|

|

|

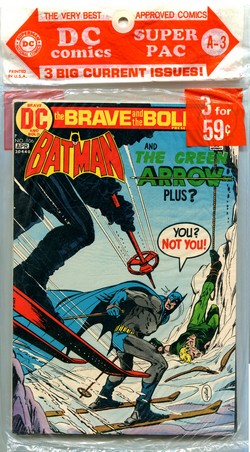

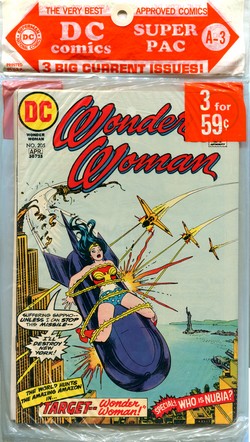

BATMAN,

PHANTOM STRANGER &

WONDER WOMAN

BACK

TO BACK IN A

MARCH

1973 DC SUPER PAC

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

| In spite of

the hugely successful comeback of the superhero genre in

the early 1960s, the comic book industry had a problem:

its traditional sales points were fading away. Small

stores that had carried comic books were pushed out of

business by larger stores and supermarkets, and

newsagents started to view the low cover prices and therefore

tiny profit margins comics

had to offer as a

nuisance. Comic book

publishers needed to open up new sales opportunities and

and tap into a new customer base. One place these

potential buyers could be found was the growing number of

supermarkets and chain stores. But in order to be able to

sell comic books at these venues, the product would have

to be adjusted. |

| |

| Handling

individual issues clearly was no option for these

outlets, but by looking at their logistics and

display characteristics, DC Comics (who came up

with the Comicpac concept in 1961) found

that the answer to breaking into this promising

new market was to simply package several comic

books together in a transparent plastic bag. This

resulted in a higher price per unit on sale,

which made the whole business of stocking them

much more worthwhile for the seller. The simple

packaging was also rather nifty because it

clearly showed the items were new and untouched,

while at the same time blending in with most

other goods sold at supermarkets which were also

conveniently packaged.

|

|

|

|

| |

Outlets were even supplied with

dedicated Comicpac racks, which enhanced the

product appeal even more since the bags containing the

comic books could be displayed on rack hooks in an

orderly and neat fashion. It almost

became an entirely different class of commodity,

and offered parents (and their kids) the opportunity and convenience to pick

up a few comics at the same time they were doing their

general shopping.

"DC's focus [for

the Comicpac] was on both the casual reader and the

parents and grandparents who were looking for

gifts." (Wells, 2012)

DC's "comicpacks" were

a success, and other publishers quickly started to copy

the concept.

|

|

|

"The

DC [comic packs] program lasted well

over a decade, with pretty high

distribution numbers. The Western

program was enormous - even well into

the '70s they were taking very large

numbers of DC titles for distribution

(I recall 50,000+ copies

offhand)." (Paul Levitz, in

Evanier 2007)

By the early

1970s, DC relaunched their comic packs,

calling them DC Super Pacs, and

they continued to sell well.

Unlike comic books

distributed to news stands and other

traditional outlets, comic packs were

non-returnable. Bags that didn't sell

were thus the retailer's problem, not the

publisher's (leading some distributors

and retailers - who most likely had

previously rigged the returnable comic

scheme, e.g. by selling comic books

without their covers - to simply split

the packs open and return the loose

comics).

|

|

|

| |

| The only way to stop such illegal

behaviour was to make comic books contained in

comic packs distinguishable from regular news

stand editions - and Western, the largest

distributor of comic packs, did just that as of

1972 by introducing their logo on the cover. DC titles distributed by

Western in their own comic packs featured the

Western "smiling face" logo instead of

the DC roundel; the covers would also not show

the issue number and the month.

