SYNOPSIS

! SPOILER ALERT !

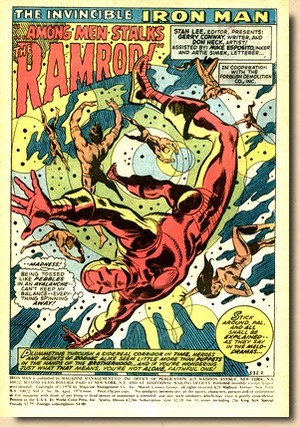

In a story arc

that started out in Iron Man

#35, branched out into Daredevil

#73, and is now being continued (and

concluded) in Iron Man #36, Iron

Man is being returned to Earth's

dimension and joins Daredevil, Madame

Masque and Nick Fury in their battle with

three Zodiac members (Capricorn,

Sagittarius, Aquarius) and Spymaster.

Once all is done

and dusted, Madame Masque - unaware of

Iron Man's secret identity - confides in

ol' Shell-Head and tells him that she

feels she should end her romantic

entanglement with Tony Stark. Keeping his

feelings to himself, Stark is terribly

upset by this, feels he needs a vacation,

and leaves the Stark Industries plant in

the care of Kevin O'Brian. However, all his

plans are interrupted by the arrival of a

gigantic android named Ramrod, sent out

to prepare for the arrival of a group it

refers to as the "Changers".

Stark suits up as Iron Man and tries to

take down the android, but overworks

himself in the heat of the battle,

resulting in too much strain on his heart

- Iron Man is down, and on the brink of

death.

REVIEW

& ANALYSIS

The Mighty

Marvel Checklist advertised Iron

Man #36 with the teaser "Tony

Stark says farewell to Iron Man! But

then, enter the sinister man-thing known

as Ramrod - and the golden Avenger must

live again - or a world dies!",

and that is pretty much what Iron Man

#36 is all about.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Essentially

your average Marvel fare, a few things about

this issue do stand out as

somewhat unusual.

Whilst continuing

storylines were a hallmark of

Marvel and an essential part in

building and advancing the

equally iconic background

continuity of the House of Ideas'

titles and characters,

multi-issue storylines would

usually start on the first page

of one issue and end on the last

or second to last page of another

issue. Iron Man

#36, however, ends a multi-issue

plot line in mid-issue and then

initiates another. In other

words: this issue contains both

the conclusion and the start of

continuing storylines.

Whilst not unique

to Iron Man #36

(an early example was the now

classic Fantastic Four

#48, which first wrapped up a

tale featuring the Inhumans and

then introduced the Silver Surfer

and Galactus), it was fairly rare

for writers to do this (and for

editors to be okay with it).

|

|

|

|

| |

| A lot more common were the title crossover stories,

and this is a typical 1970s example of how Marvel handled

these. The (utterly silly) Zodiac story started out in Iron

Man #35 and then branched out into Daredevil

#73, before heading back to Iron Man #36 for the

conclusion. There could be many

reasons for doing this. In some cases it could make sense

due to the main characters involved (such as the Dracula

crossover story with Doctor Strange in Tomb of Dracula #44 and Doctor

Strange #14 (both May 1976), but it

is fairly evident that in most cases it served as an

attempt to boost sales of one or both titles. In this

case, both Iron Man and Daredevil could do with an extra

shot in the arm.

"In those days, Daredevil

(...) sold fairly consistently, but not very well

(... ) Iron Man [was] another [such] book." (Steve Gerber in

Mithra, 1997)

Of course, back in the good old

days of the 1970s, Marvel would hope you would go out and

buy that other title, but they never truly required you

to do so. There would always be an explanatory splash

page and editorial filling you in on what had been going

on (in this case) in Daredevil #73; so even if

you jumped straight from Iron Man #35 to Iron

Man #36, you would not be too confused and still be

able to follow the overall plot.

|

| |

| Unfortunately, this

crossover had its footing in a rather

weak and confusing story involving

off-Earth action and a loose bunch of

B-list villains (three Zodiac members, of

which Sagittarius is misspelled Saggitarius

throughout). Thankfully,

it's all over by mid-issue, and as

Daredevil swings back into his own

adventures (and title), romantic problems

have Tony Stark dipping into another mood

swing that results in him brooding about

his motives for being a superhero. Is he

just hiding behind the mask? Should he

just pack up the suit for good and simply

turn to a life of fun as a playboy?

