans of Superman, but because of the second features

appearing in the title (Kingman, 2013), but in the case

of the Green Arrow story in Action Comics #421,

this too lacks any kind of edge to it. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

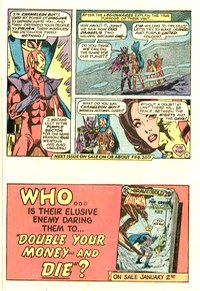

Fans of Action

Comics would not be able to

find the next issue in any DC

SUPER-PAC and would have to wait

for Action Comics #423,

packaged into the D-4 (April)

1973 three-pack. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

An overview

and analysis of all the 1973

Super Pacs is available

here. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

| BARNETT David (2020) "From

‘Endeavour’ to the resurrection of Nurse

Ratched: Why we love a prequel", The

Independent, 27 September 2020 EURY Michael

(2013) "A Super Salute to Cary Bates", Back

Issue! #62, TwoMorrows

EVANIER

Mark (2004) "On

the Passing of Bob Haney", News From

Me, published online 7 December 2004

EVANIER

Mark (2007) "More

on Comicpacs", News From Me,

published online 2 May 2007

FREIMAN Barry

M. (2009) "Exclusive

Interview with Elliot S! Maggin", supermanhomepage.com,

published online January 2009

HANDZIUK Alex

(2019) "An

Interview with Legendary Creator Denny O'Neil -

The father of Modern Day Batman", cgmagonline.com,

published online 16 March 2019

KINGMAN

Jim (2013) "The Ballad of Ollie and

Dinah", in Back Issue #64 (May

2013)

STROUD

Bryan (2011) "Cary

Bates Interview", wtv-zone.com,

published online 14 October 2011

TUCKER

Reed (2017) Slugfest: Inside the Epic

Fifty-Year Battle between Marvel and DC,

Sphere

WELDON

Glen (2013) "The

70s Were Awkward for Superman", The

Atantic, 3 April 2013

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2024-2025

uploaded to the web 18

February 2024

minor corrections 17 August 2025

|

| |

|

| |

|