DC's own comic packs,

however, continued to contain regular news stand

editions only throughout the 1970s.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

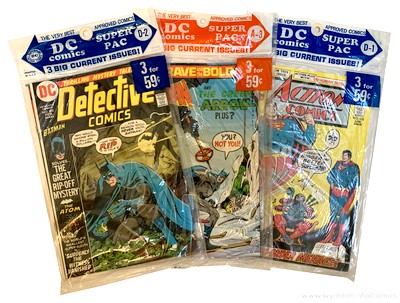

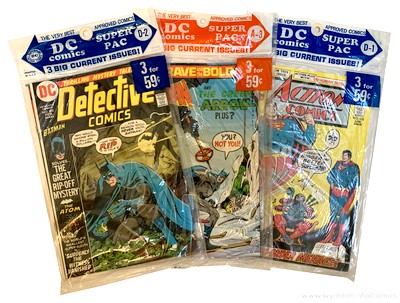

| This March (A-3) 1973 DC SUPER PAC contains three bi-monthly

titles: Brave and the Bold #106, Phantom

Stranger #24, and Wonder Woman #205. DC handled its multi-comic packs in a

very structured and organised manner; an A-3 pack from a

specific year would carry the same titles and issues no

matter where or when it was sold (rare packaging errors

aside). The digits (1-12) referred to the month and the

letters (A through D) marked the four different packs per

month. "A-3" therefore denotes the third March

SUPER PAC, in this case from 1973. |

| |

| No titles had

permanent slots in the SUPER PACS, although there was a

high level of consistency with DC's flagship characters (the

SUPER PACs of 1973 contained complete runs

of Superman and Batman as well as the

Batman team-up title Brave and the Bold). But since sales points could vary a

lot with regard to their supplies and selection of SUPER

PACs, the availability of specific titles was never

guaranteed - the common fate

of many comic book readers in the 1970s, whether their

comic books came packaged in a plastic bag or as single

issues from a display or spinner rack. In the case of DC titles this mostly

wasn't a problem anyway. Unlike their major competitor

Marvel, DC's editorial at large still very much embraced

the "single issue, done in one" storyline

principle during the early 1970s, so it often didn't even

matter in which sequence you read your copies of Batman

or Superman, since every issue would generally

start with a brand new story.

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

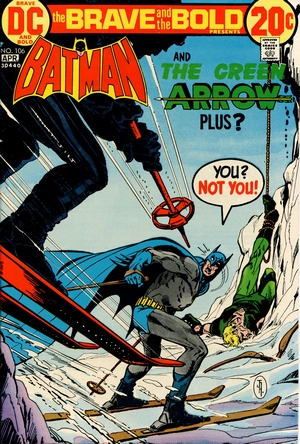

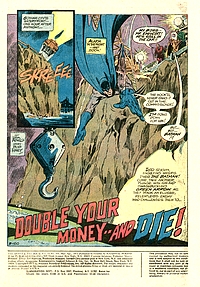

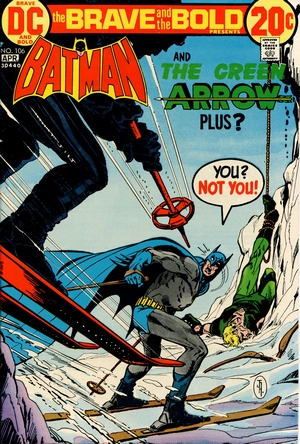

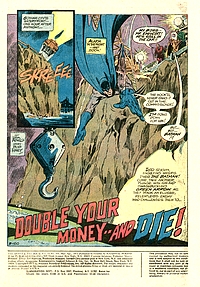

BRAVE

AND THE BOLD #106

March/April 1973

(bi-monthly)

On Sale: 2 January 1973

Editor

- Murray Boltinoff

Cover - Jim Aparo (pencils & inks)

"Double Your Money --

And Die!"