It's classic

"superhero with low

self-esteem" drama, but it doesn't

last long for Tony Stark to come to the

realization that being Iron Man is

actually the best thing he’s ever

done in his life - and that's just as

well, since another villain has just

appeared on the scene: Ramrod.

This stocky

blue-and-yellow robot mysteriously

descends from the skies, proclaiming that

his mission is to prepare for the coming

of the Changers. And he does so by

levelling multiple buildings and firing

energy blasts at anyone who dares stand

in his way.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

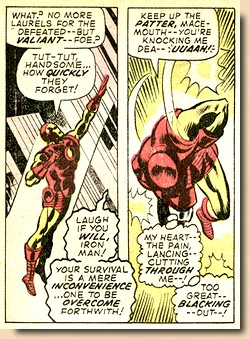

| And so, Iron Man takes on the

(incredibly verbose and boastful) robot. The battle rages

back and forth (actually it's more of an up and down),

but at one point the Golden Avenger suffers a heart

attack and crashes to the ground.

This, of course, is Iron Man's original Achille's heel:

his weak heart (whereas the superhero identity crisis

witnessed only a few pages previously was a common Stan

Lee thread with most if not all of Marvel's heroes). |

| |

|

|

And so, Ramrod

proclaims not only the fall of

his adversary, but his death - to

be continued, of course.

Unfortunately,

the storyline introducing Ramrod

doesn't really compensate for the

below par Zodiac tale, leaving

readers of Iron Man

#36 with two different plots (one

that ends and one that kicks off)

in one issue but not much to be

entertained by - although it's

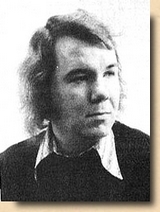

not all bad, since Gerry Conway

brings back Tony Stark's original

heart problems (seemingly taken

care of previously), adding

vulnerability and interest to

Iron Man and his alter ego.

Then again, even

Conway himself was critical of

this era of Iron Man:

"In

all honesty folks, it's a

mess [and] I'm forced to

admit, this is not out finest

hour (...) Give us all

[co-writers and artists] an

"A" for effort,

though (...) our final grade

for the course is probably,

at best, a C+. Chalk it up to

growing pains as Marvel moved

from being a small,

tight-knit group of

like-minded collaborators, to

a modern publishing

powerhouse with the ambition

(and sometimes, overreach) to

match. Like I may have

mentioned before, crazy

time." (Conway,

2011)

|

|

|

|

| |

| Back in early 1967 the almost

unthinkable had happened: Marvel had overtaken DC in

sales numbers and became the new number one of the

industry; it was now indeed the much heralded Marvel

Age of Comics. Only a year later, a change in

distributor set-up meant that Marvel was now free to

publish as many titles as it wanted, and the count went up accordingly from 14 titles in

January 1968 to 20 by July 1968. But even though Marvel

was the comic book industry's number one, DC still

published more titles until mid-1972 - when Marvel's

proliferation of titles finally turned that around too. |

| |

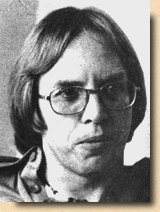

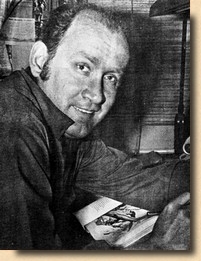

Roy

Thomas, early 1970s

|

|

"Marvel

suddenly decided to put out a whole bunch of

books (...) trying to get market share (...)

lots of stuff came out in the '70s because of

this approach." (Roy Thomas, in

Cooke 2001)

By June 1974 Marvel's

titles at the newsagents (45) outnumbered those

put out by DC (23) by leaps and bounds. But flooding the market this way

meant that the House of Ideas needed a

significant push for new creative talent.

"Marvel's

staff exploded (...) practically overnight.

Some of us knew more or less what we were

doing. Most of us, to be fair, didn't have a

clue (...) we were just making it up as we

went along." (Conway, 2011)

|

|

Gerry

Conway in 1973

|

|

| |

| For some of

the long-standing Marvel creative talents, this situation

could (and would) prove to be a challenge, and Don

Heck (1929-1995) would find himself to be one of them.

