|

| |

|

| |

|

|

Pecan

Street is

very much the result of "trial and

error": every now and then, something went

slightly wrong or didn't work at all - or I

simply changed my mind and approached things

differently. It's what I call "accidental

modelling". Here's an account of how it all came

together in the end, step by step (which

is why there is also a certain amount of back and

forth).

|

|

| |

Any commercial products mentioned

here are purely bona fide indications of what I have been

using myself.

I have no connection to any manufacturing companies nor

do I profit from listing any products or brands.

|

| |

|

| |

|

FIRST STEP:

PROOF OF CONCEPT

|

|

|

| |

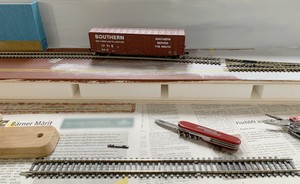

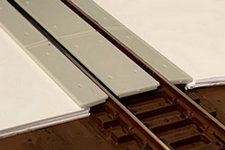

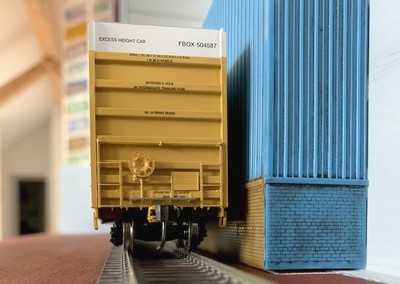

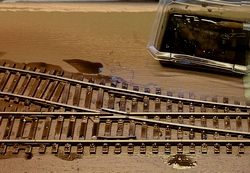

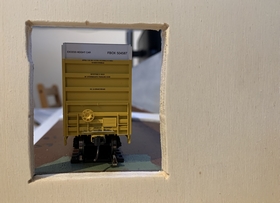

| The prime question that needed to

be answered was what two tracks within a depth of

only 6 inches actually looked like in the real

world - something that no track planning software

is truly going to be able to show. A piece of

paper cut to the required width served as a

simple set-up for this "proof of

concept". It was always clear that it was

going to be tight, but the one thing I didn't

want was for it to feel overly cramped (which is

why a boxcar was set up on one of the tracks).

|

|

|

|

| |

| This is one of those "instant moments":

either it clicks, or it doesn't. In this case, I was

happy to move on and actually start building the layout. |

| |

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

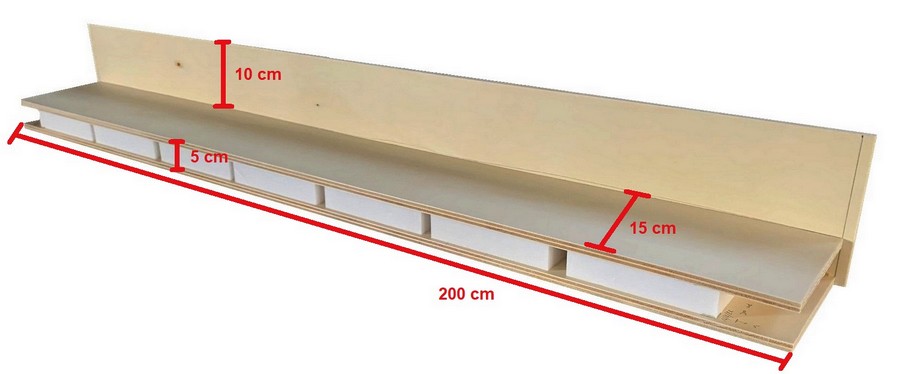

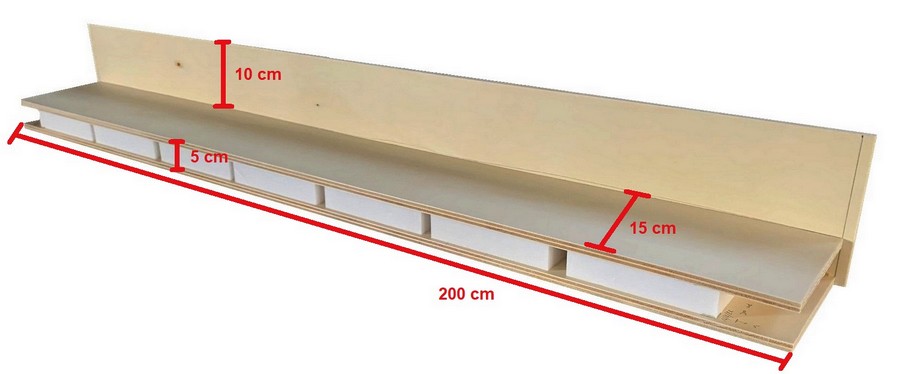

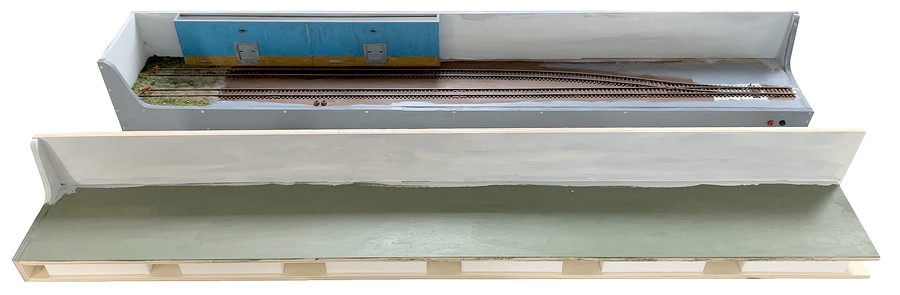

For the two

baseboard segments I returned to the construction

method used on Little Bazeley Mk2 which provided a solid yet

lightweight layout framework. Using a sheet of

10mm poplar plywood as the base, pieces of 20mm

styrofoam insulation are glued to that board,

which in turn is covered by another sheet of 10mm

ply in "sandwich style". Once

the side- and backdrop are added, this results in

a very sturdy yet lightweight layout frame and

basebaord (which also results in comparatively

silent running of trains).