(23.3 pages)

Story - Bob

Haney

Pencils -Jim Aparo

Inks - Jim Aparo

Lettering -

Jim Aparo

Colouring - NN

PLOT SUMMARY - As the main

shareholders of the Starr Corporation are

being killed one after the other, Batman

and Green Arrow travel to Switzerland on

the trail of the mastermind behind the

killings - only to discover a familiar

Batman foe at the centre of it all:

Two-Face!

|

|

|

| |

| The Brave and the Bold

started out as a bi-monthly anthology in August 1955,

featuring characters from past ages such as Vikings,

Knights, and even Robin Hood. Following DC's successful

attempts at reviving and updating superheroes from the

Golden Age (kick-started by the Flash in Showcase

#4 in October 1956), Brave and the Bold was

changed into a try-out title as of issue #25 (August

1959), presenting a succession of (mostly successful) new

concepts which would often move on to their own title,

such as the Justice League of America in Brave and

the Bold #28 (February 1960). |

| |

| Having

previously already run a few team-up stories, Brave

and the Bold #59 (April 1965) featured

Batman for the first time. With the TV series and

the subsequent "Batmania" in full

swing, Brave and the Bold became a

dedicated Batman team-up title as of issue #74

(October 1967). It embarked on its own path of

success and became a monthly title as of Brave

and the Bold #118 (April 1975), ultimately

clocking up 200 issues until its demise in July

1983.

The title owes much of its renown and fan

interest to the fact that it was the first to

feature Neal Adams' version of the Batman, in a

team-up with Deadman in Brave and the Bold #79

(August 1968). Adams (1941-2022) went on to

provide both the covers and the interior artwork

for the next seven issues of Brave and the

Bold (followed intermittently by a few more

covers), and his style continues to define the

iconic popular culture Batman image to this day.

Whilst Adams' impact on Batman unfolded over

just a handful of issues of Brave and the

Bold, the opposite was the case for the

writer who penned those stories: Bob Haney.

|

|

|

|

| |

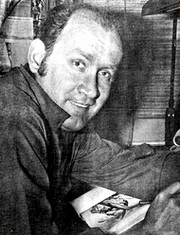

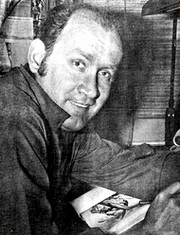

| Robert G. "Bob" Haney

(1926-2004) started working in the comic book industry in

1948 and joined DC in 1954, where over the next 30 years

he scripted just about every sort of comic book DC

published (Evanier, 2004). |

| |

Bob Haney

(1926-2004)

|

|

Sometimes called

"Zany" Haney, he was in actual fact one

of the few people at DC in the mid-1960s who

"understood

that Marvel was successfully reinventing the

super-hero comic for the current

generation" (Evanier, 2004)

Haney almost desperately

tried to bring some of that "Marvel

flavour" to the stories he was writing for

DC, and that included his very own (and sometimes

completely off-target) version of Stan Lee's

hyperbole. But Haney understood that readers

expected the writers of the comic books they were

buying to connect with them, and whilst he could

not make DC look like an exclusive secret club

the way Marvel portrayed itself, addressing

readers as "faithful ones" was

definitely a step in the right direction.

Haney's first script for Brave

and the Bold went back to issue #4 and

February 1956, and he quickly became almost a

part of the inventory of the title - so much so

that the letters page of Brave and the Bold

#146 (January 1979) informed readers that Haney

would be taking his first holiday break in ten

years and therefore miss out on scripting issue

#147.

|

|

| |

For a number of years, Haney made Brave and the

Bold (and the Batman character featured in those

team-up stories) his very own - not the least because he

had come up with the concept in the first place when the

title had experienced sagging sales.

"I soon realized that a super-hero

team-up concept was the only way to revitalize

the book. I needed a wheelhorse. Superman was

out. His editor jealously guarded that empire. So

Batman became the B&B mainstay. It worked.

Without him or with some minor or non-super

teammate, sales would tumble. So I pursued a

policy of repeated link-ups with those characters

the readers obviously favored via their sales

response." (Bob Haney in

Best of the Brave and the Bold #5, 1988)

|

| |

| Haney cared very little about the

conventionalities of the DC Universe and would sometimes

even write stories which outright contradicted them - so

much so that Haney's Brave and the Bold Batman

would be deemed to be living in an alternate reality

called "Earth-B" (Eury, 2013). |

| |

It was Haney's very

own idea of what he (along with, he assumed, a

lot of fans) wanted the Batman to be, and he

found the perfect artist for this venture in Jim

Aparo.