Best known for co-creating Iron Man, some of Marvel's

most classic artwork of the 1960s, and his long run on

pencilling the Avengers during the 1960s, Heck also

pencilled Iron Man #36. But in spite of being

one of the "original" Marvel artists, he found

his role at the House of Ideas had changed dramatically

by the early 1970s. |

| |

|

|

But unlike other

seasoned artists, Heck wasn't up

against newly appointed editors,

but Stan Lee himself.

"[Don

Heck] was very unhappy

because Stan would ask him to

do stuff that was more like

Kirby or Buscema and me (...)

I don't know why Stan gave

the impression that Don's

work needed to be fixed up a

little bit (...) Don was a

very good artist, but Stan

and he were constantly at

each other (...) he called

me, saying 'I don't know what

to do, I can't seem to please

Stan.'" (John

Romita Sr. in Coates, 2014)

Much later (and

on record), Lee characterized

Heck as "always a joy to

work with" and the "ultimate

professional" (Coates,

2014).

|

|

Don Heck in the

1960s

|

Things tend to mellow

down with hindsight, but back in the day,

Heck got increasingly frustrated with the

situation.

|

|

|

| |

On top of Stan Lee viewing his

pencils as "not Kirbyesque enough" (an ongoing

fixation at Marvel throughout the 1960s reported by

several artists), Heck's artwork was often spoilt by

assigning it to incompatible or lazy inkers.

"I

kept getting all the new inkers. Everyone who walked

in, I got them. A bad inker can kill artwork. I once

got some pages back from inking and I just tore them

up, that's how bad they were." (Don Heck in

Peel, 1985)

And whilst Heck was willing to

deliver artwork "no matter how tight the

deadline might have been" (Lee in Coates,

2014), even that began to backfire on him.

"He got the nickname

"Don Hack" but people forget that it was

Heck that a lot of editors went to when they needed

an entire book over a weekend. The inkers would then

have to rush through the job too. Then those same

editors would complain about the work. Well, just how

great are 22 pages going to be when you only have a

couple of days to draw them?" (Jim Amash in

Coates, 2014)

The ultimate insult, however, came

in 1980 in the form of an infamous interview in Comics

Journal #53, during which Gary Groth and Harlan

Ellison declared Don Heck to be the "worst artist in

the field". However, the two glib blabbermouths

actually confused Heck with Sal Buscema (Cronin, 2018) -

who obviously didn't deserve that kind of slander either.

|

| |

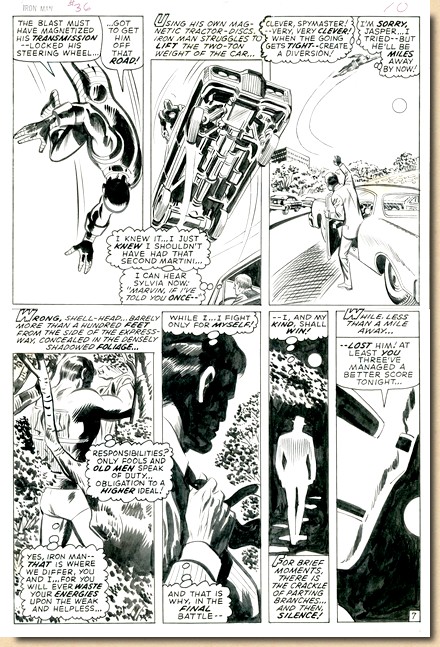

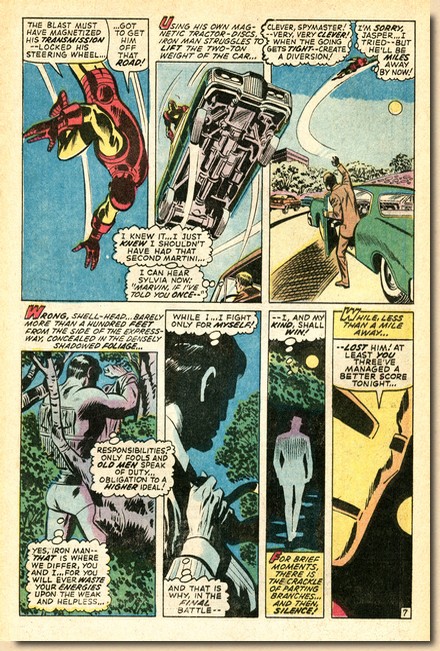

Original

artwork by Don Heck (pencils) and Mike Esposito (inks)