There

is, however, one obvious problem with this

approach - there is no real cavity underneath the

trackbed-baseboard. In order to be able to run

cables underneath the baseboard top, the

styrofoam blocks are set back slightly, providing

some space at the front.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| |

|

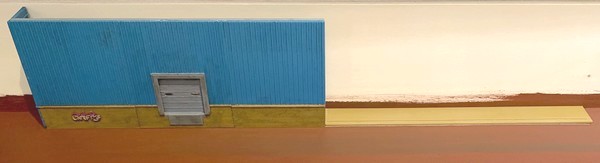

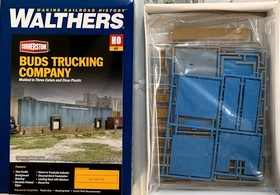

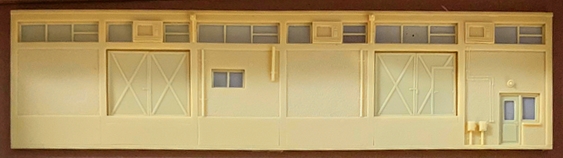

STRUCTURE #1:

THE WAREHOUSE

|

|

|

| |

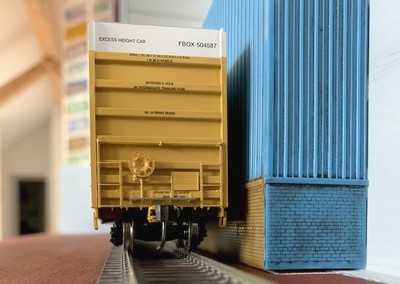

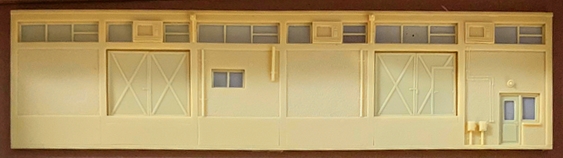

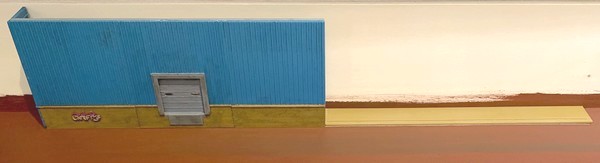

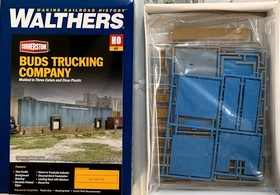

| Even though the restricted size

of the layout clearly limited the possibilities

for structures, I wanted the two tracks and the

shuffling of rolling stock to convey a certain

meaningfulness. Having a modern-style warehouse

as a backdrop and a "destination"

wasn't very orginial, but since I already had the

Walthers "thin profile background

building" (something I would call

"low-relief") it was both an easy and

convenient choice to make. At 1-1/8 inches

(2.25 cm) the structure has a very shallow

footprint, yet its length of 19 inches (48.3 cm)

and its heigth of 4 inches (10 cm) result in a

fairly sizeable building, making it all the more

ideal for Pecan Street.

|

|

|

|

| |

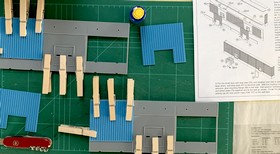

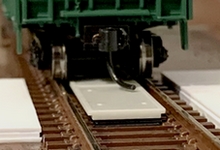

| Since clearances are all important (and especially so

if you only have 6 inches to work with), assembling the

warehouse was the first step needed to provide a point of

reference for where exactly the tracks could go. At the

same time, the baseboard sides were added, and then a

liberal coat of acrylic paint sealed the baseboard top -

track ballasting and scenicking involves no small amount

of a mix of water and glue to fix it all in place, and

baseboards that haven't been sealed this way may well

start to warp. |

| |

| The low-relief warehouse kit is a

very straightforward build, as was adding two

Walthers SceneMaster modern-style wall lamps

along with some initial weathering using Vallejo

grey and black wash.

Having a narrow gap

between rolling stock and the warehouse front not

only results in a more prototypical appearance,

it also provides more room to space out the two

tracks a bit, making operation easier.

It is important to be

very diligent in this step, using the widest and

tallest item of rolling stock along with all

locomotives intended for use on the layout, to

ensure none of them fouls the warehouse.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| With all the clearances worked

out and marked down, it was time to lay the track

- once I decided which track to use. Peco is my

track of choice (due to decades of trouble-free

running) but that still left me with two options

for an HO scale layout: regular code 100 or code

83 US style track.

While the code 100 track has a slightly

chunkier rail profile, the most noticeable

difference is the smaller size and closer spacing

of the ties, giving the code 83 version a

distinctly more authentic "American"

look.

So why even hesitate?

|

|

|

|

| |

| The sturdiness of Peco code 100

track is simply unsurpassed, and since Pecan Street would

require joining two segments every time it would be set

up (and then disconnecting those segments again for

storage), this seemed to be an aspect worth taking into

consideration. |

| |

|

|

Not that

Peco code 83 is overly delicate, but the finer

rail profile does make it feel somewhat less

bombproof in comparison. As an added bonus, using

code 100 track would allow me to fall back on a

short piece of Peco setrack - the ultimate means

of connecting the two segments in a sturdy and

reliable way. Code 100 track would also allow me

to run some older models with oversize wheel

flanges. As for

the visuals, I had looked into that a few years

prior (for a US layout that ultimately never

materialized) by setting down a 50' boxcar on the

code 100 track of my Little Bazeley Mk1 layout.

Not surprisingly, with no code 83 track right

next to it for direct comparison, the weathered

and ballasted code 100 track didn't look too bad,

in spite of the "wrong" size and

spacing of the ties.

|

|

| |

| Ultimately, my decision was helped by looking at

prototype railroad locations around warehouses - and

seeing a clear and distinct potential for hiding any

perceived visual shortcomings of code 100 rail, since the

tracks in those places often convey an entirely different

look than what can be seen on a through traffic line. |

| |

| Looking north from a road

crossing on Titan Row in Orlando FL in 2021, we

see two modern warehouse structures served by two

sidings, along with a line that runs on to serve

more customers. The track here is far from

being dilapidated, in fact the through track

seems to have been re-ballasted recently and ties

replaced. But ballast on industrial trackage

often doesn't get tamped and regulated the way it

would on busier stretches of railroad track.

As a result, ties often get covered by ballast

both to the sides of the rails as well as in

their center, and over time, grass and weeds will

grow up in places.

A dry run using a piece of Peco code 100 track

showed that emulating this appearance on Pecan

Street would minimize the visual impression of

the larger and more spaced out ties.

As a result, I opted for sturdiness and proven

trouble-free running qualities and chose Peco

code 100 track for the layout.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| The simple track

configuration involved in a "tuning fork"

layout was thus laid using Peco code 100 track; Streamline

flextrack for the siding in front of the warehouse (since

this curves away from the single switch on this segment),

and pieces of Setrack "snap track" for

the siding running along the front of the layout (simply

because I had quite a stash of this available, and it

does make putting down a segment of straight trackage a

breeze). |

| |

|

|

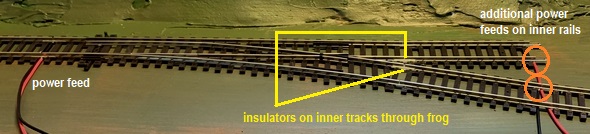

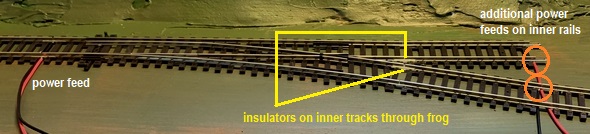

The switch is a Peco Streamline

medium radius "Insulfrog" point,

meaning it has an electrically insulated frog and

- unlike "Electrofrog" switches (that

have an electrically live frog) - requires no

extra wiring to operate, being DCC-friendly

straight out of the packaging.