"I wanted the spooky dark night

Batman image of his original days. Such

artists as Neal Adams and the redoubtable Jim

Aparo brought this vision to panelled

reality." (Bob

Haney in Best of the Brave and the

Bold #5, 1988)

Jim Aparo had

started working for Charlton Comics in 1966 (as

one of very few artists who would pencil, ink,

and letter their work) before moving on to DC in

1968 (where he worked almost exclusively for the

remainder of his career).

What started

out as a fill-in job for Brave and the Bold #98

(October 1971) turned into an impressive run as

the principal artist for the title throughout the

Bronze Age - ultimately pencilling almost all of

the second one hundred issues of the title.

|

|

Jim Aparo

(1932-2005)

|

|

| |

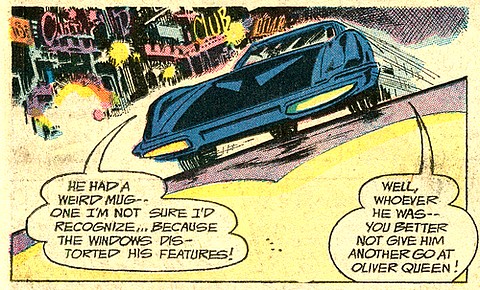

| Haney could whip up tightly

plotted scripts (e.g. his classic Brave and the Bold

stories illustrated by Neal Adams) just as easily as he

could throw out extremely loose ones with lots of logical

holes and very little overall sense. Brave and the

Bold #106 is situated somehwere in between these two

benchmarks - it's fast paced and serves up an exciting

Batman story as long as you just go with the flow and

don't ask too many questions. |

| |

|

|

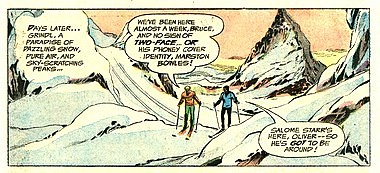

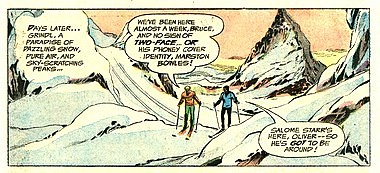

From time to time

Haney would also shift events away from

Gotham, and in the case of Brave and

the Bold #106, he sends Batman and

Green Arrow to Grindl (most likely

derived from Grindelwald), Switzerland.

The small Alpine country featured fairly

often in Batman stories of the 1970s and

1980s, either due to its secluded valleys

or its secretive bank

accounts. Bob Haney himself would

send Batman to Switzerland again,

together with the Atom, in Brave and

the Bold #152 (July 1979). And last

but not least, this choice of location

gave Jim Aparo the chance to draw

Matterhorn-lookalike mountains. |

|

|

| |

| Whilst Bob Haney certainly had a

vivid imagination, it was Jim Aparo's artwork that

ultimately brought it all to life, and his highly dynamic

style epitomized everything that would become the classic

1970s Batman look and feel. |

| |

| Aparo was a

master at perspective, and although usually

employing fairly conventional panel set-ups his

constant switching of the reader's viewpoint,

combined with his keen sense for storytelling,

made his art feel very cinematographic. Sometimes

his panels jumped right out at you, sometimes

they just drew you in. It was, quite simply,

Batman at his best. Aparo's work was so

consistently solid because he would very often

both pencil and ink his work, giving him full

creative control. And whilst taking some

inspiration from Neal Adams' redesigned Batman,

Jim Aparo developed his own typical visuals, such

as longer pointed ears on the cowl, a seamless

transition between the mask and the cloak, a

smaller oval bat insignia, and a pointedly square

chin.

|

|

|

|

| |

Jim Aparo admired Neal Adams, but it worked both

ways.

"[Adams] was

influencing everyone. He was a big influence on me.

And as good as he was, he'd been waiting at Dick

[Giordano]'s office to wait and see what I was

bringing in. Neal claimed he was a big fan of mine.

