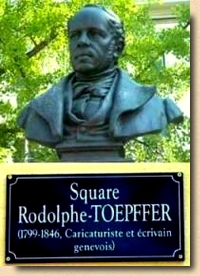

| Consider, for instance, Roy

Thomas. Well known to comic book aficionados as fan,

writer and editor par excellence who worked for

both Marvel and DC, he is also recorded as having

remarked that "I love comics, but I always

considered them, even now, a lower form of

literature". It

may be that what Toepffer and Thomas - and many others

too - are trying to say is that comics, quintessentially,

have a fairly down to earth attitude with regard to their

own posture and what they aim to achieve. And perhaps the

ambivalence surrounding comics can also be an indication

of the fact that there are many different ways of looking

at comics.

|

| I

discovered this somewhat by chance myself when I

picked up a copy of Ronin Ro's 2005 book Tales

to Astonish - Jack Kirby, Stan Lee, and

the American Comic Book Revolution in early

2007. At first glance it seemed very odd to me

that a book dealing with comics contained not a

single illustration, but the price was reduced to

such an extent that I bought it. As it turned

out, the book was fascinating to read and hard to

put down. In its pages I found all kinds of

stories around and behind the comics I had read

thirty years ago, and after re-reading some of

those 1970s and 1960s Marvel comics (readily

available in the Marvel Masterworks

series) I discovered that those comics did indeed

hold points of interest which simply weren't

accessible to a twelve-year old kid in the

mid-1970s. Of course, it's still not

Shakespeare (although it is quite possible that

Shakespeare, had he had the chance, might well

have enjoyed comic books). But, with an

academically trained way of thinking, I came to

the conclusion that there's no good reason to say

that a similarly serious approach used to reflect

on Shakespeare could not be applied to the

subject of comic books - and so I gradually

recharted my own map of comics. The pages on this

website are, in many ways, just a side effect of

this.

|

|

|

|

| Now I hasten to add that by

"academic" I refer to the methodology more than

anything else. To me at least it would seem slightly

foolish to approach a subject that doesn't take itself

too seriously in an over-serious way. Basically, it's

about what Stan Lee once said: Just because

something's for fun doesn't mean we have to blanket our

brains while reading it. For example, there are quite a few

interesting publications dealing with comics - both books

and online articles - that leave the reader guessing

about whether an author is making an original statement

or relaying information from someone else, and if so,

where this quoted information comes from. The book which

got me started, Tales to Astonish, struck

me as being especially bad in this respect. Regardless of

whether something is attributed to Jack Kirby or

supposedly quoting Stan Lee, there is no indication as to

where the author got this information from.

Okay, why should this matter.

Well, it's a question of how you approach things. Take

this page, for example. If you've gotten as far as this

paragraph (for which I applaud you), you have already

been forced to accept fairly large chunks of information

as fact, just like that. Did Goethe really praise the

first modern form of comics, or was I just making things

up because it sounds like a good story and fits my line

of thought so well? And if Goethe did indeed say

something about Toepffer's work, how can you be sure my

German is up to understanding it correctly? And did Roy

Thomas really say that about comics? When and

where? Could it be that the quote is taken out of

context? After all, someone could take this page and

quote me as saying that comics are "just a shallow

form of entertainment for readers with little or no

intellect and sociability at all". Did I say that?

Yes, I did, but if you check back on the third paragraph

of this page, you will see that I phrased it as a

question, not as my own point of view. But how could you

know if you can't go back to the source where a given

information is said to come from? This is where I find

that a consciously more precise (scholarly if you will)

approach is more than appropriate. Books on comics, their

creators, and publishers, have improved greatly in this

department over the past 15+ years, but websites have, in

general, still quite a bit of room for improvement.

|

|

|

And

this is why, on most pages on this site,

you will find source indications, notes,

and bibliographies stating clearly where

an information used in the text is taken

from. The rest is, of course, just my

personal opinion and interpretation, and

should be taken just as that - although,

with all due modesty, it is at least an

informed one.

Goethe's enthusiastic reaction

is recorded by Joh. Peter Eckermann in

his Gespräche mit Goethe

[Conversations with Goethe] in an

entry dated 4 January 1831 as well as in a

letter from Frederic Soret to Toepffer in

Rodolphe Toepffer, Correspondance

complete vol. II (413-414/Letter

355), published by Droz in Geneva (2004).

The remark by Roy Thomas comes from an

interview by Jon Cooke in Comic Book

Artist issue 13,

Son of Stan:

Roy's Years of Horror. And the Stan

Lee quote comes from his Soapbox column,

featured in the March 1970

Bullpen Bulletin.

|

|

|

Maybe by reading this far you have asked

yourself why I make no mention of the growing interest in

comic books which academia has displayed over the past

two decades, offering degrees in - broadly speaking -

comic book studies. Well, with an academic background in

an entirely different field, I am more than happy to

simply try to be a fan who looks at his subject of

interest in an informed and open way, trying to combine

the fun with some insight.

In

any case, thanks for looking.

|