The only snag

that "Insulfrog" points can throw up

with DCC operation is a potential shorting

problem with some metal wheels as they travel

through the frog. Even though this only seems to

be the case with a very limited number of

wheelsets, I decided to play it safe and add

insulator joiners to the inner rails past the

frog (as per the instructions printed on the Peco

packaging of the switch).

The illustration below is taken from my Little

Bazeley layout, but the principle remains the

same for any layout.

|

|

| |

| Once everything panned

out, the simple track configuration was laid down in

virtually no time at all. I like to make sure that the track is firmly and

securely attached to the baseboard (no roadbed needed for

industrial tracks) before weathering and ballasting,

which is why I use Marklin Z Scale track pins. Due to

their very small size these are very inconspicuous yet

still hold the track down perfectly well.

A test run then makes

sure that all electrical connections work properly.

|

| |

|

| |

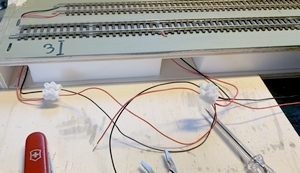

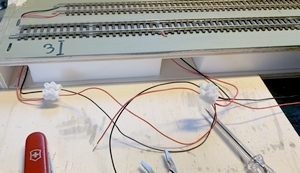

| There is also really

no difference in this case between an old-fashioned DC

wiring approach and a DCC friendly one. The only

difference are the additional feeder tracks

required due to the aforementioned insulator rail joiners

on the inner rails past the frog of the switch; I went

ahead and added additional feeders to both tracks at the

end of the two sidings to give this layout segment an

added boost in terms of feeding power to the track.

All

the wiring follows the common colour coding of

"black is at the back" (and therefore red wires

to the front rails).

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

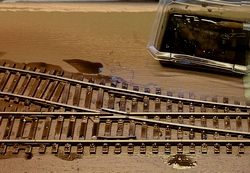

| As a first step in

weathering the tracks, I took the baseboard outside and

sprayed them a dark matt brown colour using an aerosol

spray can from the DIY store, masking parts of the switch

in order to avoid conductivity problems. |

| |

|

| |

| Like most modellers, I

have accumulated lots of "spare" items over the

years, and I felt that Pecan Street would be an excellent

opportunity to use items from this stash. |

| |

| However,

the rattle can that I still had left over from my

Little Bazeley Mk2 layout build a few months

back, proved to be a bad choice.

The spray paint went on

as usual and without any problems, but when I

tried to wipe the top of the rails immediately

after, I found that the paint was too sticky to

come off neatly - or even refused to do so at

all.

I suspect that

the aerosol/paint/solvent mix had deteriorated

inside the half-empty rattle can, but whatever

the exact reason, I had to apply a different

approach than I usually would. Deciding to let

the paint dry completely, I left it alone for a

good 48 hours. After this, I used swabs saturated

with isopropyl alcohol to wipe the top of the

rails clean.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

This

worked well (and without the damage abrasive

tools inflict on the rail surfaces), although the

paint was a bit more stubborn in some places,

requiring two or even three swipes. In the end, however,

this unexpected problem was solved and all the

rails had a shiny surface (necessary to provide

good electrical pickup). The masked-off section

at the switch was then touched up with a fine

brush and rust-coloured acrylic paint.

In order to

brake up the unrealistic uniformity of the

colour, I then added a few touches of RailMatch's

"sleeper grime" (an acrylic paint) as

well as some Vallejo grey and black washes

to the sleepers.

Even though

this is a very straightforward and simple way to

achieve a more realistic look, some (if not most

of it) would ultimately be lost - since I was

planning to "sink" the track and ties

well into the ballast. However, weathering the

track really is an essential part of recreating

the atmosphere of the real railroads, so I just

went ahead with it regardless.

More test

running and checking of all electrical

connections after this stage is essential to

discovering (and if needed ironing out) any bugs.

Once the functional aspects of the track are all

settled, it's time to add ballast to the

weathered track.

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Having ballasted model

track for a good thirty years in HO/OO, N and Z scale, I

felt confident that my array of proven methods

accumulated over that period of time would provide me

with a trouble-free part of putting together Pecan Street

- especially since for the first time I would not be

attempting to produce a well-maintained and neat looking

section of ballasted tracks. I was in for something of a

surprise - and an extended episode of accidental

modelling. Initially though, everything went according to

plan.

|

| |

Track

maintenance work at Abingdon Va, 15

October 2018 (Video)

|

|

The colour of ballast varies

greatly on the prototype, depending on

the type of stone used and how much soil

and rust is deposited on the trackbed by

traffic on the line. A little bit of

research into the area and era modelled

(on location if possible, otherwise

online and through books and other media)

really helps to get it right. Unless you are

basing your layout on a specific location

with its own unique characteristics,

railroad sidings serving warehouses in

the US commonly seem to use grey, light

grey or buff coloured ballast.

I have

been using Woodland Scenics ballast

(actually made from crushed walnut

shells) for decades and saw no reason to

change that.

|

|

|

| |

| For this layout, I

opted for my favourite, the "fine" grade light

grey ballast (B74), which is usually marketed for N scale

and looks really good on HO track. With Pecan

Street, however, one

fundamental aspect of ballasting was different. |

| |

| Usually

(i.e. on all my previous layouts) I would try to

achieve a fairly neat appearance where the

ballast was evenly spread, with no loose

particles on top of the ties or clinging to the

rails. I would achieve this by sprinkling on only

small quantities from a teaspoon and then

straightening the ballast out using my index

finger, a fine paint brush, and a toothpick.

The basic idea is that

you can always go back for seconds and don't want

to use too much at once in order to avoid a mess.

It's also at this point that your Peco code 100

track (dismissed as "toylike" by some

modellers) really starts to shine.

|

|

|

|

| |

| This time, though,

that "mess" which I would always try to avoid

was exactly what I now wanted for Pecan Street. |

| |

|

|

What

I didn't bank on was that I would find myself in

a little bit of a mess of a different kind. In spite of not having

to worry about not getting ballast everywhere, I

still tried to apply some amount of restraint.

Once I was

happy with the general look, I proceeded to

permanently glue the ballast down.