Can you believe that? He was quite a guy!"

(Aparo in Amash, 2000)

|

|

|

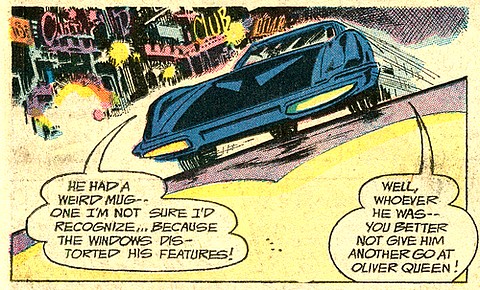

The story

told in Brave and the Bold #106

concludes on a half-page, which also

contains a highly squeezed down letters

column (more of a recap of letters

received than actual printed missives

from readers). This is mainly due to the

fact that one third of the page is taken

up by the "Statement of ownership,

management and circulation". The postal services

had required a published statement of

ownership since the 19th

Century from all publications that were

shipped Second Class, but as of 1960

publishers were also required to list

their average circulation for the year.

It is a fair guess

to assume that most readers of Brave

and the Bold #106 at the time gave

these numbers only a cursory glance (if

at all), wishing the space had been used

for more "comic book content".

Today, however, those statements of

ownership and circulation in comic books

are quite fortuitous, allowing us an easy

glimpse into print runs and sales of

earlier eras.

As far as Brave

and the Bold was concerned, the

numbers nearest to the filing date were

on the up compared with the average of

the preceding 12 months: 397,000 copies

printed (compared to the average

351,000), of which 208,456 copies in paid

circulation (179,609).

|

|

|

| |

| As was typical for the early

1970s, the attrition rate in terms of distributed but

unsold copies was terrible: totals of 186,550 (nearest to

the filing date) or 170,212 (average of the preceding 12

months) meant that a whopping 45+ percent of the print

run never made DC any money. And it was the same for all

comic book publishers across the board. The problem

really stemmed from the traditional distribution model

with returnability. The fact that the loss incurred by

unsold copies was on the publishers, not the distributors

or sales points, was a breeding ground for an attitude of

"we couldn't care less" when it came to

actually selling the product.

"A few retailers actually liked carrying

comics, but most were indifferent (...) So, let’s

say [the local distributor] actually delivered 5,000

copies [of 10,000 received at the warehouse] to the

retailers - if they bothered to deal with unwrapping

and sorting, if they had room on the trucks… Most

likely, they’d only actually deliver comics to

retailers who would complain if they didn’t get

comics and places that sold enough comics to make the

driver’s effort worthwhile." (Shooter,

2011)

Another huge problem were the

fraudulent practices it attracted.

"We [at Marvel]

actually found a company that was sending back more

copies than we shipped them. We found out there was a

printer in Upstate New York that was printing copies

of our covers to sell back to us (...) At the time we

had something like a 70 percent return rate"

(Galton in Foerster, 2010)

It all became completely untenable

by the time the 1970s rolled around, and it became the

impetus for the creation of "comic packs" such

as DC's Super Pacs and the direct market.

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

|

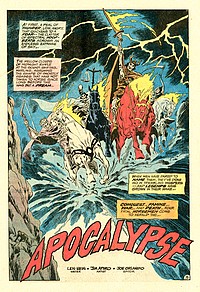

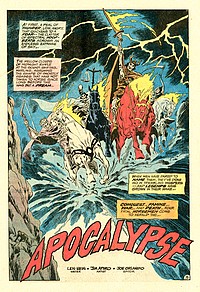

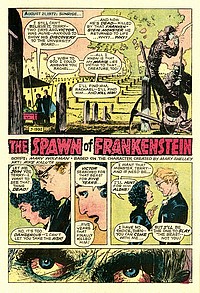

PHANTOM

STRANGER #24

March/April

1973

(bi-monthly)

On Sale: 4 January 1973

Editor - Joe

Orlando

Cover - Jim Aparo (pencils &

inks)

PHANTOM

STRANGER: "Apocalypse"