for page 7 of Iron Man #36 (scanned from the original)

and the same page as it appeared in print (colouring by

Sharon Cohen)

|

| |

| Heck's pencils for Iron Man #36 display a

little bit of everything; there are some beautifully

classic panels, and some lesser ones too, but they show

what his artwork could look like when inked on a good day

by an able craftsman such as Mike Esposito. As the 1970s rolled around, Heck was

handed fewer and fewer jobs at Marvel, and ultimately his

occasional assignments from rival DC Comics became his

mainstay. He left Marvel for good in 1977 and stayed with

DC until 1988 where, amongst other things, he put out

some extremely atmospheric artwork for the Jason

Bard backup feature in Detective Comics.

After that he picked up work for Marvel again, as well as

from a number of independent comic book publishers. He

died from lung cancer in 1995.

|

| |

FACTS & TRIVIA

Iron Man #36 came with the usual features - the

monthly Bullpen Bulletin (carrying another fan-favourite

alliteration headline, Wondrous words of wit and

wisdom with which to waste some time), the Mighty

Marvel Checklist (as always presenting a cornucopia of

wondrous imagination to readers with titles they might

never actually be able to lay hands on), and two pages of

letters (under the heading Sock it to Shell-Head).

|

| |

|

| |

| All of this was garnished with

colourful and exciting advertising. Definitely a Marvel forte,

it was an integral part of the house style and made comic

books from the House of Ideas ("more triumphs

from Marvel") a groovy and exciting experience. |

| |

|

|

One thing,

however, made Iron Man #36 stand

out from the rest: two

so-called half-pages. Found

fairly frequently in DC comic books at the time, the

procedure of spreading one page of artwork across

two actual pages in the finished product (in

order to spread out the space for in-house or

third party advertising), Marvel used them on

rare occasions in the early 1970s only. They were

very unpopular with the fans, and a

"revival" by DC in 2015 caused quite a

stir (Beebe, 2015).

When Marvel published Fantastic

Four #1 (November 1961), the story page

count stood at 25, but this dropped to 23 once

letter pages were introduced. By the end of 1964,

the number of story pages dropped to 20 plus 2

pages of letters (except for the anthology titles

such as Tales of Suspense which held on

to 21).

|

|

|

|

| |

| The page count then dropped in early 1970 to 19 pages

- in the case of Iron Man, this change was

ushered in with issue #24 (April 1970), whereas issue #23

(March 1970) still featured 20 pages of story. The price

remained unchanged at 15¢ The

half-pages therefore didn't actually cheat readers - they

still got the 19 pages they normally would - but it

didn't look and feel right to most readers, and Marvel

quickly reverted back to the strict separation of content

and advertising pages. Much later, in 2011, when Iron

Man #36 was reprinted in volume 7 of the Iron Man

Masterworks, the two half-pages were spliced together as

a single page.

|

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE

THOUGHT BALLOON |

|

| |

|

|

You can read more

about the "war of the

shelves" raging between

Marvel and DC in the early 1970s

here. |

|

|

|

| |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY BEEBE

Reed (2015) "Mars

comments on Twix ads controversy", nothingbutcomics.wordpress.com,

published online 8 June 2015

COATES

John (2014) Don Heck - A Work of Art, TwoMorrows

Publishing

CONWAY

Gerry (2011) "Iron in the Fire", Marvel

Masterworks Iron Man Vol. 7, Marvel

COOKE Jon B. (2001)

"Son of Stan: Roy's Years of

Horror",

in Comic Book Artist #13

CRONIN

Brian (2018) "Don

Heck Reacts to the Infamous Comics Journal Harlan Ellison

Interview", cbr.com,

published online 27 March 2018

MITHRA

Kuljit (1998) "Interview with Steve Gerber", manwithoutfear.com

PEEL

John (1985) "A signing session with Don

Heck", in Comics Feature #34, March/April

1985

|

| |

| |

The

illustrations presented here are

copyright material.

Their reproduction for the review and

research purposes of this website is

considered fair use

as set out by the Copyright Act of 1976,

17 U.S.C. par. 107.

(c) 2024

|

|

|

|