For decades I

have done this using what most modellers use: a

mix of water and white glue (approximately at a

1:1 ratio) with a drop of washing up liquid (to

break surface tension).

|

|

|

|

| |

| The mix is then carefully applied from a dropper,

which proved a better choice here than a syringe (both came from the vet). The

idea is to really soak the ballast, as this ensures that

the water/glue mix doesn't just cover the surface. Mixing white glue and water in this way

is a time-tested method for ballasting track, and once

applied it's best to leave everything to dry thoroughly

for at least 24 hours. |

| |

|

|

And this is

when things started to behave quite unlike what I

was expecting from my past experience. To kick things off, I found that

the white glue I was using dried perfectly clear,

but with a distinct and very glossy shine. While

this would be great if you modelled a scene

during or after a rainfall, it was not what I

wanted.

Maybe it was just that

make of white glue. Common modeller's wisdom has

it that the cheapest white glue you can get is

the best for this, but after testing out an

additional two or three brands I found that none

of them really dried with a matte appearance.

|

|

| |

| I noticed that all the

labels only specified that the glue would dry clear but

made no reference to a glossy or matte appearance. |

| |

| On top of this, I then noted a

second, completely unexpected problem with the

stretch of track that I had already ballasted. Even though I didn't

just throw down the ballast with wild abandon, I

found that after I had soaked the mix of Woodland

Scenics ballast and scenic scatter material

(still using the "trusted" mix of white

glue, water and a drop of dishwasher detergent),

it had a light but still distinct tendency of

expanding compared to what it looked like in its

dry condition.

The result was

a bit more "ballast and weed cover"

than I had aimed for. While the visuals were

fine, I found that running a "test car"

(in the form of a Walthers boxcar) over the newly

ballasted track did reveal two or three spots

where the ballast interfered with the wheel

flanges.

It wasn't that big a deal and easily rectified

by scraping away the few grains of ballast

causing the problem. Any small screwdriver or

similar tool will do the job.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

In this case, however, I used a

cheap calculus scaler (I got mine on eBay) that

makes access easy and allows for a pin-pointed

removal of stray ballast. |

|

| |

| I was starting to realize that, contrary to

my initial assumption, covering ties in ballast

was actually more challenging than creating a

clean and neat spread of ballast around the rails

and ties. |

|

| |

| So

I made a point from this moment on of putting

down less ballast than originally intended,

especially between the rails.

This would make sure

there would be no problems with wheel flanges,

and potentially "underdone" spots could

always be touched up later.

|

|

|

|

| |

| This did not, however,

fix the "white glue glossy finish" problem. Was

it possible that the formula for white glue had changed

across the board? Whatever the reason, I quite

unexpectedly found myself having to look for an

alternative solution. There were several options, but I

wanted something that wouldn't be too far removed from

what I had been using previously. And so I found myself

purchasing a container of Woodland Scenics Scenic

Cement™. |

| |

|

| |

| It solved my problem instantly, drying to a clear

matte finish and not "pushing up" the ballast.

For whatever reason (and it can't be too sophisticated),

this scenic cement worked while my trusted home-made mix

didn't. Of course there can't be too much of a difference

in terms of components (the scenic cement incorporates a

whetting agent, too) but since it worked and I wasn't

going to be needing gallons of it, that was all fine by

me. Sometimes there's nothing else to do but embrace

accidental modelling when it happens. From here on out, I

will be using Scenic Cement. Something I never do,

though, inspite of many positive reports from other

modellers, is "mist" the ballast with isopropyl

alcohol (IPA) before applying the water/glue mix. Even

when using a perfume atomizer, I have found that no

matter the distance from which the IPA is sprayed on it

tends to disturb the dry ballast - which is the exact

opposite of what this procedure is supposed to achieve.

|

| |

|

|

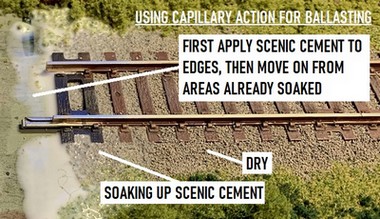

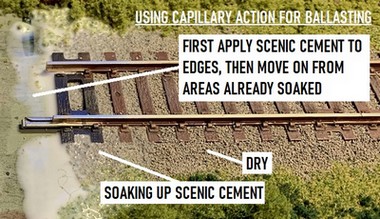

So instead of any

"pre-treatment", I simply apply the

scenic cement (or, previously, water/glue mix) by

taking advantage of its capillary force.

Because the scenic glue has a lower surface

tension than the ballast and scenic material

(thanks to the "wetting" agent),

applying the mix close to the edge of the ballast

(area #1 in the picture) results in the watered

down glue being drawn in and seeping into the dry

ballast by itself - or rather by its capillary

force (2).

Ultimately the effect is similar to blotting

paper or household tissues sucking up liquids,

and it leaves the ballast almost completely

undisturbed (3). The illustration used here shows

a piece of Z scale track, but the principle

obviously applies regardless of scale.

|

|

| |

| Letting the capillary force do its magic does however

result in a slightly slower procedure. Starting at the

edges of the area to be treated, patience is required to

then let the scenic cement work its way properly into the

ballast and scenic material (which might take a minute or

two). Additional scenic cement is then only applied to

the areas which have already soaked up the mix,

saturating them to the point where the mix then seeps

into the adjoining area of dry ballast and scatter

material. It is definitely a patience game, but then

ballasting shouldn't be rushed anyway. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

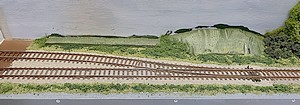

| Since ballasting is best done in stages over several

days, I felt this was a good point in time to assemble

the second baseboard in-between ballasting sessions. It's

an almost identical twin, constructed using the same

methods a baseboard #1, except that I opted for one less

piece of styrofoam. Having six of those instead of seven

would give me more wiggle-room to run the wiring. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

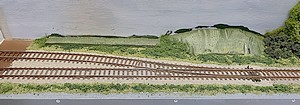

| |

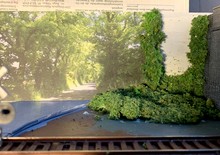

| Pecan Street obviously doesn't allow for a lot of

scenery, but what little could be done on segment #1

would be situated towards the backscene and fulfill two

purposes: convey an atmosphere of a more rural than urban

setting, and hide the fact that the warehouse is nothing

more than a flat frontage essentially just stuck right

onto the backdrop. Taken together, those two points

would ideally result in a number of trees, but the layout

simply doesn't allow for that, so it would essentially

have to be shrubbery and possibly something akin to

low-relief trees. It is this kind of challenge that fuels

my appreciation of theatrical

layout design, since art directors in the

entertainment business often have to work with similarly

restricted spaces, be it on a theatrical or a movie

production stage.

|

| |

|

| |

| Since the shrubbery will be "growing" up

from the baseboard top to the backdrop, providing a base

which provides an additional vertical structural support

will make it easier to bring the shrubbery up higher so

the required effect will actually work. This base is

made up from four pieces of narrow styrofoam. They are

shaped to provide a slope and then covered in a very

thick layer of green acrylic paint - normally I would

cover the styrofoam with a layer of plaster of Paris but

this seemed like overkill in this situation. When all

will be done, nothing of that slope should remain

visible. The next steps on this will, however, only be

tackled once all the ballasting in that area is done.