(17

pages)

Story

- Len Wein

Pencils & Inks - Jim Aparo

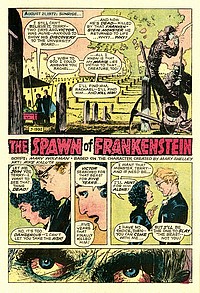

FRANKENSTEIN

: [No Title]

(5.5

pages)

Story

- Marv Wolfman

Pencils & Inks - Mike Kaluta

PLOT

SUMMARIES

- The Phantom Stranger,

Cassandra, and Tannarak travel to

Rio De Janeiro to track down the

Dark Circle and stop them from

summoning the Four Horsemen of

the Apocalypse to bring about the

end of the world.

Dr. Thirteen vows to track down

and destroy the Spawn of

Frankenstein, whilst the Monster

is out body-snatching.

|

|

|

|

| |

| The Phantom

Stranger, created by John Broome and Carmine Infantino in

1952, is one of only a handful of comic book characters

which truly elude a clear-cut characterization: Having

originated from unspecified paranormal

circumstances, he battles mysterious and occult forces,

but his identity and motives ultimately remain unknown

and unclear. |

| |

| This air of vagueness surrounding

the Phantom Stranger is sometimes mirrored in his

stories, which back in the 1970s (in which was

actually volume 2 of the series) could take on

all kinds of differing tones and directions. After

the title was relaunched for a second volume in

May 1969, Jim Aparo took over from Neal Adams and

Mike Sekowski as interior penciller with issue #7

(May 1970) and continued to provide the artwork

for the stories until issue #27 (October 1973).

Another identifying

trait of the Phantom Stranger is his role of

narrator and host, a concept which framed all the

stories of the second volume. It was a plot

device taken straight from old time radio shows

of detection, mystery and horror, where listeners

would be both warned and invited to witness what

was about to unfold.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

Phantom

Stranger #35, Gerry Talaoc

|

|

And just as had been

the case with those

old radio shows, the fact that the

Phantom Stranger was host and narrator as

well as involved character didn't always

guarantee a very active role in the

actual storyline.

"The Phantom Stranger

never really got noticed by most of

the audience because it was a mystery

book, not really a character book.

The Phantom Stranger was rarely the

focal point of the story. He was the

host, he was the interlocutor, the

interjector, he just showed up at the

right moment, and ran away." (Len

Wein in Slifer 1979)

This was also a

constant point raised in letters sent in

by readers. Some did not like the artwork

once Jim Aparo stopped doing the

interiors, whilst others did not approve

of some recurring characters which

writers had started to introduce later on

in the run. But they all seemed to agree

that they wanted the Phantom Stranger to

play a more active role in the stories.

The strength of

the Phantom Stranger lies mostly with the

character concept and the visuals. And

once again, Jim Aparo - taking over the

relay baton from Neal Adams with Phantom Stranger

#7 in early 1970 - made the

character his unmistakable own through

his mysteriously atmospheric pencils and

inks. Adams continued to provide the

covers until Aparo took over that task as

well as of Phantom

Stranger #20 (July 1972), and in a

similar fashion continued to provide

cover artwork once he left the title's

interior pencils and inks after issue #26

(August 1973).

His successor, Gerry

Talaoc, was a vanguard of Filipino

comics artists recruited in the early

1970s, and although providing solidly

attractive artwork was not held in the

same high esteem as Aparo by the readers.

|

|

|

| |

| The Phantom Stranger had

initially reprinted 1950s Dr Thirteen material from Star

Spangled Comics as a back-up feature and then went

into ever-changing set-ups with only original Phantom

Stranger material, re-introducing Doctor Thirteen as

secondary feature with original material pencilled and

inked by Jim Aparo, and reprints. |

| |

| As of Phantom

Stranger #12 Doctor Thirteen again became a

regular (original material) second feature, with

occasional reprints from titles such as House

of Secrets or House of Mystery

thrown in for single issues. Starting out in Phantom

Stranger #23 (January 1973), (Spawn of)