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| Following the "heavy ballasting" around the

sidings, the area around the switch was ballasted with a

decisively lighter touch (and therefore more in line with

what I was used to from previous layouts). The idea here

is that the track is in the process of being somewhat

rehabilitated, as the tamped ballast along with a small

pile of fresh ballast besides the switch is supposed to

indicate. At a later point, the two slabs in the

background will support a few lengths of switched-out

worn and rusty rails. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

| The narrow strip at

the back of the left-hand section of Pecan Street doesn't

allow for much in terms of scenery. The up side of this

is that a lot less scenic material is needed compared to

what would usually be the case. The possible down side:

the scenery needs to be carefully compressed in order to

look convincing. |

| |

| I

have always built up my layout scenery in layers.

This allows for a gradual build-up and blending,

which avoids an overly uniform look and also

makes tweaking things a lot easier. The first stage in

building up the background scenery to the side of

the warehouse was to cover the styrofoam base

with white glue; this serves as a base for a

generously applied mix of Woodland Scenics

"fine turf", mixing "green

grass" (T45, light to medium green) and

"weeds" (T46, medium to dark green).

This produces a

slope covered in low grass of various shades of

colour. It provides a pleasing enough look, but

more vegetation is clearly needed. Adding

different colour shades of Woodland Scenics

"bushes" (FC146 medium green, FC147

dark green, and FC149 forest blend) results in

another layer, and a more interestingly varied

backdrop scenery.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Having more dark colours towards the very back helps

to accentuate the perception of visual depth. For the

most part, this second layer is sufficient, since the

background scenery is supposed to be just that: its role

is not to attract attention but rather quite the opposite

- to just blend in with the backdrop (which, being of a

deliberately toned down "not so sunny sky"

tone, also doesn't detract from what is going on in the

foreground). |

| |

|

|

Using

low-relief buildings imitates a stage trick and

is a prime example of theatrical

layout design. But in order for this

visual deception to work, it is important to

disguise the true dimensions of such "stage

props" - the unhindered view of the shallow

sidewalls of the warehouse meeting up with the

backdrop is a dead giveaway at first sight.

The deception works as soon as that view is

obstructed, preventing a clear visual perception

of where exactly the warehouse ends and the

backdrop begins.

This is what stage designers do both in

theatres and on film production sets, and in this

case the effect is easily accomplished by adding

some sprawling vegetation in the form of trees

and tall bushes.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| This sprawling vegetation is essentially a first

layer; refinements can be made anytime at a later stage.

It is formed of Woodland Scenics "bushes" (again mixing FC146 medium

green, FC147 dark green, and FC149 forest blend)

and "foliage" made up of various colours (F51

light green, F52 medium green, and F53 dark green). |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| |

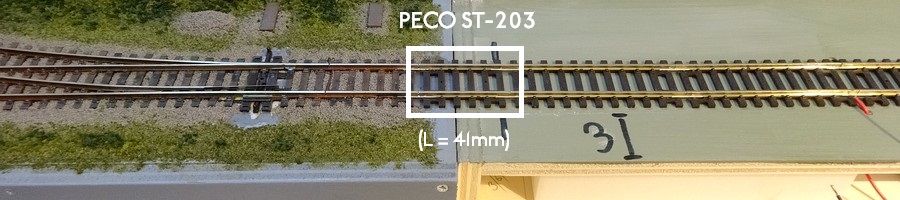

| With the left hand segment of the layout having come

along quite a bit, work started shifting to the right

hand segment - and with it the question of how the two

segments would ultimately be joined up for operating

sessions. Although actually, that question had been

answered long before, since the possibilities of joining

up the two segments with a piece of setrack was an

important point in going for Peco code 100 track. |

| |

| Previous experience with modules has lead me to trade

visuals for truly secure physical and electrical track

connections across segments, and nothing beats having a

short piece of track as a "bridging" element. |

| |

|

| |

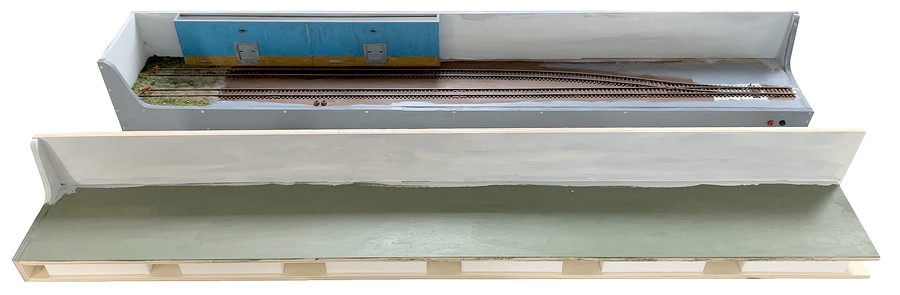

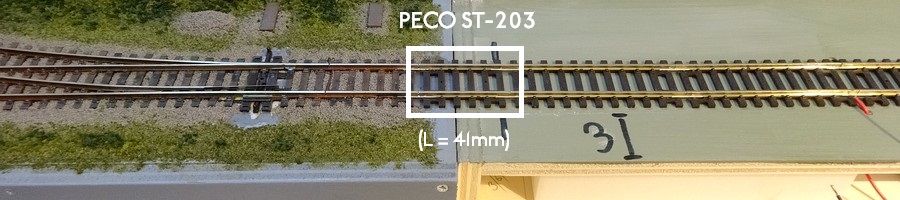

| The two segments of Pecan Street are joined up by a

very short (41mm) piece of track from the Peco setrack

range - a sturdy and reliable connection. The tracks on

both segments have been set back accordingly in order to

allow for a snug fit. Once both segments are fully

scenicked, the "connector track" can be

weathered in order to tone down the visuals. |

| |

| |

|

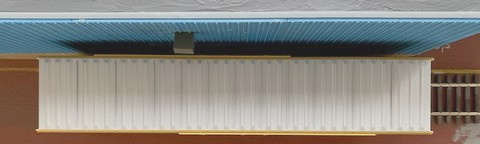

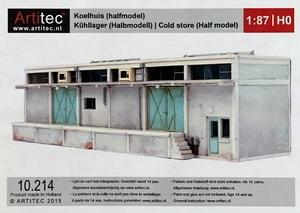

STRUCTURE #2:

THE COLD STORAGE

|

|

|

| |

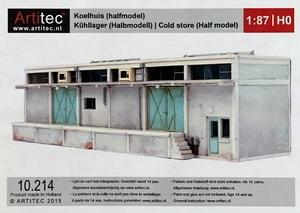

| A true "tuning fork" layout only has a

single lead track running up to the point, but early on

in my planning I decided to add some additional visual

interest and operational potential by adding another

point on the lead track with a very short spur that would

hold one single piece of rolling stock only. In order

to give that single car spot some sense of being another

place that would have the odd boxcar or mechanical reefer

dropped off and picked up, I decided to go for the Dutch

company Artitec's low-relief kit of a cold storage

building that I had bought years ago (and is no longer

produced).

|

| |

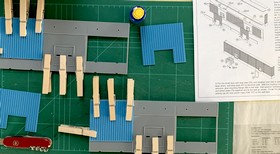

| The kit is interesting in that it

is made from resin rather than plastic; this

allows for larger pieces with details moulded on.

|

|

|

|

| |

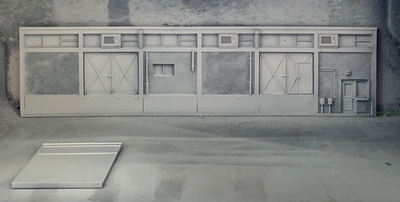

| As a result, the entire model is made up of only a

handful of parts. Somewhat inspired by the rendition on

the box, I gave the few parts of the kit I would

ultimately be needing two coats of paint from a rattle

can - the first black (for contrast and texture), the

second a light spray of white. |

| |

|

|

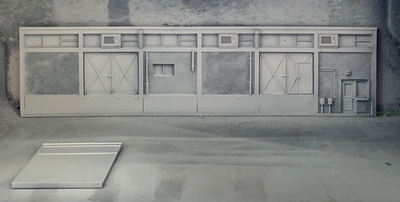

The

transformation from the original light yellow

colour is quite striking, and the rather finely

moulded details are nicely highlighted by the

darker shades from the first coat of spray paint. As straightforward as this model

is, it would need some adapting to fit the

reduced footprint available on the narrow layout.

First off, the already

low-relief model was reduced further in depth

from the original 5cm to just a tad over 2cm,

resulting in a setup almost identical to the

warehouse scene on the left hand segment.

To give the model a bit

more stability I cut a 2cm thick piece of

styrofoam to shape and glued it to the back of

the building's front

|

|

| |

| Since the roof moulding didn't

really work with the reduced depth of the model, I

replaced it with a simple piece of styrene and then added

the moulded loading platform and canopy as per the

instructions. |

| |

|

| |

| As

with the warehouse on the left hand segment,

getting the clearances right with this building

is the first step as these determine where

exactly the rails will go. And again the object was

to get cars fairly close up to the loading dock

edge, as this will eventually make things look a

lot more realistic.

Once the

measurements were all in, checked, and then

double and triple checked, laying the track was

next.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

MORE TRACKLAYING

& WIRING

|

|

|

| |

| Following the same procedure for laying track and

wiring it all up as on the first, left hand side segment,

the simple track configuration (which is indeed identical

to the one on the left hand segment) was again made up of

Peco code 100 track Streamline

flextrack for the siding in front of the cold storage

building and pieces of Setrack "snap

track" for the siding running along the front of the

layout. |

| |

|

| |

No changes to the switch arrangement

either, using

a Peco Streamline

medium radius "Insulfrog" point

and

adding insulator joiners to the inner rails past the frog

and extra wire feeds to all three segments of track, as

per Peco's instructions printed on the packaging of the

switch.

|

| |

|

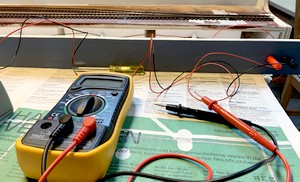

|

And again, Marklin Z Scale track

pins were used to attach the track firmly and

securely to the baseboard. Wiring such a simple

track configuration throws up no difference

between an old-fashioned DC wiring approach and a

DCC friendly one - although one could argue that

the way I brought together all three pairs of

feeder wires has a distinctly "old

school" look to it.

After the all important testing using a volt

meter to make sure that all connections work

properly and provide eletric current to all

segments of the track, weathering is next.

|

|

| |

|

BACK

TO WEATHERING THE TRACK

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| Avoiding the mistake of using the

contents of an old rattle can, I spraypainted the

rails, masking off (again, as always) the part of

the point which is made up of moveable parts and

also ensures connectivity for the elctrical

current. Painting the rails outside on a hot

August afternoon in the midst of the 2022

heatwave made the paint dry really quickly, so

that it was impossible to wipe and clean all the

rail surfaces before the paint started to set.

But based on the experience with the left hand

segment, I knew not to worry and just let the

remaining paint dry properly. A day later I used swabs saturated

with isopropyl alcohol to wipe the top of the

rails clean.

In order to

brake up the unrealistic uniformity of the

colour, I also repeated the process of darkening

the ties, except this time I only used a

generous splash of Vallejo black wash (which,

when dry, is quite transparent).

Once all is set

for the moment, making sure all electrical

connections still work as they are supposed to is

certainly a good idea before moving on to the

next steps.

|

|

|

|

| |

| I did this following

my usual best practice (applying current from a standard

1980s DC controller and measuring the current in all

relevant places with a volt meter) but then also got out

my old Roco/Atlas GP40 from 1984 for some actual test

running - just a simple moment of inspirational nostalgia. |

| |

|

| |

| |

|

|

| |

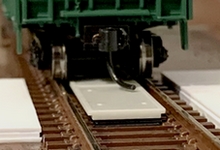

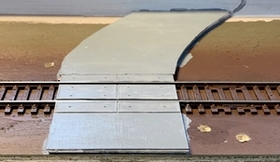

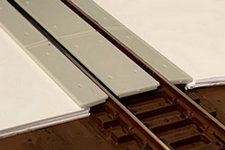

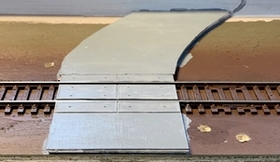

| Prior to ballasting a few scenic items needed to be

put in place, and one of them was a grade crossing. Apart from providing an opportunity to

add some scenic interest, the crossing was intended right

from the start to mark a boundary for switching moves

when operating Pecan Street in "tuning fork

switching puzzle" mode. |

| |

In essence, it

simply limits the length of a train (and

therefore the number of cars that can be switched

in one move) by having a rule in place which

states that the grade crossing cannot be blocked

during switching.