Frankenstein replaced Doctor Thirteen. Based on a

concept by Len Wein, scripted by Marv Wolfman,

and illustrated by Mark Kaluta, this was

essentially DC's version of Mary Shelley's

creature, revived in the US by a certain Victor

Adam. The Monster (the "Spawn of

Frankenstein" in DC's labels) kills Adam but

also accidentally causes Dr Thirteen's wife to

fall into coma - and the connections to the DC

Universe are forged. But in the end, DC's

Frankenstein Monster turned out to be even less

successful than Marvel's

version (which at least clocked up 18 issues

between May 1973 and September 1975).

Spawn of Frankenstein was the back-up feature

for eight issues until being replaced by Black

Orchid as of Phantom Stranger #30 (June

1974).

Phantom Stranger, always a bi-monthly

title, was cancelled with issue #41 (February

1976).

|

|

|

|

| |

As editor Joe Orlando put it in

his cancellation annoucnement on the letters page:

"As longtime readers know, P[hantom]

S[tranger] has always been a marginal title,

prospering at times, but usually just hanging on.

It's been nearly cancelled more times than we can

remember, and as of this issue it will finally vanish

for ever. It's a pity, and none of you feel it

anymore than we do, but we have no choice... sales do

not warrant the continuation of this mag."

|

|

|

|

In

keeping with its fringe status,

current data available only lists

two issues (#24 and #33) of Phantom

Stranger carried in a

SUPER-PAC. |

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

|

|

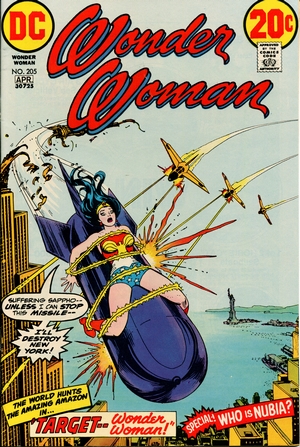

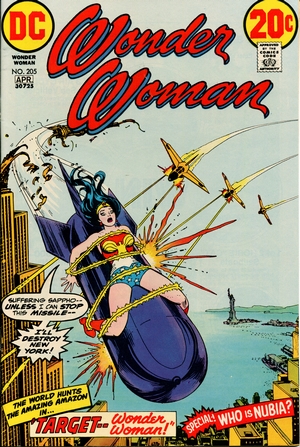

WONDER WOMAN

#205

March/April

1973

(bi-monthly)

On Sale: 4 January 1973

Editor -

Robert Kanigher

Cover - Nick Cardy (pencils &

inks)

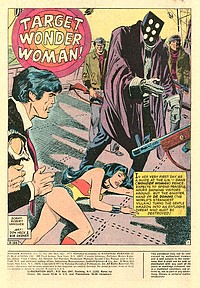

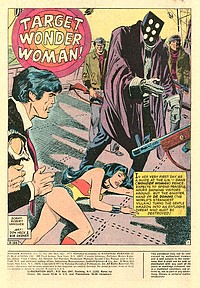

WONDER

WOMAN: "Target Wonder

Woman!" (16 pages)

Story - Robert Kanigher

Pencils - Don Heck

Inks - Bob Oksner

WONDER

WOMAN: "The Mystery of

Nubia!" (7 pages)

Story - Robert Kanigher

Pencils - Don Heck

Inks - Vince Colletta

PLOT

SUMMARIES - A

terrorist named Dr. Domino tries

to extort information on a deadly

weapon by tying Wonder Woman to a

missile and launching it.

On the Amazon's Floating Island,

the mysterious Princess Nubia

stops a fight between two rivals

for her hand by offering to fight

one of them herself.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Wonder Woman

is considered to be one of DC's "big

three" (along with Superman and Batman),

dates back to 1941, and was one of the first

female superheroes. She is also rather unique in

having been created not by a comic book writer

but by a psychologist - and that's also where the

problems start. American psychologist and

writer William Moulton Marston was an early

supporter of equality between men and women

(hence the creation of Wonder Woman).