|

|

|

|

| |

| For this layout, I made a point of using as many

items as possible that I already had (i.e. purchased at

one time "for later"), and in my stash I found

a number of concrete grade crossing panels from BLMA

(since taken over by Atlas). |

| |

|

|

The nice thing about these was

that they not only fitted my very approximative

era very well (they have been used since the

1980s), but also happened to be the same type I

observed in April 2022, at a crossing over a

single Norfolk Southern track at Memorial

Hospital in Roanoke Va. The BLMA model consists

of two center panels and four side panels, but

given the restricted space I opted to use only

half of these components - which I would clearly

have to raise a bit since the packaging stated

that they would work from code 60 upwards.

|

|

| |

| The short stretch of road was built up around the

track using styrene sheets cut to shape, and the BLMA

panels brought closer to railhead level using styrene

shims. This is one of those occasions where a delicate

balance needs to be struck - setting the panel in between

the tracks too low will look terrible, setting it too

high will foul the couplers. As always with clearances,

it is best to use actual stock to make sure things fit;

in this case the central panel sits at a visually

realistic level - close, but not too close, for couplers

to clear it and run over it safely. |

| |

|

| |

|

|

The crossing will be guarded by a

pair of signals with working lights, using a very

nice brass item bought on eBay. Holes to

accomodate the signals are drilled, and the road

is given a coat of medium-light grey; this will

serve as the basis for some overall as well as

detail weathering later on.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

THE

END (A.K.A. CONNECTION TO

THE REST OF THE WORLD)

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

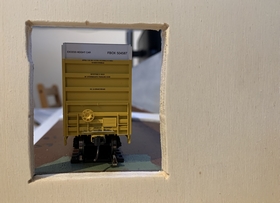

| In essence, Pecan Street is a self-contained layout.

And whilst there are no plans to add any extension (such

as connecting it to more modules) for the foreseeable

future, adding the possibility to do so at this stage

makes sense. |

| |

|

|

This also makes sense since there

is very little additional work involved in simply

cutting an opening into the sideframe (once again

making sure that the tallest and widest item of

rolling stock in use will pass through without

problems). On the layout itself, a scenic break

is needed to disguise the actual end of the track

regardless of whether it can be extended beyond

the baseboard frame or not.

|

|

|

|

| |

| A chance discovery of a 2022 model of a low relief

bridge from the Bachmann (UK) range of

"Scenecraft" resin models provided just the

kind of "scenic disguise" I was looking for.

Although intended for British layouts, the design seemed

a good fit for a layout based on an East Coast location. |

| |

|

|

In order to work visually the

depth of this very low relief model had to be

increased quite a bit. This was achieved by

adding a structure made up of three pieces of

styrofoam cut to size. The result in itself is a

very crude contraption, but since the model

covers it up, this is all it takes.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Black colour on the inside disguises the styrofoam

and creates enough of a "dark passageway" feel

to make it work as a scenic break - one of many

techniques I like to use that originally stem from theatrical

stage design. For the moment, that was it; the

obvious rough bits and edges would be patched up and

hidden in scenery after the adjacent scene of the track

crossing had been worked on. |

| |

| |

|

STAGE

TRICK: THE CROSSING

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| The narrow nature of Pecan Street poses a number of

challenges, some of which have already been mentioned.

Most of those boil down to the fact that there simply

isn't a lot of room for scenery - and the grade crossing

is certainly one of the areas on the layout where this is

felt the most. I have also mentioned how, in such

cases, I like to fall back on Frank Ellison's modelling

approach involving theatrical

stage design - and this is perhaps also most apparent

in how the grade crossing is set up on Pecan Street.

|

| |

| In its raw modelling state, the

road crossing the tracks curves away slightly in

order to provide at least some illusion that it

doesn't just hit the backdrop in a head-on

collision, but it still clearly ends right there,

a mere 3.5 inches (9 cm) away from the track. In

order to conceal this, a number of steps would be

necessary to create an illusion of depth, and one

central prop was a rather nice model of a truck,

manufactured by a company named Boley, that I had

bought cheaply and put aside years ago for

"some future project". Now, it would

literally take center stage.

|

|

|

|

| |

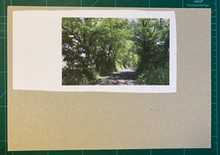

| But before that could happen, the stage itself had to

be set. The idea was to add a flat photographic backscene

to the backdrop, and then add some semi-relief props to

make the scene look threedimensional and create the

impression that the road crossing the tracks actually

went somewhere in the background. After finding a

suitable royalty-free image on the web, this was reduced

to the required size, cut out and glued onto sturdy 2mm

cardboard, and given a protective layer of matt varnish.

This was then in turn glued to the backdrop, and a first

batch of scenic material applied to cover both the edge

of the card and fill in a gap between the overbridge and

the backdrop. For the more three-dimensional props, two

large scenic trees were cut in half and then glued into

place.

|

| |

|

| The trees

came from a range that can generally be

termed "cheap model trees from China

sold on eBay". They are somewhat

infamous for their overall identical

appearance (which of course explains the

cheap price) but also rather popular,

since it is fairly easy to improve their

looks. Usually the excuse for giving

these a go is the sheer number of trees

needed and the cost involved, but I still

happened to have these lying around after

a curiosity purchase and successfully (I

felt) "pimping" them with

Woodland Scenics foliage for use on Little

Bazeley.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

Building up more layers of

scenery (mixing Woodland Scenics fine and coarse

turf, foliage and bushes of various colour

shades) allows the foreground to blend with the

flat backscene, further enhanced by some

strategic "shadows". As on a theatrical

stage, it is all aimed at deceiving the onlooker

into believing that the scene has more depth and

reaches further back than it actually does. The

scene could be left this way, but in order to

fool even a lingering observer a bit longer, the

aforementioned truck is placed as a view block

which also deflects attention from the flat

backdrop to an actual three-dimensional prop in

the foreground.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| In order to achieve this illusion, some further

theatrical trickery is necessary - what seems to be a

truck is actually only part of one. Cutting down the

rear of the vehicule at a 45º angle not only allows a

longer vehicule to be squeezed into what little space

there is, it can then also be placed in a skewed position

(another theatrical trick for props that are supposed to

fool our sense of perspective).

|

| |

|

| Taking apart the truck for the

procedure was also a good opportunity to fit a

driver behind its wheel - a suitably cut-up

Preise figure from a set of track maintenance

workers. It's another stage setting adage: things

that are there may not always get noticed, but

things that are missing most certainly will. In

a perfect world, I would have turned the front

wheels somewhat, but simply thought of this too

late - so I simply imagine the driver is just

about to apply the steering wheel...

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

BACK

TO BALLASTING &

SCENERY

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| With the crossing scene set up, the rest of the

remaining portion of the second, right-hand segment, was

to be given a fairly straightforward treatment in terms

of ballasting and background scenery. |

| |

|

|

So out came my array of

transparent household storage boxes, holding the

contents of various bags of ballast and scenic

material (mostly from the Woodland Scenics

range). The usual pieces of styorofoam were

cut, glued down and given a heavy coat of dull

green acrylic paint in order to serve as contours

for the background scenicking in front of the

backdrop.

As for the ballasting I decided to generally

keep it fairly neat on this part of the layout

compared to the warehouse segment. The basic plan

was to see how things would look once completed

that way, and then add more ballast or weeds on

top of the already ballasted track if needed.

|

|

| |

|

| |

| Once tamped down this

way, more ballast can be added where needed (which is a

lot easier than getting rid of too much ballast). It is

impossible to avoid getting at least a little bit of

ballast where it shouldn't be (e.g.on the sides of the

rail), but all it takes to remove this is a gentle

approach using a fine brush and a toothpick along with

some patience. |

| |

| Once

everything looks okay, scenic cement is applied

from a dropper to the edges of the ballasted

area, letting the ballast and scenic material

soak it up thanks to capillary action. Adding

more scenic cement to areas already soaked in it

will make it "spread" to areas that are

still dry. Again, some patience is required, but it

doesn't take too long and causes minimal

disturbance to the unsecured ballast grains (glue

applied directly to dry ballast will cause it to

float and drift around). Since taking advantage

of capillary action for ballasting, I have in

essence switched from using a syringe to a simple

drop dispenser with a rubber teat, since the

latter provides a more controlled and gentle

application.

|

|

|

|

| |

| Again, the scenic ground cover is built up in steps by first covering the

painted styrofoam bases with white glue, which in turn is

covered with a mix of Woodland Scenics "fine turf

green grass" (T45, light to medium green) and

"weeds" (T46, medium to dark green) in order to

avoid a uniform look. Adding different colour shades of

Woodland Scenics "bushes" (FC146 medium green,

FC147 dark green, and FC149 forest blend) then results in

another layer, which is secured with scenic cement. |

| |

|

|

In order to provide a smooth

transition to the road crossing scene, a short

tree line needs to be built up along this basic

scenery - which means more tweaking and pruning

of some "cheap model trees from China sold

on eBay". |

|

| |

| Since this is strictly background scenery and

therefore explicitly not supposed to attract attention

away from the foreground, it's not about detail but

rather the overall impression. |

| |

| Tree stems

therefore do not need to be visible, even

more so since the trees are heavy and

dense in foliage (a real life example of

such a tree would be the Arborvitae

Tree). This in turn means that I really

cut into the "plastic skeleton"

of these trees, leaving only a minimal

number of unconnected

"branches" - they won't be

visible, but this provides just the right

amount of structural cohesion and

flexibility at the same time. The cut-up

structure of the tree still shows off

some of the very bright green the tree

originally comes in, but once it's all

turned around the Woodland Scenics

foliage hides practically all of that.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

| |

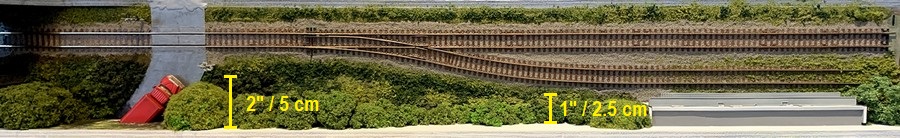

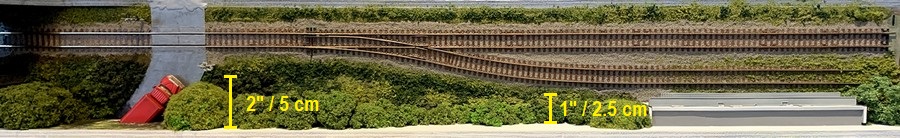

| Since the layout itself only has a very shallow depth

of 6 inches (15 cm), the background scenery needs to be

extremely compressed. It would be almost impossible to

fit an actual complete model of a tree into a space of 2

inches (along the single track), let alone into the

cramped quarters of just one inch (along the segment with

the mainline and the spur). Cutting up the trees is

therefore very much the equivalent of having

super-low-relief structures (as, indeed, the storage

building on the spur is). |

| |

|

| |

| This also means that the tree line needs to be dense;

too much light foliage which would allow the onlooker to

see through the trees would be a dead giveaway. Stage

designers have developed many different tools to creating

the illusion that a scene is much deeper than it actually

is, and this is just one example of how applying theatrical

stage design to a layout works. Another trick of the

trade applies to hiding the true dimensions of low-relief

buildings. As with the warehouse on the left-hand

segment, an unobstructed view of the storage building on

this segment will clearly show that the side walls are

very shallow since they meet up with the backdrop almost

immediately.

In order to create the illusion of an actual building

that reaches further into the background (as a real

structure would) the view of the side wall needs to be

obstructed, This is exactly what stage designers do both

in theatres and on film production sets, and in this case

the effect is easily accomplished by again adding some

sprawling vegetation. On the more visible right hand side

of the building the tree line meets up with it, along

with some shrubs and bushes. For the left hand side of

the building - which is in the far left corner of this

segment and thus less open visually - I opted for a more

refinde model of an individual tree.

|

| |

|

| |

| Unlike the cheap quantity-over-quality plastic

examples from China, this one was hand-made in Vietnam

using strands of wire to simulate the bark and branches

more realistically (as is the foliage). Also available on

eBay, these trees are of a far superior quality, but

obviously also carry a higher price tag (you get what you

pay for). The corner seemed a good spot to

"plant" such a model - visible enough, but not

too much. The tree is used as is, with no cutting, and it

does protrude slightly out into the spur a bit, but since

its location is the end of the line for that siding, this

isn't a problem. |

| |

| Building up

the scenery in layers like this also has

the distinct advantage that it's always

possible to go back and add more shrubs,

bushes, weeds and other items later on. But

already at this point, the background

scenery fulfills its purpose. It provides

a setting, disguises the otherwise

obvious spatial limits of the layout, and

overall sets the mood of the scene. And

of course it works best when there's

something in the foreground that shifts

the focus of attention.

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Work in progress, more

to come...

|

| |

| |

| |

|

| |

Text and

pictures are (c) 2022-2024 Adrian Wymann.

|

| |

page created 12 March 2022

last updated 21 June 2024

|

|

| |