Unfortunately, Marston was also a bondage

enthusiast in his private life, and rather than

keeping this predilection to the world of

consenting adults, he brought it to comics and

constantly had Wonder Woman, along with all the

other Amazons, tied up. And as for the imperative

flaw that every superhero required, Marston

stipulated "Aphrodite's Law" which made

Wonder Woman lose her Amazonian super strength

when her "bracelets of submission" were

chained together by a man.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Once Marston was no longer

involved in the creative process behind Wonder Woman,

it was all toned down very quickly - which also meant

that both the heroine and her title were on a zig-zag

path with very little clear direction. |

| |

Don

Heck

|

|

Back in the 1960s, Don

Heck had co-created Marvel's Iron Man and

drawn the Avengers and X-Men, but growing

increasingly unhappy with a dwindling

workload at the House of Ideas by the

early 1970s, he started doing work for DC

- at the suggestion of Jack Kirby.

"Carmine

[Infantino] was speaking with Jack

[Kirby] and mentioned he was having

difficulty finding the right artist

for the Batgirl series. Jack told him

'Why not Don Heck? He draws the

prettiest girls in comics.'" (Mark

Evanier in Coates, 2014)

Heck was

immediately put to work on various titles

featuring female protagonists, including Wonder

Woman. The problem with that title

was that it was a perennial low-selling

book.

"I

heard from someone at DC that the

daughter of the creator of Wonder

Woman has this sort of sweetheart

deal where (...) to fulfill the

lifetime contract they have with her,

they have to publish Wonder Woman, no

matter what." (Will Murray

in Coates, 2014)

|

|

|

| |

Heck recalls an

experience very much in line with such a

potential premise; at first being enthusiastic to

draw one of DC Comics' iconic characters, he

found that in his first meeting with the series'

writer

"He

looked at me like we had just won the booby

prize." (Heck in Coates, 2014).

Heck also drew the back-up feature "The

Mystery of Nubia" for Wonder Woman

#205.

This issue contains the compulsory annual

statement of ownership and circulation, but

whereas the total number of printed copies

nearest to the filing date is similar (362,000)

to those of Brave and the Bold

(397,000), the average of the preceding 12 months

(281,000) is decidedly lower (351,000). But worst

of all, the attrition rate of unpaid copies is

above 50%.

Incidentally, the well-known TV show Wonder

Woman, starring Lynda Carter, was also just

as much a middle of the road thing. Inspite of

its fanbase, the show only had decent ratings

when it aired from November 1975 to September

1979 (Hanley, 2014).

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

| FURTHER

READING ON THE THOUGHT

BALLOON |

| |

| |

|

|

"Comic

packs" not only sold well

for more than two decades, they

also offer some interesting

insight into the comic book

industry's history from the 1960s

through to the 1990s. There's

more on their general history here. |

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

BIBLIOGRAPHY

| |

| |

| AMASH

Jim (2000) "The Aparo Approach", Comic Book

Artist #9, TwoMorrows Publishing COATES

John (2014) Don Heck - A Work of Art,

TwoMorrows Publishing

EURY

Michael (2013) "The Batman of Earth-B",

Back Issue #66, TwoMorrows Publishing

EVANIER

Mark (2004) "On the Passing of Bob

Haney",

News from Me, 7 December 2004

EVANIER

Mark (2007) "More on Comicpacs", News From Me,

2 May 2007

FOERSTER Jonathan

(2010) "Marvel Comics' miracle

man set up business' success", Naples Daily

News, 30 May 2010

HANLEY,

Tim (2014). Wonder Woman Unbound: The Curious

History of the World's Most Famous Heroine,

Chicago Review Press

SHOOTER Jim (2011)

"Comic Book Distribution", jimshooter.com,

15 November 2011

LIFER Roger

(1979) "Lein Wein Interview", The Comics

Journal #48

WELLS

John (2012) American Comic Book Chronicles:

The 1960s (1960-1964), TwoMorrows Publishing

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

(c) 2024

uploaded to the web

14 June 2024

|

| |

|

| |

|